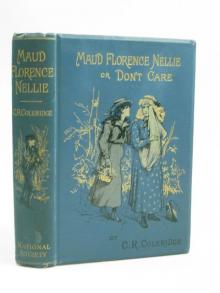

Maud Florence Nellie; or, Don't care!

L. T. Meade

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

Maud Florence NellieDon't careBy C.R. ColeridgeIllustrations by C.J. StanilandPublished by National Society's Depository, London.

Maud Florence Nellie, by C.R. Coleridge.

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________MAUD FLORENCE NELLIE, BY C.R. COLERIDGE.

CHAPTER ONE.

MAUD FLORENCE NELLIE.

Maud Florence Nellie Whittaker was standing before her littlelooking-glass, getting ready for her afternoon Sunday school. She was afine tall girl of fifteen, rather stoutly made, with quantities of lightbrown hair, which fell on her shoulders and surrounded her plump rosyface with a perfect halo of fringe and friz. She had hazel eyes, whichwere rather bold and rather stupid, a cocked up nose, and full red lips,which could look sulky; but which were now curved in smilingsatisfaction at the new summer hat, all creamy lace and ribbons, whichshe was fixing at exactly the right angle above her curly hair. She hadon a very fashionable cream-coloured costume to match the hat, andaltogether she was justified in considering herself as one of the bestdressed girls in her class, and one whose good looks were not at alllikely to pass unnoticed as she took her way along the sunshiny roadthat led into the large country town of Rapley. Her fine frock, her biggirlish form, and her abundant hair seemed to fill up the little bedroomin which she stood; which had a sloping roof and small latticed windows,though it was comfortably furnished and had no more appearance ofpoverty than its inhabitant. Florrie Whittaker lived in the lodge atthe gate of the great suburban cemetery, which had replaced all thedisused churchyards of Rapley. Her father was the gatekeeper andcaretaker, and as the cemetery was a very large one the post wasimportant and the salary good. Florrie and her brothers and sisters hadrun up and down the rows of tomb-stones and played in the unoccupiedspaces for as long as most of them could recollect. They saw manyfunerals everyday, and heard the murmur of the funeral service and thetoll of the funeral bell whenever they went out, but it never occurredto them to think that tomb-stones were dismal or funerals impressive;they looked with cheerful living eyes at their natural surroundings, andnever thought a bit more of the end of their own lives because they soconstantly saw the end of other people's. Florrie finished herself upwith a red rosebud, found her hymn-book and a pair of new kid gloves,and then with a bounce and a clatter ran down the narrow stairs into thefamily sitting-room below; where the din of voices betokened thefather's absence, and the bustle attendant on starting for school on thepart of a boy and two girls younger than herself.

"You'll all be late, children, and get bad marks from your teachers,"cried Florence, in a loud gay voice.

"And what'll you be?" was the not unnatural retort of the next sister,Sybil.

"It ain't the same thing in _my_ class," returned Florrie. "Teacherknows that girls of my age can't be punctual like little ones. They'veto clear away, and mind the children, and all sorts of things to do."

"And what have you been clearing away?"

"And who have you been minding of?"

"And what have _you_ had to do but put your fine hat on?" rose in achorus from the indignant children; while another voice put in--

"When _I_ went to school the elders came punctual for the sake of anexample."

"Oh my! Aunt Lizzie, I didn't see you," said Florrie. "How d'ye do?There's plenty of examples nowadays if one wanted them, which I don't."

"I'm sure, Aunt Lizzie," put in the eldest sister, a tall young woman ofnineteen or so, "there isn't harder work in the world than in trying toset an example to _Florrie_."

"You don't set a nice one," said Florrie.

"It would be a deal better for you, Florence," said her aunt, "if youdid take example by some one. You're getting a big girl, and that hatand frock are a deal too smart to run about the roads in. When I was agirl, I had a nice brown mushroom hat and a neat black silk jacket, andpleased enough I was with them as a new thing."

"And did _your_ aunts wear mushroom hats and black silk jackets?" saidFlorrie.

"My aunts? no, indeed! Whatever are you thinking of, Florence? Myaunts were most respectable women, and wore bonnets, when bonnets _was_bonnets. Hats, indeed!"

"Your hat was in the fashion then, and mine's in the fashion now," saidFlorence saucily; but Aunt Lizzie, refusing to perceive that her niecehad made a point, continued, "Aunt Eliza Brown was married to a man inthe grocery way, and Aunt Warren, as you very well know, was housekeeperto Mr Cunningham at Ashcroft Hall, and married the head keeper, whichher son has the situation to this day."

"I do tell Florrie," said the elder sister again, "that she'd look adeal more like a real lady if she dressed a bit quieter than she does."

"I don't want to look like a lady. I want to have my fun," saidFlorrie. "Come on, Ethel, if you're coming; I want to catch up withCarrie and Ada. Good-bye, aunt; I like lessons best in school."

And off dashed Florrie through the summer sunshine, between the avenueof monuments, her hair flying, her skirts swinging, and her loud livelyvoice sounding behind and before her as she scurried along.

"Well!" said Aunt Lizzie, "she be a one, surely. That girl wants atight hand over her, Martha Jane, if ever a girl die yet."

Aunt Lizzie--otherwise Mrs Stroud--was an excellent person, and had"kept her brother's family together," as she expressed it, ever sincetheir mother's death; but she was not invariably pleasant, and hereldest niece disliked being called Martha Jane much more than Florencedisliked being scolded for her finery. When all the younger ones hadsuch beautiful names--Maud Florence Nellie, Ethel Rosamond, and SybilEva Constance--it was hard upon her that she had been born before hermother's love of reading, and perhaps her undeveloped love of thebeautiful things of life, had overcome the family traditions. "Martha"was bad enough, and she did not know that the children's use of "Matty"was a fashionable variation of it. But "Martha Jane!"

She was not, however, saucy like Florence, so she only sighed a littleand said:

"I do my best, indeed, aunt; but won't you lay off your mantle and sitdown comfortably? Father won't be in yet. He likes to be round, whenso many friends come to visit the graves and put flowers, in case ofmischief, and the children won't be back for near two hours."

Mrs Stroud was a stout comfortable woman, not very unlike what herniece Florence might be after five and thirty more years in a workadayworld had marked and subdued her beaming countenance. She was glad tosit down after the hot walk, take off her cloth mantle, which, though aneminently dignified and respectable garment, was rather a heavy one fora June day, and fan herself with her pocket-handkerchief, while sheinquired into the well-being of her nieces and nephews. Martha Jane wasof a different type--dark and slim, with pretty, rather dreamy greyeyes, and a pale refined face. She was a good girl, and tried to do herduty by her young brothers and sisters; but she had not very stronghealth or spirits, and in many ways she wished that her life wasdifferent from what fate had made it.

"That there Florrie," said Mrs Stroud, "ain't the sort of girl to beallowed to _stravage_ about the roads by herself for two hours."

"Why, aunt, she must go to her Bible class," said Martha meekly.

"Well," said Mrs Stroud, "there's girls that aren't calculated forBible classes, in my opinion. Does she come in punctual from her workon weekdays?"

"Oh, yes, aunt, and it's supposed that George meets her. Not that healways does; but she has to look out for him. And Mrs Lee keeps hervery strict at the shop. She don't have her hair flying about onweekdays, nor dress fine, and she's a good girl for her work and verycivil, Mrs Lee s

ays. You wouldn't know Florrie when she's behaving."

"Pity she don't behave always then," said Mrs Stroud.

"That's just the thing," said Martha, "I tell her, aunt, constant. Itell her to read the tales out of the library, and see what the youngladies are like that are written about in them. And she says a tale maybe a tale, but she ain't in a book, and she don't want to be. Florrie'salways got an answer ready."

"Well, Martha Jane, I don't hold much with wasting time over tales andnovels myself. You read a deal too many, and where's the good?"

"I