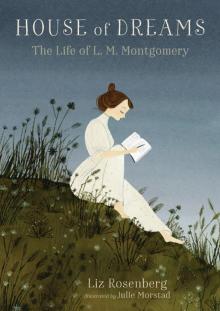

House of Dreams

Liz Rosenberg

Chapter One: A Bend in the Road

Chapter Two: An Early Sorrow

Chapter Three: “Very Near to a Kingdom of Ideal Beauty”

Chapter Four: The Jolly Years

Chapter Five: Room for Dreaming

Chapter Six: Count Nine Stars

Chapter Seven: “Darling Father” and Prince Albert

Chapter Eight: The Pill inside the Jam

Chapter Nine: The Happiest Year

Chapter Ten: Schoolmarm in Bideford

Chapter Eleven: HALIFAX!

Chapter Twelve: Belmont and the Simpsony Simpsons

Chapter Thirteen: The Year of Mad Passion

Chapter Fourteen: Back in the House of Dreams

Chapter Fifteen: The Creation of Anne

Chapter Sixteen: “Yes, I Understand the Young Lady Is a Writer”

Chapter Seventeen: “Those Whom the Gods Wish to Destroy”

Chapter Eighteen: A Changed World

Chapter Nineteen: A Woman “They Cannot Bluff, Bully, or Cajole”

Chapter Twenty: Dashing over the Traces

Chapter Twenty-One: Journey’s End

Epilogue

Time Line of L. M. Montgomery’s Life

Source Notes

Bibliography

Acknowledgments

On a late June afternoon in 1905, Maud Montgomery sat in her grandmother’s kitchen, writing. She sat not at the kitchen table, but perched on top of it, her feet set neatly on a nearby sofa, her notebook propped against her knees. From here she could jump down if someone stopped by for their mail, as was likely to happen — for the kitchen doubled as the post office of Cavendish, a tiny seaside village on Prince Edward Island.

Maud was thirty, but she looked younger, barely out of her teens. She had large, sparkling gray-blue eyes with long eyelashes, and a small mouth she sometimes covered with her hand, since she thought her teeth her worst feature. She was medium height, slight, trim, and erect. Maud believed her one beauty to be her lustrous hair, a feature she’d inherited from her late mother. When she let it down at night, her hair hung past her knees in masses of soft brown waves. But most of the time she wore it up, pinned under the most fanciful and elaborate hats she could find.

At this moment Maud was working on a new story. Though she had just begun, she felt immediately transported to another world — a Cavendish-like place she would call Avonlea. Something about this story and its eager, orphaned heroine (“please call me Anne spelled with an e”) gripped Maud from the start. The words flowed smoothly onto her notebook. Her handwriting was never stronger or more sure. Maud began her tale not with her famous red-haired heroine but with the town of Avonlea itself and the sharp-eyed Mrs. Lynde who guards it. Maud wrote in one rushing paragraph-long opening sentence:

Mrs. Rachel Lynde lived just where the Avonlea main road dipped down into a little hollow, fringed with alders and ladies’ eardrops and traversed by a brook that had its source away back in the woods of the old Cuthbert place; it was reputed to be an intricate, headlong brook in its earlier course through those woods, with dark secrets of pool and cascade; but by the time it reached Lynde’s Hollow it was a quiet, well-conducted little stream, for not even a brook could run past Mrs. Rachel Lynde’s door without due regard for decency and decorum; it probably was conscious that Mrs. Rachel was sitting at her window, keeping a sharp eye on everything that passed, from brooks and children up, and that if she noticed anything odd or out of place she would never rest until she had ferreted out the whys and wherefores thereof.

The day was dazzling after rain, and Maud sat in the late sunlight flooding in. Her moods were like the weather — brilliant one minute, overcast the next. June was Maud’s favorite month. You could practically count her happiness by Junes. She wrote about it more than all the other months combined, naming each of its beauties. When spring finally swept the north shore of Prince Edward Island, Maud abandoned her small, dark “winter bedroom” off the downstairs parlor and moved upstairs, where she could write and dream uninterruptedly. No one else ventured up there; hidden, Maud was queen and sole resident of her springtime domain. But now she was working out in the open, intent on her new story, her pen racing to catch up to her thoughts.

She had just reached the point where nosy Mrs. Lynde wonders at her shy neighbor, Matthew Cuthbert, heading out with the buggy and sorrel mare, wearing his best suit: “Now, where was Matthew Cuthbert going and why was he going there?”

Just at this moment, Maud was interrupted. The new minister in town, Ewan Macdonald, stopped by for his mail. Maud set her writing aside. Ewan was a shy, gentle bachelor who had lately moved to Cavendish, taking a room within walking distance of the Presbyterian Church, next door to the Macneill homestead, her grandparents’ house. He was a frequent visitor to the post office. To Maud, the young minister seemed a bit lonely. He was well educated, with hopeful prospects. Ewan Macdonald attracted local attention with his dark wavy hair, dimples, and lilting Gaelic accent. The accent was especially appealing to Maud, since she’d grown up hearing romantic tales of Scotland, the Old Country.

A handsome unmarried minister was a natural target for local gossip. The Cavendish girls were rumored to be “crazy about him,” and more than a few threw themselves in Ewan’s path. Maud was not one of them. She liked the shy Scotsman and enjoyed his company, but she was not looking for a suitor. She’d already had a few too many ardent proposals, but she was always hungry for a new friend. Maud welcomed the new minister’s company, and kept the conversation light. If she felt flattered — or interested — she didn’t let on, and that was a relief for Ewan Macdonald, who had just escaped a near marriage to an overeager woman in another town.

The Macneills had been staunch Presbyterians as far back as anyone could remember. Maud was the church organist; she was merry, she was bright, and she and Ewan had plenty to talk about. Ewan lingered as long as daylight held out; only when the kitchen grew dappled with shadows did he reluctantly leave with his letters. Maud picked up her notebook and carried it upstairs.

She had come to a bend in the road — though at that moment she could not see around it. It seemed merely the end of a vibrant June day. She had a new friend in town, and she had begun a new story. Maud had no way of knowing that absolutely everything in her life was about to change.

Lucy Maud Montgomery — “call me Maud without an e,” she would insist, discarding the use of Lucy altogether — grew up proud of her long, deep roots in the history of Prince Edward Island.

On cold Canadian nights, the Macneill family gathered around the kitchen stove and talked. And talked. Little Maud sat at the knee of her great-aunt Mary Lawson, wide-eyed. Aunt Mary Lawson was a wonderful storyteller. Tales of ancient grudges, courtships, and adventures were discussed as eagerly as that morning’s gossip. Those old stories provided the first clues to Maud about who she came from, and who she might become. She never forgot them. Maud came to know her Prince Edward Island ancestors as well as she knew her own neighbors.

In the 1700s Maud’s seasick great-great-grandmother Mary Montgomery came aground at Prince Edward Island for a few minutes’ relief, and then, to her husband’s horror, refused to board ship again. He could beg and plead and fume, but she would not budge. Right there on Prince Edward Island they would and did stay. Maud’s family history began on the heels of one stubborn, seasick, strong-willed woman.

The Montgomerys traced their lineage back to the Scottish Earl of Eglinton — a dubious connection, but one Maud’s father clung to. (He would one day name his own house Eglintoun Villa.) Maud’s paternal grandfather, Donald Montgomery, was a staunch Conservative. Among his friends he counted the first prime minister of Canada and leading members of the Conservative Party. Donald Montgomery

served in the Prince Edward Island legislature for more than forty years and then in the Senate another twenty till his death at age eighty-six. He was known simply as “the Senator.”

The Senator kept on his mantel two large china dogs with green spots. According to Maud’s father, each midnight they would leap down from the shelf to the hearthrug. The story — and the spotted china dogs — enchanted little Maud. As patiently as she watched, she never caught them coming alive. But she never forgot them, either. Years later, on her honeymoon, when she spied two large spotted china dogs for sale, she snapped them up and shipped them home to guard her bookcase. They were vivid, proud reminders of her father’s side of the family.

On Maud’s maternal side, the Macneills were equally well-known and respected — all of them dedicated Liberals, or Grits. This put them directly in political opposition to the Montgomerys. In this and in much else, Maud would find herself torn between two powerful and contradictory forces.

Maud’s maternal great-great-grandmother Elizabeth was as stubborn as the seasick one — but less successful at swaying her husband. She hated Prince Edward Island. “Bitterly homesick she was — rebelliously so. For weeks after her arrival she would not take off her bonnet, but walked the floor in it, imperiously demanding to be taken home. We children who heard the tale never wearied of speculating as to whether she took off her bonnet at night and put it on again in the morning, or whether she slept in it.”

Maud’s home village of Cavendish, on the central north coast of Prince Edward Island, was founded in the late 1700s by three Scottish families: the Macneills, the Simpsons, and the Clarks. By Maud’s day, she noted, these three important families “had intermarried to such an extent that it was necessary to be born or bred in Cavendish in order to know whom it was safe to criticize.” There was a tart local saying about these families: “From the conceit of the Simpsons, the pride of the Macneills, and the vain-glory of the Clarks good Lord deliver us.”

Maud came from the “proud” Macneills. She claimed that her “knack of writing . . . and literary tastes” sprang from this maternal side of the family. Her maternal great-grandfather, William Simpson Macneill, was a powerful Speaker of the House — it was said that he knew by name every man, woman, and child on Prince Edward Island. Even his portrait looked so formidable that one of his successors, still intimidated by it one hundred years later, finally had it taken down and hidden away.

One of the Speaker’s eleven children became a noted politician, another a well-known lawyer, but Alexander Macneill, Maud’s grandfather, was simply a farmer and the local postmaster. It was said he had possessed many of the Speaker’s best qualities — eloquence, dignity, intelligence — but also his weaknesses to a serious degree. Grandfather Macneill was proud, sharp-tongued, tyrannical, and hypersensitive. He picked fights with family and neighbors that turned into long-term feuds.

Undoubtedly Grandfather Macneill was proud of his clever granddaughter Maud, but his method was to praise in private and bully or ridicule in public. Maud had to learn from her cousins that her fierce grandfather whispered complimentary things behind her back.

She shrank from Grandfather Macneill’s razor wit. Maud hated the way he mocked and belittled her — and he couldn’t help doing it. Her most famous literary creation, Anne Shirley, shares her aversion: “sarcasm, in man or woman, was the one weapon Anne dreaded. It always hurt her . . . raised blisters on her soul that smarted for months.” Likewise, Maud’s fictional Story Girl vows never to make fun of a child: “. . . it IS hateful to be laughed at — and grown-ups always do it. I never will when I’m grown up. I’ll remember better.”

Maud was proud of her family, but her legacy was far from easy. Both sides were fully convinced of the rightness of their ways. Maud knew that she had inherited qualities from the Montgomerys and the Macneills destined to be forever at odds: “the passionate Montgomery blood and the Puritan Macneill conscience.” She also understood that neither side was “strong enough wholly to control the other.” The two sides battled it out endlessly in Maud’s double nature.

Maud put a brave face to the world, protecting and hiding the inner Maud. “I lived my double life, as it seems to me I have always done — as many people do, no doubt — the outward life of study and work . . . and the inner one of dreams and aspirations.”

Maud’s life began in joy but turned to early sorrow. Both the joy and the sorrow left their mark. Lucy Maud Montgomery was born November 30, 1874, in the Prince Edward Island town of Clifton — later renamed New London — in a tiny two-floor cottage, eight and a half months after her parents’ wedding.

Her father, Hugh John Montgomery, was thirty-three years old, the handsome, merry, likable but unlucky son of Senator Donald Montgomery. When Hugh John first met Maud’s mother, Clara Woolner Macneill, he cut a dashing figure as a young sea captain. Ever the optimist, he swept all opposition aside to claim his young bride.

Clara Woolner Macneill was a young woman of twenty-one, the fourth of her parents’ six well-protected children. In the little village of Cavendish, Clara stood out. She turned heads with her beauty, and won more than one suitor’s heart. In later years, a gray-haired man approached Maud and shyly bragged that he had once had the honor of walking her mother home.

Clara and Hugh John were married in her parents’ parlor, but the elder Macneills never really approved the match. Hugh John seemed unlikely to become a good provider. Hugh John’s father, Senator Donald Montgomery, bought the young couple a small cottage on Prince Edward Island, halfway between the two sets of parents.

The young couple struggled to make a living by running a country store attached to their living quarters. Neither husband nor wife was good at business. The store floundered. And all too soon, Clara fell ill with tuberculosis — or consumption, as it was then called — a slow, dreadful, and often fatal lung illness.

Hugh John moved to Cavendish, where the Macneills could help care for their daughter and infant granddaughter, Maud. Despite all their vigilance and attention, Clara Macneill Montgomery died on September 14, 1876, leaving behind one baby daughter and a grieving husband and family. She was twenty-three years old. Maud was not yet two. Her first memory was of her young mother lying in a coffin, her golden-brown hair spilling around her shoulders.

Hugh John stood by the casket, cradling Maud in his arms and crying. The tiny girl was bewildered: a crowd had gathered, she was the center of attention, yet something was wrong. Neighbors whispered to one another and looked at them pityingly.

Women in Maud’s day owned only one silk dress in their lifetime, usually in some sensible, muted color; Clara’s silk was a vivid green. Maud’s mother looked glamorous even in death. With her mass of wavy golden-brown hair, she seemed as lovely and familiar as ever. But when Maud reached out to touch her mother’s face, she was shocked by her ice-cold skin, a sensation so strong that years later Maud could feel it searing her fingertips.

After the funeral, a veil of silence fell over Clara Macneill Montgomery’s brief life. Maud had to cobble together an image of her mother through snatches of overheard conversation and dropped hints. It was as if her mother had been erased.

From the few accounts Maud could glean, Clara had been a sensitive, poetical, high-minded, and dreamy young woman. It took courage for her to defy her parents and marry against their wishes. Maud and Clara stood out from their little clan. Both loved beauty to a degree that was considered almost madness. Maud forever mourned the loss of her mother. Though Clara died young and unknown, she left behind a few items that Maud treasured all her life — a few volumes of poetry, a daybook that Maud carefully preserved.

Clara’s grave lay just across the road from Maud’s house and the Presbyterian Church, beside the schoolhouse. Her mother’s absence was always in sight: aching, mysterious, and unforgettable. Maud crossed through her mother’s graveyard on her way to and from school each day.

Clara’s early death left Maud with unanswered questions. Though th

e Macneill family was famous for storytelling, no stories about her mother came Maud’s way. Nor did anyone sit down with Maud to discuss a possible afterlife. She was left to draw her own conclusions.

At age four, Maud was in church when the minister said something that made her sit up and take notice. One was never supposed to speak in church, of course, but this was urgent. Maud turned to her aunt Emily and piped, “Where is Heaven?”

Young Aunt Emily was too proper to answer aloud. Instead she pointed her finger up toward the ceiling. From this gesture, Maud concluded that her mother was somehow stuck in the attic of the Clifton church. Heaven was only a few miles from home! Maud could not understand why someone didn’t get a ladder and fetch her mother down.

Meanwhile, Maud’s home life with her father grew more insecure. Hugh John grieved for his young wife, and as he struggled to make a living, he left the care of his active young daughter to the Macneills, who were in their fifties, well past their years of child rearing. Only their teenage daughter, Maud’s prim aunt Emily, still lived at home. Maud thought of her young aunt as ancient. “Either you were a grown-up or you were not, that was all there was about it.” Aunt Emily was no sort of playmate, so Maud invented her own playfellows, even in the glass doors of a cupboard in her grandparents’ parlor.

In the left-hand door dwelled Maud’s imaginary friend, Katie Maurice. Katie was a little girl Maud’s own age, to whom she would chatter “for hours, giving and receiving confidences.” Maud could never poke her head into the parlor without at least waving her hand at Katie Maurice.

On the right side of the cupboard door lived the imaginary Lucy Gray, an elderly widow who always told “dismal stories of her troubles.” Maud much preferred the imaginary company of Katie Maurice, but in order to spare the feelings of the sad old widow, she was careful to spend equal time chatting to both.

Much later, Maud would bring just the favorite of her two invented friends to Anne of Green Gables, where Katie Maurice became Anne’s imaginary first best friend and comforter.