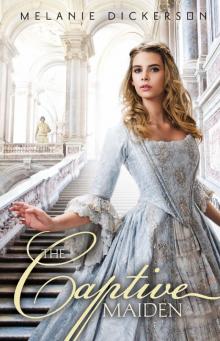

The Captive Maiden

Melanie Dickerson

THE

CAPTIVE

MAIDEN

MELANIE DICKERSON

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Acknowledgments

Preview

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

About the Author

Other books by Melanie Dickerson

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

Spring, 1403, Hagenheim Region

Gisela huddled by the fire in her attic chamber, clutching the miniature portrait that fit in her hand. The artist had painted it the year before, when Gisela was seven. Father had been so handsome.

Now that Gisela was eight and Father was gone, life could never be the same. If only she had stayed seven forever.

“I love you,” she whispered, kissing her portrait-father’s cheek as a tear dripped off her chin.

Her stepmother’s unforgiving wooden pattens clicked up the steps that led to Gisela’s attic room.

“Gisela!” Evfemia called.

She thrust the portrait back inside the hole in the fireplace wall and pushed in the loose brick, then kicked the ashes into the fire to smother it.

“Gisela! What are you doing?” Evfemia towered over her. “You have cinders on your hands. And your feet!”

Gisela made her face a blank as she stared at the floor.

Lighter footfalls clattered up the stairs and Gisela’s two stepsisters pushed against their mother’s silk skirt, staring out from behind her.

Irma was the oldest, and her long, thin face and squinty-eyed expression made Gisela wonder if the girl had a bad taste in her mouth. She had the same limp brown hair as her sister, Contzel, but that was the only trait they had in common. Contzel’s cheeks were round and chapped pink, and her face was forever relaxed, her mouth open, as if she had just awakened from a nap.

Frau Evfermia raised one brow. “Go down to the stable and help the groomsman get the horses ready.”

When Gisela hesitated, Evfemia screamed, “Obey me this moment or I will throw you out into the cold!”

Gisela darted forward, hoping to run past her snarling, red-faced stepmother and her two smirking stepsisters. But Evfemia reached out and snatched Gisela’s hair, wrenching her head halfway to the floor before she let go.

Gisela stumbled but kept running down the stairs and to the stable, rubbing her stinging scalp.

When she arrived, Wido the groomsman was leading one of the carriage horses out of the paddocks.

“Frau Evfemia sent me to help you.”

Old Wido frowned at Gisela. “She shouldn’t be sending you, the young miss, to help me with the horses.”

Gisela wiped her nose with the back of her hand and shook her head. “I want to help.”

Gisela went in to lead the second horse out. She stood on tiptoe to rub the black horse’s cheek. “Come on, boy.” Gisela sniffed and took a deep breath. The big horse nudged her shoulder and let her lead him outside.

Following Wido’s instructions, she positioned the horses before the carriage and kept each one steady as the harnesses were put into place. Just as both were hitched and ready to go, Gisela’s stepmother, along with Irma and Contzel, came out of the house and flounced toward them.

Irma stared at Gisela with cold, contemptuous eyes as she waited for Contzel to climb in.

“Go ahead, darling,” Frau Evfemia crooned, helping Irma up the step the groomsman had placed before them.

Her stepmother glanced down at Gisela with raised eyebrows, then climbed into the carriage and latched the door. They had said nothing about where they were going or when they would be back. As they left, the pain inside her chest increased until it threatened to overwhelm her.

“Why would I care where they’re going? I don’t care if I’m all alone. I like being alone.” The pain lifted a little, so she went on. “I don’t care if they hate me. I don’t care about them at all.” She clenched her fist. “And I don’t care if they never come back.”

Gisela went back inside the stable, feeling better than she had in a long time, and she concluded it was better not to care. The next time she felt the pain of her stepmother’s cruelty or her stepsisters’ disgust, she would remind herself that she didn’t care.

She found her favorite horse, Kaeleb. The light brown destrier hung his head over the stall door and whinnied at her. Gisella stood on a stool and rubbed his cheek and pressed her forehead against his neck. “I wish they wouldn’t come back.”

But they would.

She began helping Wido muck out the stables and fetch hay for the horses. Another thing Gisela concluded was that horses were much more lovable than people.

“Little miss, you mustn’t stay out here any longer.” Wido took the pitchfork from her. “It’s too cold. Go on to the house with you.”

Her worn-thin dress was not very warm and she was shivering. And yet, she hesitated. Perhaps if she took the blanket off her bed, she could sleep in the stable atop a pile of straw in Kaeleb’s stall. It probably wouldn’t be any colder than her fireless room.

“Go on, now.” Wido shooed her toward the house.

Relenting, Gisela turned and ran inside. She stirred up the dwindling fire in the great hall but dared not add any more wood. Her stepmother did not allow her to “waste” wood. Shivering, she stepped inside the giant fireplace and knelt among the dying embers where it was warm. Her dress was already dirty from the ashes in her bedchamber fireplace, in addition to being torn and permanently stained over most of the fabric, as it was a cast-off of a former servant, having been altered to fit her eight-year-old body. Besides, she could wash it tomorrow.

She put her cold fingers under her arms and leaned her shoulder against the heat of the fireplace bricks. “I don’t care what they think of me. I don’t care what they do.” If her father was here, he’d never let her stepmother deny her a fire in her room or treat Gisela like a servant. But she reminded herself she didn’t care.

She imagined her father and mother in heaven, picturing how they would welcome her—hugging her, kissing her, their arms warming her. The thought was so comforting, she relaxed inside the fireplace, leaning her cheek against her folded hands.

Gisela woke to cackling laughter. She opened her eyes to her stepmother and stepsisters standing in front of the fireplace.

Irma pointed her skinny finger at Gisela, her face twisted in a sneer. “Lying in the cinders like an addlepate.”

“She’s filthy.” Contzel wrinkled her nose.

Evfemia planted her fists on her hips. “Get up from there, you ridiculous girl, and go to your chamber. You shall scrub every inch of the floor from this fireplace to your door, as you couldn’t possibly make a step without strewing filth everywhere. I don’t know where you got such a notion, to sit in the fireplace among the cinders.”

&nbs

p; Gisela stood.

Irma clapped her hands and squealed. “I know. Instead of Gisela, we’ll call her Cinders-ela.” All three of them laughed.

“Cindersela!” “Always dirty!” “The girl who smells like cinders and horses.”

With the taunts and laughter ringing in her ears, Gisela walked with her head held high all the way up the stairs to her room.

Gisela changed out of her ragged work clothes, put on her nightdress, and washed her face in the cold water of her basin. Today she had washed every window on all three floors of the house, she’d helped Wido muck out the stables, and she’d mended two of Irma’s dresses. She had cleaned up the mess Contzel’s puppy made in the dining hall. And she cleaned the mess the puppy made on the stairs. And in the solar. And in Contzel’s chamber. And then the snippy animal bit her on the ankle.

She did not like that dog.

Gisela wrapped herself in a blanket and sat on the bench in front of her window. Across the hills, over the city wall to the north, stood Hagenheim Castle, barely visible through the deepening night except for its five towers interrupting the horizon. The castle towers’ lit windows seemed to carry her back to a year ago.

When she was still seven, and before her father died, the Duke of Hagenheim and his oldest son, Valten, had come to buy a horse from her father, because, as Father said, he bred and raised the best horses in the region. Valten wanted a war horse, a destrier that would serve him as he practiced jousting and other war games.

The two of them, Duke Wilhelm and his son, rode up the lane to her house. Duke Wilhelm and her father greeted each other like old friends. The duke’s son was fourteen, and Gisela had been seven. Valten was already quite as tall as her father and broad-shouldered. She remembered his hair was blond, and he’d looked at her with keen eyes and a sober expression.

Within the first moments, she decided she did not like him. He had come to take one of her horses away, and worst of all, this boy meant to ride her horse in the lists. She didn’t want one of her horses competing in the dangerous joust, risking serious injuries with each charge.

But the boy and his father treated the horses gently and respectfully. From several feet away she had watched as they examined all the youngest destriers. By the time the duke’s son made his choice, Gisela realized he would love the horse, would take care of him. The horse would have many adventures with the duke’s son, more than Gisela could give him.

As their fathers settled their price, Gisela watched Valten — she was supposed to call him Lord Hamlin, as he was the Earl of Hamlin, but she thought his given name suited him better — as the young earl rubbed the horse’s nose and cheek and talked softly to him.

“He likes carrots.”

Valten turned and looked at her. “Then I shall make sure he gets some.”

Valten displayed compassion, where her new stepmother and stepsisters showed none. And even though he was taking away one of her horses, she could not hate him. In her mind, she had believed he would treat the destrier well.

Tonight as it grew dark, she wondered what Valten and the horse were doing. Was the horse well? What had Valten named him? Did the horse like training for the jousting tournaments? Were they both happy? Her thoughts, as they often did, gradually focused on Valten alone, the handsome young heir to the duchy of Hagenheim. Did his mother kiss him good night the way her father used to kiss her? Valten was probably too old for that. Was he still handsome? Who would he marry? His bride would be pretty and certainly would not smell like cinders and horses.

Gisela imagined herself grown up, wearing beautiful clothes, and Valten coming to find her and asking her to be his bride. Valten would want to marry someone kind, wouldn’t he? Someone who believed in goodness and mercy and love.

And in spite of the fact that her father was dead and her stepmother and stepsisters hated her, she did believe in goodness, mercy, and love.

Valten would never be cruel. He would be kind and good. At least, she liked to think so.

Gisela turned away from the window and the sight of the castle towers in the distance. She climbed into bed, clutching her blanket to her chin, and closed her eyes. “Guten nacht, Valten.”

Chapter

1

Nine Years Later … Spring, 1412, a few miles west of Hagenheim.

Gisela rode Kaeleb over the hilly meadows near her home, letting the horse run as fast as he liked. The morning air clung to her eyelashes, as a fog had created a misty canopy over the green, rolling hills. The wall surrounding the town of Hagenheim stood at her far right, with the forest to her left and her home behind. Hagenheim Castle hovered in the distance, its upper towers lost in the haze.

If her stepmother found out she’d been riding one of the horses without permission, as Gisela often did, she would find some way to punish her. But Gisela didn’t care. She could leave any time she wanted to, as she had hidden away the money her father had given her just before he died. She chose to stay, at least for now, because of her love for the horses.

Gisela would probably be forced to leave soon. Her stepmother would end up selling all the horses, or would marry someone despicable, or would create some other type of intolerable situation. When that happened, Gisela planned to go into the town and find paying work, perhaps tending a shop or serving as a kitchen maid at Hagenheim Castle.

Evfemia thought she controlled Gisela. But some day her stepdaughter-slave would be gone.

She didn’t want to think about her stepmother anymore. Instead, Gisela focused on the wind in her hair as she flew over the meadow on Kaeleb’s back. The cool air filled her lungs almost to bursting. For this moment, she was free.

Kaeleb loved these rides as much as she did. She could sense it in the tightness of his shoulders, in the way he fairly danced in anticipation before she even tightened his saddle in place.

Movement to her left made her turn her head slightly. A horse and rider emerged from the trees and stood watching her from the edge of the meadow.

Gradually, Gisela slowed Kaeleb. She could tell even from this distance the horse and rider were both taller than average. The bare-headed man had short, dark blond hair and wore a green thigh-length tunic that buttoned down the front. His horse was the same size and color as Kaeleb.

The man reminded her of Valten — more appropriately known as Lord Hamlin.

The duke’s oldest son had been away for two years, but she’d heard of his return. Gisela figured he would be about twenty-four years old now, as it had been ten years since he and his father had come to buy a horse.

She turned Kaeleb back the way they had come. But instead of riding away, she stared at the man. He seemed comfortable in the saddle, and he held his head high and his back straight. No doubt Valten was proud and self-possessed, but was he also still the kind, gentle boy she had dreamed about as a child?

Probably not. But why should she care? She had ceased daydreaming about him years ago, when she realized she was but a servant now and no longer the wealthy land owner’s daughter whose father had been so friendly with Duke Wilhelm.

She glanced down at her coarse woolen overdress. She’d tucked her skirt into her waistband, exposing the leather stockings she wore to cover her legs while she rode, since she hated riding sidesaddle. Her feet were bare and dirty, and her hair was completely unfettered, as she liked to feel the wind lifting and tossing the long strands.

She wouldn’t want the duke’s son to see her looking this way, if this was indeed Valten. He would mistake her for a peasant, which, when she thought on it, she might as well be, given her position in her stepmother’s household.

Gisela urged Kaeleb forward, and soon they were flying back over the hills again. She wasn’t running away from the duke’s son; she had to go home, for her stepmother and stepsisters would be demanding their breakfast soon, and she still had to give Kaeleb a good brushing after their ride. Besides, Valten, the tournament champion and future leader of Hagenheim, would hardly care to get acquainted with her,

the stable hand, cook, and all-around servant for a spoiled, selfish trio of women.

As a little girl she had imagined marrying Lord Hamlin. Now, she knew it was a silly dream. Though she had once cared very much about Valten — following the reports from town of his accomplishments as a tournament champion — it was getting easier to tell herself he couldn’t be as noble and good as she had imagined. Her usual trick to keep from feeling bad — to tell herself that she didn’t care — worked nearly as well with Valten as with everything else.

Valten strolled through the Marktplatz for the first time since leaving Hagenheim two years ago. Very little had changed. The vendors were the same. Same old wares — copper pots and leather goods — carrots, beets, leeks, onions, and cabbages laid out in rows of tidy little bunches. People talked loud to be heard over the bustle of market day. They stepped around the horse dung on the cobblestones while brushing shoulders with the other townspeople. Everyone had somewhere to go, a purpose.

What was his purpose?

A restlessness possessed him, the same restlessness that had haunted his wandering all over the Continent. Entering all the grandest tournaments for two years had not eased that restless feeling. He’d succeeded at winning all of them in at least one category—jousting, sword fighting, hand-to-hand combat — but often in all categories. He still wasn’t a champion at archery, which rankled. But he couldn’t be perfect at everything.

Perhaps God had given him archery to keep him humble. Archery, and his little brother Gabe.

He couldn’t truly blame his brother. Gabe had seen an opportunity to make a name for himself and he had taken it. Valten would have done the same. And Gabe probably hadn’t intended to steal his betrothed.

He didn’t like to relive those memories. He’d forgiven his brother, and truthfully, Valten had not been in love with Sophie. He hadn’t even known her. Now he couldn’t imagine being married to her. She was Gabe’s wife, and he didn’t begrudge them their happiness or doubt that it was God’s will that the two of them were together. But he had been made to look foolish when everyone wondered why Gabehart, Valten’s younger, irresponsible brother, was marrying Valten’s betrothed.