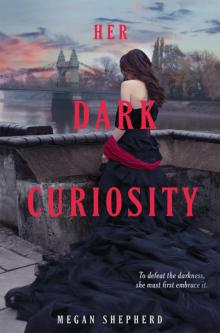

Her Dark Curiosity

Megan Shepherd

DEDICATION

To Peggy and Tim,

for a childhood filled with books & love

CONTENTS

Dedication

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Twenty-Nine

Thirty

Thirty-One

Thirty-Two

Thirty-Three

Thirty-Four

Thirty-Five

Thirty-Six

Thirty-Seven

Thirty-Eight

Thirty-Nine

Forty

Forty-One

Forty-Two

Forty-Three

Forty-Four

Forty-Five

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Books by Megan Shepherd

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

ONE

THE AIR IN MY crumbling attic chamber smelled of roses and formaldehyde.

Beyond the frosted windowpanes, the rooftops of Shoreditch stretched toward the east in sharp angles still marked with yesterday’s snow, as chimney stacks pumped smoke into an already foggy sky. On nights like these, I never knew what dangers might lurk in the streets. Yesterday morning a flower girl around my age was found frozen on the corner below. I hadn’t known her aside from glimpses in the street, one girl on her own nodding to another, but now her dark, pretty eyes would never again meet mine in the lamplight. The newspapers said nothing of her death—just one of dozens on such a cold night. I’d learned of it in slips and whispers when I made my usual rounds to the flower stalls and butcher stands. They told me she’d tried to stuff flowers between the layers of her meager clothing for warmth. The flowers had frozen too.

I pulled my patchwork quilt tighter around my shoulders, shivering at the thought. After all, a threadbare scrap of fabric wasn’t much more than crumpled flowers.

Winter in London could be a deadly time.

And yet, as I studied the street below where children trailed a chestnut roaster hoping for fallen nuts, I couldn’t help but feel there was something about the narrow streets that whispered of a certain familiarity, a sense of safety despite the rough neighborhood. The tavern owner across the street came out to hang a sparse holly wreath on her paint-flecked door, getting ready for Christmas in a few weeks. My thoughts drifted backward to memories of mincemeat pies and presents under a fir tree, but my smile soon faded, along with the fond remembrances. What good would presents do me now, when death might be just around the corner?

I returned to my worktable. The attic I let was small, a narrow bed and a cabinet missing a drawer arranged around an ancient woodstove that groaned into the night. My shabby worktable was divided in two halves; the right-hand side contained half a dozen twisted rosebushes in various states of being grafted. A flower shop in Covent Garden paid me to alter these bushes so that the same plant would produce both red and white flowers. The meager profit I made helped pay for the rent and the medical supplies on the left side of the table: a syringe from my previous day’s treatment, a package wrapped in butcher paper, and scrawled notes about the healing properties of hibiscus flowers.

I took my seat, letting the patchwork quilt pool onto the floor, and reached for one of the glass vials. Father had developed this serum for me when I’d been a baby, and until recently it had kept the worst of my symptoms at bay. Over the past few months, however, all that had begun to change, and I was growing more ill: muscle spasms, followed by a deep-seated ache in my joints, and a vertigo that left my vision dulled. The instant I touched the vial, my hand clenched with a sharp tremor, and the small container slid from my fingers and shattered on the floor.

“Blast!” I said, hugging my quaking hand to my chest. This was how the fits always began.

As flickering shadows from my lamp threw beastlike shapes on the roof, I cleaned the broken glass and then unwrapped the butcher’s package and smoothed down the edges. The smell of meat filled the air, ironlike, only just beginning to rot. My head started to spin from the odor. I lifted one of the pancreases. The organ was the size of my fist, a light fleshy color, shriveled into deep wrinkles. The cow must have been killed yesterday, maybe the day before.

Its death might mean my life. I’d been born with a spinal deformity that would have been fatal, if my father hadn’t been London’s most gifted surgeon. He’d corrected my spine, though the operation resulted in a scar down the length of my back and several missing organs that he’d been able to substitute in his desperation with those of a fawn. My body had never quite accepted the foreign tissue, resulting in the tremors, dizziness, and need for daily injections.

I wasn’t certain why the serum was failing now. Perhaps I was becoming immune, or the raw ingredients had altered, or perhaps now that I was growing from child to woman, my body’s composition was changing, too. I’d outgrown his serum just as I had my childish respect for him. His serum had only ever been temporary anyway, lasting a day or two at most. Now I was determined to create something even better: a permanent cure.

The pancreas’s puckered flesh yielded under my scalpel’s sharpened blade, separating like butter. It required but three simple incisions. One down the length. One to expose the glycogen sac. Another to slice the sac free and extract it.

I slid over the tray clinking with glass vials, along with the crushed herbs I’d already mixed with powders from the chemists’. This work had a way of absorbing me, and I scarcely realized how the afternoon was passing, or how cold the air seeping through the window was growing. At last I finished this latest batch of serum and waited impatiently to see if the various ingredients would hold. In order to be effective, the disparate parts would need to maintain cohesion for at least a full minute. I waited, and yet after only ten seconds the serum split apart like a bloated eel left too long in the sun.

Blast.

It had failed, just like all the times before.

Frustrated, I pushed my chair back and paced in front of the twisted rosebushes. How much longer could I go on like this, getting worse, without a cure? A few more months? Weeks? A log cracked in the woodstove, sending hot light licking at the stove’s iron door. The flames flickered like those of another fire long ago, my last night on the island. I had been desperate then, too.

Montgomery stood on the dock, the laboratory where he’d helped Father with his gruesome work blazing behind him. Waves lapped at the dinghy I crouched in, waiting for him to join me. We’d sail to London, put the island behind us, start a new life together. And yet Montgomery remained on the dock, let go of the rope, and pushed me out to sea.

But we belong together, I had said.

I belong with the island, he’d replied.

A church bell rang outside, six chimes, and a glance at the window told me night had settled quickly. I was late again, reliving memories I’d sooner forget. I grabbed my coat and threw open the door, dashing down four rickety flights of stairs until I was outside with the wind pushing at my face and the cold night open before me.

I stuck to the well-traveled, gaslit thoroughfares. It wasn’t the fastest route to Highbur

y, but I didn’t dare take the shortcuts through the alleyways. Men lurked there, men so much larger than a slip of a girl.

I turned north on Chancery Lane, which was busy at all hours with people loitering between pubs, and I hugged my coat tighter, keeping my eyes low and my hood pulled high. Even so, I got plenty of stares. Not many young ladies went out alone after dark.

In such chaos, London felt much like Father’s island. The beasts that lurked here just had less fur and walked more upright. The towering buildings seemed taller each day, as though they’d taken root in the oil and muck beneath the street’s surface. The noise and the smoke and the thousand different smells felt suffocating. Too closely packed. Ragged little children reached out like thorny vines. It felt as if eyes were always watching, and they were—from upstairs windows, from dark alleys, from beneath the low brims of wool caps hiding all manner of dark thoughts.

As soon as I could, I escaped the crowd onto a street that took me to the north section of Highbury. From there it wasn’t too far to Dumbarton Street, where the lanes were wide and paved with granite blocks, swept clean of all the refuse found in the lesser neighborhoods. The houses grew from stately to palatial as my boots echoed on the sidewalk. Twelve-foot-high Christmas trees studded with tiny candles shone behind tall windows, and heavy fir garlands framed every doorway.

I paused to lift the latch of the low iron gate surrounding the last house on the corner. The townhouse was three stories of limestone facade with a sloping mansard roof that gave it a stately air, as though it had quietly withstood regime changes and plague outbreaks without blinking an eye. It was on the quiet end of Dumbarton, not the grandest house by far, despite the fact that its owner was one of London’s wealthiest academics. I dusted off my coat and ran my fingers through my hair before ringing the doorbell.

The door was opened by an old man dressed in a three-piece black suit who might look stern if not for the deep wrinkles around the corners of his eyes, which betrayed his inclination to smile in a charmingly crooked way—a habit he gave in to now.

“Juliet,” he said, “I was starting to worry. How was your visit with Lucy?”

I smiled, the only way I knew to hide my guilt, and pulled off my gloves. “You know Lucy, she could chatter away for hours. Sorry I’m a bit late.” I kissed his cheek as if that would make up for the lie, and he kindly helped me out of my coat.

“Welcome home, my dear,” he said.

TWO

PROFESSOR VICTOR VON STEIN had been a colleague of my father’s—and the man who turned him in to the police ten years ago for crimes of ethical transgression. The professor’s betrayal of their friendship might have bothered me when I was younger and still had respect for my father, but now I thought he’d done the world—and me—a favor. I owed him even more because, for the last six months, he’d been my legal guardian.

When I’d left Father’s island, I’d followed Montgomery’s instructions to find a Polynesian shipping lane and, after nearly three scorched weeks in the dinghy, was picked up by traders bound for Cape Town. From there, the expensive trinkets Montgomery had packed bought me passage to Dakar, and on to Lisbon. I’d gotten sick on the last leg of the voyage, and by the time I reached London was little more than a skeleton, raving about monsters and madmen. I must have said my friend Lucy’s name, because one of the nurses had summoned her, and she’d taken care of me, but my good fortune ended there. One of the doctors was an old acquaintance from King’s College by the name of Hastings. A year ago he’d tried to have his way with me and I’d slit his wrist. As soon as he learned I’d returned, he’d had me thrown in jail, which was where Professor von Stein had found me.

Lucy Radcliffe told me your circumstances, he had said. Is it true what you did to this doctor?

He needn’t have asked. The scar at the base of Dr. Hasting’s wrist matched my old mortar scraper exactly.

It is, I’d said, but I had no choice. I’d do it again.

The professor had studied me closely with the observant eyes of a scientist, and then demanded I be released into his custody and the charges dropped. Hastings didn’t dare argue against someone so highly respected. The next day, I went from a dirty prison cell to a lady’s bedroom with silk sheets and a roaring fire.

Why are you doing this? I had asked him.

Because I failed to stop your father until it was too late, he’d replied. It isn’t too late for you, Miss Moreau, not yet.

Now, sitting at the formal dining table with a forest of polished silver candlesticks between us, I secretly kicked off my slippers and curled my toes in the thick Oriental rug, glad to put that old life behind me.

“An invitation arrived today,” the professor said from his place opposite me. The hint of an accent betrayed that he’d grown up in Scotland, though his family’s Germanic ancestry was evident in his fair hair and deep-set eyes. A fire crackled in the hearth behind him, not quite warm enough to chase the cold that snuck through the cracks in the dining room windows.

“It’s for a holiday masquerade at the Radcliffes’,” he continued, removing a pair of thin wire-rimmed spectacles from his pocket, along with the invitation. “It’s set for two weeks from today. Mr. Radcliffe included a personal note saying how much Lucy would like you there.”

“I find that rather ironic,” I said, buttering my roll with the hint of a smile, “since last year the man would have thrown me into the streets if I’d dared set foot in his house. He’s changed his tune now that I’m under your roof. I think it’s you he’s trying to win over, Professor.”

The professor chuckled. Like me, he was a person of simple tastes. He wanted only a comfortable home with a warm fire on a winter night, a cook who could prepare a decent coq au vin, and a library full of words he could surround himself with in his old age. I was quite certain the last thing he wanted was a seventeen-year-old girl who slunk around and jumped at shadows, but he never once showed me anything but kindness.

“I fear you’re right,” he said. “Radcliffe has been trying to ingratiate himself with me for months, badgering me to join the King’s Club. He says they’re investing in the horseless carriage now, of all things. He’s a railroad man, you know, probably making a fortune shipping all those automobile parts to the coast and arranging transport from there to the Continent.” He let out a wheezing snort. “Greedy old blowhards, the lot of them.”

The cuckoo clock chimed in the hallway, making me jump. The professor’s house was filled with old heirlooms: china dinner plates, watery portraits of stiff-backed lords and ladies whose nameplates had been lost to time, and that blasted clock that went off at all hours.

“The King’s Club?” I asked. “I’ve seen their crest in the hallways at King’s College.”

“Aye,” he said, buttering his bread with a certain ferocity. “An association of university academics and other professionals in London. It’s been around for generations, claiming to contribute to charitable organizations—there’s an orphanage somewhere they fund.” He finished buttering his roll and took a healthy bite, closing his eyes to savor the taste. He swallowed it down with a sip of sherry.

“I was a member long ago, when I was young and foolish,” he continued. “That’s where I met your father. We soon found it nothing more than an excuse for aging old men to sit around posturing about politics and getting drunk on gin, and neither of us ever went back. Radcliffe’s a fool if he thinks they can woo me again.”

I smiled quietly. Sometimes, I was surprised the professor and I weren’t related by blood, because we seemed to share what I considered a healthy distrust of other people’s motives.

“What do you say?” he asked. “Would you like to make an appearance at the masquerade?” He gave that slightly crooked smile again.

“If you like.” I shifted again as the lace lining of my underskirt itched my bare legs like the devil. I’d never understand why the rich insisted on being so damned uncomfortable all the time.

“Good heavens, no.

I haven’t danced in twenty years. But Elizabeth should arrive by then, unless there’s more snow on the road from Inverness, and I’ve no doubt we shall be able to wrangle her into a ball gown. She used to be quite the elegant dancer, as I recall.”

The professor stowed his glasses in his vest pocket. Elizabeth was his niece, an educated woman in her mid-thirties who lived on their family estate in northern Scotland and served the surrounding rural area as a doctor—an occupation a woman would only be permitted to do in such a remote locale. I’d met her as a child, when she was barely older than I was now, and I remember beautiful blond hair that drove men wild, but a shrewdness that left them uneasy.

“You know how the holidays are,” he continued, “all these invitations to teas and concerts. I’d be a sorry escort for you.”

“I very much doubt that, Professor.”

While he went on talking about Elizabeth’s Christmas visit, I dug my fork beneath my dress and scratched my skin beneath the itchy fabric. It was a tiny bit of relief, and I tried to work it under my corset, when the professor cocked his head.

“Is something the matter?”

Guiltily, I slid the fork into my lap and sat straighter. “No, sir.”

“You seem uncomfortable.”

I looked into my lap, ashamed. He’d been so kind to take me in, the least I could do was try to be a proper lady. It surely wasn’t right that I felt more comfortable wrapped in a threadbare quilt in my attic workshop than in his grand townhouse. The professor didn’t know about the attic, and only knew a very limited account of what had happened to me over the past year. I had told him that the previous autumn I’d stumbled upon my family’s former servant, Montgomery, who had told me that my father was alive and living in banishment on an island, to which he took me. I’d lied to the professor and said Father was ill and passed away from tuberculosis. I had claimed that the disease had decimated the island’s native population and I’d fled, eventually making my way back to London.

I had said nothing of Father’s beast-men. Nothing of Father’s continued experimentation. Nothing of how I’d fallen in love with Montgomery and thought my affections returned, until he’d betrayed me. Nothing of Edward Prince, either, the castaway I’d befriended, only to learn he was Father’s most successful experiment, a young man created from a handful of animal parts chemically transmuted using human blood. A boy who had loved me despite the secret he kept carefully hidden, that a darker half—a Beast—lived within his skin and took control of his body at times, murdering the other beast-men who had once been such gentle souls. Edward was dead now, his body consumed in the same fire that had taken my father. That didn’t mean, however, that I’d ever managed to forget him.