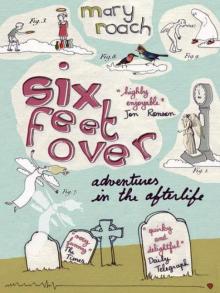

Six Feet Over: Adventures in the Afterlife

Mary Roach

FOR MY PARENTS,

WHEREVER THEY ARE OR AREN’T

Contents

Introduction

1. You Again

A visit to the reincarnation nation

2. The Little Man Inside the Sperm, or Possibly the Big Toe

Hunting the soul with microscopes and scalpels

3. How to Weigh a Soul

What happens when a man (or a mouse, or a leech) dies on a scale

4. The Vienna Sausage Affair

And other dubious highlights of the ongoing effort to see the soul

5. Hard to Swallow

The giddy, revolting heyday of ectoplasm

6. The Large Claims of the Medium

Reaching out to the dead in a University of Arizona lab

7. Soul in a Dunce Cap

The author enrolls in medium school

8. Can You Hear Me Now?

Telecommunicating with the dead

9. Inside the Haunt Box

Can electromagnetic fields make you hallucinate?

10. Listening to Casper

A psychoacoustics expert sets up camp in England’s haunted spots

11. Chaffin v. the Dead Guy in the Overcoat

In which the law finds for a ghost, and the author calls in an expert witness

12. Six Feet Over

A computer stands by on an operating room ceiling, awaiting near-death experiencers

Last Words

Acknowledgments

Bibliography

Introduction

MY MOTHER worked hard to instill faith in me. She sent me to catechism classes. She bought me nun paper dolls, as though the meager fun of swapping a Carmelite wimple for a Benedictine chest bib might inspire a taste for devotion. Most memorably, she read me the Bible. Every night at bedtime, she’d plow through a chapter or two, handing over the book at appropriate moments to show me the color reproductions of parables and miracles. The crumbling walls of Jericho. Jesus walking atop stormy seas with palms upturned. The raising of Lazarus—depicted in my mother’s Bible as a sort of Boris Karloff knockoff, wrapped in mummy’s rags and rising stiffly from the waist. I could not believe these things had happened, because another god, the god who wore lab glasses and knew how to use a slide rule, wanted to know how, scientifically speaking, these things could be possible. Faith did not take, because science kept putting it on the spot. Did the horns make the walls fall, or did there happen to be an earthquake while the priests were trumpeting? Was it possible Jesus was making use of an offshore atoll, the tops of which sometimes lie just inches below the water’s surface? Was Lazarus a simple case of premature entombment? I wasn’t saying these things didn’t happen. I was just saying I’d feel better with some proof.

Of course, science doesn’t dependably deliver truths. It is as fallible as the men and women who undertake it. Science has the answer to every question that can be asked. However, science reserves the right to change that answer should additional data become available. Science first betrayed me in the early eighties, when I learned that brontosaurus had lived in a sere, rocky desert setting. The junior science books of my childhood had shown brontosaurs hip-deep in brackish waters, swamp greens dangling from the sides of their mouths. They’d shown tyrannosaurs standing erect as socialites and lumbering Godzilla-slow, when in reality, we were later told, they had sprinted like roadrunners, back flat and tail aloft. Science has had us buying into the therapeutic benefits of bloodletting, of treating melancholy with arsenic and epilepsy with goose droppings. It’s not all that much different today: Hormone replacement therapy went from miracle to scourge literally overnight. Fats wore the Demon Nutrient mantle for fifteen years, then without warning passed it to carbohydrates. I used to write a short column called “Second Opinion,” for which I scanned the medical literature, looking for studies that documented, say, the health benefits of charred meat or the deleterious effects of aloe on wound-healing. It was never hard to fill it.

Flawed as it is, science remains the most solid god I’ve got. And so I decided to turn to it, to see what it had to say on the topic of life after death. Because I know what religion says, and it perplexes me. It doesn’t deliver a single, coherent, scientifically sensible or provable scenario. Religion says that your soul goes to heaven or possibly to a seven-tiered garden, or that your soul is reincarnated into a new body, or that you lie around in your coffin clothes until the Second Coming. And, of course, only one of these can be true. Which means that for millions of people, religion will turn out to have been a bum steer as regards the hereafter. Science seemed the better bet.

For the most part, science has this to say: Yeah, right. If there were a soul, an etheric disembodied you that can live on, independent of your brain, we scientists would know about it. In the words of the late Francis Crick, codiscoverer of the structure of DNA and author of The Astonishing Hypothesis: The Scientific Search for the Soul, “You, your joys and your sorrows, your memories and your ambitions, your sense of personal identity and free will, are in fact no more than the behavior of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules.”

But can you prove that, Dr. Crick? If not, then it’s no more good to me than the proclamations of God in the Old Testament. It’s just the opinion, however learned, of one more white-haired, all-knowing geezer. What I’m after is proof. Or evidence, anyway—evidence that some form of disembodied consciousness persists when the body closes up shop. Or doesn’t persist.

Proof is a tremendously comforting thing. When I was little, I used to worry that one day, without warning, the invisible forces that held me to the earth were going to conk out, and that I would drift up into space like a party balloon, rising and rising until I froze or exploded or suffocated or all three at once. Then I learned about gravity, the dependable pull of the very large upon the very small. I learned that it had been scientifically proven to exist, and I no longer worried about floating away. I worried instead about blackheads and whether Pat Stone dreamed of me and other dilemmas for which science could provide no succor.

It would be especially comforting to believe that I have the answer to the question, What happens when we die? Does the light just go out and that’s that—the million-year nap? Or will some part of my personality, my me-ness, persist? What will that feel like? What will I do all day? Is there a place to plug in my laptop?

Most of the projects that I will be covering have been—or are being—undertaken by science. By that I mean people doing research using scientific methods, preferably at respected universities or institutions. Technology gets a shot, as does the law. I’m not interested in philosophical debates on the soul (probably because I can’t understand them). Nor am I going to be relating anecdotal accounts of personal spiritual experiences. Anecdotes are interesting, occasionally riveting, but never are they proof. On the other hand, this is not a debunking book. Skeptics and debunkers provide a needed service in this area, but their work more or less assumes an outcome. I’m trying hard not to make assumptions, not to have an agenda.

Simply put, this is a book for people who would like very much to believe in a soul and in an afterlife for it to hang around in, but who have trouble accepting these things on faith. It’s a giggly, random, utterly earthbound assault on our most ponderous unanswered question. It’s spirituality treated like crop science. If you found this book in the New Age section of your local bookstore, it was grossly misshelved, and you should put it down at once. If you found it while browsing Gardening, or Boats & Ships, it was also misshelved, but you might enjoy it anyway.

AUGUST 6, 1978, was a Sunday, the Feast of the Transfiguration. It was evening, and Pope Paul VI

lay dying in his bedroom. With him was his doctor and two of his secretaries, Monsignor Pasquale Macchi and Father John Magee. At 9:40 p.m., following a massive heart attack, His Holiness expired. At that very moment, the alarm clock on his bedside table rang out. Accounts of this episode refer to the timepiece as the Pope’s “beloved Polish alarm clock.” He bought it in Warsaw in 1924 and carried it with him in his travels from then on. He seemed to be fond of it in the way that farmers are fond of old, slow- moving dogs, or children of their blankets. Every day, including the day he died, the alarm was set for 6:30 a.m.

I first came upon this story in a gullible and breathless compilation of supposed evidence for the afterlife. I don’t recall the book’s title (though the title of the chapter about spirit communication—“Intercourse with the Dead”—seems to have stayed with me). The book presented the story of the pontiff ’s noisy passing as proof that some vestige of His Holiness’s spirit influenced the papal clockworks* as it departed the body. Pontiff, a popular biography of Paul VI, relates the tale with similar cheesy dramatics: “At that precise moment the ancient alarm clock, which had rung at six thirty that morning and which had not been rewound or reset, begins to shrill….”

In Peter Hebblethwaite’s Paul VI: The First Modern Pope we find a different take on the proceedings. In the morning of his last day, the Pope is sleeping. He awakes and asks the time and is told it’s 11 a.m. “Paul opens his eyes and looks at his Polish alarm clock: it shows 10:45. ‘Look,’ he says, ‘my little old clock is as tired as me.’ Macchi tries to wind it up but confuses the alarm with the winder.” By this version, the alarm went off at the moment the Pope died because Monsignor Macchi had accidentally set it for that moment.

I am inclined to side with Hebblethwaite, because (a) his book is studiously footnoted and (b) Hebblethwaite doesn’t gild his renderings of papal life. For instance, we have the scene in the final chapter wherein Pope Paul VI is lying in bed watching TV. Not only is the earth’s highest-ranking Catholic, the Holy of Holies, watching a B-grade western, he is having trouble following it. Hebblethwaite quotes Father Magee, who was there at the time: “Paul VI did not understand anything about the plot, and he asked me every so often, ‘Who is the good guy? Who is the bad guy?’ He became enthusiastic only when there were scenes of horses.” Hebblethwaite tells it like it is.

Just to be certain, I decided to track down the man who either did or didn’t mess with the winder: Pasquale Macchi. I called up the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, the American mouthpiece of the Catholic Church, and was put through to the organization’s then librarian, Anne LeVeque. Anne is an accommodating wellspring of Catholic-related trivia, including the stupendously odd fact that freshly dead popes are struck thrice on the forehead with a special silver hammer. LeVeque knew someone in the organization who had spoken with a group of priests who had met with Macchi shortly after Paul VI’s death, and she gave me his number. He agreed to tell me the story, but he would not reveal his name. “I’m better as your Deep Throat,” he said, forever linking in my head the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops with porn movies, a link they really and truly don’t need.

Deep Throat confirmed the basic story. “It was described to me as not instantaneous, but more of a five, four, three, two, one … and the alarm went off.” He was told that despite what others had said, the clock had not been set for the time at which Paul died. “The feeling,” he said, “was that what it suggested was the departure of Paul VI’s soul from his body.” Then he looked up Macchi’s address for me, in what he called the Pontifical Phone Book. I wanted to ask if it included a Pontifical Yellow Pages, with pontifical upholstery cleaners and pontifical escort services, but managed not to.

Macchi is a retired archbishop now. With the help of a friend’s friend from Italy, I drafted a note asking about the alarm clock incident. Archbishop Macchi wrote back promptly and courteously, addressing me as “Gentle Scholar,” despite my having addressed him as Your Eminence (suggesting mere cardinalhood) when in fact he is either a Your Excellency or a Your Grace, depending on whose etiquette book you consult. (Your Holiness, reserved for the Pope himself, trumps all, except possibly, in my hometown anyway, Your San Francisco Giants.) Macchi included a copy of his own biography of Paul VI, with a bookmark at page 363. “In the morning of that day,” he wrote, “having noticed that the clock was stopped, I wanted to wind it up and inadvertently I had moved the alarm hand setting to 9:40 p.m.” Deep Throat’s deep throats, it seems, had led him astray.

Annoyingly, I came across yet a third version of the alarm clock incident, this one by a priest with a grudge against Paul VI. This man held that the clock story had been fabricated by the Vatican as evidence for a false time of death, part of an effort to cover up some breach of papal duty that would have made the Pope seem impious.

The moral of the story is that proof is an elusive quarry, and all the more so when you are trying to prove an intangible. Even had I managed to establish that the alarm clock had indeed gone off for no obvious mechanical reason at the moment the pontiff died, it wouldn’t have proved that his departing soul had triggered it. But I couldn’t even get the clock to stand and deliver.

The deeper you investigate a topic like this, the harder it becomes to stand on unshifting ground. In my experience, the most staunchly held views are based on ignorance or accepted dogma, not carefully considered accumulations of facts. The more you expose the intricacies and realities of the situation, the less clear-cut things become.

And also, I hold, the more interesting. Will I find the evidence I’m looking for? We’ll just see. But I promise you a diverting journey, wherever it is we end up.

*A modern corollary to the Pope’s alarm clock can be found in the erratic behavior of a digital alarm clock belonging to a Mrs. Linda G. Russek, of Boca Raton, Florida. Russek’s husband Henry had recently died, and she wondered whether he was trying to communicate with her via the clock. Russek, a parapsychologist, undertook an experiment in which she asked Henry to speed the clock up on even days and slow it down on odd days. Alas, the data were meaningless because shortly after the study began, the AM/PM indicator had gone on the blink, and Russek was unable to definitively conclude anything beyond the fact that she needed a new alarm clock.

Six Feet Over

1

You Again

A visit to the reincarnation nation

I DON’T RECALL my mood the morning I was born, but I imagine I felt a bit out of sorts. Nothing I looked at was familiar. People were staring at me and making odd sounds and wearing incomprehensible items. Everything seemed too loud, and nothing made the slightest amount of sense.

This is more or less how I feel right now. My life as a comfortable, middle-class American ended two nights ago at Indira Gandhi International Airport. Today I am reborn: the clueless, flailing thing who cannot navigate a meal or figure out the bathrooms.

I am in India spending a week in the field with Kirti S. Rawat, director of the International Centre for Survival (as in survival of the soul) and Reincarnation Researches. Dr. Rawat is a retired philosophy professor from the University of Rajasthan, and one of a handful of academics who think of reincarnation as something beyond the realm of metaphor and religious precept. These six or seven researchers take seriously the claims of small children who talk about people and events from a previous life. They travel to the child’s home—both in this life and, when possible, the alleged past life—interview family members and witnesses, catalogue the evidence and the discrepancies, and generally try to get a grip on the phenomenon. For their trouble, they are at best ignored by the scientific community and, at worst, pilloried.

I would have been inclined more toward the latter, had my introduction to the field not been in the form of a journal article by an American M.D. named Ian Stevenson. Stevenson has investigated some eight hundred cases over the past thirty years, during which time he served as a tenured professor at the University of Virginia and a contributor to peer-re

viewed publications such as JAMA and Psychological Reports. The University of Virginia Press has published four volumes of Stevenson’s reincarnation case studies and the academic publisher Praeger recently put out Stevenson’s two-thousand-word opus Biology and Reincarnation. I was seduced both by the man’s credentials and by the magnitude of his output. If Ian Stevenson thinks the transmigration of the soul is worth investigating, I thought, then perhaps there’s something afoot.

Stevenson is in his eighties and rarely does fieldwork now. When I contacted him, he referred me to a colleague in Bangalore, India, but warned me that she would not agree to anything without meeting me in person first—presumably in Bangalore, which is a hell of a long way to go for a get-acquainted chat. A series of unreturned e-mails seemed to confirm this fact. At around the same time, I had e-mailed Kirti Rawat, whom Stevenson worked with on many of his Indian cases in the 1970s. Dr. Rawat happened to be in California, an hour’s drive from me, visiting his son and daughter-in-law. I drove down and had coffee with the family. We had a lovely time, and Dr. Rawat and I agreed to get together in India for a week or two while he investigated whatever case next presented itself.

The Kirti Rawat who met me at the airport was in a less contented state. He had been arguing with management over the room service at the hotel where I had booked us. The next morning, we packed up our bags and moved across Delhi to the Hotel Alka (“The Best Alternative to Luxury”), where he and Stevenson used to stay. The carpets are clammy, and the toilet seat slaps you on the rear as you get up. The elevator is the size of a telephone booth. But Dr. Rawat likes the vegetarian dinners, and the service is attentive to the point of preposterousness. Bellhops in glittery jackets and curly-uppy-toed slippers flank the front doors, opening them wide as we pass, as though we’re foreign dignitaries or Paris Hilton on a shopping break.