Crossing the Horizon

Laurie Notaro

Thank you for downloading this Gallery Books eBook.

* * *

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Gallery Books and Simon & Schuster.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

To Elsie Mackay, Mabel Boll, Ruth Elder, Captain Ray Hinchliffe, George Haldeman, Charles Levine, and their families.

To Pamela Hinchliffe Franklin and Joan Hinchliffe, with enormous gratitude and great fondness.

All of your horses invariably galloped.

The American Girl.

PROLOGUE

CHRISTMAS EVE 1927

After the final plane check before her aircraft would take off, Frances Wilson Grayson, the niece of President Woodrow Wilson, addressed the crowd of reporters before her.

“All my life, Christmas has been the same,” the stout and ruddy Grayson said. “The same friends, the same gifts that didn’t mean anything. Telling people things you didn’t mean. But this year will be different.

“All Lindbergh did was fly an airplane, and look at all the publicity he got,” she announced. “We’re finally going to fly the Atlantic. I’ll be famous!”

She was determined that nothing could stop her from charging into her place in history. Not the weather, not the crew, and certainly not the other women who pined for the title that would be hers in a matter of hours.

She would be the first woman to cross the Atlantic in an airplane. The first. The only.

It would not be the English heiress, Elsie Mackay; the idiotic Ruth Elder; or the taudry Mabel Boll. All of them wanted what she was just about to reach and take for herself. She was sure it would be hers.

Then she pulled a pistol out of her pocket and waved it over her head.

Reporters and bystanders ducked and shielded themselves with their hands, not sure if it was a joke or if it was a real gun.

“This time”—she smiled—“there will be no turning back.”

CHAPTER ONE

SPRING 1924

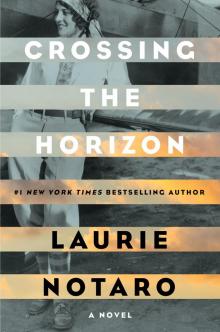

Elsie Mackay, 1920.

Hang on, she told herself as she tightened her grip as much as she could, the wind screaming wildly in her ears. Her eyes were closed; she knew that she should not open them. She was a thousand feet in the air, but right now all she had to do was hang on. That’s all, she said to herself again, this time her lips moving, her eyes squeezing tighter. Just hang on.

Twenty minutes before, the Honourable Elsie Mackay had sped up to the airfield, parked her silver Rolls near the hangar, the dirt cloud of her arrival still lingering in the air. She opened the side door to let Chim, her affectionate tan and white Borzoi, out to run the field. Suited up and goggled for a run with Captain Herne, her flying instructor, she was anxious to get back up into the air. The splendor and alchemy was consuming, swallowing her whole every time she lifted off the ground, dashing through clouds and soaring far above the rest of those anchored below. She had been enchanted at the controls of an airplane, feeling charged and elated—something she had almost forgotten. It had been weeks since she’d been up.

Captain Herne, unflappable, rugged, and a veteran of the early days of aviation, emerged from the hangar with a smile and his leather flying helmet already on, the chin buckles swaying slightly as he walked toward her. He pointed upward. “She’s ready if you’re ready.” He laughed, as if Elsie would have another answer.

She called Chim back, gave him a quick pet and a kiss, and followed Herne to the field where his biplane stood, ready for a jaunt down the runway, which was a short, clear path through a field of grass dotted with wildflowers. With the soles of her black leather spool-heeled oxfords on the wing, Elsie pulled herself up using the lift wires that crossed between the two wings and settled into the rear cockpit. They flew into the air within seconds, and Elsie breathed it in deeply and solidly. She smiled. She had an idea.

“Say, Hernie!” she shouted to him through the cockpit telephone when they had climbed to a distinguished altitude. “Loop her around the other way!”

The veteran flier knew that was a maneuver that meant bringing the plane to a loop with the wheels toward the inside, putting a terrific strain on the struts; the craft wasn’t built to fly that way. But after a glance at his and her safety belts, Herne shook off his caution and shoved the nose of the machine down and turned her over.

Elsie laughed with delight; nearly upside down, she already knew that she was the only woman who had looped with the wheels inside the circle.

“Attaboy, Hernie!” she shouted with a wide smile. “Attaboy!”

Herne laughed, too, then saw the wings fluttering under tremendous pressure like a flag in a windstorm. His smile quickly vanished; he tried to bring the plane back over.

“Turning over!” he shouted back to Elsie, but she did not hear him. The only sound was the howl as her safety belt ripped away from her shoulder and the screaming wind as it snatched her out of the plane. As she was pulled into the air, her hands clenched the bracing wires, clinging to them desperately. They were the only things keeping her from hurtling to the ground miles below.

Herne immediately turned around; he saw her twirling in the air like a stone tied at the end of a string. He lowered the nose, careful not to dive too fast. The wind pressure on her must be enormous, he thought. Good Christ, that girl is never going to make it to the ground. She’s not going to make it.

Elsie knew only that she needed to keep her grip strong and tight. She needed to hold that wire as fiercely as she could; she knew only not to let go. She was in a vacuum, the wind engulfing and beating against her at the same time.

Hold.

There was no other thought.

Hold.

Herne brought the plane down as gently as he could, the pressure of the wind easing a bit as they approached landing. Elsie swung her right leg into the cockpit and was able to pull herself back in, still holding on to the wire. The plane rolled to a stop and Herne reached back for her, scrambling out of his seat and helping her onto the wing.

“Let go,” he said, her hands still clenched around the wire. “Elsie, let go now.”

“Yes,” she agreed, her face red and chafed, but her eyes wide and bright. “Yes, I know, but I am not sure if I can.”

Herne lifted the fingers up one by one, uncurling them, releasing the lifeline of the wire, which he saw had cut through her gloves and straight to the bone.

She saw what he saw, and as he helped her to the hangar with only one of her oxfords missing, he patted her quickly on the shoulder and said, “I bet you’ll never ask me to do that again!”

Elsie looked at him, her hands held out, palms up and smeared with blood.

“I’ll loop her anytime,” she said, smiling. “Just get me a stronger safety belt.”

* * *

The third and favorite daughter of James Lyle Mackay—or, as of recently, Lord Inchcape, as he was pronounced by the king—Elsie Mackay reminded her father far too much of himself. At a glance, she was a lady, slight in stature, daughter of a peer, a privileged aristocrat wearing gowns of gold and beaded silk, a cohort of Princess Mary, the only daughter of George V. But under the surface of that thin veneer, Lord Inchcape had seen the will of his daughter evolve right before his eyes, her boldness take hold. She was not like her older sisters, Margaret and Janet, who knew and understood their duties. She was most unlike Effie, his youngest daughter, who was kind to the point of meekness and rarely put herself ahead of anyone or anything.

Elsie had failed at nothing. Whatever she set her sights to, she was almost always a quick, blooming success. He was always proud of her for that, but it was also what terrified him the most. W

hatever his daughter desired, wanted, pined for, all she had to do was take a step toward it. It was delivered.

While Elsie was bold, her choices were even bolder. He had learned that lesson in the hardest way. As the chairman to Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company and the director of the National Provincial Bank, he recognized a tremendous and dangerous facet of his daughter; she was unafraid, a trait he nearly despised himself for giving her.

From the broad window in his study at Seamore Place, he saw her silver Rolls flash by, the tires crunching on the pea gravel of the drive, Chim’s head out the window as the breeze blew his ears back. Oddly, she was steering the car with her palms, as her hands appeared to be half-gloved. He shook his head and laughed. She was always experimenting with some new fashion. He remembered when she sliced her hair from tresses into a bob; he never had the heart to tell her that from behind she resembled a boy. This one looked more senseless than the others. Half gloves!

It wasn’t until they had seated for dinner that he saw the trend he had been laughing at was actually bandages that rendered his daughter’s hands almost useless.

“Now, before you say anything, Father,” she said the moment she saw his mouth drop as Effie and Mother braced themselves for the scolding, “it’s not as bad as it seems. Just two cuts; they will heal quickly.”

“Exactly how bad are they?” he demanded. “Your hands are entirely bandaged!”

“Not all useless.” Elsie grinned slightly as she wiggled the tops of her fingers that were visible above the wrappings.

“Let me ask if this injury was a result of your reckless hobby. I warned you about propellers and hot parts of the engine,” he said sternly. “Airplanes! Ridiculous! This is complete insanity. I don’t know why . . . anyone—”

“You mean a woman, Father,” Elsie interrupted, mimicking his stern stare and furrowed brow.

Effie giggled as Lady Inchcape suddenly looked away and smiled.

“All of my daughters are capable of anything they set their mind to. But you have so much already on your schedule with the design of the new ship that learning to fly an airplane seems preposterous to me, and that is aside from the prevalent danger,” he insisted, then softened. “My darling girl, my thoughts are only for you.”

The women burst out laughing, and Inchcape grinned as he cut into his roast.

“It’s quite safe, I can assure you,” Elsie relayed. “As long as you have a reliable safety belt, it can be quite a delightful hobby.”

“At the very least, you’ll have Dr. Cunningham look at it,” he added after he had swallowed.

“I am a nurse, dear father,” she reminded him. “You do remember that.”

“Oh, indeed I do,” he volleyed. “And it is because of the result of your nursing that I am so concerned for you now. We nearly lost you once, Mousie Mine, with that marriage incident, and I am reluctant to lose you again. Your girlish charms have unbridled powers.”

Elsie smiled slightly as a response, but quickly withdrew it. She wasn’t hungry—the food on her plate actually repelled her—and her fingers were throbbing. After Herne had pried her sliced hands off the bracing wire, he wrapped one of them with her handkerchief and the other with her flying scarf, then drove her to Dr. Cunningham, who stitched ten loops in her right and twelve in her left, and gave her a small bottle of laudanum for the pain. Elsie would get the use of her hands back in several weeks, the doctor said, but until then, there was no flying. Herne looked on and agreed.

“I’m going upstairs,” Elsie said as she pushed back her chair. “I’m in need of some rest. Sophie had said she might stop by; if she does, send her up, will you?”

* * *

Upstairs in her room, Elsie took a sip of the laudanum and slid into her bed. The palms of her hands were beginning to bristle with sharp pain. It was nothing, she thought as she swallowed the bitter liquid, nothing compared to what she had seen during the war. This was nothing but a scrape. She laughed at herself.

Out of her bedroom window she could see the lights of Mayfair start to shimmer as London came to bright life at night. She had just missed the view as the sun finished settling below the horizon, nestling right behind the arches of Hyde Park, which Else’s bedroom window looked out over from the third floor.

She laid her head back on the pillow and closed her eyes. It was not lost on her how right her father was, and just how close she had come today to cutting her life short. She had fallen out of a plane a thousand feet in the air. She knew she should be terrified and unwilling to even look at another plane again, but she simply couldn’t locate the fright in herself.

The laudanum was beginning to seep in, softening everything. She thought about the flight at the moment right before she was ripped out of her seat. The thrill of the inside loop was so absorbing, she pictured it over and over again. Flying was an indescribable release for her, one she first discovered when she was stationed at Northolt, one of biggest aviation centers during the war. She understood the pilots she had seen taking off, suited up in their leather and gloves, confident and unyielding, and their passion for flying. She knew the damage these men would experience in a crash, if they survived at all. Horrible burns, broken limbs, shattered spines. And many of them healed, got stronger, and went right back into the cockpit. A cut on the hand was nothing next to what she had seen, wrapped, cleaned, and treated.

Despite the horror of the things she had witnessed, she missed her time at Northolt. When England declared war on Germany in 1914, she was in the thick of the cheering and determination, and also the center of the silent, underlying panic of families about to see off their sons and husbands, who would come home as different men with pieces inside them that didn’t fit together anymore—if they returned at all. She was twenty-one, and her accomplishments consisted of mentions in the gossip column in the Daily Express for what she wore to a dinner party or the hat she wore when presented at court.

Sophie Ries, her close friend since childhood, had joined the Voluntary Aid Detachment at the outbreak of the war as many girls of the upper classes had, training to be nurses to aid the national effort. Elsie galloped at the chance and proposed to her father that she must also do something. It wasn’t until Margaret and Janet, egged on by their younger sister, announced their plans to go join the VAD that he conceded.

With the urgency of war always present, the Mackay sisters learned first aid and how to give blanket baths, feed a soldier, and keep a ward clean. Far from any sort of silk gold net, Elsie found herself in a painfully starched blue uniform crowned with a large white overlay, like a nun’s habit, that she ripped off hastily at the end of every shift.

Although Janet and Margaret approached their roles with a brawny sense of duty, Elsie felt more at ease talking with each patient, attempting to puncture some of their loneliness with a few minutes of conversation. It was not an approach the professional nurses sanctioned, but filling the need for a soldier, blinded and burned by mustard gas, or shot through the jaw and unable to speak a word, to have a bedside companion did more for them than a swift cleaning of a bandage or the spooning of soup between grimaced lips.

After several months, Elsie was transferred to Northolt, a training squadron in West London, to be a courier and driver. Angry about being removed from nursing, she felt that her time with the wounded had been not only beneficial but necessary for her patients.

The base was not just a training squadron: It was a Royal Flying Corps aerodrome, newly built for the No. 4 Reserve Aeroplane Squadron. The cavernous hangars stretched in a single row to the horizon; the sound of whirring motors hummed steadily, like a beehive. Within several seconds a plane touched down and another took off. Another sputtered into the air and one landed in the dirt field with a hard bounce.

“Is it always like this, sir?” Elsie asked her commanding officer, her anger evaporating. “Or are they practicing for something?”

“Going to start flying sorties in defense of London against the Zeppeli

n air raids,” the officer said. “You got here just in time. Can you drive?”

“I can.” Elsie smiled. “Tight and fast.”

“What kind of car can you handle?” he asked.

“Bentley or a Rolls-Royce,” she said.

He laughed. “How about a Crossley?” he said.

“Still has a great kick to it, sir,” Elsie said, waving away the dust cloud the last landing plane had created.

* * *

As a driver to the higher-ranking officers and even some of the pilots, Elsie tore the stocky, curved convertible from hangar to base. The sight of her burning up Uxbridge Road, a major street in London, with a car full of brass hats was common. Driving was delightful, she found, but flying was the activity that Elsie really loved—taking off, landing, circling, the swooping as the pilots performed daredevil stunts during test flights. She tried to imagine what being in the air felt like, what the ground looked like from above, how brash the wind felt on the face, and what exhilaration it was to dip and dart among the clouds like a bird. After delivering several officers to headquarters, a ruddy-cheeked, handsome young pilot asked if he might catch a lift with her to the farthermost hangar.

“I’ll drive you around all week if you take me for a spin in one of those biplanes,” she countered with her brightest smile.

“Afraid of heights?” he asked wryly.

“Possibly not.” She shrugged.

“Won’t get mad if your hair gets mussed?”

Elsie laughed loudly. “Look at it,” she said. “I just had it bobbed. I drive a convertible all day and it hit an officer in the face. I believe he ate some of it.”

The pilot laughed and Elsie leaned over to open the passenger door.

“Tony Joynson-Wreford,” the pilot said, extending his hand after he got in.