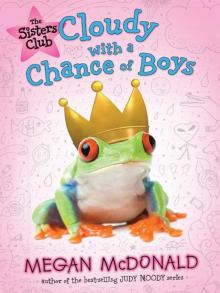

The Cloudy with a Chance of Boys

Megan McDonald

I used to think weather was boring.

Something old people talk about to fill an empty room with conversation. Just look at my nana and papa — they’re permanently tuned to the Weather Channel.

Weather was one of those things I never really paid attention to.

That was before.

Before the lights went out during the Storm of the Century. Before the frogs appeared. Before I got my first detention.

Before the tsunami.

But that comes later.

I guess you could say I have weather on the brain these days. We’re doing a serious weather unit in Earth Science, and I am like a semi–cloud expert now. I’ve spent a lot of time watching clouds from the third-story attic window of our crooked old Victorian. Some days I climb up Reindeer Hill to observe clouds and look for unusual cloud shapes. Then, I take pictures to document them. I’m making a cloud chart, which is like a mega-poster filled with cool photos of all kinds of clouds — cumulus, cirrus, stratonimbus.

At first, it was just a school project I had to do to get a decent grade. But the more I watched, the more I began to think clouds have . . . personalities. One minute they look like happy puffs of cotton candy — marshmallow castles in the air. Then you blink, and right before your eyes that same cloud has morphed into a snake or a dragon.

Come to think of it, clouds are like sisters. I should know. I have two of them — Alex, my older sister, and Joey, who’s two years younger than me.

Alex, I would have to say, is a thunderhead: dark and mysterious, quick to anger, as if there’s a storm gathering inside her. Joey is a cumulus: a happy cloud that comes out on a bright, blue-sky day and looks like a bunny wearing fuzzy bedroom slippers.

Me, I’m more of a cirrostratus, what the science book calls “uniform clouds, hardly discernible, capable of forming halos.” They look like light brushstrokes across the sky. You know, the even, steady kind. Always there, but sometimes you don’t even notice.

I never thought much about clouds, really, till now. Suddenly, they’re everywhere. In Shakespeare, Hamlet looks at clouds and compares them to a camel, then a weasel, not to mention a whale. In Language Arts, a poem we studied by e. e. cummings had a locomotive spouting violets, which I think must be clouds. There’s even a local chapter of the Cloud Appreciation Society, right here in Acton, Oregon. They have a logo and everything.

But the most important thing about clouds is that they give you a hint about what’s to come. All you have to do is see the signs. Read the sky.

Right after we started our weather unit, I noticed trees were leafing. Somewhere, frogs dreamed of hatching. Joey told me once that frogs can actually smell danger before they hatch. All I could smell was rain.

And then, for three days, we were under a mackerel sky — a sky filled with cirrocumulus and altocumulus clouds. Think buttermilk. Think thousands of tiny fish scales. A mackerel sky means three things: precipitation, instability, and thunderstorms.

So, for all I know about weather, you’d think I would have seen it coming. I should have known that something was about to happen. Something that would change me. Us. The sisters.

You can smell rain. You can hear thunder coming. But there’s not a weatherman on the planet who could have given me this forecast: cloudy, with a chance of boys.

One minute we were just talking and being sisters. The next minute, we were in the dark.

Here’s what happened. Alex, Medieval Fashion Designer, was stretched out on the floor, surrounded by twenty-seven thousand colored pencils scattered like Pick-up Sticks. She was designing a fancy costume for Juliet (“Romeo’s better half,” she says) instead of drawing a self-portrait for Art class.

Joey was making animal sculptures out of colored marshmallows. She found an old cookbook of Mom’s from the 1960s with marshmallow animals, and she’s working on a whole zoo, complete with lions, elephants, and giraffes.

I was way into pasting pictures of clouds on a giant three-fold poster board for Mr. Petry’s Earth Science class.

“Since when did the Sisters Club become the Homework Club?” I asked.

Just then, a giant boom of thunder shook the house. Rain pelted the windows, rattling them in their frames. A crack of lightning lit the room with an eerie flash.

“Wow. It’s a real weather freak show out there,” I said.

The lights flickered. On-off. On-off-on.

Alex looked up from her sketchbook.

“Uh-oh,” said Joey.

In a blink, the whole house went dark. We’re talking pitch-black, can’t-see-your-hand-in-front-of-you night.

Joey ran to get a flashlight, bouncing it off the walls like a light show. Ahh! She shined the light right in my face just to bug me.

“Okay, Duck,” I said, holding up my arm to shield my face.

Mom burst through the door, smelling of pine and mud and bark. “Wind’s really wicked out there,” she said, plunking down an armload of wood, her wild hair studded with wet leaves.

“Mom. Hair,” Alex pointed.

“You wouldn’t believe all the branches that have come down,” she said, pulling leaves from her hair. “Dad’s trying to clear the sidewalk. Power could be out for a while. I’m going to build up the fire. The heat may not come back on right away, so we better keep the fire going.”

“Just like Victorian times!” said Joey. Ever since Joey’s Little Women phase, she thinks old-timey stuff is way cool. Me, I like my electricity. Not to mention soap.

Mom poked at the logs in the fireplace until the fire blazed bright orange.

The back door blew open. Dad came in and set a flashlight on the counter, shaking rain from his hair like a dog after a bath. “Phew. It’s a real tempest out there.” Dad’s an actor and owns the Raven Theater next door. He’s always spouting Shakespeare and stuff.

Dad dried his sleeves and warmed his hands in front of the fire. Wind whistled down the chimney.

“‘Blow winds and crack your cheeks. Rage! Blow!’ You know, girls, in Shakespeare, when there’s a wild storm like this, like in King Lear, it means something big is about to happen.”

“Yeah, like murder!” I said. Joey clutched my arm.

“The storm can’t be all bad. Maybe something different and exciting is going to happen to us,” said Dad.

“Dad, you’re such a Drama Queen,” said Alex.

“Look who’s talking,” I said.

“I love storms,” said Joey.

“No, you love frogs,” I said.

“Duh. After a storm, millions of frogs come out.”

“Girls, help me with the candles,” said Mom.

Alex helped Mom light tea candles inside tuna fish cans. Spooky shadows like wolves and flying birds flickered across the walls.

“Let’s make hand shadows!” said Joey. “Like they did in Victorian times. I know how to make a swan.” Joey formed a beak with one hand and made feathers with the other.

“Well,” said Dad. “Time to go brave the elements again. A huge tree limb came down and fell across the back fence.” He shrugged on his already dripping-wet coat and headed out the back door.

“So, are you girls okay for now? I’ll check back in a while. I better help Dad with that branch if there’s any hope of saving the fence.”

“We’re okay,” I answered. “It’s all good.”

“Except for Alex stepped on my marshmallow giraffe,” said Joey, shining the flashlight on her smushed creation. “Now he looks like a headless weasel.”

“Did not,” said Alex. “How do you know it wasn’t Stevie?”

“Because,” I said, “she can tell it was your big old teenager feet.”

“Girls,” said Mom. “

I’m sure you can come up with something to do in the dark besides drive each other crazy. Stevie, keep the fire going, okay? And try to keep your sisters from squabbling.” She headed out the back door after Dad.

“Me? Why’s it always me?” I asked as soon as she was gone.

“Squabble, squabble,” said Alex, making turkey gobbling sounds, and we couldn’t help cracking up.

“Oh, well. I guess we’ll just have to eat this one.” Joey held up her headless weasel-giraffe with the broken neck.

“Ha. I don’t think so! Not after you licked every one of them,” said Alex.

“Not every one.”

“What ever happened to Jell-O?” I asked. “I thought you lived for Jell-O.”

“Jell-O’s cool. But, it’s just so third grade.” Alex cracked up.

“Check it out! Creck-eck. Creck-eck.” Joey made a hand-shadow frog on the wall. “Well, if you guys aren’t going to make hand shadows, let’s do something scary since the lights are out. Like tell scary stories,” she suggested.

A crack of thunder made Joey jump.

“You always want us to tell scary stories, Duck. Then you keep me up all night because you’re too scared to go to sleep or you have bad dreams.”

“We could have a séance,” said Joey. “Maybe there’s a ghost of a dead person who used to live in our house hundreds of years ago, and we could communicate with it.”

“How do you know about séances?” Alex asked.

“Victorian times,” Joey and I said at the exact same time.

“Jinx. You owe me a hot chocolate,” I said, punching Joey in the arm.

“I know. How about fortune-telling?” said Alex. “I went to this girl Mira’s fourteenth birthday party. Remember? It was a sleepover and we stayed up all night for the first time ever. Well, all except for this one girl, Alyssa.”

“Mira? Alyssa? Who are they?” I asked.

“Just some girls I know. Anyway — the really cool part was Mira’s mom hired this fortune-teller to read our palms. Check out my heart line.” She pointed to a line that creased her palm like a half-moon. “The fortune-teller said it means I’m very lovable.”

I peered at my palm in the candlelight. A map of glue was stuck to my hand. “What does it mean if your heart line is covered in glue?”

“It means you’re stuck up,” said Alex.

“Ha, ha. Very funny.”

“You guys,” said Joey. “Let’s roast marshmallows in the fire. Please? I have pink, blue, and green marshmallows. We can make rainbow s’mores!”

I was only half listening. I stared at the fire, hypnotized, peeling glue off my palm as if shedding an old skin. A small yellow flame licked the edges of a piece of kindling, then burst into a blaze. Orange fingers of fire flickered and danced, casting a spell on me.

Alex’s excited voice broke into my far-off daydream. “I got it, you guys,” said Alex. “I know what we can do. It’s perfect.”

“What?” Joey and I said at the same time again. But by the time I’d gotten done jinxing her, Alex had left and gone upstairs.

Alex came back waving one of her teen magazines at us and carrying a small box. Her eyes looked even greener than usual in the eerie glow of the flashlight.

“We don’t have to take one of your quizzes, do we?” I asked, trying to dig a splinter from my finger in the firelight.

“Some quizzes are cool,” said Joey.

“No, not a quiz. It’s this thing we were going to do at the sleepover, but you have to have a real fire. So tonight is perfect.”

I felt a shiver. The hairs on my arms stood up. This was going to be good.

“Joey, hold the flashlight. Okay, it’s right here on page fifty-seven,” said Alex, squinting to see.

Joey looked over her shoulder and read the headline. “How to Get Noticed by a Boy?” She said it like a question. “No way!” she protested. “I’m not putting gunk on my face. And I’m not putting curlers in my hair. And I’m definitely not brushing on any shadows to make my nose look smaller, because — guess what? — not every girl in the world has nose envy!”

“Chill out, Stressarella. No makeup. Honest.” Alex held up her hand like she was taking a solemn oath. “It’s cool. See, you follow the directions, it tells you right here —”

“But Stevie and I don’t care about boys, do we, Stevie?” Joey gave me a look that pleaded, Back me up, here.

I looked down at my palm. I didn’t answer. I went back to working on the splinter in my finger. It’s not like I’m boy crazy or anything — not like Olivia and half the girls in my grade. But I was a little curious to hear what Alex had to say.

“It doesn’t have to be about boys,” said Alex. “It can be about anything. It’s just a way to make something happen that you want to come true. Like a wish,” she said to Joey.

“You mean like a magic spell?” asked Joey.

“Um . . . sure,” said Alex. “It’ll be like the three witches in Macbeth.”

“Can’t we just wish on a wishbone like normal people?” said Joey.

“BORing,” said Alex, imitating Joey.

“Okay, but I’m only doing it if we get to say ‘eye of newt’ and stuff,” Joey said.

“Sure!” said Alex. “Then we get to throw stuff in the fire! It’ll be cool, right, Stevie?”

“I guess,” I said. There had been a momentary calm, but now the angry storm was picking up outside again. “As long as we don’t have to burn our fingernail clippings or anything creepy like that. And you’re not getting a lock of my hair, or my baby tooth. And no blood. And definitely no dancing around in our underwear!”

“Same here,” said Joey. “All that stuff Stevie said.”

“Nothing like that, you guys. But I do have some incense we can burn. Winterforest Dewberry or Cherry Manlove?”

“Is that really what they’re called?” I asked, taking the box from Alex and holding it up to my nose. “Uck. They both smell like wet dog hair.”

“Cherry, cherry, cherry, cherry, cherry,” Joey chanted. I guess she didn’t hear the “manlove” part.

“Cherry it is,” said Alex. “And we already have candles and a fire.”

When had my sister the Drama Queen turned into a Pyro Queen? Alex Reel, Pyromaniac, at your service.

“Step one. First we have to close our eyes and take three deep breaths,” Alex instructed us. “Concentrate. Focus. Think of something you want to happen. Then picture it in your mind’s eye.”

I closed my eyes. Something I would like to happen? Have an extra-cheese pizza appear before me. Get an A on my Earth Science project. Not have to clean my room.

“Can it be something we don’t want to happen?” I asked.

“Shh,” said Alex.

If I had one wish, what would it be? To have the lights come back on so I don’t have to do this? I wish . . . I wish . . . why can’t I think of anything to wish? I wish my hair would grow . . . Lame-o. Think, Stevie, think.

A low rumble of thunder sent a chill through me, raising the hair on my arms. “Open your eyes,” said Alex in a spooky voice. She read from the magazine again. “Step two. Keeping the person in mind, think of an object related to that person. Choose something close to your heart that has special meaning. Step three. Say the magic words, close your eyes, and toss your Special Object into the fire.”

“Person? What person?” Joey asked. “You mean a boy? You said it wasn’t about boys. You so lie.”

“It just means — never mind. I forgot we’re not doing the boy thing. So think of the thing you wish to happen, and pick an object to throw in the fire. But it has to be something you like a lot. Something personal. Something that’s hard to give up. Otherwise it won’t work.”

“Says who?”

“Says step number three, right here.” Alex jabbed the magazine with her finger. “You guys take the other flashlight. Let’s go find our good luck charms.”

“But I don’t have a wish!” I called after Alex, but she was alre

ady headed for the stairs.

Joey and I climbed the stairs behind Alex. Alex went straight to her room and came back with an old shoebox full of baby stuff and mementos. In no time, Joey was ready too.

But I bounced the beam around our room, looking for something, anything, to throw into the fire. An old journal, a cooking contest ribbon, a cupcake candle I got in my Christmas stocking? School picture? A picture of Act Two, our old dog? My last report card? Friendship bracelet from Olivia? It was kind of hard to choose, since I really didn’t know what to wish.

In the distance, I could hear an emergency siren.

Then, in the beam of my flashlight, I caught sight of a troll doll with neon-green hair and a diamond in its belly, giving me the evil eye.

Perfect! Mom once told me that trolls were supposed to be good luck. I grabbed the troll doll by its green hair. Who didn’t want to wish for good luck?

We crept back downstairs and all three of us crouched in front of the fire.

“Alex, what did you pick?” Joey asked eagerly.

“Um . . . it’s a secret,” said Alex. “You’re not supposed to tell, or show your Special Object to anybody. Keep it in your pocket or behind your back till we’re ready.”

“What magic words should we say?” Joey asked.

“How about if I say the ‘Double, double, toil and trouble’ part, then you guys answer, ‘By the pricking of my thumbs / Something wicked this way comes.’”

Branches scratched against the window like fingernails on a chalkboard. I felt a shiver up my back.

“Too creepy,” Joey said.

“Okay . . .” said Alex, in a thin voice. “How about, ‘Come you spirits, make my blood thick —’”

“No blood!” I reminded Alex.

“C’mon, you guys. You’re wrecking the mood.”

“Yeah, Joey, stop wrecking the mood,” I teased. I wiggled my troll doll in her face to spook her.

“Hey, she showed us her Special Object. You’re not supposed to show us your Special Object,” said Joey. “Do you think the magic will still work, Alex?”

“It’ll work,” Alex said. “Okay, you guys. Be serious. This is it. Close your eyes. I’m going to say something in Shakespeare, and you can’t fight me on it. Then I’ll count to three. On the count of three, open your eyes, and we each toss our Special Objects into the fire at the same time. Ready? Remember, the most important part is you have to believe.”