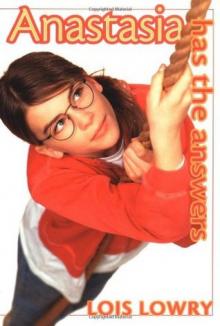

Anastasia Has the Answers

Lois Lowry

Anastasia Has The Answers

Lois Lowry

* * *

Houghton Mifflin Company

Boston

* * *

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lowry, Lois.

Anastasia has the answers.

Summary: Anastasia continues the perilous process of

growing up as her thirteenth year involves her in

conquering the art of rope climbing, playing Cupid for

a recently widowered uncle, and surviving a crush on

her gym teacher.

[1. Humorous stories] I. Title.

PZ7.L9673Amg 1986 [Fic] 86-330

ISBN 0-395-41795-3

Copyright © 1986 by Lois Lowry

All rights reserved. For information about permission

to reproduce selections from this book, write to

Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Company, 215 Park Avenue

South, New York, New York 10003.

Printed in the United States of America

VB 20 19 18 17

1

"I would sort of like to go," Anastasia said, "because I've never been on an airplane in my life and I would sort of like to take a plane trip."

"So shall I make three reservations? Have you decided?" Her mother was sitting beside the telephone and she had the yellow pages open to airlines. With her ball-point pen she drew a circle around a number and reached over to dial.

"Weeeellll," Anastasia said indecisively, "I think I might be scared of flying. Maybe I ought to start my flying career with a real short flight, just to Nantucket or something, instead of all the way to California."

Mrs. Krupnik sighed. "All right then. If that's how you feel, maybe you're correct. I'll make two reservations, for Dad and me."

Anastasia began to chew on a strand of hair. "On the other hand—" she said, with hair in her mouth.

"On the other hand what?"

"I've never been to California in my life. This may be my only chance. And since I've decided to become a journalist, I should be open to new experiences."

"I guarantee you will have other opportunities to go to California. However, if you want to go tomorrow, you have to say so right now, Anastasia."

"I have an English test tomorrow, on Johnny Tremain. So I should stay here."

"Look at me," her mother announced. "Watch my finger closely. I'm dialing the phone. Make up your mind." She pressed several of the buttons on the telephone.

"But I hated Johnny Tremain," Anastasia went on. "I'll probably flunk the test. So maybe I should go."

"It's ringing," her mother announced. "Decide."

"But of course it's not going to be a fun trip or anything. No time to go to Disneyland. You did say that, didn't you, Mom, no Disneyland, no movie stars' houses or anything?"

Her mother nodded. She was listening intently to the voice on the telephone. Finally she looked up in disgust. "Rats," she said. "I'm on hold. A recording told me that all their personnel are busy at the moment. Do you believe that? I don't. I think they're all drinking coffee."

She held the receiver out, and Anastasia listened for a moment to the music playing. "Yeah," she said. "They're probably all hanging out together, drinking coffee. But it does give me another minute to decide. If I go, all my friends will be jealous, which would be nice. But probably I should stay, to help take care of Sam."

"Sam will be fine. It's only two days, and Mrs. Stein loves taking care of him."

"Realistically, Mom, what do you think the chances are of a movie scout noticing me during two days in Los Angeles?"

"Realistically? Zero."

Anastasia scowled. "You could have said something more supportive, Mom," she said.

"I'm being honest, and honesty is supportive. Here are the facts, Anastasia: it will be an exhausting trip, out to Los Angeles and back for only two days. It will not be fun, no Disneyland or tours of movie studios. On the other hand, Dad and I would be happy to have you come with us, and your Uncle George would appreciate it, I know, and—Yes? Hello?" She turned back to the telephone. Someone had finally answered.

Anastasia shook her head hard. "No," she said. "I don't want to go."

"One moment, please," her mother said into the phone. She covered the receiver with one hand and turned to Anastasia. "You're sure? You don't want to come?"

"Positive. I'll stay here."

Mrs. Krupnik spoke again into the telephone. "I'd like two reservations, please, from Boston to Los Angeles tomorrow morning, returning on Thursday. Myron and Katherine Krupnik."

Anastasia got up from her chair and wandered over to the refrigerator. She took out a piece of leftover chicken, two pickles, some grapes, and a chunk of cheese; carefully she piled it all on a plate and took it to the kitchen table. She began to eat, even though it would be dinnertime in an hour. She was starving. Decision-making was so hunger-producing when you were thirteen.

***

Later in the evening, after Sam was in bed, Anastasia wandered into her parents' bedroom to watch them pack for the trip.

"Would you guys like to know the real reason I decided not to go with you?" she asked.

Her father was polishing a pair of shoes that he planned to pack. Her mother was putting some jewelry into a small traveling case. They both looked over to where Anastasia was standing in the doorway, eating an apple.

"Sure," her father said.

"I was scared," Anastasia confessed.

"Of flying?" her mother asked. "You mentioned that. I was surprised. You're not usually scared of new experiences."

"No," Anastasia said, "not of flying. I'd really like to go someplace in an airplane. The new experience I'm scared of is—yuck, I even hate the word—funerals."

"But Anastasia," her mother said, "you went to your grandmother's funeral when you were only ten years old. I remember that you behaved beautifully and that afterward you said you had liked being there, that it was a nice chance to hear people talk about your grandmother and their memories of her."

Anastasia bit into her apple again. "True," she said, chewing. "But you can see what the difference is. The age thing, for one."

"Well, you were ten then, and you're thirteen now. You're more mature—that should make it even easier," her mother said.

"I mean the age of the, ah, the deceased person," Anastasia pointed out.

Dr. Krupnik nodded. "I can understand that. Your grandmother was in her nineties, and your Aunt Rose—well, let me see. Katherine, how old was Rose?"

Mrs. Krupnik wrinkled her forehead, thinking. "Fifty-five, maybe?" she said, finally.

"See?" said Anastasia. "That's old, but still, it's not like ninety-two. And also, there's the other thing."

Her parents looked at her.

"Other thing?" her mother asked.

Anastasia cringed. "I don't quite know how to say it. Cause of Death."

Her parents both nodded. They looked very sad.

"Grandmother just died in her sleep, remember? And that seemed okay, because she was so old and tired, anyway. But Aunt Rose—well, I'm sorry, Dad, because I know she was your brother's wife and all, and I guess she was an okay lady, even though I don't really remember her because I hadn't seen her since I was little, but I have to tell you that I am really grossed out by her Cause of Death."

"Food poisoning? It's tragic," her father said, "but I wouldn't call it gross."

"That other word. I heard you say it to Uncle George on the phone."

"Salmonella."

"YUCK!"

"Why yuck? It's the medical term for a particular kind of food poisoning."

Anastasia made a face. "It sounds like someone's name. A mobster. A hit man.

My Aunt Rose was killed by Sal Monella. It sounds like something a journalist should write about. By the way, do you know that when you write a newspaper story you should answer the questions 'who, what, when, where, and why' right in the very first paragraph?"

Dr. Krupnik sighed and put his newly polished shoes into the suitcase. "Well, here's the who, what, when, where, and why," he said. "Your Aunt Rose was unfortunately killed last night by one of the finest restaurants in Los Angeles, where she made the mistake of ordering some food that had not been properly stored and refrigerated. And as a result, incidentally, your Uncle George will no doubt collect a fortune in a legal settlement."

"No kidding? Uncle George will be rich?"

"I'm quite sure he would much prefer to have Rose back," Mrs. Krupnik said. "They never had a lot of money, but they were very happily married." She put a blouse into the suitcase, and sighed. "Poor George. This is going to be a sad, sad funeral, Myron," she said. "Anastasia's right. I don't blame her for not wanting to go."

"Since I'm not going, I should be reading Johnny Tremain again," Anastasia confessed gloomily. "I know I'll flunk the test."

"No, you won't," her father reassured her. "You always do well in English."

Anastasia sat down in the middle of her parents' king-sized bed and curled her legs up under her. She tossed her apple core into the wastebasket. "I wish they'd assign Gone with the Wind in seventh-grade English," she said.

Her mother looked over from where she was folding a nightgown. "They couldn't," she said. "It's too risqué."

"Mom," Anastasia said, "there isn't a single sex scene in Gone with the Wind. And only one 'damn.' Remember when Rhett Butler says to Scarlett—"

"'Frankly, my dear, I don't give a damn,'" Mrs. Krupnik said in a deep voice along with Anastasia, and they both laughed.

Dr. Krupnik made a face. "It's terrible literature," he said.

"But it's so romantic, Dad. I love romance. I wish someone would say to me, in a deep voice: 'Frankly, my dear, I don't give a damn.' Someone rich and handsome, with a mustache, like Clark Gable."

Anastasia pulled her long hair up into a pile on top of her head. She rose to her knees so that she could see herself in the mirror on the opposite wall. With one hand, she held her hair in place, and with the other she pulled the neck of her sweat shirt down over one shoulder. "Do you think I have a swanlike neck, Mom?" she asked.

Her mother glanced over at Anastasia's neck. "Long and skinny, yes," she said. She went to the closet. "Myron," she asked, "what ties do you want to take? You'll need something dark and somber, for the services."

Anastasia pulled her sweat shirt tight around her and looked sideways toward the mirror, to see her body in profile. "Would you call me voluptuous?" she asked.

"No," said her father. "Thank goodness. I don't want a voluptuous thirteen-year-old daughter. You can be voluptuous when you're twenty-seven, not before."

Anastasia flopped back down on the bed and sighed. "Well," she said, "I don't know any rich, handsome men with mustaches anyway. I just know obnoxious seventh-grade boys. None of them even shave yet."

Her mother snapped the suitcase closed. "There," she said. "All set. Anastasia, when you get home from school tomorrow, Mrs. Stein will be here, with Sam. Give her a hand with things, would you? And we'll be back late Thursday afternoon."

"It's ten o'clock, Anastasia," said her father. "You ought to be getting to bed."

Anastasia disentangled her legs and stood up. She kissed her father and her mother and went to the hall.

"Don't be dismayed if you notice lights in my room all night long," she called back to them. "I will probably be reading Johnny Tremain three or four times, because I know how important it is to you guys that I get an A in English."

She could hear her father's voice respond as she headed up the stairs to her third-floor bedroom.

"Frankly, my dear," he was calling in a deep voice, "I don't give a—"

Giggling, Anastasia closed her door. She sprawled on her bed and took out the notebook in which she was practicing for a journalism career.

2

The test on Johnny Tremain was grim. Anastasia hadn't bothered looking at the book again the night before. Now, in school, she answered the questions as well as she could—but she knew it wasn't very well.

When she had finished, she leaned back in her seat and stared out the window of the classroom. Maybe, she thought, instead of a journalist, she should be an English teacher when she grew up. Probably there was a rule that seventh graders had to read a historical novel—that was why they assigned Johnny Tremain every year. But she, when she became an English teacher, would definitely assign Gone with the Wind in seventh grade.

She began to compose a test on Gone with the Wind. The short-answer questions were easy: the names of Scarlett's sisters, stuff like that.

Essay questions were tougher. But Anastasia had a good one:

"Scarlett O'Hara seemed to think that Ashley Wilkes was a wimp. Do you agree, or disagree? Give your reasons."

Anastasia sort of agreed. Ashley and Melanie were both kind of wimpy. But she wasn't exactly sure why. She tried to think of some reasons. If they had lived in current times, Melanie probably would have worn lace-up shoes. Ashley would have gone to the symphony instead of rock concerts—just like Anastasia's father, who was occasionally pretty wimpy himself, in a lovable sort of way.

"Anastasia?"

She jumped. It was Mr. Rafferty, standing by her desk and reaching for her test paper. Blushing, she handed it to him.

"Sorry," she said. "I finished a while ago, and I was thinking about other stuff."

"The poem you're memorizing for next week, I hope," Mr. Rafferty said.

"No sweat, I know it by heart already. I gotta go, Mr. Rafferty. I can't be late for my next class."

The other kids in the class were already out of their seats and heading for the hall. Hastily Anastasia grabbed her books and followed them. She caught up with her friends Sonya and Meredith on the way to gym.

"Where's Daphne?" Anastasia asked. Daphne Bellingham shared her gym locker, and they always went to the gym class together. But lately it had been hard to find Daphne a lot of the time.

Meredith sighed. "She's in the guidance office again. Poor Daph. I wish her problems would go away."

"Yeah, me too," Anastasia agreed. "But it would take a U-Haul van to haul them off, she has so many."

"Well," Sonya said optimistically, "at least she's getting Guidance. That's what the Guidance Counselor is for."

"Mrs. Farnsworth?" Anastasia said cynically. "You really think that Mrs. Farnsworth can do anything for Daphne?"

Meredith and Sonya chuckled. Mrs. Farnsworth was a wimp for sure. Compared to Mrs. Farnsworth, Melanie in Gone with the Wind was a punkrocker.

And Daphne did have big problems. Her parents had separated and were being divorced. Her father, the Congregational minister, was staying in the church rectory where the family had lived, and Daphne and her mother had moved to a small apartment. Daphne's mother had started a job as a secretary in a lawyer's office.

"Remember Alice in Wonderland, how she drank from that weird magic bottle and ate that freaky cookie and went from large to small and back again? That's how I feel," Daphne had explained to Anastasia. "Family, no family. House, no house. Money, no money. Surprises every day. I never know when I wake up in the morning what that day's surprise will be."

Anastasia hadn't known what to say. "I'm really sorry," was the best she could do.

Now, as she hurried to gym with her friends, she heard the latest news about Daphne. "Her father has a girlfriend, one of the Sunday school teachers at his church," Meredith explained in a whisper. "And Daphne can't decide whether to be nice to her or not. Daphne likes the lady okay, but of course her mother is sort of inclined to commit a really violent murder, maybe bashing the lady over the head with a Bible stories book."

"And Daphne wants to be supportive of her mother," Sonya went on,

"so she doesn't really know what to do."

"Well," Anastasia said dubiously, "I don't know what to suggest. I don't even think I could write a newspaper article about Daphne's family. The whos and whats and whens and wheres and whys are too complicated."

***

In the gym, Anastasia stood in line with the other girls when Ms. Willoughby blew her whistle. But her shoulders were slumped. She wasn't even thinking about Daphne—who was still in the guidance office and hadn't shown up for gym—anymore. She was thinking about herself, and about the disgusting ropes hanging from the ceiling of the gym.

Everybody else in the class—even Sonya, who was overweight—could climb those ropes. But Anastasia couldn't. She could do everything else okay—all the gymnastics stuff, even the parallel bars and the horse—but she couldn't climb the ropes at all.

And Ms. Willoughby had just announced that they were going to do rope-climbing first, before playing basketball.

I love almost everything about Ms. Willoughby, Anastasia thought. I love her looks (Ms. Willoughby was a tall, lanky black woman); and I love her clothes (in gym class, Ms. Willoughby wore a Vassar sweat shirt and blue denim shorts; out of gym, she wore layers of high-fashion skirts and shirts and sweaters, sometimes several on top of each other—Anastasia thought it the most glamorous way of dressing she had ever seen); and I love her personality (Ms. Willoughby was witty and cheerful and funny); and I love her name (Ms. Wilhelmina Willoughby).

But I hate, hate, HATE her ropes.

Anastasia had even tried to think of a way to sneak into the junior high school gym after dark, when no one was there, and to climb up and take down those six hateful ropes.

But there was no way to do it. She couldn't climb them to begin with—that's why she hated them. So how could she climb up to take them down? Even if she could manage that, she would be left way up there perched in the rafters, about a million miles high.

"Six lines, ladies!" Ms. Willoughby blew her whistle and the seventh-grade girls formed six lines. Anastasia stood miserably at the end of one, waiting.