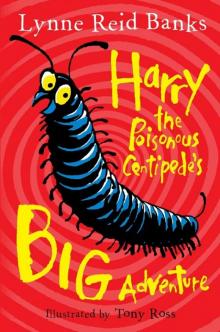

Harry the Poisonous Centipede's Big Adventure: Another Story to Make You Squirm

Lynne Reid Banks

To Dnl Stphnsn

(and his prnts)

Table of Contents

Title Page

Dedication

1. Caught

2. The Hard-Air Prison

3. The Collection

4. Captivity

5. Crash!

6. The Big Prison-Break

7. Flying Through Space

8. The No-End Puddle

9. To Eat – or Be Eaten

10. The Rescue

11. The hunt

12. The Battle

13. Sink or Swim

14. A Short Chapter with a Surprise at the End

15. The Long March Begins

16. The Worst Things in the World

17. An Old Enemy

18. An Old Friend

19. The Dung-Ball Track

20. Wanted-for Squashing

21. Who Goes There?

Also by the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

1. Caught

Harry was bored.

This is not something that happens often to a poisonous centipede. Harry was generally very busy about something or other. Chasing things like beetles, ants and worms, biting them with his poison pincers, and eating them; running away from bigger things like snakes and rats trying to eat him; exploring in the tunnels; playing with George, his best friend; or just being at home in his nest-tunnel with his mother, Belinda.

As perhaps you know, Harry was not his real, Centipedish name. This was (are you ready for this?) Hxzltl. And George’s was Grnddjl. And Belinda’s was Bkvlbbchk. They’re hard to say. But then, so is any word, if you leave the vowel-sounds out.

Try it with your own name. Bet you can’t say it in Centipedish so anyone would recognise it. I mean, say your name is Daniel, in Centipedish (which leaves out the a’s, e’s, i’s, o’s and u’s) it would be Dnl. If your name’s Rebecca, it would be Rbcc. If your name begins with a vowel, say Anna or Ursula or Oscar, it’s even worse – I mean, how could you say Nn or Rsl or Scr?

But that’s the way centipedes talk to each other – well, I say “talk”, it’s more of a crackle. Too faint for human ears to hear. Often they just signal with their feelers. That’s why they’re rather strange, secretive, mysterious creatures.

You’re really lucky to have me to tell you about them.

Where was I? Oh yes. Harry. Being bored for once.

He’d spent the early part of the night, since he woke up, helping his mother in their nest-tunnel. He’d straightened out his leaf-bed and rubbed his head on the earth floor to polish it.

Then Belinda had brought home a stag beetle for their breakfast and he had helped her get its massive jaws and its hard carapace off and had hauled them out to their rubbish tip tunnel. Then, while they ate, he asked for a story and his mother told him one about a family of marine centipedes.

“Once upon a time, beside the great no-end puddle, there lived a family of centipedes that could swim.”

The stories always began like that. Harry loved them. He thought marine centipedes – his distant cousins – were brll, not to say cl and wckd. But she cut the story short at the most exciting part, because she thought she heard something interesting bumping about on the no-top-world over their heads, and scuttled off to investigate it.

That left Harry, tummy full of stag beetle, not feeling like moving much, wanting to know the end of the story – and missing George. Who was missing.

I mean, he’d disappeared. This was not unusual. George was a free spirit. He didn’t have a mother (though he borrowed Belinda when he was lonely or hungry). No one to keep tabs on him and stop him doing silly or dangerous things.

So quite often, he went off and had an adventure on his own. Then he was sometimes gone for nights. Harry and George were getting to be big centis now (a centi is a child centipede). A bit like teenagers. So Belinda couldn’t keep control the way she used to.

Harry lay on the floor of the nest-tunnel. He stretched himself to his full length, which was now about five inches. All his segments (he had twenty-one, with a pair of legs on each, forty-two legs altogether) felt lazy. And yet in Harry’s head was an urge to go somewhere, do something, have an adventure. Only, what?

He let himself play with the idea of going along the forbidden tunnel and Up the Up-Pipe into the Place of Hoo-Mins. He and George had done that once, when the white-choke (which was smoke) had driven them out of their usual tunnels and they had had to climb into the Hoo-Min’s home, up his drainpipe, and very nearly never came back again.

But no. That was too scary. Harry had a healthy fear of Hoo-Mins. Whenever he heard the vibrations of their great feet thudding overhead in the no-top-world, Harry cowered down or ran to hide (even though no Hoo-Min could see him down in the tunnels). George, when he was there, laughed at him and called him sissyfeelers, but Harry couldn’t help it.

His father had been killed by a Hoo-Min. So you can understand it. Even if Hoo-Mins had not been the biggest, fastest, weirdest, scariest things around.

“Walking about on two legs like that,” crackled Harry to himself. “It’s not natural. They’re not like anything else. They’re not like hairy-biters or belly-crawlers or flying-swoopers. They don’t belong.”

He had the vague idea that maybe they’d come from some other world. Not that he had any idea about planets and things like that. With his little weak eye-clusters he’d never even seen the stars. He just felt certain that Hoo-Mins were not part of the proper order of things.

They were just too much.

After a while, when Belinda didn’t come back, Harry gave a centipedish sigh (which he did by making a ripple go all along his back where his breathing-holes were) and got to his forty-two feet. He wandered up the nearest tunnel and when he got to the end, poked his head idly out into the night air of the no-top-world.

If he hadn’t been feeling rather dopey and full of food, he might have sensed something wrong and ducked back down again. But he didn’t. The darkness was sweet-smelling and the noises were all the ones he was used to – the faint sighing of palm fronds rubbing together, the rustle of little night-creatures skittering about. Not even a night-bird’s cry alerted him to danger.

He crawled forward until half of him was outside the hole.

Suddenly the most awful thing happened.

Something tightened around his middle!

He almost jumped into the air with fright. He instinctively turned and tried to run back down the tunnel. But he couldn’t. Something was holding him. Something was dragging him! SOMETHING WAS LIFTING HIM INTO THE AIR! He threshed all his legs frantically. He twisted his head and closed his poison-pincers again and again, trying to bite.

But there was nothing to bite. Only air.

The thing that had caught him was a loop of strong thread. It had been laid around the mouth of his exit tunnel. When he came out, the thread had been pulled sharply. The loop had tightened around him, between his tenth and his eleventh segments. Now he was dangling in midair on the end of the thread.

He was so frightened he didn’t even try to see what had caught him. He felt himself twirling, first in one direction, then back again in the other. High above the ground. If centipedes could be sick, Harry would have thrown up.

Then he felt himself moving through the air. He was being carried on the end of the thread, but he didn’t know that. All he knew was that never, since he had nearly drowned, had he felt so helpless and doomed.

“I’ve been picked up by a flying-swoope

r!” he thought despairingly. “I’m done for! Oh, Mama!”

But there was no Belinda to come to his rescue.

2. The Hard-Air Prison

Harry was carried, dangling and twisting, for some distance. Then there was a change.

Harry was used to the dark. He lived underground, and he was a night-creature, so he liked darkness.

And, except for that one time when he had been in a Hoo-Min’s home, he had never been indoors. But that one time had made such an impression that when the sudden brightness came, and the smells all changed, and the natural night-noises stopped, Harry knew immediately that he was once again in a Place of Hoo-Mins.

The most frightening place in the world.

He heard terrible, loud, un-understandable noises. They were Hoo-Mins’ voices, but he didn’t know that. He just knew he’d never heard anything like them. They were so loud they hurt his ear-holes.

Of course he couldn’t know what they were saying. But you can know, because I’ll tell you.

A little boy’s voice said, “Look, Dad! I got another one!”

And a man’s voice said, “Good for you, son! I told you you’d catch one with the thread if you were patient.”

“Is there a spare jar?”

“Yes. Your mother washed out a big pickle-jar. Put him in here.”

And Harry felt himself going down. Down and down. But when his forty-two feet touched something, it wasn’t lovely friendly soft earth. It was something hard and cold.

The loop was still round his middle. It was tight. It hurt him and scared him. But then there was a snapping sound and he felt the pull of the loop go slack. It was still there, around him, but at least it wasn’t pulling any more.

The thread had been cut.

He tried to flee. He thought he could escape because he couldn’t see anything in his way. But as he ran forward, he banged his head.

He turned and ran the other way. After a very few steps, he banged his head again!

He turned sideways and ran. He found he was running in a circle. Every time he tried to turn out of it, he bumped into something – something he couldn’t see.

He stopped, and touched the barrier with his feelers. It was weird. He could feel it but he couldn’t see it. It was under him and all around him. It was like hard air.

He tried to climb it but it was too slippery. His little claw-feet couldn’t get a grip on it. He slid back.

“He can’t get out of there,” said the man. “But put the lid on just in case. I’ve punched a hole in it so he can breathe.”

The little boy said happily, “I’ve got two centipedes in my collection now!”

A shadow fell on Harry, down in the bottom of the hard-air place. It was the lid going on, but he didn’t know that. He crouched down till his tummy touched the cold stuff.

Harry had never heard a Hoo-Min talk before. But he began to guess that was what was happening. He could see them now, two of them, a big one – huge, enormous, vast, gigantic, the biggest live thing he’d ever seen – and a not-so-big one which was still huge, enormous, vast and gigantic to Harry. He was terrified. If he could have understood their speech he would have been even more terrified than he was.

A great big horrible face appeared on the other side of the hard-air wall. Harry turned his back so as not to see it.

The big man said, “Now you take care he doesn’t get out. And don’t dream of touching him. They’re very dangerous. He’s a nice big one, though, isn’t he? Not as big as the one that bit me, though! That was twice his size.”

The man didn’t realise he was talking about Harry’s mother!

“I hate the things!” the man went on with a shudder. “Take him to your room, quick, before I tip him on the floor and squash him to a pulp!”

“I think he’s great,” said the boy. “Almost as good as my yellow scorpion.”

“You know what your mother thinks about all those creepy-crawlies in the house. Just don’t let him out of the jar.”

“Of course I won’t,” said the boy scornfully.

Then Harry saw a big pinky-brown THING wrap itself around the hard-air place. He looked down, and his weak little eyes could see the ground (it was a table, actually) sinking far away below him as the boy picked up the jar. It was awful, because Harry felt as if there were nothing underneath him to stop him falling.

He knew – he knew for certain – he was going to get his wish for a major adventure. And he wished with all his little centipedish heart that he was safely back in his home-tunnel.

3. The Collection

Harry in his pickle-jar was carried along for a short way and then he felt a jolt and saw that there was something solid underneath the floor of the hard-air place. He lost his head and started trying to escape again, running round and round inside the jar. It was useless, of course.

Suddenly he stopped. He’d caught a signal!

Insects and other small creeping creatures can’t speak to each other across the species, but they can make crude signals. I mean, one kind of creature can tell from another’s behaviour if there’s danger, for instance.

Now Harry stopped helplessly running around, and looked through the clear wall. Not far away from him was another hard-air prison. And in it was something he recognised.

He recognised it because it was very like what he’d eaten for breakfast.

It was a beetle, a large one. Not a stag beetle. A dung beetle, a female. Dung beetles are only happy when they have a ball of dung to roll along. This dung beetle didn’t. She had some earth in the bottom of her prison but it wasn’t dung, and she hadn’t the heart to roll it into a ball. Anyway, there was nowhere to roll it to.

She just sat forlornly with her six legs bent and her large head lowered. She looked to Harry like two things at once: a sad lady beetle and a good meal. He didn’t know which came first, but as he was still quite full of one of her distant relations, he decided to treat her as a fellow prisoner.

It was she who’d signalled to him. The signal said something like, “This is bad and I am sad.” (Beetles talk, and signal, in Beetle, a language that always rhymes. Of course Harry didn’t grasp this, just the general meaning – I’ve translated from Beetle as best I can.)

Harry signalled back, “Same here.”

She swayed her head from side to side. Then she moved forward and raised herself clumsily and put her front feet on the hard-air. This said, as clearly as words, “There is no doubt, I can’t get out.”

Harry rose up against the wall nearest to her, putting his front eight pairs of feet against it. “Me neither.”

The lady dung beetle swung her head in a wider arc. “None of us can. Have you a plan?”

Harry looked around. And got another shock.

There were lots of prisons made of the hard-air stuff! Harry couldn’t count, but if he could, he would have counted ten or twelve glass jars on the table where his was. Each one contained a prisoner.

There was a yellow scorpion, nearly as large as Harry, with pincers a lot larger (though his poison was in his tail, just now lying dejectedly behind him). There was a rhinoceros beetle, his big curved horn resting against the prison wall.

There were several caterpillars of different sizes and colours. There were two or three millipedes, a large, hairy tarantula, and several smaller spiders. There was a stick insect, which looked very unhappy indeed – it could hardly stand up straight, and besides, it didn’t have any sticks to hide amongst. Harry looked at all of them and took in their signals. All of the signals were sad and frightened.

And then he stiffened. Down at the far end, there was another centipede!

If centipedes could gasp, Harry would have gasped when he saw him.

It was George!

“Grndd! Grndd!” Harry crackled. But his crackle didn’t go through the hard-air.

Harry began to run around his prison frantically sending signals. The movement attracted the attention of all the prisoners. The ones who were lying on the

floor of their jars, some sleeping, some just slumped in despair, stood up and turned his way. His turns, his twists, his liftings and scrabblings of his front feet on the wall, made all the others think something was up.

A sort of current, or wordless message, passed from jar to jar. The dung beetle passed it to the scorpion, who passed it with a curving of his poison-tail to the rhinoceros beetle, who bumped his horn against the glass with a loud click, alerting the caterpillars, who wrigglingly passed it to the tarantula.

She hugged the air with her furry front legs urgently. This passed the message to the other spiders in their own language, and their scuttlings and jumpings passed it to the stick insect.

He was so depressed he couldn’t be bothered to pass it on, but by that time it didn’t matter. George had already grasped the fact that someone was trying to signal to him. He peered through his own glass wall and, though it was far away, he could just about make out some centipedish movements, which he recognised at once as Harry’s.

(Centipedes might look all alike to you, but believe me, they can tell each other apart as easily as you can tell your mother from your worst enemy at school.)

“Hx! Hx! They got you, too! Hx, we’ve got to get out!” signalled George, twisting and turning frenziedly.

Harry picked this up with some difficulty and stood still. He thought about it for a moment and then, slowly and deliberately, he sent this signal:

“Can you tunnel through this hard-air stuff?”

George signalled: “No, and nor can any of the others. There was a mole cricket here before, and he couldn’t.” The centis knew all about mole crickets. They were among the best tunnel-diggers in the earth.

“What happened to him?”

George lowered his head and sent a brief signal.

“Stopped.”

No creature likes to think about death. They all have words for it that soften its meaning, the way we say “passed away”. But Harry had to ask.