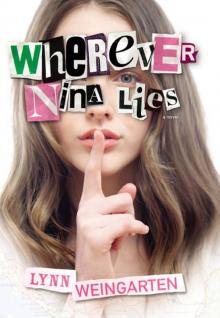

Wherever Nina Lies

Lynn Weingarten

Wherever Nina Lies

Lynn Weingarten

To sisters who love each other no matter what

Table of Contents

Title Page

Dedication

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-one

Twenty-two

Twenty-three

Twenty-four

Twenty-five

Twenty-six

Twenty-seven

Twenty-eight

Twenty-nine

Thirty

Thirty-one

Thirty-two

Thirty-three

Thirty-four

Thirty-five

Thirty-six

Thirty-seven

Thirty-eight

Thirty-nine

Forty

Forty-one

Forty-two

Forty-three

Forty-four

Forty-five

Acknowledgments

Copyright

One

The guy walking toward me is good-looking in an obnoxious way, like he’d play the hot jerk in a TV movie about why drunk driving is bad or how it doesn’t pay to cheat on the SATs. He’s got these big wraparound sunglasses on and a shiny black short-sleeve button-up shirt filled out with the kind of insanely sculpted arm muscles a person only gets when they spend most of their time lifting weights in the mirror and grunting at themselves.

“Hi,” I say. “What can I get for you?” I’ve been working here for a year but I still find it funny when I hear myself ask that, it’s like I’m a kid playing a game about working at a coffee bar, instead of a sixteen-year-old person who actually works at one.

The guy stares at the chalkboard behind me. “Can I haaaaaaaaave”—“a sugar-free skim iced chai.”

“A sugar-free skim iced chai,” I say. And I try not to look over at Brad, who I can feel watching us through the glass pastry case he’s washing.

“Hey, Ellie!” Brad calls out. He’s using his best “casual” voice, which is about an octave higher than his regular one. “Isn’t this such a coincidence? How we were just talking about sugar-free skim iced chais and how good they are? And now this customer is ordering a chai? What was that funny thing you were saying about them? About sugar-free skim iced chais?”

I feel my face turning red. The thing that’s fun about Brad is that he’ll say pretty much anything to anyone; this is also the thing that makes me want to throw a muffin at his head sometimes, one of those scary-huge ones that we sell here for five twenty-five.

I turn back to the guy and make an exaggerated shrug, like, “Who is this nut? And why is he cleaning the pastry case?” But the guy isn’t paying attention to any of this, anyway—he’s too busy checking out his reflection in the back of the espresso machine.

I make his drink and hand it to him. He watches the muscles in his forearm as he pays, and then turns around to leave, he makes it almost to the door, but then turns back at the last second and marches toward the counter. He’s holding his clear plastic cup up to his face. “This doesn’t taste like skim.” He jiggles the cup around. He stares at me, then down at the cup, then back at me. “You gave me a different kind of milk, didn’t you?”

He’s taken his sunglasses off. The skin around his eyes is too tan. And weirdly wrinkly. He makes this intense eye contact for a second, like I’ve been lying to him, but now that his glasses are off, I’ll finally have to ‘fess up.

“Nope,” I say. “That was definitely skim.”

“You’re positive about that?” He keeps the eye contact a second too long and then holds the cup up above his head, looks at the bottom of it, as if that’s where all the fat has deposited itself.

“I’m positive,” I say. “I can make you another one if you want.”

The guy just stands there. “No,” he says. And then he raises his eyebrows. “But I think we both know what you’re trying to do here.” He stands there one second longer, staring, and then finally turns and walks out the door.

I wait two beats after the doors close, then I turn toward Brad. The moment our eyes meet we burst out laughing. “Oh. My,” Brad says. He stands up, holding the spray bottle and rag to his hip. “I thought he looked kinda cute when he first came in, but I should have known his big, shiny glasses were hiding a face full of insaneness.” Brad shakes his head slowly. “Arms like that do not come without a price.”

“Um, speaking of insaneness?”

“Yeah, but I was doing it as a favor! If he had been anything resembling a normal person, my craziness would have been a great conversation starter!”

Brad puts the bottle and rag under the counter and then looks at his bright watch. “Okay, sweetness, you’re off soon, so before you go, I’m just going to run to the back and restock. If anyone comes in who I might think was your soul mate, make sure to tell him I said that he should give you his number!”

“Ha-ha,” I say.

“I’m serious,” Brad says. “Your very own Thomas could be just around the corner.” I roll my eyes. Thomas is Brad’s boyfriend who he met while working here. Thomas was a customer and Brad, who never gets nervous around anyone, was so nervous he dropped a piece of carrot cake on his own shoe. It was quite sweet actually. And they have been happily in love ever since.

Brad reaches out and grabs the end of one of my brown curls. He stretches it out straight and then lets it go. “Boing! ” he says, then flashes me a smile as he disappears into the back room.

I just smirk and shake my head. I pretend that it’s silly whenever Brad talks about finding me a boyfriend, that I don’t even want one. But the truth is, yes, I do. It’s just that not having something because you don’t want it is far less pathetic than wanting something you can’t have. I’m sixteen and in two months I’ll be a junior, but all of my guy experiences up until this point, a grand total of three brief make-outs with three different people, have been with friends of whoever my best friend, Amanda, was dating at the time, and just kind of happened randomly. Just once I’d like to kiss a guy because we actually like each other, not because we’ve been left alone by our respective friends, who are messing around in the next room, and have run out of stuff to say and need something else to do with our mouths.

I look out over the counter. It’s quiet in here, pretty average for an early Friday evening, before the nighttime rush. A dozen or so people are working on laptops or reading or talking quietly. A lanky guy with bright orange hair and an earring in each ear dumps his paper cup into the garbage and turns to wave as he walks out. Earl Grey, double tea bags, with extra milk. That’s what he drinks when he comes in here, which is only about once a month. Why do I know this? It’s the funny thing about working in a coffee bar, I guess. You get to know a tiny little bit about an awful lot of people. I don’t know most of my customers’ names or where they live or how old they are, but I know all the weird stuff they like to do to their caffeinated (or decaf) drinks.

Two girls approach the counter.

One is younger than I am, maybe fifteen or so. The other is older, probably around nineteen. The younger one has this big, bright, ecstatic grin on her face that is taking over all of her features. When you see a smile this genuine, it makes you realize just how many of the smiles you see during an average day aren’t. Looking at her, I find it almost impossib

le not to smile back.

The older girl has the same expression on her face, like there is light pouring out of her. And she has the same eyes. And similar bone structure and…There’s a weird tugging inside my chest as I realize something—they’re sisters, these girls. Instantly I know everything about them. And I feel a little sick.

They haven’t seen each other in a while. The older one was at college, or away on a long trip, and she’s just returned home. When she was gone, it felt like she’d been gone forever, but now that she’s back, it’s like she never left. Growing up, they fought a lot, Younger was jealous of Older, resented her and all the stuff she got to do that Younger didn’t. Older had always thought Younger was a pain, who would never leave her alone. But years have passed since then, and all that petty stuff that once seemed so important stopped mattering, the way it always does. Or the way it’s supposed to, anyway. They realized they can be friends now, real friends. And it means so much to both of them because they know how much they went through to get there.

I take a deep breath and try to keep my face completely still, expressionless. I know it’s not fair, but I suddenly hate them.

“Hi!” says Younger, perky behind long bangs. “We would like, um, some zucchini bread and…LaurLaur?” She looks up. “What else should we get?”

“Um, are the brownies good?” Older asks. And then smiles and lightly smacks herself in the forehead, “Why am I even asking, right? They’re brownies. So yeah, a zucchini bread, and a brownie of course, and a croissant…”

Younger starts giggling, “And another croissant! An almond one!”

“And an iced latte,” says Older. “And a cupcake and a smoothie and…”

The girls keep ordering, their smiles growing bigger and bigger, exchanging looks like coming here and ordering all this food is the culmination of a private joke. Probably something they’d been discussing for months while Older was gone, like, “When we’re together again, we’ll go to Mon Coeur…and order one of everything!”

I make their drinks and try to avoid eye contact. They’re chatty in that way people are when they’re just really happy, a little high on how happy they are.

“I just love this place,” says Younger.

“I know, I really missed it,” says Older. “I think, it’s what I missed most while gone. Yup!” She opens her eyes really wide and Younger mock punches her in the arm. Older grabs Younger around the shoulder and kisses her on the cheek and Younger pretends to wipe it off. They both laugh.

All their food is lined up on the counter now. I stand there staring at them.

“Oooh, sorry!” Older says. She takes out a lime green leather wallet, pays for everything with crisp new bills. “Thank you so much!” she says.

“Yes! Thank you!” says Younger. “So much!” It’s as though they’re giving me credit for how happy they are, as though just by being there to witness it, I had something to do with it.

It takes them three trips to carry all their food over to the table. Normally, I would have offered to help. But I just stand there watching. Older puts money in the tip jar—two dollars. No one ever puts in more than one. I can barely muster a “Thank you.”

Less than a minute later Brad is back, standing next to me. He watches me watching them, and puts one arm around my shoulder. “It’s time for you to go,” he says, and hands me a white paper bag. Inside are a dozen broken cookies iced in pink and green and white. “We can’t sell these,” Brad says. “I was going to give them to Thomas, but you should probably take them instead. Just make sure you remember to throw up after so you don’t destroy your adorable figure!”

I stick my nose in the bag and take a sweet breath of almondy air. The tightness in my chest starts to loosen. I am, I decide, very lucky to have Brad in my life who, for all his ridiculousness, knows exactly when I might need a big bag of cookie pieces. And also knows exactly when I won’t want to talk about why.

Two

I’m outside. The air is cooler now and the sun is going down. My eyes adjust to the dimming light as I walk.

I pass a day spa, a design store, a gourmet shop. I keep walking. Mon Coeur, where I work, and Attic, where my best friend Amanda works, are in the middle of town in Edgebridge, Illinois, which is a suburb of Chicago. It’s a fancy suburb for rich people, the Disneyland version of where people are supposed to live. There are beautiful new streetlights lighting up every corner and pink and orange flowers blooming in the tall wooden boxes that dot the sidewalk. In the fall this part of town is decorated with pumpkins and ears of dried corn, and in winter it’s all glittering Christmas lights and jingle bells. The town is about a two-minute drive from Amanda’s house, which is why we both got jobs here in the first place. There’s nowhere to work in my neighborhood, except liquor stores and used-car dealerships. Besides, I practically live at her house anyway.

Amanda’s waiting for me at the door to Attic. She kisses me on the cheek. Then she stands back and motions to her outfit. “I’m trying something out here, what do you think?”

She’s wearing a tiny navy-blue pair of kid’s running shorts, and a tiny boy’s ribbed white tank top. She has a pair of navy blue soccer socks pulled up to her knees.

“Well, if you’re trying out being a prepubescent boy, you forgot about a couple of rather important, ahem”—I stare directly at her boobs—“things.” We both laugh.

“I saw something like this in a magazine,” Amanda says. “You don’t think I can pull it off?”

“Oh, I think it would be very, very easy to pull off.”

“Ha-ha.” She adjusts her sock. “My parents are out tonight and so I’m thinking we should have a bunch of people over, including a lot of extremely hot guys we barely know. I’m sure they’ll like my outfit even if you don’t.” She sticks out her tongue and smiles. I can’t help but smile back. Amanda has a good life: Her parents love each other, she has two nice, funny brothers who she gets along with, and a giant house full of Jacuzzi tubs and flat-screen TVs, where everything looks beautiful and comfortable because someone has put effort into making it so, because they have the luxury of thinking about those things.

“What about Eric?” I ask. Eric is Amanda’s not-quite-boyfriend whose not-quite-ness is due to the fact that he continues to date other girls.

“I’m done with Eric,” Amanda says.

“Good,” I say.

And we both know this isn’t true, but we leave it at that.

“I already picked out some stuff for you,” Amanda says. She grabs my hand and leads me toward the back room, where we always try on clothes. “Good thing Morgette is rich, right?” Amanda grins, as though somehow she doesn’t realize her own family is pretty rich, too. Morgette, the owner of Attic, leaves early every Friday in the summer to go to her country house for the weekend, and she gives Amanda keys to the store so she can lock up. Basically this means that Amanda and I can pretty much borrow whatever we want from the store so long as we bring it back by Monday morning. The clothes are already used so it’s not even like it’s wrong or anything. All we’re doing is using them, y’know, a little bit more.

As I get dressed I tell Amanda about all the interesting customers who came in today—the skim milk guy, the lady with the obviously fake British accent, the guy with the parrot on his shoulder, the girl who ordered while her boyfriend was nibbling on her ear. Amanda laughs at all the funny parts and rolls her eyes at all the eye-rolly parts. I don’t mention anything about the sisters, though. Amanda’s my best friend, but even with her there are limits to what I feel like I can say.

A few minutes later I’m standing barefoot in front of the mirror wearing a tiny boy’s white button-up shirt (the sleeves reach just past my elbows), a wide gold belt, and a floaty white skirt with gold threads running through it that reaches just below my butt.

I stare at myself in the mirror.

Amanda is behind me. “Stop frowning,” she says to my reflection. “As usual you look hot spelled with about five ext

ra t’s.”

“Ha-ha,” I say, and roll my eyes.

Truth is, no matter how much time I spend staring into the mirror, I don’t really have any idea what I actually look like. Does anyone?

I’m not tall and I’m not short, and I’m on the thin side but I’m definitely not skinny. I have curly hair that reaches to the middle of my back, it’s light brown but gets blonder in the summer. The guy who cuts it is always telling me that it’s “gorgeous and luxurious” but then he tries to sell me a whole bunch of products to “tame and define,” none of which I ever end up getting, which is okay since I usually just wear a ponytail most days, anyway. My face gets blotchy when I get nervous or embarrassed, but other than that, my skin is okay, I think. My eyes are big and green. My nose is kind of round. I have one dimple. Whenever I see pictures of myself, my smile looks crooked.

Amanda tosses me a pair of gold lace-up sandals that look like they could be part of a costume in a play about ancient Greece.

“Try these,” she says.

I sit down and slip off my shoes. There’s a cardboard box next to me on the floor with Sunny Grove Citrus printed on it in orange and green.

“What’s in here?” I poke the box.

“Crap Day,” Amanda says. “The third Friday of every month Morgette buys anything anyone wants to get rid of for twenty-five cents a pound.”

“Anything?” I ask. “Like old bananas and expired vitamins?”

“I guess enough people accidentally sell her first editions of old books or pieces of antique silverware that it makes it worth it.” Amanda shrugs.

I sit down on the floor and start digging through it—a bag of plastic spiders, three unopened jars of cloves, a glob of dried-up neon Play-Doh, and at the bottom of the box a copy of a book with the cover ripped off—Encyclopedia of Abnormal Psychology.

“Hey, Amanda,” I say. I pick up the book and stand, “Do you think we’ll find Eric’s picture in here under…” but then I stop.

A rectangular piece of cardboard with slightly rounded edges, a little smaller than an index card, has fallen out of the book and f luttered to the floor. I reach out and grab it. As soon as my skin touches it, my heart starts pounding, and I feel dizzy, like I’ve been spinning and just stopped. The room tilts. Everything around me looks wrong all of a sudden, and I think maybe I’m going to pass out. I sink to the floor; I’m vaguely aware of Amanda’s voice calling my name, but I can’t answer. She sounds far away and unfamiliar. Everything is unfamiliar, except for one thing. The piece of paper in my hand, covered in blue vines. I stare at them so hard they begin to swirl, like delicate navy thread snakes on a field of white. And in the center of these vines is a drawing of a girl: big round eyes, round face, round nose, crazy hair curling out in all directions, one dimple, a crooked smile. I know this drawing.