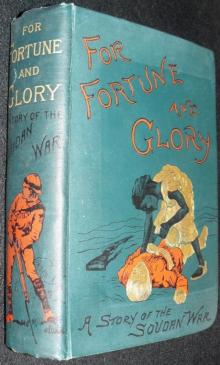

For Fortune and Glory: A Story of the Soudan War

Lewis Hough

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

For Fortune and GloryA Story of the Soudan War

By Lewis Hough________________________________________________________________________We were a little nervous to know how Lewis Hough got on writing a bookwith such a very different setting to his masterly "Doctor Jolliffe'sBoys." In fact the story opens in a boarding school (the British PublicSchool) called Harton. This is probably meant to be a word based on"Eton" and another school that has an annual cricket match with Eton,called "Harrow". In fact there is plenty of internal evidence that itreally is Eton, with the dropping of local slang terms only in use atthat school.

Before I knew the story I was also nervous about the title. What couldFortune possibly have to do with the Soudan War? What actually happenedwas that a certain Will had been stolen by a former employe, anEgyptian, of a Dublin solicitor, together with a previous version of theWill. This had resulted in a family losing all their money, since thefather had been a Partner in an Eastern Bank that foundered in theevents leading up to the Soudan War.

Eventually the two Wills are tracked down, and justice done as regardsthe estate.

But all this is a parallel story to the description of events in theSoudan War. This is well worth reading for its own sake, especially inthis day and age, when certain events seem about to repeat themselves.NH________________________________________________________________________

FOR FORTUNE AND GLORYA STORY OF THE SOUDAN WAR

BY LEWIS HOUGHA STORY OF THE SOUDAN WAR.

CHAPTER ONE.

A MYSTERIOUS RELATIVE.

It is nice to go home, even from Harton, though we may be leaving allour sports behind us. It used to be specially nice in winter; but youyoung fellows are made so comfortable at school nowadays that you missone great luxury of return to the domestic hearth. Why, they tell methat the school-rooms at Harton are _warmed_! And I know that theSenate House at Cambridge is when men are in for their winterexaminations, so it is probable that the younger race is equallypampered; and if the present Hartonians' teeth chatter at six o'clocklesson, consciousness of unprepared lessons is the cause, not cold.

But you have harder head-work and fewer holidays than we had, so you arewelcome to your warm school-rooms. I am not sure that you have the bestof it: at any rate, we will cry quits.

But the superior material comforts of home are but a small matter in thepleasure of going there after all. It is the affections centred in itwhich cause it to fill the first place in our hearts, "be it never sohumble."

Harry Forsyth was fond of Harton; fond of football, which was in fullswing; fond of his two chums, Strachan and Kavanagh. He rather likedhis studies than otherwise, and, indeed, took a real pleasure in someclassical authors--Homer and Horace, for example--as any lad who hasturned sixteen who has brains, and is not absolutely idle, is likely todo. He was strong, active, popular; he had passed from the purgatorialstate of fag to the elysium of fagger. But still his blood seemedturned to champagne, and his muscles to watch-springs, when the cab,which carried him and his portmanteau, passed through the gate into thedrive which curved up to the door of Holly Lodge. For Holly Lodgecontained his mother and Trix, and the thought of meeting either of themafter an absence of a school-term set his heart bounding, and his pulsethrobbing, in a way he would not have owned to his best friends for thechoice of bats in the best maker's shop. He loved his father also, buthe did not know so much of him. He was a merchant, and his business hadnecessitated his living very much abroad, while Cairo did not suit hiswife's health. His visits to England were for some years butoccasional, and did not always coincide with Harry's holidays. Twoyears previously, indeed, he had wound up his affairs, and settledpermanently at home; but he was still a busy man--a director of theGreat Transit Bank, and interested in other things, which took him up toLondon every day. He was also fond of club-life and public dinners;and, though he was affectionate with his wife and children, too much oftheir society rather bored him.

When she heard the cab-wheels crunching the gravel, Beatrice Forsyth ranout without a hat, and Harry seeing her, opened the door and "quittedthe vehicle while yet in motion," as the railway notices have it,whereby he nearly came a cropper, but recovered his balance, and wasimmediately fitted with a live necklace. Beatrice was a slight, fair,blue-eyed, curly-haired girl of fifteen; so light and springy that herbrother carried her, without an effort, to the hall steps, where, beingset down, she sprang into the cab and began collecting the smallerpackages, rug, umbrella, and other articles, inside it, while Harryhugged his mother in the hall.

"Your father will be home by four," said Mrs Forsyth, when the firstgreetings and inquiries as to health were over.

"And Haroun Alraschid has taken possession of his study," added Trix,with a sort of awe.

"Haroun, how much?" asked Harry.

"Don't be absurd, Trix!" said Mrs Forsyth. "It is only your uncle,Ralph Burke."

"Burke, that was your name, mother; this uncle was your brother then?"

"Of course, Harry. Have you never heard me speak of your uncle Ralph?"

"Now you mention it, yes, mother. But I had a sort of idea that he wasdead."

"So we thought him for some time," said Mrs Forsyth, "for he left theIndian Civil Service, in which he had a good appointment, anddisappeared for years. He met with disappointments, and had asunstroke, and went to live with wild men in the desert, and, I believe,has taken up with some strange religious notions. In fact, I fear thathe is not quite right in his head. But he talks sensibly about thingstoo, and seems to wish to be kind. We were very fond of one anotherwhen we were children, and he seems to remember it in spite of all hehas gone through."

"I am frightened to death at him," said Trix. "I know he has a largecupboard at home with the heads of all the wives he has decapitatedhanging up in a row by the back hair!"

"I wonder at your talking so foolishly, Beatrice. You must not beprejudiced by what she says, Harry. Except your uncle in Ireland, hehas no other relatives, and he may be very well off; and he is quiteharmless."

"You know that you were afraid of him yourself, mamma, when he firstcame."

"A little, perhaps, because I did not recognise him, and thought himdead. And then, you know, I fear he is not quite orthodox. But go andsee him, Harry, and never mind what any one says."

"All right, mother; you have made me a bit curious, I confess," saidHarry, leaving the room.

The garden in front of Holly Lodge was formal--just a carriage-drive,and a bit of shrubbery, and a grass-plat with prim beds on it, which hadvarious flower eruptions at different periods of the year. Firstsnowdrops, aconites, and crocuses, then tulips, then geraniums. Thereal garden was at the back, and the study looked out upon it. Not uponthe lawn, where bowls, or lawn-tennis, or other disturbing proceedingsmight be going on; no, from the oriel window, which alone lighted theroom, one saw a fountain, a statue, rose-bushes, and a catalpa tree,enclosed in a fringe of foliage, syringa, lilac, laurel, chestnut, highand thick enough to make it as private and quiet as any man with aspeech to prepare, or sums to do, might require. Harry went along apassage, turned to the left up five steps, passed through a green-baizeswing door, and knocked at that of the study.

A deep musical voice, which seemed, however, to come from a strangedistance, told him to "come in," and on opening the door, he found thathe had to push aside a curtain hanging over it, and which had dulled thesound of the voice. Smoke wreaths floated about the apartment, bearingan aromatic odour quite different from ordinary tobacco, and a curiousgurgling sound, like that of water on the boil, only intermittent, cam

efrom the direction of the broad low sofa, which had been brought fromthe drawing-room, and was placed between the fire and the window. Closeto this was a small table with writing materials, a note-book, and apile of letters ready for the post, upon it.

On the sofa reclined a man dressed in a black frock-coat, buttoned, anddark trousers, the only Oriental thing about him being the red cap witha silk tassel which he wore on his head. But smokers often have a fancyfor wearing the fez, so there was nothing peculiar in that. And yetthere was something different from other people about him. Most menlounging on a sofa are ungainly and awkward-looking, while the attitudeof this one was easy and graceful, and the motion of his hand, withwhich he indicated the chair on which he wished his nephew to be seated,was courteous and yet commanding.

His complexion was sallow, and appeared the darker from the contrastafforded by the silvery whiteness of his long beard, moustache, andthick bushy eyebrows, from the deep cavities beneath which his dark eyesseemed literally to flash. His nose was aquiline, his cheek-bonesprominent. His hands were small, but strong and nervous, with littleflesh upon them, and the fingers were long and shapely.

When Harry was seated he resettled himself on the sofa, and, keeping hiseyes fixed on the lad, placed the amber mouth-piece of a long spiraltube connected with a narghile which was smouldering on the floor to hislips, and the gurgling sound was once more produced. But to Harry'sastonishment, no cloud issued from his uncle's mouth; like a law-abidingfactory chimney, he appeared to consume his own smoke. Then,deliberately removing the amber tube which he held in his hand, hesaid--

"And you are my sister's son? I like your looks, and my heart yearnstowards you. Pity that she did not wed with one of her own land, sothat you might not have had the blood of the accursed race in yourveins. But it was the will of the All-Powerful, and what can we availagainst fate?"

What these words meant Harry could not imagine. Were not his parents ofthe same land and race? His mother was Irish and his father English,and he had no more idea of Irish, Scotch, Welsh, or English being ofdifferent races than of the inhabitants of Surrey and Essex being so.They were all Englishmen he had always thought. His bewilderment was byno means diminished when, after this speech, and without again puttingthe stem of his narghile near his mouth, his uncle raised his head andpoured out a volume of smoke, which it would have taken the unitedefforts of a couple of Germans about five minutes to produce. He wasquite veiled by the cloud, through which the gleam of his eyes seemed toHarry to have an almost supernatural effect.

"You are nearly seventeen years of age, and will soon be leavingschool," he resumed. "What are they going to do with you then?"

"I have not quite made up my mind what profession I should like," saidHarry, somewhat hesitatingly. "I am fond of drawing, and like being outof doors, and so I have thought at times of getting articled to a civilengineer."

"Ay, ay; to aid the march of civilisation, as the cant phrase goes; tobring nations closer together, that they may cut one another's throatswhen they meet. To make machines do the work by which men earn theirliving, and so first drive them into cities, and then starve them. Or,perhaps, you will be a lawyer, and learn how to darken language intoobscure terms, by which a simple, honest man may be made to sell hisbirthright without knowing what he is doing. Or a doctor, fightingmadly against the decree of the Omnipotent, daring to try to stem theflowing tide of death. If your eyes were but opened, how gladly wouldyou cast off the trammels of an effete society, and follow me to a landwhere a man can breathe freely. I will give you a horse fleet as thewind, and a sword that would split a hair or sever an iron bar, boy!"

"I have thought I should like the army, too, sir," said bewilderedHarry, trying vainly to understand, and catching at the sword and horseas something tangible.

"The army! To be a European soldier! A living machine--the slave ofslaves! To fight without a cause, even without an object! To wasteyour blood in the conquest of a country and the ruin and slaughter ofits inhabitants, and then to leave it! Madmen! Ye kill and are killedfor nothing; not even plunder."

He drew several long inhalations, repeating the conjuring trick ofswallowing the smoke and emitting it several seconds afterwards, forquite ten minutes before he spoke again.

"But the ties of home and kindred are strong," he continued in a calmertone. "Your mother, your sister, will draw you back from the noblerlot. I know what the love of family is; I, who have returned to thisseething cauldron of misery, vice, disease, and degradation which foolscall civilisation, and take a pride in, in order to see my sister oncemore. Partly for that at least. And you are her son, and you have thestamp of the Burke upon your face. Hark you, boy! In the time ofCromwell, not two hundred and fifty years ago, your direct ancestor wasa powerful Irish chief, with large domains and many brave men to followhim to battle. When the English came with the cold-blooded,preconceived scheme of pacifying Ireland once and for all by thewholesale massacre of the inhabitants, our grandsire was overpowered bynumbers, betrayed, surprised, and driven to his last refuge, a castlebut little capable of defence. He was surrounded; his wife and childrenwere with him, all young, one an infant at the breast; and there wereother women, helpless and homeless, who had sought shelter within thewalls. Therefore, resistance being quite hopeless, our chief offered tosurrender. But the English leader replied, `Give no quarter; they arewild beasts, not men. Burn up the wasps' nest, maggots and all!' Theydid it; faggots were piled round the building and set on fire, and thosewho attempted to escape were received on the English spears and tossedback into the flames. The eldest son was away with a detachment at thetime, and so escaped the fate which would otherwise have annihilated ourrace. But his estates were stolen from him and conferred on themurderers, whose descendants hold them to the present day. Have theBurkes best reason to love the English or to hate them?"

Harry Forsyth was a practical youth, who took things as he found them,and he could not even understand how anybody's feelings, much less theiractions, should be affected by anything which happened in the days ofOliver Cromwell. He might just as well refuse a penny to an Italianorgan-grinder, because Julius Caesar ill-treated the ancient Britons.Besides, he was half a Forsyth, and the Forsyths were probably allEnglish. For all he knew, some old Forsyth might have had a hand inburning up the Burkes. He did not offer any such suggestion, however,but sat somewhat awe-stricken, wondering what this strange uncle wouldsay or do next.

He relapsed into thought, and for some time the silence was only brokenby the bubbling of the water in the narghile. When at last he spokeagain, it was in a calmer tone of voice, and with eyes withdrawn fromhis nephew's face.

"Serve not the English Government, civil or military," he said. "Or, ifyou do, confine yourself to your allotted task. That which is exactlydue for the pay you receive, do for honour and honesty's sake. But dono more; show no zeal: above all, trust not to any sense of justice forreward of any work done in excess of the bargain. Incur noresponsibility, or you will be made a cat's-paw of.

"Listen. At the time of the Crimean War a young man in the Indianservice had a severe illness which obliged him to return to England onfurlough. At one of the stations where his ship touched a number ofwomen and children and invalids belonging to a regiment which had goneon to the seat of war were taken on board, and he, according to previousarrangement, was placed in charge of them.

"It came on to blow hard in the Gulf of Lyons, and the old transportstrained so that she sprang a leak, which put her fires out. Later onher masts went, and after beating about for several wretched days, shewent ashore on a desolate part of the coast of Spain. The officers andcrew of the ship behaved well enough, and though many of them, includingthe captain and chief mate, were lost, nearly all the passengers weresafely landed. But though rescued from the sea, there seemed to beevery prospect of their perishing from exposure and famine. With greatdifficulty the officer in charge managed to find some rude shelter andinsufficient food fo

r immediate succour, and then, making his way to thenearest town, he applied to the authorities, and being a linguist whoincluded something of the language in which Don Quixote was writtenamongst his acquisitions, he obtained clothes, food, and a sum of moneyfor present necessities, with the promise of a vessel to transfer theunfortunates to Gibraltar.

"Of course he had lost everything when the ship went to pieces, and hecould only get this aid by signing bills and making himself personallyresponsible. True, he was engaging himself for more than he couldperform, but he could neither desert these people who were entrusted tohis care, nor stand idly by to see them perish. And he never doubtedbut that the authorities at home would take the responsibility off hishands. They refused to do so, or rather, worse than that, they drovehim about from pillar to post, one official directing him to a second,the second to a third, the third to the first again. And they made himfill up forms, and returned them as incorrect, and broke his heart withsubterfuges.

"In the meantime he had to meet the claims, and was impoverished. Then,excited by this infamous treatment, he forced his way into a great man'spresence, and was violent, and the consequence of his violence was thathe lost his Indian appointment. It was well for him that he did so; buthis story will none the less show you what a country England is toserve."

Again there was a long period of stillness, broken only by the hubble-bubble. Gradually the smoker raised his eyes in the direction of hisnephew, but Harry saw that he was looking _beyond_ him, not at him. Andthis gaze became so steadfast and eager that he turned his head to seewhat attracted it, almost expecting to see a face on the other side ofthe window.

There was nothing, but still the intense look remained, and it madeHarry feel as if cold water was running down his back. His uncle spokeat length, low and slowly at first, more energetically as he went on.

"I see it; the crescent rises; the sordid hordes of the West fall inruin around. The squalid denizens of cities find the fiendish devicesof destruction to which they trust for putting the weak over the strongfail them. Man to man they have to stand, and they fall like cornbefore the scythe."

He dropped his pipe tube, and slowly rose to his feet, still gazingfixedly at nothing in particular in the same uncanny manner, andbringing his right-hand round towards his left hip, as if ready to graspa sword-hilt.

"One prophet," he continued, "was raised up for the destruction ofidolatry, and wherever he appeared the false gods vanished. There werethose who worshipped the True God, but received not his Prophet, andwith them Islam has for centuries waged equal war, for their time wasnot yet come, and the mission of Mohammed was not for them. But theyears of probation have expired, and the nations of the West remain inwilful darkness. They receive not the commandments of the Prophet; theydrink fermented liquor, they eat the unclean beast, their worship ofgold and science has become a real idolatry. Another prophet has arisenfor their destruction, and Asia and Africa shall, ere another generationhas come and gone, be swept clean of the Infidel. Swept clean! Sweptclean! With the scimitar for a besom!"

He remained with his eyes fixed and his lips parted, and Harry did notquite know what to do next. But he summoned courage to rise and saythat he hoped his father would have come home by now and as he had notseen him yet, he thought he would go.

Filial affection might surely be taken as a valid excuse for withdrawal.And yet, having had no experience of the etiquette due to prophets whenthe orgy of vaticination is upon them, he was not quite comfortable onthe question of being scathed. There was no need for fear; SheikhBurrachee was too rapt to heed his presence or absence. He heard nothis voice, and knew not when he crossed the room and closed the doorsoftly behind him. He found Trix in the hall looking out for him.

"Well?" she cried.

"Oh, my prophetic uncle!" ejaculated Harry.

"That is a mis-quotation."

"It is not a quotation at all; it is an exclamation, and a very naturalone under the circumstances."

"Has he been telling your fortune?" asked Beatrice, her large eyesexpanding with the interest which is begotten of mystery.

"Not exactly," replied Harry; "except that he hinted something about thepropriety of my choosing the profession of a Bedouin, and, I suppose,making a fortune by robbing caravans. But he told the misfortunes ofother people with a vengeance. The Mohammedans are going to turn theChristians out of Asia and Africa everywhere."

"Good gracious, Harry! Why, papa's a director of the Great TransitBank, and all our money is in it, and it does all its business in theEast."

"By Jove! Let us hope the prophet _doesn't know_, then. But, upon myword, he looked like seeing into futurity. At least, I could not makeout what else he was looking at."

"Poor man, he had a sunstroke when he was quite young in India, and hasled a queer life amongst savages ever since. But papa has come home andbeen asking for you. You will find him in the drawing-room."

Harry thought his father thinner and older than when he had last seenhim, and asked how he was in a more earnest and meaning manner than iscustomary in the conventional "How do you do?"

"Do I look altered?" asked Mr Forsyth, quickly.

"Oh, no, father, only a little pale; tired-looking, you know," saidHarry, rather hesitatingly, in spite of the effort made to speakcarelessly.

"I have not been quite the thing, and have seen a physician about it.Only a little weakness about the heart, which affects the circulation.But do not mention it to your mother or sister; women are so easilyfrightened, and their serious faces would make me imagine myselfseriously ill. Well, how did you get on with your uncle? You see hehas turned me out of my private den."

"Is he at all--a little--that is, a trifle cracked, father?"

"A good deal, I should say. And yet he is a very clever man, andsensible enough at times, and upon some subjects. He was most useful tome out in Egypt on several occasions when we happened to meet. A greattraveller and a wonderful linguist."

"Was he badly treated by Government? He told me a story in the thirdperson, but I expect that he referred to himself all the time," saidHarry.

"Well," replied Mr Forsyth, "it is difficult to tell all the rights ofthe story. Ever since he had an illness in India, as a very young man,he has been subject to delusions. No doubt he behaved well on theoccasion of a certain shipwreck--if that is what you allude to--andincurred heavy expense, which ought to have been made up to him. But Idoubt if he went the right way to work, and suspect that his failure wasdue very much to impatience and wrong-headedness, and the mixing up ofpolitical questions with his personal claims. He wrote a book, whichmade some noise, and caused him to lose his appointment. Then he cameto me in Egypt, and was very useful.

"I should have liked him for a partner, but he went off to discover thesource of the Nile. He thought he had succeeded, and after adisappearance of some years came back triumphant. But he had followedthe Blue Nile instead of the real branch, and the discoveries of Speke,Grant, Livingstone, and Stanley were terribly bitter to him--drove himquite mad, I think. Since then he has identified himself with the Arabrace, and seems to hate all Europeans, except his sister and her family.With me he has never quarrelled, and I think remembers that I offeredhim a home and employment when his career was cut short. What he is inEngland for now I do not know. Perhaps only to see your mother oncemore, but I suspect there is something else.

"He writes many letters, and makes a point of posting them himself. Ifear that he takes opium, or some drug of that kind, and altogether,though it is inhospitable perhaps to say so, it will be a relief when heis gone, and that will not be many days now."

After leaving his uncle in such a rapt state, it was curious to Harry tosee him walk into the drawing-room before dinner in correct eveningcostume, and not wearing his fez. He was somewhat taciturn, ate verylittle, and drank nothing but water, but his manners were those of aperfect gentleman. After dinner he retired, and they saw no more of himthat evening.

Harry Forsyth had several other interviews with his uncle, who showedmore fondness for his company than he had for that of any other memberof the family, but who kept a greater guard over himself, and was morereticent than he had been on the occasion of his first interview. Hespoke of Eastern climes, war, sport, and scenery, with enthusiasmindeed, but rationally, and Harry grew interested, and liked to hearhim, though he never got over the feeling that there was somethinguncanny about him.

One night, after dinner, when a fortnight of Harry's holidays hadelapsed, the uncle, on retiring, asked his nephew to come and see him inthe study at eleven on the following morning, and Harry, punctuallycomplying, found him seated on a chair before the large table with threepackets before him.

"Sit down, my lad," he said, and the deep musical tones of his voice hadan affectionate sadness in them.

"I am going back to my own land to-morrow, and shall never leave itagain. But we shall meet, for such is the will of the All-Powerful,unless the inward voice deceives me, as it has never hitherto done. Youwill, or let us say you _may_, need my aid. You will learn where andhow to find the Sheikh Burrachee--which is my real name--from Yusuff,the sword dealer, in the armourers' bazaar, at Cairo. But you will morecertainly do so by applying to the head Dervish at the mosques ofSuakim, Berber, or Khartoum. At the last town, indeed, you will have nodifficulty in learning where I am, and being conducted to me; and,indeed, in any considerable place above the second cataract of the Nile,you will probably learn at the mosque how and where to obtain therequired direction, even if they cannot give it you themselves. Ifthere is hesitation, show the holy man this ring, and it will be removedat once. Should you meet with hindrance in your journey from any deserttribe, ask to be led to the chief, and give him this parchment. He maynot be an ally to help you, but he may, and if not, he will probably nothinder you. Lastly, take these three stones, and see that you keep themsecurely in a safe place, and that no one knows that you possess them.They are sapphires of some value I exact no promise, but I bid you notto part with these for any purpose but that of coming to me. For that,sell them. Should you hear of my death, or should ten years elapsewithout your coming to me, they are yours to do what you like with.Lest you should forget any part of my directions, I have written them ona paper which is at the bottom of the box containing the sapphires.Come."

Harry rose and stood by his side. His uncle fitted the ring on hisfore-finger, put the morocco box containing the sapphires, and the thinsilver case, like a lady's large-sized card-case, that protected thewritten document, into his breast pocket, and then rising himself,rested his two hands on the lad's shoulders, and gazed long andearnestly into his face.

Then turning his eyes upwards, he muttered a prayer in Arabic, afterwhich he gently drew him to the door, and, releasing him, opened it, andsaid, "Farewell."