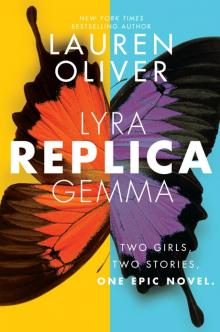

Replica

Lauren Oliver

CONTENTS

A Note from Lauren Oliver

Lyra Dedication

Author’s Note

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Praise

Gemma Author’s Note

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Praise

Back Ad

About the Author

Books by Lauren Oliver

Copyright

About the Publisher

A NOTE FROM LAUREN OLIVER

Dear Reader,

I’m thrilled to introduce you to the world of Lyra and Gemma and their intertwining stories. Replica is really two books in one and can be read in several different ways. Don’t be intimidated. The structure is designed to invite exploration and to promote unique reading experiences, in keeping with some of the book’s themes: fluid perception and unstable reality; the way our lives both touch other people’s and are changed by our contact with others; and the complex web of cause and effect in which we are all bound together. Both Lyra and Gemma must go on journeys in this book, and I hope that the reading experience will be, for you, a kind of journey.

Look for the cues at the end of each chapter to guide you. If you would like to read Lyra’s story or Gemma’s story in its entirety before switching perspectives, simply read as you normally would, swiping to continue at the end of each chapter. If, however, you want to read Lyra and Gemma’s stories in alternating chapters, the links at the end of each chapter will move you back and forth and allow you to pick up at any point from where you last left off, in either girl’s story.

However you choose to read, I hope you love reading Lyra and Gemma’s stories as much as I loved writing them.

Best regards,

Lauren Oliver

DEDICATION

To my sister, Lizzie

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Although in many cases you will find identical portions of dialogue occurring from both Gemma’s and Lyra’s perspectives in their respective narratives, you may also notice minor variations in tone and tempo. This was done deliberately to reflect their individual perspectives. Gemma and Lyra have unique conceptual frameworks that actively interact with and thus define their experiences, just as the act of observing a thing immediately alters the behavior of the thing itself.

The minor variations in the novel reflect the belief that there is no single objective experience of the world. No one sees or hears the same thing in exactly the same way, as anyone who has ever been in an argument with a loved one can attest. In that way we truly are inventors of our own experience. The truth, it turns out, looks a lot like making fiction.

ONE

ON VERY STILL NIGHTS SOMETIMES we can hear them chanting, calling for us to die. We can see them, too, or at least make out the halo of light cast up from the shores of Barrel Key, where they must be gathered, staring back across the black expanse of water toward the fence and the angular white face of the Haven Institute. From that distance it must look like a long green jaw set with miniature teeth.

Monsters, they call us. Demons.

Sometimes, on sleepless nights, we wonder if they’re right.

Lyra woke up in the middle of the night with the feeling that someone was sitting on her chest. Then she realized it was just the heat—swampy and thick, like the pressure of somebody’s hand. The power had gone down.

Something was wrong. People were shouting. Doors slammed. Footsteps echoed in the halls. Through the windows, she saw the zigzag pattern of flashlights cutting across the courtyard, illuminating silvery specks of rain and the stark-white statue of a man, reaching down toward the ground, as though to pluck something from the earth. The other replicas came awake simultaneously. The dorm was suddenly full of voices, thick with sleep. At night it was easier to speak. There were fewer nurses to shush them.

“What’s wrong?”

“What’s happened?”

“Be quiet.” That was Cassiopeia. “I’m listening.”

The door from the hall swung open, so hard it cracked against the wall. Lyra was dazzled by a sudden sweep of light.

“They all here?” It sounded like Dr. Coffee Breath.

“I think so.” Nurse Don’t-Even-Think-About-It’s voice was high and terrified. Her face was invisible behind the flashlight beam. Lyra could make out just the long hem of her nightgown and her bare feet.

“Well, count them.”

“We’re all here,” Cassiopeia responded. One of them gasped. But Cassiopeia was never afraid to speak up. “What’s going on?”

“It must be one of the males,” Dr. Coffee Breath said to Nurse Don’t-Even-Think-About-It, who was really named Maxine. “Who’s checking the males?”

“What’s wrong?” Cassiopeia repeated. Lyra found herself touching the windowsill, the pillow, the headboard of bed number 24. Her things. Her world.

At that moment, the answer came to them: voices, shrill, calling to one another. Code Black. Code Black. Code Black.

Almost at the same time, the backup generator kicked on. The lights came up, and with them, the alarms. Sirens wailed. Lights flashed in every room. Everyone squinted in the sudden brightness. Nurse Don’t-Even-Think-About-It stumbled backward, raising an arm as though to shield herself from view.

“Stay here,” Dr. Coffee Breath said. Lyra wasn’t sure whether he was speaking to Nurse Don’t-Even-Think-About-It or to the replicas. Either way, there wasn’t much choice. Dr. Coffee Breath had to let himself into the hall with a code. Nurse Don’t-Even-Think-About-It stayed for only a moment, shivering, her back to the door, as if she expected that at any second the girls might make a rush at her. Her flashlight, now subsumed by the overheads, cast a milk-white ring on the tile floor.

“Ungrateful,” she said, before she, too, let herself out. Even then they could see her through the windows overlooking the hall, moving back and forth, occasionally touching her cross.

“What’s Code Black?” Rose asked, hugging her knees to her chest. They’d run out of stars ever since Dr. O’Donnell, the only staff member Lyra had never nicknamed, had stopped giving them lessons. Instead the replicas selected names for themselves from the collection of words they knew, words that struck them as pretty or interesting. There was Rose, Palmolive, and Private. Lilac Springs and Tide. There was even a Fork.

As usual, only Cassiopeia—number 6, one of the oldest replicas besides Lyra—knew.

“Code Black means security’s down,” she said. “Code Black means someone’s escaped.”

Turn the page to continue reading Lyra’s story. Click here to read Chapter 1 of Gemma’s story.

TWO

H-U-M-A-N. THE FIRST WORD WAS hu-man.

There were two kinds of humans: natural-born humans, people, women and men, girls and boys, like the doctors and staff, the researchers, the guards, and the Suits who came sometimes to survey the island and its inhabitants.

Then there were human models, males and females, made in the laboratory and transferred to the surrogate birthers, who lived in the barracks and never spoke English. The clones, people occasionally still c

alled them, though Lyra knew this was a bad word, a hurtful word, even though she didn’t know why. At Haven they were called replicas.

The second word was M-O-D-E-L. She spelled it, breathing the sounds lightly between her teeth, the way that Dr. O’Donnell had taught her. Then: the number 24. So the report was about her.

“How are you feeling today?” Nurse Swineherd asked. Lyra had named her only last month. She didn’t know what a swineherd was but had heard Nurse Rachel say, Some days I’d rather be a swineherd, and had liked the sound of it. “Lots of excitement last night, huh?” As always, she didn’t wait for a response, and instead forced Lyra down onto the examination table, so she no longer had a view of the file.

Lyra felt a quick flash of anger, like a temporary burst in her brain. It wasn’t that she was curious about the report. She had no desire in particular to know about herself, to find out why she was sick and whether she could be cured. She understood, in general terms, from things insinuated or overheard, that there were still glitches in the process. The replicas were born genetically identical to the source material but soon presented with various medical problems, organs that didn’t function properly, blood cells that didn’t regenerate, lungs that collapsed. As they got older, they lost their balance, forgot words and place names, became easily confused, and cried more. Or they simply failed to thrive in the first place. They stayed skinny and stunted. They smashed their heads on the floor, and when the Suits came, screamed to be picked up. (In the past few years God had mandated that the newest generational crops be picked up, bounced, or engaged in play for at least two hours every day. Research suggested that human contact would keep them healthier for longer. Lyra and the other older replicas took turns with them, tickling their fat little feet, trying to make them smile.)

Lyra had fallen in love with reading during the brief, ecstatic period of time when Dr. O’Donnell had been at Haven, which she now thought of as the best months of her life. When Lyra read, it was as if a series of small windows opened in the back of her mind, flooding her with light and fresh air and visions of other places, other lives, other, period. The only books at Haven were books about science and the body, and these were difficult and full of words she couldn’t sound out. But she read charts when they were left unattended on countertops. She read the magazines the nurses left behind in their break room.

Nurse Swineherd kept talking while she took Lyra’s blood pressure with Squeezeme and stuck Thermoscan under her tongue. Lyra liked Squeezeme and Thermoscan. She liked the way Squeezeme tightened around her upper arm, like a hand holding on to lead her somewhere. She liked Thermoscan’s reassuring beeps, and afterward when Nurse Swineherd said, “Perfectly normal.”

She added, “Don’t know what it was thinking, running that way. Breathe deeply, okay? Good. Now exhale. Good. It’ll drown before it gets past the breaks. Did you hear the surf last night? Like thunder! I’m surprised the body hasn’t turned up already, actually.”

Lyra knew she wasn’t expected to reply. The one time she had, in response to Nurse Swineherd’s cheerful question, “How are we today?” Nurse Swineherd had startled, dropping one of the syringes—Lyra hated the syringes, refused to name them—and had to start over. But she wondered what it would be like to come across the dead body on the beach. She wasn’t afraid of dead bodies. She had seen hundreds of replicas get sick and die. All the Yellows had died, none of them older than twelve months. A fluke, the doctors said: a fever. Lyra had seen the bodies wrapped and prepared for shipping.

A Purple from the seventh crop, number 333, had simply stopped eating. By the time they put her on a tube, it was too late. Number 501 swallowed twenty-four small white Sleepers after Nurse Em, who used to help shave her head and was always gentlest with the razor, went away. Number 421 had gone suddenly, in her sleep. It was Lyra who’d touched her arm to wake her and known, from the strange plastic coldness of her body, that she was dead. Strange that in an instant all the life just evaporated, went away, leaving only the skin and bones, a pile of flesh.

But that’s what they were: bodies. Human and yet not people. She hadn’t so far been able to figure out why. She looked, she thought, like a normal person. So did the other female replicas. They’d been made from normal people, and even birthed from them.

But the making of them marked them. That’s what everybody said. Except for Dr. O’Donnell.

She wouldn’t mind seeing a male up close—the male and female replicas were kept separate, even the dead ones that went off the island in tarps. She was curious about the males, had studied the anatomical charts in the medical textbooks she couldn’t otherwise read. She had looked especially closely at diagrams of the female and male reproductive organs, which seemed, she thought, to mark the primary difference between them, but she couldn’t imagine what a male’s would look like in real life. The only men she saw were doctors, nurses, security, and other members of the staff.

“All right. Almost done. Come here and stand on the scale now, okay?”

Lyra stood up, hoping to catch a glimpse once again of the chart, and its beautiful, symmetrical lettering, which marched like soldiers across the page. But Nurse Swineherd had snatched the clipboard and was writing in Lyra’s newest results. Without releasing her grip on the clipboard, she adjusted the scale expertly with one hand, waiting until it balanced correctly.

“Hmmm.” She frowned, so that the lines between her eyebrows deepened and converged. Once, when Lyra was really little, she had announced that she had found out the difference between people and replicas: people were old, replicas were young. The nurse who was bathing her at the time, a nurse who hadn’t stayed long, and whose name Lyra could no longer remember, had burst out laughing. The story had quickly made the rounds among the nurses and doctors.

“You’ve lost weight,” Nurse Swineherd said, still frowning. “How’s your appetite?”

Several seconds went by before Lyra realized this was a question she was meant to answer. “Fine.”

“No nausea? Cramping? Vomiting?”

Lyra shook her head.

“Vision problems? Confusion?”

Lyra shook her head because she wasn’t very practiced at lying. Two weeks ago she’d vomited so intensely her ribs had ached the following day. Yesterday she’d thrown up in a pillowcase, hoping it would help muffle the sound. Fortunately she’d been able to sneak it in with the rest of the trash, which went off on boats on Sundays, to be burned or dumped into the sea or otherwise disposed of. Given the storm, and the security breach, and the now-probably-dead male, she was confident no one would notice the missing pillowcase.

But the worst thing was that she had gotten lost yesterday, on her way back to the dorms. It didn’t make any sense. She knew every inch of D-Wing, from Natal Intensive to Neural Observation, to the cavernous dorms that housed one hundred female replicas each, to the bathrooms with dozens of showerheads tacked to a wall, a trench-like sink, and ten toilets. But she must have turned right instead of left coming out of the bathroom and had somehow ended up at the locked door that led into C-Wing, blinking confusedly, until a guard had called out to her and startled her into awareness.

But she wouldn’t say so. She couldn’t go to the Box. That’s what everyone called G-Wing. The Box, or the Funeral Home, because half the replicas that went in never came out.

“All right, off you go,” Nurse Swineherd said. “You let me know if you start feeling sick, okay?”

This time, she knew she wasn’t expected to answer. She wouldn’t have to tell anyone she kept throwing up. That was what the Glass Eyes mounted in the ceiling were for. (She wasn’t sure whether she liked the Glass Eyes or not. Sometimes she did, when the chanting from Barrel Key was especially loud and she thought the cameras were keeping her safe. Sometimes, when she wanted to hide that she felt sick, she hated them, those lashless lenses recording her every move. That was the problem: she never knew which side the Glass Eyes were on.)

But she nodded anyway. Lyra had

a plan, and the plan required her to be good, at least for a little while.

Turn the page to continue reading Lyra’s story. Click here to read Chapter 2 of Gemma’s story.

THREE

THREE DAYS LATER, THE BODY of male number 72 had still not washed up on the beach, as everyone had predicted. At breakfast the day after trash day, Lyra heard the nurses discussing it. Don’t-Even-Think-About-It shook her head and said she was sure the gators had gotten him. If he did make it onto the mainland, she said, he’d likely be shot on sight—nothing but crazies and criminals living out here for miles. And now those men are coming, she added, shaking her head. That was what all the nurses called the Suits: those men.

Lyra had seen their boat in the distance on her way into breakfast: a sleek, motorized schooner, so unlike the battered barge that carted supplies in and trash out and looked as if it was one teaspoon of water away from sinking. She didn’t know exactly what the Suits did, who they were, or why they visited Haven. Over the years she’d heard several references to the military, although they didn’t look like soldiers, at least not the ones she occasionally saw on the nurses’ TV. These men didn’t wear matching outfits, or pants covered in camouflage. They didn’t carry weapons, like the guards did.

When she was younger, the Suits had made Lyra nervous, particularly when all the replicas were forced to line up in front of them to be inspected. The Suits had opened her mouth to look at her teeth. They had asked her to smile or turn around or clap on command, to show she wasn’t an idiot, wasn’t failing to thrive, to wiggle her fingers or move her eyes from left to right.

The inspections had stopped a long time ago, however. Now the Suits came, walked through all the wings, from Admin to the Box, spoke to God, and then returned to the mainland on their boat, and Lyra found that she’d grown less and less interested in them. They belonged to another world. They might as well have been flies touching down, only to take flight again. They didn’t matter to her, not like Thermoscan did, not like her little bed and her windowsill and the meaning embedded deep in a hieroglyph of words.