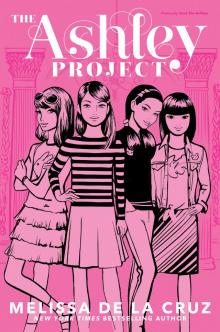

The Ashleys

Melissa de la Cruz

For Mattea Katharine Johnston, my sweet baby girl

and

Jennie Kim, BFF, for spilling the beans, sharing her memories, and always being an inspiration

You wanted to be a member of the most powerful clique in school. If I wasn’t already the head of it, I’d want the same thing.

—Heather Chandler, Heathers

I refuse to join any club that would have me as a member.

—Groucho Marx

1

THE NOT-SO-NEW GIRL

LAUREN PAGE SMOOTHED DOWN THE folds of her short plaid skirt and crossed her legs so that she could admire the shiny new black-and-white Chanel spectator oxfords on her feet a little better. They looked so cute with her thick cashmere socks scrunched down just above the ankle, she thought. She’d been wearing the same green plaid uniform to Miss Gamble’s all her life, but she was in the upper form now—seventh grade—which meant saying good-bye to her boring old Buster Browns and hello to the first boy-girl dance with the hotties from Gregory Hall, which was only three weeks away. And as far as she was concerned, upper form meant a whole new Lauren.

She leaned back on the plush, baby-soft leather seat in her dad’s sparkling new Tesla and pressed a button that flipped a mirror on the console in front of her.

Sometimes she couldn’t believe it herself. The girl who smiled back from the mirror looked nothing like the old Lauren. This one had pin-straight chestnut brown hair that fell softly on her shoulders and shone with reddish and caramel gold highlights, a killer spray tan, and cheekbones so sharp they could cut ice. Lauren felt a little like those young starlets who lost so much weight and started looking so hot that people whispered they’d had major plastic surgery. Lauren turned her head sideways to try and get a good look at her profile. Her nose certainly looked different now that her baby fat had melted away.

“Nervous?” a voice asked from the driver’s seat.

Lauren stopped preening and raised a carefully plucked-by-Anastasia eyebrow at the speaker via the rearview mirror. “Should I be?” she asked Dex, her father’s seventeen-year-old intern and personal pet project who, when he wasn’t dreaming up social media schemes for her father as part of his “regular” job, was part brother, part bodyguard, and full-time chauffeur.

“Maybe, because you’re still ugly.” Dex laughed.

“Takes one to know one,” Lauren said, sticking her tongue out at him and feeling suddenly anxious. What if Dex was right? She checked the mirror again. A smoldering, gray-eyed brunette beauty glared back at her. No, there was no way. He was just being a smart-ass as usual.

“You shouldn’t care so much what people think. Seriously, it’s not attractive,” he said, as he took a sharp turn down a curve and Lauren had to clutch at the hand rest to keep from sliding down the length of the backseat.

“Um, did Dr. Phil die or something? Because ‘Dr. Dex’ has a slightly stupid ring to it,” Lauren retorted. Easy for him to say, she thought. Dex had always been popular and was criminally good-looking, even after he shaved off his pretty-boy curls to sport a Justin Timberlake buzz cut. He was smart, too—graduating early from prep school, where he had been captain of the lacrosse, crew, and soccer teams, and taking the year off before enrolling in Stanford’s accelerated computer program. Whereas Lauren had been going to Miss Gamble’s all her life, and no one ever talked to her unless it was to ask for answers to the social studies quiz.

But all that was going to change this year.

She looked out the dark-tinted car window at the familiar roller-coaster streets of San Francisco’s Pacific Heights. The exclusive neighborhood’s palatial Victorian mansions didn’t look intimidating anymore; some of them looked small, even downright dinky.

Life had taken a turn for the ultra-luxe ever since YourTV.com went public last year. The video-sharing website was her father’s brainchild, a deceptively simple idea that allowed anyone on the planet to be a star in the cyberuniverse. The site exploded suddenly and without warning, catapulting the family from their shoebox-size Mission District one-bedroom walk-up to a grand estate of their own in the Marina, with an unparalleled view of the bay and their own helipad on the roof.

Dad was the newly crowned king of Silicon Valley and had made the covers of Fortune and Forbes, and Mom had gone from protesting animal testing on the sidewalk to chairing benefit dinners for African orphans. And Lauren, who had made do with thrift-store castoffs and clearance-bin remnants all her life, suddenly found herself at designer boutiques on Maiden Lane with a personal shopper hanging on her every word.

Last year she was a financial-aid pity case, fretting over whether anyone at school would notice that her blue cashmere sweater had been bought secondhand at the school’s charity shop. This year her sweater was a nine-hundred-dollar one with a fancy Italian label. Lauren had been worried about getting a stain on it, until her dad—who used to pay the grocery bill with change from the kitchen jar whenever his graduate teaching assistant stipend ran out—had told her that she wouldn’t have to worry about anything ever again. At least not where pricey designer clothes were concerned. Well, then. Bring on the twelve-ply Mongolian cashmere.

Lauren grabbed her tall, frosty Voss water bottle to calm her nerves.

Because Dex was right. She was a little nervous. A head-to-toe Emma Roberts–like makeover was one thing, but there were still the Ashleys to contend with. Lauren could see them now, giving her the daily head-to-toe fashion evaluation and shaking their heads in mock disgust. Even if there was a school uniform and all students were supposed to look the same to eliminate “status consciousness,” the Ashleys always looked like they stepped out of a J. Crew catalog, while Lauren looked like she’d stumbled out of a Disney Channel show. They never let her forget it, either.

Lauren clenched her jaw. What if they saw through her six-hundred-dollar haircut and carefully accessorized uniform and decided she was just the same old dork she had always been?

The old Lauren was a meek, frizzy-haired girl who sat in the back, whom no one ever paid attention to until her name was called at the end of every year during Prize Day, when the whole school gathered in the main hall, all the girls wearing ivy-covered garlands in their hair while the headmistress gave out the awards for the top student in every subject. She would stand for what seemed like an excruciatingly long time while Miss Burton read out the list of awards she’d received, in every subject except gym—mercifully, she escaped that one mortification.

What if they looked at her and saw the same Lauren from last year?

She would not allow that to happen. She dug her Black Satin manicure into the Tesla’s thick upholstery, leaving ugly grooves in the Italian leather. Uh-oh. That was going to cost a fortune to fix. Then she remembered with relief that a fortune was exactly what she had right now. And like Angelina Jolie, she was going to use her money to do something good for a change.

First she was going to join the Ashleys. And then she was going to destroy them. She wanted to change the world one day, and she was going to start by making the seventh grade a better place to be.

The car pulled up to the main gates, where a slew of the latest eco-cars were lined up, depositing their precocious charges on the sidewalk—the rosy-cheeked daughters of the most elite families in the Bay Area. Several girls who lived down the street in the multimillion-dollar townhouses Lauren had just passed were casually walking up the hill, Alexander Wang messenger bags slung across their chests.

Lauren spied the Ashleys in their usual before-school hangout by the stone bench in front of the playground, the three of them holding matching venti decaf soy lattes and looking beyond bored. They looked so sweet and innocent—not at all like the soul-destroying creatures they really were. She inhaled and said a little prayer

to whatever gods watched over made-over twelve-year-olds with secret intentions.

Today was the first day of the rest of her new life.

2

ASHLEY SPENCER IS ONLY ALLERGIC TO WEAKNESS

“AHEM. MISS ASHLEY, YOUR MOTHER wants to remind you to take your EpiPen.”

“I will. God, she’s such a nag!” Ashley Spencer thanked the elderly butler who had been in her mother’s family for years and dismissed him from the kitchen with a nod. She rolled her eyes and stuffed the slim silver needle for injecting the shot of epinephrine—the only thing that would keep her alive in case she even breathed nut aroma—into her Proenza shoulder bag’s secret compartment, next to her strawberry-scented lip gloss.

Her mom was so Nazi about her allergy, ever since she’d almost killed Ashley on her fourth birthday, when the exquisite French chocolate cake she served at the party turned out to have had a trace amount of hazelnuts in the batter.

Since then Ashley refrained from eating anything that wasn’t cooked for her by the Spencers’ gourmet chef. Her nut-free lunch was already prepared in a cute Japanese lunchbox that she’d found in Tokyo that summer. It was made of cool white plastic and decorated with bug-eyed anime characters. Tokyo was so eye-opening—the style there was très unconventional, and Ashley had bought the lunchbox in an attempt to emulate the famous Harajuku Girls. But now, looking at it, she briefly wondered if the lunchbox was a little too goofy and “sixth grade” somehow and made a mental note to find out if there were such things as Hermès Thermos containers.

She turned off the mirrored flat-screen TV that hung in the breakfast nook and left her cereal bowl and juice glass on the island counter for the maid to clean. The clock on the smooth, stainless-steel face on the Thermador oven told her it was twenty-five minutes to the first bell, but instead of dashing out the door she took her time, removing a breath strip from a tiny plastic case in her pocket and letting the gooey green film melt on her tongue while she gathered her things. She was supposed to be at the Fillmore Starbucks by now, and the other Ashleys were probably waiting, but she didn’t care. They could wait. As if they would walk to school without her, hello.

“How about a kiss?” asked her mother, coming out of her study and finding Ashley brushing her hair in front of the grand Louis Quinze mirror hanging in the main hall. “Did Darby remind you to pack your allergy kit?”

“For the hundredth time, yes, Mom. And careful with the hair,” Ashley ordered, putting her hairbrush away and allowing herself to be kissed on both cheeks. She wrinkled her nose at her mother’s heavy patchouli perfume. Couldn’t Mom switch to something like Chanel No. 5? She gave her mother’s outfit a cool once-over. “I hope you’re not wearing that for this afternoon’s tea,” she commented, letting the inflection in her voice tell her mother that it wasn’t a good idea.

Matilda Spencer crossed her arms and gave her daughter a bemused look. “I’m not, but why, is there something wrong with it?”

“Mom, 1998 called, they want their jeans back. Could you please put on the new skinny jeans we bought at Saks on Saturday?”

Ashley shook her head. Her mother was the most beautiful woman she knew, and not just because they looked so eerily alike they could be sisters. The two of them had long, lustrous golden hair; clear, cornflower blue eyes; and pale ivory skin without a hint of a freckle. If Mom was Gwyneth Paltrow, Ashley was just a younger, smoother version, both of them delicate blondes with enviably thin arms and speedy metabolisms.

Their similarities ended with fashion, though. Ashley was always red-carpet-ready, even when she was just going to school, finding numerous ways to accessorize her uniform—wearing thick black tights instead of the chunky socks she’d made so popular with the plaid skirt last year, finding high-heeled patent-leather Mary Janes that fit the saddle-shoe requirement, and wearing James Perse T-shirts underneath the V-neck sweaters instead of the tidy blouses with their Peter Pan collars. Her mother, unfortunately, stuck to a casual wardrobe of Peruvian handmade knits, plastic Crocs, and jeans she’d owned since college at UC Berkeley. Matilda never really cared too much about clothes. It was such a waste.

Her mother was hosting the annual Miss Gamble’s mother-daughter “welcome back” tea in the sunroom that afternoon with Lili’s mom, and Ashley wouldn’t normally care what anyone thought, since her mother was always the prettiest woman in the room, but sometimes she wished Matilda would make more of an effort to look more fashionable. Lili’s mom was always totally done up in the latest designer duds, with perfect hair, nails, and makeup, and she looked like the quintessential private-school parent.

While Ashley chastised her mom for her fashion sense, she heard her father come jogging down the stairs in a holey T-shirt and yoga pants, his guru following behind.

“Off to school, precious?” he asked, doing sun salutations in the foyer while Bodhi helped balance him. “Ready for the new year? You know you’ll kick ass! Won’t she, my love?” he asked, turning to his wife and giving her a kiss on the nose.

Her mother giggled and looped her arm around her husband’s, and for a frightening moment it looked like the two of them would actually start to make out in front of their daughter, but thankfully her father got distracted by his trainer, and the cringe-worthy display of affection was averted. Ashley breathed a sigh of relief.

When she was little, she loved having her parents at home all the time, but now it was getting annoying. Neither of them worked in any real sense—Dad “managed” the family trusts and Mom worked on her “art,” both of them having inherited a huge chunk of change from their families. Which meant they had ample time to suffocate their only child, although they tried to be “cool” parents: Bedtime was flexible on the weekends, they didn’t nag her about her grades too much, and her mom didn’t nose around her online profiles like other mothers did.

“You’re not going to be here for the tea, are you?” she asked her father. “Please don’t.” She didn’t want him wandering around the house barefoot in his sweats, or strumming his guitar while the whole seventh-grade class tittered. Seriously, parents could be so embarrassing. The Nob Hill Gazette had once crowned her parents San Francisco’s “It Couple,” but that was a long time ago, before she was even born. They were such goofballs now, it was hard to imagine them as ever being so superglamorous.

Ashley allowed herself to be hugged by the two of them and walked out the door, checking once again to make sure she had that antiallergy shot in her purse. It made her feel better knowing it was there, especially since almost no one knew about her condition, and she liked to keep it that way.

No way in hell was she going to be dumped in with Cass Franklin, that freak who had to eat in her own screened-off quarantined section of the refectory, alienated from all the other kids. Ashley had pretended for so long that she liked living on nothing but yogurt and spelt bread and raw vegetables that she almost believed it.

She was Ashley Spencer, the undisputed, unshakable leader of the Ashleys. No one told her what she could and couldn’t eat.

Owning up to her allergy was admitting weakness. Seventh grade was a saddle-shoe jungle. And Ashley Spencer made sure everyone marched to the beat of her iPod.

3

BFF OR WORST ENEMY? FOR ASHLEY LI, IT’S THE SAME THING

HOW MUCH LONGER DID SHE have to wait? Another five minutes? Ten? Fifteen? Her mother would go ballistic if she got slapped with a late notice on the first day of school. Three late notices and you had to face the Honor Board—which was kind of out of the question for her, since she was on the Honor Board.

Ashley Li checked the time on the dangling golden lock of her tan leather Hermès Kelly watch, which she wore strapped around her wrist like a lariat. If they weren’t at Miss Gamble’s in fifteen minutes, Miss Moos, the dreaded school secretary with the creepy hair weave and onion-bagel breath, would soon be ringing their parents, inquiring in that quavery voice of hers as to why their little girls weren’t in school that morning.

&n

bsp; She took a sip from her cardboard coffee cup. Chai soy decaf latte. It tasted like extra-hot crap, but she pretended to like it because Ashley Spencer loved it, and the point of being friends with Ashley Spencer—the whole point of being in the Ashleys—was that they all liked and did the same things. They had decided back in fourth grade that the Ashley thing was too confusing, so they would go by very cute nicknames instead. All except for Ashley Spencer, of course, who somehow retained the right to be called “Ashley.” Lili was a much chicer name than Ashley anyway, Lili decided.

Where was the biatch? It drove her crazy how Ashley never seemed to notice the time.

You’d think the girl would at least try to be on time for the first day of junior high. Lili sighed. She’d have to lie to her mom again to explain the disciplinary note.

Whenever Lili messed up at school, she was sure to feel the wrath of (Nancy) Khan. Her mother, who had kept her maiden name and used to be the highest-paid female partner at Willbanks, Eliot, and Dumforth (and before that, editor at the Harvard Law Review), was now a full-time SAHM: a stay-at-home mom—or in her case, a socialite-at-home mom, serving on all of the committees and volunteer boards at Miss Gamble’s. She didn’t accept anything less than perfection from her only daughter.

She should just leave. Forget Ashley. Yeah, right. As if she could ever desert her best friend. That was the problem. Ashley could make anything better, more fun, and less completely mundane. She thought about the stickers from last year that Ashley had made for them to put on select lockers. The stickers read “The Ashleys: SOA” in script on silver foil. No one but the three of them knew what the letters stood for, and it drove the whole class crazy trying to guess. SOA stood for “Seal of Approval,” which should have been glaringly obvious, since only the cool girls in class got the sticker.

Lili gripped her coffee cup tightly, took an agonized sip of the drink, and contemplated tossing it into the trash. They’d gotten into trouble for the stickers once the faculty got wind of the incident; the girls were chastised because their little prank promoted “clique culture,” which was supposedly against school policy. Uh-huh. Good luck with that.