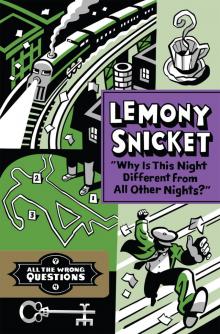

Why Is This Night Different From All Other Nights?

Lemony Snicket

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

Copyright Page

In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher is unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

TO: B., P. Bellerophon

FROM: LS

FILE UNDER: Stain’d-by-the-Sea, accounts of; murder, investigations of; Hangfire; Bombinating Beast

4/4

cc: VFDhq

CHAPTER ONE

There was a town, and there was a train, and there was a murder. I was on the train, and I thought if I solved the murder I could save the town. I was almost thirteen and I was wrong. I was wrong about all of it. I should have asked the question “Is it more beastly to be a murderer or to let one go free?” Instead, I asked the wrong question—four wrong questions, more or less. This is the account of the last.

I was in a small room, not sleeping and not liking it. The room was called the Far East Suite, and it sat uncomfortably in the Lost Arms, the only hotel in town. It had a chest of drawers and a little table with a metal plate that was responsible for heating up a number of very bad meals. A puzzling shape on the ceiling was someone’s idea of a light fixture, and a girl on the wall, holding an injured dog, was someone else’s idea of a painting. There was one window and one shutter covering it, so the room was far too dark except in the morning. In the morning it was far too light.

But most of the room was a pair of beds, and most of what I didn’t like slept in the larger one. Her name was S. Theodora Markson. I was her apprentice and she was my chaperone and the person who had brought me to the town of Stain’d-by-the-Sea in the first place. She had wild hair and a green automobile, and those are the nicest things I could think of to say about her. We’d had a fight over our last big case, which you can read about if you’re the sort of person who likes to know about other people’s fights. She was still mad at me and had informed me I was not allowed to be mad at her. We had not talked much lately, except when I occasionally asked her what the S stood for in her name and she occasionally replied, “Stop asking.” That night she had announced to me that we were both going to bed early. There is nothing wrong with an early bedtime, as long as you do not insist that everyone has to go with you. Now her wild hair lay sprawled on the pillow like a mop had jumped off a roof, and she was snoring a snore I’d never heard before. It is lonely to lie on your bed, wide awake, listening to someone snore.

I told myself I had no reason to feel lonely. It was true I had a number of companions in Stain’d-by-the-Sea, people more or less my own age, who had similar interests. Our most significant interest was in defeating a villain named Hangfire. My associates and I had formed an ad hoc branch of the organization that had sent me to this town. “Ad hoc” means we were all alone and making it up as we went along. Hangfire worked in the shadows, scheming to get his hands on a statue of a mythical creature called the Bombinating Beast, so my friends and I had also started to keep our activities quiet, so that Hangfire would not find out about us. We no longer saw each other as much as we used to, but worked in solitude, in the hopes of stopping Hangfire and saving Stain’d-by-the-Sea.

The distant whistle of a train reminded me that so far my associates and I hadn’t had much success. Stain’d-by-the-Sea was a town that had faded almost to nothing. The sea had been drained away to save the ink business, but now the ink business was draining away, and everything in town was going down the drain with it. The newspaper was gone. The only proper school had burned down, and the town’s schoolchildren were being held prisoner. Hangfire and his associates in the Inhumane Society had them hidden in Wade Academy, an abandoned school on Offshore Island, for some reason that was surely nefarious, a word which here means “wicked, and involving stolen honeydew melons and certain equipment from an abandoned aquarium.” The town’s only librarian, Dashiell Qwerty, had been framed for arson, so now the town’s only police officers would take the town’s only librarian out of his cell and put him on the town’s only train, so he could stand trial in the city.

You know who else is in the city standing trial, I told myself, but thinking about my sister didn’t make it any easier to get to sleep. Kit had been caught on a caper when I was supposed to be there helping her. I felt very bad about this, and kept writing her letters in my head. The preamble was always “Dear Kit,” but then I had trouble. Sometimes I promised her I would get her out, but that was a promise I couldn’t necessarily keep. Sometimes I told her that soon she would be free, but I didn’t know if that was true. So I told her I was thinking of her, but that felt very meager, so I kept crumpling up these imaginary letters and throwing them into a very handsome imaginary trash can.

And then there’s the one, I thought, who has stolen more sleep from you than all the rest. Ellington Feint, like me, was somewhat new in town, having come to rescue her father from Hangfire’s clutches. She’d told me that she would do “anything and everything” to rescue him, and “anything and everything” turned out to be a phrase which meant “a number of terrible crimes.” Her crimes had caught up with her, and now she was locked in Stain’d-by-the-Sea’s tiny jail. The train is coming for her too, I told myself. Soon she will be transported through the outskirts of town and down into the valley that was once the floor of the ocean. She will ride past the Clusterous Forest, a vast, lawless landscape of seaweed that has managed to survive without water, and you might never see her again.

So many people to think about, Snicket, and still you are all alone.

The whistle blew again, louder this time, or perhaps it just seemed louder because Theodora’s odd snoring had stopped. It had stopped because it wasn’t snoring. She’d been pretending to be asleep. I closed my eyes and held still so I could find out why.

“Snicket?” she whispered in the dark room. “Lemony Snicket?”

I didn’t make a sound. When pretending to be asleep, you should never fake snoring in front of people who may have heard your actual snores. You should simply breathe and keep still. There are a great number of circumstances in which this strategy is helpful.

“Snicket?”

I kept still and kept breathing.

“Snicket, I know you’re awake.”

I didn’t fall for that old trick. I listened to Theodora sigh, and then, with a great creaking, she got out of bed and pattered to the bathroom. There was a click and a small stripe of light fell across my face. I let it. Theodora rustled around in the bathroom and then the light went out and she walked across the Far East Suite with her feet sounding different than they had. She’d put on her boots, I realized. She was going out in the middle of the night, just when the train was coming to a stop.

I heard the doorknob rattle and quit. She was giving me one last look. Perhaps I should have opened my eyes, or simply said, suddenly in the dark, “Good luck.” It would have been fun to startle her like that. But I just let her walk out and shut the door.

I decided to count to ten to make sure she was really gone. When I reached fourteen, she opened the door again to check on me. Then she walked out again and knocked the door shut again and I counted again and then one more time and then I stood up and turned the light on and moved quickly. I was at a disadvantage because I was in my pajamas, and it took me a few moments to hurry into clothing. I put on a long-sleeved shirt with a stiff collar

that was clean enough, and my best shoes and a jacket that matched some good thick pants with a very strong belt. I mention the belt for a reason. I walked quickly to the door and opened it and looked down the hallway to make sure she wasn’t waiting for me, but S. Theodora Markson had never been that clever.

I looked back at the room. The star-shaped fixture shone down on everything. The girl with the dog with the bandaged paw gave me her usual frown, as if she were bored and hoped I’d give her a magazine. Had I known I was leaving the Far East Suite behind forever, I might have taken a longer look. But instead I just glanced at it. The room looked like a room. I killed the lights.

In the lobby were two familiar figures, but neither of them was my chaperone. One was the statue that was always there in the middle of the room, depicting a woman with no clothes or arms, and the other was Prosper Lost, the hotel’s proprietor, who stood by the desk giving me his usual smile. It was a smile that meant he would do anything to help you, anything at all, as long as it wasn’t too much trouble.

“Good evening, Mr. Snicket.”

“Good evening,” I told him back. “How’s your daughter, Lost?”

“If you hadn’t decided to go to bed early, you would have seen her,” Prosper told me. “She stopped by to visit me, and left something for you as well.”

“Is that so?” I said. Ornette Lost was one of my associates, and for reasons I didn’t quite understand, she lived with her uncles, Stain’d-by-the-Sea’s only remaining firefighters, instead of with her father.

“That is so,” her father said now, and reached into his desk to retrieve a small object made of folded paper. I picked it up just as the whistle blew again.

It was a train.

“Ornette’s always been good at fashioning extraordinary things out of ordinary materials,” Lost said. “I suppose it runs in the family. Her mother had a great interest in sculpture.”

“Did she?” I said, although I was not really listening. When someone leaves a folded paper train for you, you take a moment to wonder why.

“She did indeed,” Lost said. “Alice had an enormous collection of statues and a great number of her own sculptures as well. They were displayed in the Far West Wing of this very hotel. My wife hoped the glyptotheca would attract tourists, but things didn’t go as planned.”

“They hardly ever do,” I said. “Glyptotheca” is a word which here means “a place where sculpture is displayed,” but I was more interested in unfolding the train. It had been constructed out of a single business card. All my associates in Stain’d-by-the-Sea had cards nowadays, printed with their names and areas of specialty. My eyes fell on the word “sculptor.”

“Most of the statues were destroyed in a fire some time ago,” Lost said. “Ornette was the one who smelled the smoke, which runs in the family too. By the time her uncles arrived to fight the fire, my daughter had managed to rouse the entire hotel and help the guests and staff to safety. Everyone was rescued—everyone but Alice.”

I stopped looking at what was in my hands and stared into the sad eyes of Prosper Lost. I had always found the hotel where I had been living, and the man who ran it, to be shabby and uncomfortable. Not until now had I thought of either of them as damaged. “I’m sorry,” I said. “I didn’t know.”

“I didn’t tell you,” Lost said, with his faint smile. “I suppose we all have our troubles, don’t we, Snicket?”

“Mine are smaller than yours, Lost.”

“I’m not so sure about that,” Lost said quietly. “It seems to me we’re in the same situation, both alone in the lobby.”

“So you saw my chaperone go out?”

“Yes, just a minute ago.”

“Did she tell you where she was going?”

“I’m afraid not.”

“Did she say anything at all?”

Prosper Lost shifted slightly. It must have been tiring for him to stand up at the desk, but I don’t think I’d ever seen him sit. “Actually,” he said, “she told me that if she didn’t return by tomorrow, I ought to make sure you were provided for.”

“What?”

“She told me that if she didn’t return—”

“I heard you, Lost. She said she wasn’t coming back.” My chaperone had once told me she was leaving town, but our organization did not permit leaving apprentices unsupervised. I looked at the train again, fashioned out of a card that was designed for communication. But what is Ornette communicating, I asked myself. Myself couldn’t answer, so I asked somebody else something else. “How long does the train stop at the station?”

“Oh, quite a while,” Prosper said, with a glance at his watch. “The railway switches engines at Stain’d-by-the-Sea, and it takes a long time to load in all the passengers. It seems there are always more and more people who want to get out of town.”

“Listen, Lost,” I said. “If I don’t return by tomorrow, will you do something for me?”

“What is it?”

“There’s a book beside my bed,” I said. “If I’m not back, please give it to the Bellerophon brothers.”

“The taxi drivers?” he said. “All right, Snicket. If you say so. Although I’m surprised you’re not bringing the book along. It seems to me that you always have a book with you.”

“I do,” I said, “but this book belongs to the library.”

“The library was destroyed, Snicket. Don’t you remember?”

“Of course I remember,” I said, “but I still shouldn’t take it with me. It’s too bad, too. I’m only partway through.”

“So it goes,” Prosper Lost said, a little sadly. “There are some stories you never get to finish.”

I nodded in agreement and I never saw him again. Outside, the night was colder than I would have guessed, but not colder than I like it. I headed toward the train station, thinking of the book. It was about a man who went to sleep one night, and when he woke up he was an insect. It was causing him a great deal of trouble. The streets were quiet and I went several blocks, all the way to the town’s last remaining department store, before I saw a single person.

Diceys was a tall building that looked like a neatly stacked pile of square windows, catching the starlight and winking it back at the sky. In each window was a mannequin dressed in Diceys clothes, posed with some item or other that the store had for sale. Diceys was closed at this time of night, but a few lights were still on inside, and the mannequins stood eerily looking down at the store’s large entrance, a fancy door chained shut with a padlock as big as a suitcase. Struggling with the lock was S. Theodora Markson. Her efforts to unlock Diceys were fierce and required both her hands and occasionally a foot, and her bushy hair waved back and forth as she tried to wrestle her way into the store. From across the street she almost looked like an insect herself, as frantic and frightened as the man in the book. What happens next, I thought.

Finally, Theodora persuaded the door to open and slipped inside Diceys. I waited just a few seconds before slipping after her. I didn’t move too carefully. Anyone who struggles endlessly with a lock on a public street is not worried about being followed. There was a large, spiky metal object stuck in the lock. It was a skeleton key, but not a good one. A good skeleton key can open any lock at any time. A bad one can open some locks, some of the time, after much struggle. I looked at it, but only for a second, because I had seen it before. It was likely the only one in town. I left it where it was. I had no skeleton key as I stepped inside Diceys. I had only the clothes on my back, and a small folded paper train in my hand. My chaperone had something better. She had a secret.

CHAPTER TWO

Diceys was dark. I entered where perfume was sold, with glass bottles waiting on shelves like a laboratory with the mad scientist on vacation. I scanned the large room I was in. Nothing moved in it but a small light on a far wall. I made my way. The bottles watched me. I never have liked perfume. It always smells like someone’s been hit by a truck full of flowers.

The light on the wall was over the e

levator doors, indicating that the elevator was moving. The light marked 4 turned on, and then the one marked 5. Theodora was going up. There was another elevator, but I couldn’t risk taking it. I waited to see where it stopped. Then I’d take the stairs. I hoped it would stop soon. It stopped at 11.

The staircase was a fancy one, very wide, with banisters that were probably brass and carpeting that was probably red when the lights were on. With the lights off, the banister was just smudgy and the carpeting was dotted with light lint and dark stains. At each turn of the staircase was a sign telling me what they sold on the floor. The second floor sold shoes for men. The third floor sold shoes for women. The fourth floor also sold shoes for women. The fifth floor sold housewares, with radios and mixing bowls casting shapely shadows on the walls. The sixth floor sold toys, and I thought of a book for small children as I paused to catch my breath. A bear wanders a department store at night, looking for a button he has lost. He’s caught by the night watchman. Diceys probably doesn’t have a night watchman, I told myself. If they can’t afford to polish the banisters, they can’t afford to pay a man to watch over the place. They just lock the door and go home. In any case, you’re not the one who broke in. Theodora broke in. You’re just following her. So stop leaning against the banister and follow her.

The seventh floor sold formal clothing. The eighth sold casual clothing. The ninth sold children’s clothing, and I remembered Theodora taking me there some weeks back, to be measured for new pants. It is embarrassing to be measured for new pants. The tenth floor sold the bright, shiny clothing people apparently enjoy wearing to play sports.

The eleventh floor sold uniforms. One of the advantages of the organization to which Theodora and I belonged was that there were no uniforms, unless you count a small tattoo on the ankle. I walked quietly between the racks of matching clothing hung up like flattened women and men, and wondered what Theodora was doing there. But she didn’t seem to be there at all. Aisle after aisle of uniforms was empty. I looked this way and that. The uniforms shrugged back at me. Finally I reached the far end of the eleventh floor, where the windows looked down on the street. There was a mannequin dressed like a police officer in one window, and one dressed as a firefighter in the next. Then there was a uniformed nurse, and a cook, and a sailor, and then, standing in a window, there was a mannequin wearing nothing at all. At its feet were a pile of clothes I recognized as Theodora’s. She had stood right there and changed her clothing, putting on whatever uniform had been worn by the mannequin. I did not like to think about it. I was at least relieved that Theodora’s underwear was not in the pile, so she had not been completely naked in the window of a department store.