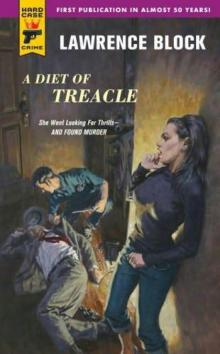

A Diet of Treacle

Lawrence Block

A Diet of Treacle

Lawrence Block

To all stoop-sitters, everywhere…

“Once upon a time there were three little sisters,” the Dormouse began in a great hurry; “and their names were Elsie, Lacie, and Tillie; and they lived at the bottom of a well—”

“What did they live on?” said Alice, who always took a great interest in questions of eating and drinking.

“They lived on treacle,” said the Dormouse.

“They couldn’t have done that, you know,” Alice gently remarked. “They’d have been ill.”

“So they were,” said the Dormouse. “Very ill.”

—from ALICE IN WONDERLAND

Contents

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

A New Afterword by the Author

A Biography of Lawrence Block

1

Joe Milani studied the room with half-open eyes. He spent a long time absorbing every aspect of the interior of the coffee-house with the intensity of a person who had never been there before and who might never return. At last he rested his gaze on the small cup of coffee in front of him with the same concentration. And he decided that the coffee-house was the most logical spot in the world for him.

Item one: the name of the place was The Palermo—after the city in which his grandfather had been born.

Item two: the coffee-house had a Bleecker Street address—the street on which his father had been born.

Item three: the coffee-house belonged to the fringe of Greenwich Village—where all the world’s misfits were supposed to live. And he thought that he, Joe Milani, one of humanity’s round pegs, had found the world the squarest of holes.

He laughed to himself, pleased at his play on words. Then, chopping off his laugh as suddenly as he had started it, he raised the demitasse of espresso to his lips. He took a sip, savoring the thick, black liquid. Thirty cents was what The Palermo picked up for a cup of espresso, thirty cents for a squirt of ink, thirty shining coppers for a less-than-respectable swallow of liquid mud. Joe’s grandfather, who might well have sipped espresso in the same chair before coffee-houses had become fashionable, had probably paid a nickel for the slop.

Thirty cents. But, Joe reflected, as he swallowed the coffee, that gummy concoction was worth it. If you were stoned, that is.

Stoned. He was that. Stoned, smashed, blind, turned on and flying so high and so cool and everything so just exactly right.

Softly he sang:

Every time it rains, it rains

Sweet marijuana.

I grow pot in my backyard,

Sweet marijuana.

Sweet marijuana.

I blow up in my garage

Any time I wanna…

Joe Milani looked across the table at Shank to see if the guy was digging the song, if the thin boy of the intense black eyes and the straight black hair would nod and mumble and laugh with him. But Shank was cooling it, his eyes shut, his hand supporting his chin. Shank, stoned, was listening in to something and digging something—maybe some music he had heard weeks ago or a chick he had balled or maybe nothing but his own private thoughts.

Joe took another bite out of the espresso, marveling at the way everything tasted so much better when you were high. It was as if you were getting the whole taste, inside and out, and as if, were you to close your eyes, you could see what you were eating. He felt that his lips tasted the coffee, and then flipped the liquid to his tongue and palate; and then, when he swallowed it he was convinced that his throat could taste the coffee as it made its way to his stomach. He finally finished the espresso and leaned back against the wrought iron chair, his eyelids low and his hands motionless in his lap. He was tuning in on himself.

Deliberately he concentrated on his right hand. He could see the hand vividly in his mind, the dark curling hairs on its back, the whorls on the fingertips. He could feel the pulse in his hand, and the blood moving through the palm into the fingers. His hand grew very heavy, throbbing as he concentrated on it.

Joe shifted his concentration from one part of his body to another, and each time the effect was the same. His heart pounded and was bright red in his mind’s eye. His lungs swelled and flattened as he breathed in and out.

Cool.

So cool…

How long had it been? Two joints a few minutes after noon, two joints he and Shank had split, two little cigarettes hand-rolled in wheat-straw paper and smoked rapidly, had been passed back and forth between them until there had been nothing left but two roaches, two tiny butts that they had stuffed into the hollowed-out ends of regular cigarettes and had smoked the same way. Just two joints—and they had gotten so stoned, so fly, that it seemed now as if the high were going to go on forever.

With an effort Joe pushed open his eyes and straightened up in the chair. The good thing about pot was that you could turn yourself on and off and on again and never lose control—unlike beer or wine or whiskey that rocked you only to dull everything finally. And pot had it all over heroin or morphine or cocaine—the hard stuff that sent you on the nod and left you in a fog until it wore off and you were down on the ground.

No, Joe Milani weightily concluded, pot was so much better. No habit, no hangover, no loss of control. And it didn’t take more and more of the stuff to get you high each time, no matter what the books said, because the books were all written by people who didn’t know, people who hadn’t been there. Joe had been there, and he was there right now, and he knew.

And he idly wondered what the time would tell him. There was a clock on the wall behind the cash register. By squinting, he could just about make out the numbers—nearly 3:30, which meant that he had been high for better than three hours on two little joints. And the three hours felt like at least six, because when you were high you noticed everything that was happening and the time crawled by and let you stroke it on its furry back.

He glanced at Shank, who hadn’t moved since Joe’s benevolent eye had last fallen on him. Then Milani gazed around the coffee-house again—and saw the girl.

She was extremely pretty. Joe dwelled a long time on the girl, taking careful note of the brown hair verging on black, long lovely hair falling very neatly to her shoulders. He studied the full mouth slightly reddened by lipstick, and the clean, small hands whose slender fingers curled around the sides of a cup of cappuccino. Her enormous eyes were enhanced by a clear and lightly tanned complexion, and her bare forearms, covered by downy hair, were neither too heavy nor too thin. Joe searched her face, hoping she wouldn’t turn toward him while he examined her. He tried to see through her, into her.

She appeared to be out of place in The Palermo. Her simple attire of white blouse, dark green skirt and flats was appropriate enough for a Villager, but there was an aura about her that made Joe certain she didn’t live in the area.

She was hardly more than a few tables away from him, sitting alone at the window, and doing nothing but looking pretty. But doing that quite well indeed. Joe leaned across the table and shook Shank by the shoulder. At first he aroused no response; then Shank’s eyes slitted and his features assumed a what-the-hell-is-it-now expression.

“Man—” Joe Milani began.

“Yeah?”

“Dig.” Joe nodded in the direction of the girl. Shank flicked, then turned back.

“The chick?” Shank barely made the question.

Joe managed his head up and down a half inch either way.

“What about her?”

“Watch, man. I’m going to pick her up.”

Shank took in the sight of the girl agai

n, more closely this time. Then he shrugged.

“You won’t make it, man,” he said.

“You don’t think so?”

Shank shook his head slowly, his eyes dreamy, his face completely relaxed again. When he spoke, the words were spaced wide apart and enunciated precisely, as if he were rolling each syllable on his tongue in order to taste it.

“Never, man. She is a pretty chick and like that, but she is also a very square chick and she will put you into the ground if you so much as say hello to her. She will put you down so hard you will have to crawl back to the table, man. On your knees, like.”

Joe giggled softly.

“Go ahead,” Shank said. “Try, if you have eyes. But you won’t make it.”

“Look, I’m stoned, Shank.”

“So what?”

Joe giggled again. “Don’t you dig, Shank? I’m blind, and when I’m blind I become very cool. I say everything just right and I play everything off the wall and I never strike out, man. I’m just so cool.”

He repeated “cool,” dragging out the word so he could feel just how cool he was, how clear-headed and icily calm.

“You just think you’re cool,” Shank said. “You’ll scare the girl, baby. You’ll scare her and she’ll put you down.”

“Why do you put it there?

“That’s where it’s at.”

Joe smiled, a lazy smile. “Bet me,” he said. “Bet me I don’t pick her up.”

“What do you want to bet?”

He considered. “Bet me a joint,” he offered.

“A joint?”

Joe nodded.

“Cool,” Shank said. “I got a joint you don’t get to first base.”

“You’ll lose the bet, baby. Us wops never lose a bet, you know. Especially when we’re high.”

He did not wait for Shank to reply. Instead, he stood up, light on his feet, calm. He was extremely sure of himself, sure he was tall and good-looking enough to attract her, sure he would come on strong enough to interest her. He was twenty-seven, which meant he had a good five years on the girl at the very least, and he was a little more than six feet tall—wide-shouldered, narrow-waisted and muscular. He rubbed the palm of one hand over his cheek, glad he had taken the trouble to shave this morning.

But he wasn’t dressed very well, he realized—just dirty chinos and a t-shirt. Besides, his crew-cut had grown out to the point where he ought to start combing it or have it cut again. But he felt so cool, so utterly cool, that all the rest didn’t matter.

He walked to the girl’s table, slowly, easily, his eyes fixed on her face. She did not peer up, not even when he stood over her to stare down at her so intensely he was certain she must have been aware of his presence. Then he drummed a tattoo on the table-top. Startled, she raised her eyes.

“Hello,” he said, pleasantly. “Is your name Bernice?”

A second or two elapsed before she could reply. At last she shook her head rapidly.

“I didn’t think it was,” he said. “Neither is mine.”

She said nothing, her expression one of bewilderment.

“You look awfully familiar,” he said, pushing onward. “Have you ever been in Times Square?”

“Why I—”

“Great place, Times Square. Did you ever stop to think that there’s a phrenology parlor on Eighth Avenue that opens at 4:30 in the morning?”

Wide-eyed, lips parted, she seemed prettier than ever.

“I know what you’re doing,” he confided. “You’ve got the rest of these people fooled but I’m wise to you. They think you’re just drinking a cup of cappuccino but I know for a fact you’re planning the Portuguese invasion.”

He waited for that to sink in, wondering at the same time what in the world he was talking about. Then he flashed her a great smile and fastened one hand on the chair opposite her. She tried to say something but he beat her to it, timing everything with intuitive flawlessness.

“You’re very pretty,” he said, “even if your name isn’t Bernice and you’ve never been to Times Square and you don’t happen to be planning the Portuguese invasion. You don’t mind if I sit down, do you?”

For a moment she gave the impression of speechlessness, as if lost somewhere in left field, he thought, and he was on the point of sitting down without waiting for a reply when she finally managed utterance.

“Go ahead,” she said. “I mean…you probably would anyway, wouldn’t you?” He pulled back the chair and sat down, longing to glance at Shank triumphantly. Instead, he smiled at the girl.

“If you’re name isn’t Bernice, what is it?” Joe Milani inquired.

“Oh,” she said. “It’s Anita.”

“Hello, Anita.”

“Hello.”

“Do you live here in the Village, Anita?” He knew that she didn’t but it was as good a question as any.

“No, I’m just visiting.”

“Where do you live?”

“Uptown.”

“Uptown,” he said, “takes in a lot of ground.”

“116th Street between Second and Third.”

“Yeah? Way up in wop Harlem?”

She stiffened.

“What’s the matter?” He put the question with some concern.

“Do you have to use that word?”

“What word?” It was hard to avoid laughing but he made it.

“Wop,” she said softly. “I don’t like that word.”

This time he let himself smile. “I am called Joseph Milani,” he said in perfect Italian. In English he added, “So it is all right if I use the word?”

Anita, by now off-balance, was attempting to say something but she obviously had not the slightest idea of what it should be, so her mouth moved soundlessly. Confidently, he reached out a hand and let the fingertips touch hers.

She neither drew away nor flinched.

He examined her again. He decided her body was exceptionally good, decidedly not a trial to behold, a little on the slender side but starring breasts firm and well-shaped.

Joe considered he had her practically hypnotized. He said a silent prayer of thanks to the pot, flashed her a smile showing his white teeth, and pressed her fingers gently.

“Anita,” he said, “The Palermo is a pleasant place, but it’s too hot and too stuffy and too limited. Let’s make it.”

“Make it?”

“Split,” he said. “Cut out. Leave.”

“Oh.”

“Come on,” he said. He stood up; mesmerized, she stood up, too. He waited while she paid her check. Then she rejoined him, and he took her hand in his. Her hand felt very soft, but he resisted the temptation to give it a gentle squeeze. Leading her out of the coffee-house, he glanced at Shank.

But Shank was in another world, his head lolling back, his eyes veiled, and one hand lying limp on the table before him like a discarded napkin.

2

Leon Marsten, whom nobody had called anything but Shank for the last four years, sat up abruptly at four-seventeen P.M. and blinked rapidly. He fumbled for a cigarette and lit it. Laboriously, he dragged smoke into his lungs and held it there. He blew it out slowly in a long, thin column that floated languidly toward the ceiling. When he finished the cigarette, he dropped it and elaborately ground it into the linoleum with the heel of his tennis shoe until it was completely shredded. The ritual completed, he turned and methodically surveyed the coffee shop. Satisfied that nobody was watching him, he stood up and strode out the door onto Bleecker Street.

To hell with The Palermo, he thought—the coffee was on the house for a change.

He walked west on Bleecker, moving quickly but not really in a hurry. At Macdougal Street he turned uptown and walked past coffee-houses and restaurants and gift shops toward Washington Square Park. Once in the park, he paused to drink at the water fountain. A little later, he stopped again to buy an ice cream sucker from one of the Good Humor Men haunting the Square, and resumed his stride as he ate his ice cream.

He h

alted at an empty park bench near the circle at the foot of Fifth Avenue, and sat down. From the back pocket of his dungarees he pulled a paperback novel. He relaxed on the bench and turned the pages of the book.

Shank was twenty years old. He had been born a little more than twenty years before to Jeff and Lucy Marsten who, not long after the boy’s birth, had mutually agreed to a divorce. Jeff Marsten had then married a girl named Susan Lockridge, the two remaining in El Cajon, California, while Lucy and her son had moved to Berkeley where, in no time at all, Lucy had once again become a bride, this time to a Mr. Bradley Galton. Shortly thereafter, Mr. and Mrs. Galton, son Leon in tow, had pulled up stakes to settle in Los Angeles.

But Leon—Shank—had developed an instant and abiding dislike for the fat and ruddy Bradley Galton. Shank had tried to compensate for his deepening hatred toward his stepfather by intensifying what he had at first felt to be love for his mother; but Shank’s love evidently could not have run too deep, because the fact that his mother had married Bradley had been enough to mock the boy’s desire to feel more affectionate toward her, and the more he had thought about that, the less delight had he felt in her presence. And after she had given birth to a baby girl, Cindy, Shank could feel no affection for his mother at all.

For that matter, Shank had not liked anybody, not until much, much later.

He grew up alone, a quiet, moody boy who went his own way and thought his own thoughts. He was more clever than intelligent, but his grades in school concealed the fact neatly. School was a challenge for him, not to work, but to avoid work and cause trouble. In the beginning he displayed no particular imagination at causing trouble. When he played with other children, in the days when there were still other children who would play with him, he broke their toys or fought with them or beat them up. He was always short and always thin, but his wiry frame and superb coordination won him every fight. On the other hand, it should also be mentioned that he never took on a fight unless he could count on victory.

Growing older, he grew more inventive. All through grammar school, Halloween was a special treat for him, but he never played the game the way it was supposed to be played. The other children in the neighborhood gave homeowners the option of trick-or-treat; Shank dispensed with the treats and soaped windows. That was the first year. The second year he observed Halloween he realized that playing the trick did not have to rule out the treat. He collected a huge bagful of candy that year. He also broke fifteen windows and slashed two tires with a paring knife he stole from the kitchen.