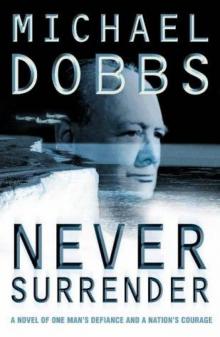

WC02 - Never Surrender

Michael Dobbs

NEVER SURRENDER

Michael Dobbs

Synopsis

The extraordinary new novel from the best selling author of Winston's War finds Churchill at his lowest ebb pitted in personal confrontation with Adolf Hitler, and with ghosts from his tormented past.

Friday 10 May 1940. Hitler launches a devastating attack that within days will overrun France, Holland and Belgium, and bring Britain to its knees at Dunkirk. It is also the day Winston Churchill becomes Prime Minister. He is the one man capable of standing in Hitler's way -yet Churchill is still deeply mistrusted within his own Cabinet and haunted by the memory of his tortured father.

Never Surrender's a novel about the courage and defiance that were displayed in abundance -not just by Churchill, but by ordinary men and women over three of the most momentous weeks in British history. At the end, Hitler stood at the gates of Paris and was master of all he surveyed. But Churchill had already broken him on the most crucial battlefield of all, the battlefield of the mind.

"Dobbs is an author who can bring historical happenings so vitally back to life ... made all the more impressive by being, so far as I could see, historically accurate in every respect." Anthony Howard, The Times on Winston's War

About the Author

Michael Dobbs' books make an impact, not simply because they are superbly written but also because they have an uncanny knack of being totally timely. His award-winning House of Cards trilogy foreshadowed both the downfall of Margaret Thatcher and the increasing turmoil within the Royal Family, while his Goodfellowe MP novels showed how a small band of highly motivated men could bring a great city to its knees. His most recent best selling novel, Winston's War, was published just as the nation was voting for Winston Churchill as the Greatest Briton.

He has been an academic, a broadcaster, a senior corporate executive and an adviser to two Prime Ministers. He was at Margaret Thatcher's side when she walked into Downing Street, and with John Major when he was kicked out. As The Times has said, 'he certainly knows where all the skeletons are hidden'. He has also, perhaps less kindly, been described as "Westminster's baby-faced hit man' and 'a man who, in Latin America, would have been shot."

He tries to live quietly in Wiltshire.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am often asked about the difference between history and drama, as though there is some clear dividing line. There is not. Written history is inevitably only a fragment of any story and can never be complete, and it's surprising how many histories contain desperate errors of omission or simple errors of fact. As I have mentioned in the Epilogue, even Churchill's own version of history could at times be outrageously loose.

Even those histories that are constructed as tightly as possible around 'the facts' still leave room for the sort of speculation about motives and emotions that are such an important component in trying to understand not only what happened, but why something happened.

I'm not trying to pretend that Never Surrender is in some way 'the truth'. It is a work of fiction and I have taken all the dramatic liberties required to construct what I hope is an enjoyable read. However, within those constraints I have struggled hard to stay as close as I could to the established events of the time as I understand them. My hope is that this may help readers understand the events of those few tumultuous weeks a little better, and remind them that behind every great event there is usually a man or a woman who is going through some sort of personal crisis. Many readers of Winston's War have told me that the novel encouraged them to read more deeply through the histories of that period in order to make up their own minds about the personalities and events. If Never Surrender has the same result, I couldn't be happier.

I suppose this is a convoluted way of getting round to thanking those who have helped me, while at the same time excusing them from any liability for the result. So I shall start by thanking Mrs. Joanna Grant Peterkin, the headmistress of St. George's School, Ascot, and her staff who so kindly allowed me to trawl through their archives and wander around Churchill's first school. I'm delighted to say that the school has changed beyond recognition since his time, and the happy and welcoming atmosphere the modern visitor encounters bears no resemblance to the harsh Victorian realities of young Winston's day. I am also indebted to two old friends, the Reverend Robert Webb (himself one of my earliest teachers) and the Reverend David Henderson, both of whom gave me much food for thought while I was constructing the character of Henry Chichester. Whatever limited success I've had in depicting his road to salvation is largely due to them. David Jolliffe, who was until recently Director General Army Medical Services, kindly gave me an introduction to the Army Medical Services Museum at Keogh Barracks and also the Royal Logistic Corps Museum at Deepcut, both of which gave of their time and expertise most freely, while Dr. Robert Lefever as always has illuminated the darkness surrounding the various medical mysteries I continue to stumble across. I am also grateful to The Random House Group Ltd for permission to reprint extracts from This Is Berlin by William L. Shirer, published by Hutchinson/ Arrow

It would perhaps seem strange and even a little pretentious to offer a full bibliography of the books I have consulted in preparing a novel, but three in particular I found inspirational and commend to anyone wishing to dig a little deeper. The first is Five Days in London, written by John Lukacs, who was an old colleague of mine from my days as a doctoral student in America; the second is Defying Hitler by Sebastian Haffner. The final book I wish to mention is entitled Flames of Calais, written by Airey Neave. The story of the defenders of Calais has been overwhelmed by the events that took place in and around Dunkirk a few days later, and I was spellbound to read Airey's account. He was captured at Calais, escaped from the notorious prisoner-of-war camp at Colditz Castle, was one of the prosecution team at the Nuremberg Trials and eventually became a senior Member of Parliament who masterminded Margaret Thatcher's successful campaign for the leadership of the Conservative Party. That was when I first knew him. I remember an afternoon in early 1979 when I sat with him on a sofa and listened to him talk about his many plans for the future. The following day he was murdered by the IRA. Until I read his book on Calais, I never realized quite what an extraordinary man he was.

And, finally, I must thank the boys William, Michael, Alexander and Harry. They sat patiently, and usually noiselessly, outside my door during the intensive months spent writing this book. When I heard any sound at all, it was usually their laughter. It made it all worthwhile.

MICHAEL DOBBS Hanging Langford, July 2003.

By Michael Dobbs

Winston Churchill novels

WINSTON'S WAR NEVER SURRENDER

The Tom Goodfellowe series

GOODFELLOWE MP

THE BUDDHA OF BREWER STREET

WHISPERS OF BETRAYAL

The Francis Urquhart trilogy

HOUSE OF CARDS

TO PLAY THE KING

THE FINAL CUT

Other titles

WALL GAMES

LAST MAN TO DIE

THE TOUCH OF INNOCENTS

NEVER SURRENDER

MICHAEL DO BBS

HarperCoWmsPublisbers

This is a work of fiction. Apart from well-known historical figures and events, the names,

characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author's imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

HarperCollins Publish

77-85 Fulham Palace Road,

Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Published by HarperCollins Publish 2003 135798642

Copyright Michael Dobbs 2003

Michael Dobbs asserts the moral rig

ht to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 0 00 710725 0 ISDN 0 00-7107-26 9 (Udde-ftkk-) Typeset in Meridien by Palimpsest Book Production Limited, Polmont, Stirlingshire

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Limited, St. Ives plc

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted,

in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

ISBN 0 00 710725 0

Jacket photographs AKG, London (Winston Churchill) & Corbis (White Cliffs of Dover)

Author photograph by Robin Matthews

HarperCollins Publish www.hamercollins.no.uk

V1.1 - August 26, 2012

FOR RACHEL

Winston Churchill's literary life was extraordinary. It encompassed histories, biographies, his own memoirs, speeches, many hundreds of articles, short stories and even a novel. In 1956 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. Yet amongst all this prodigious outpouring, one of the most inspiring pieces is also one of the least known a private article he wrote for his family and which wasn 't published until after his death. It is entitled "The Dream'. It concerns a conversation with his father's ghost, which he conducted while copying an oil portrait of his father that had been damaged.

PROLOGUE

Ascot, 1883.

The boy was small, only eight, the youngest in the school. Red-haired, blue-eyed, round in face, and nervous. He had been at the school only a term and was not popular. One of the older pupils had written home that this new boy was 'irksome'; the headmaster already found him intolerable. "A constant trouble to everybody and is always in some scrape or other," the headmaster wrote to his parents. "He cannot be trusted to behave himself anywhere."

The boy didn't fit in. And he was about to discover that failing to conform carried with it a heavy price, even for an eight-year-old.

St. George's School was a private educational establishment of four teachers and forty pupils, set in woodlands that had once been the ancient hunting forests of Windsor. It couldn't claim much of a tradition since it was only six years old, so it sought to make up for that by charging outrageously high fees. It made the place instantly exclusive. Perhaps that was why the boy's father, a man habitually committed to over-extending himself, had found the place so attractive. Anyway, it was time for his son to move on; up to that point he'd been educated by private tutors and seemed ill at ease amongst other boys he'd developed both a nervous stammer and foul temper. But that, as his father had written to the headmaster, was what he had been sent to St. George's to cure.

He was almost a year younger than any of the others, but within days of his arrival, perhaps seeking the approval of the older boys, he had leapt onto a desk and begun to recite a bawdy song he'd learnt from some of his grandfather's stable lads. Only his recent arrival saved him from a punishment harsher than being sent to bed without his supper.

Yet the boy carried with him his own sense of justice, and the following day he felt not only hungry but also poorly treated. After all, St. George's was one of the most expensive schools in the country: he felt sure his father hadn't sent him here to starve. So, in order to balance the scales of elementary justice, he had sneaked into the basement kitchens and stolen a pocketful of sugar. Inevitably he'd left considerable evidence of his crime spilled upon the counter, so the kitchen staff had reported the loss to the headmaster, the Reverend Herbert William Sneyd-Kynnersley.

'Mr. K', as he was known to the pupils, was tall, almost gangling, mutton-chopped and sandy-haired, a graduate of Cambridge with very distinctive ideas about education. To some he was a man of impeccable standards and something of a reformer, a schoolmaster who liked nothing more than to join in with his pupils while they swam naked in the pond or pursued him on a paper chase through woodlands they called the Wilderness. For others, however, he was nothing less than a ruthless brute, who punished pupils so savagely that he would not stop beating them until they bled. It was also remarked upon that, for some reason no one either could or wished to explain, Mr. K seemed to pay particular attention to those with hair of a colour even more red than his own. His childless and overwrought wife had red hair, and pupils with similar colouring seemed to be summoned frequently to the headmaster's study. The young boy had been dubbed 'the red dwarf' the day he arrived, and he seemed to spend more time in the study than most.

For Kynnersley, chivalry, posture and truthfulness were the highest virtues attributable to an English gentleman. The boy's relationship to these virtues was, in Mr. K's opinion, 'like a rainbow in the night'. His habits and language belonged more to the stable yard than the schoolyard, he disliked sports, was constantly late, had few friends and was rebellious with the teachers. There seemed no one in any part of the school who seemed capable of exerting a positive influence on him, with the possible exception, it was noticed, of the gardener. He was a child doomed to failure.

There was also the matter of the stolen sugar. When, at morning assembly, the miscreant was instructed to do his duty and to own up, the entire school had remained silent. But Kynnersley knew there would be tell-tale traces, and there were. In the boy's pockets. Both of them. In such circumstances, the Reverend Kynnersley found his duty clear.

The boy stood in the entrance hall outside the headmaster's study and considered what lay ahead. He knew of the punishments, had heard the cries of others even as he sat at his desk, had seen the welts at bedtime and knew of the desperate sobbing beneath the covers from boys much older than he. Now it was his turn.

He gazed at the clock, ticking so slowly, then up at the leering faces of the stuffed fox heads on the wall. He paced quietly in an attempt to compose himself, then fiddled with the ornate carvings of the mock Tudor fireplace, trying to find something for his fingers to do other than to tremble. On one side of the mantel stood the figure of a husband, on the other side stood his wife, separated by the fire. Just like home.

Suddenly the door to the study opened. Towering in it stood the headmaster. The boy wanted to run, every ounce of common sense screamed at him to flee. He strode forward.

The study was not large. It was dominated by two French windows that looked out onto the lawn and to the woodlands of the Wilderness beyond. Near the fireplace was a wooden block. It was upon this block that the Reverend Kynnersley had sat and toasted tea cakes for Churchill's mother when she had first brought him to this place. Neither of his parents had been back since.

On the back of the door hung a straw boater. It was a favourite item of the headmaster, one he wore throughout the summer and would raise in greeting to all visitors. Beneath the boater, hanging from the same hook, was a length of hazel cane. That, too, judging by the splayed end, had been raised with equal frequency.

The boy was ordered to take down his trousers and underwear, and to raise his shirt. He did as he was told. The Reverend Kynnersley, cane in hand, adjusted his gold-framed spectacles.

"You're a thief, and you will have your nasty little habits beaten out of you. Do you have anything to say?"

What was there to say? Sorry wouldn't save him, and anyway he didn't feel in the least sorry. Only scared. And thankful that they hadn't noticed the apple he had stolen at the same time.

Kynnersley nodded towards the wooden block. The beating block. It was whispered about between the boys, and no one ever came back bragging. The boy shuffled forward, his trousers around his ankles, like a prisoner in chains.

Eight is such a tender age to deal with adversity, but perhaps lessons learned so young are those that endure. Certainly the Reverend Kynnersley thought so, which is why he persisted in trying to flog the qualities of an English gentleman into his pupils. Break them while they are young, the younger the better, and rebuild them in a better mould. It's what had made an empire.

/> The boy's thoughts didn't reach so elevated a plane. He was putting all his concentration into controlling his bladder and denying the flood of tears that demanded to burst forth. He knew he would cry, and scream, as they all did, but not yet. Sunlight flooded in through the French windows and he struggled to look out at the woods beyond, trying to imagine himself romping through the Wilderness, a million miles from this block.

Suddenly, he thought he saw a shadow at the window, a silhouette that looked remarkably like his father. But it couldn't be, his father had never come to the school, not once. He was always at a distance, somehow untouchable, elevated. The boy adored his father no, worshipped him rather than adored, as one might worship a god. And feared him, too. Yet the greater the distance that stood between him and his father, the more eager he grew to bridge it. The less he knew about his father, the more the son invested him with almost heroic powers; the less he heard from his father, the more ferociously the young boy clung to his every word.

Never cry, never complain, his father had instructed, for they will only take advantage of your weakness.

So throughout that thrashing, he refused either to cry or to complain. The only sound to be heard was the swishing of the hazel branch, which fell with ever greater force as Kynnersley insisted that the boy submit. Again, and again. But the boy's fear of Kynnersley was as nothing compared to the fear and adulation he felt for his own father, standing there in the doorway. And when the pain became extreme, unbearable, he cried out for his father, but only inside.

They had to get two of the older boys to help him back to his room.

"You are a thief," Kynnersley shouted after him from the doorway of his study, struggling to smooth the creases in his self-control. "You'll never come to any good. You hear me? Never!"

Once alone, Winston Churchill sobbed into his pillow until there were no more tears left to shed. In later years he would cry many times, but never in fear.