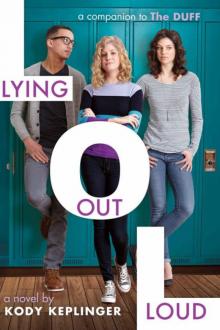

Lying Out Loud

Kody Keplinger

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Copyright

I, Sonny Elizabeth Ardmore, do hereby confess that I am an excellent liar.

It was never something I aspired to be, but rather a talent that I couldn’t avoid. It started with lies about my homework — I could actually convince teachers that my dog ate it, with fake tears and everything if needed — and then I told lies about my family — my father was an international businessman, not a deadbeat thief who’d been tossed in jail when I was seven — and, eventually, I was lying about everything else, too.

But as excellent a liar as I may be, lying hasn’t led me to much excellence lately. So let the record show that this time I am telling the truth. All of it. The whole shebang. Even if it kills me.

* * *

I tell the most lies on bad days, and the Friday my cell phone — one of those old, clunky, pay-as-you-go bricks that only played polyphonic ringtones — decided to stop working after six long years of use, was a particularly bad day.

It had flatlined sometime in the night, a peaceful, quiet sort of death, and left me without my usual five a.m. alarm. Instead, I awoke when Amy’s phone (the newest, most expensive model of smartphone, naturally) began blaring an all-too-realistic fire truck–style siren.

I bolted upright, my heart jackhammering, while next to me, on her side of the bed, my best friend snoozed on.

“Amy.” I shoved her arm. “Amy, shut that thing off.”

She groaned and rolled over. The siren kept wailing as she fumbled with the phone. Finally, it went silent.

“Why in God’s name would you want to wake up to that sound?” I asked her as she stretched her long, thin arms over her head.

“It’s the only alarm loud enough to wake me up.”

“And it barely accomplishes that.”

It wasn’t until then that I realized what Amy’s horrible wake-up call meant. I was supposed to be up before her. I was supposed to get ready and sneak out of her house before her parents woke up at six. But my phone wasn’t working and it was six-fifteen and I, to put it bluntly, was fucking screwed.

“Why don’t you just tell my parents you fell asleep here last night?” Amy asked as I scrambled around the room, dragging out the duffel bag of wrinkled clothes I kept hidden under her bed. “They won’t care.”

“Because then they’ll want to go reassuring my mom about where I was,” I said, pulling a green T-shirt on over my incredibly impressive bedhead. “And that’ll open up a whole new set of questions, and just no.”

“I still don’t see why you can’t just tell them she kicked you out.” Amy stood up and started combing her dark curls, which, despite all the laws of physics, still looked perfect after a night’s sleep. Amy was one of those rare people who looked gorgeous first thing in the morning. It brought a whole new meaning to “beauty rest.” I would have hated her for it if I didn’t love her so much.

“It’s just too complicated, okay?”

I took the comb from her and began to work out the knots in my hair. That was the only thing Amy and I had in common — we both had insanely curly hair. Like corkscrew curls. The kind that everyone thinks they want but, in reality, you can’t do a damn thing with. But where Amy’s were long, dark brown, and perfect, mine were shoulder length, blond, and slowly destroying my sanity. It took forever to pick out the tangles each morning, and today, I didn’t have forever.

“Well, I hope you and your mom get it worked out soon,” she said, “because I love having you stay here, but this is getting a little too complicated.”

“You’re telling me.” She wasn’t the one who was about to make a two-story drop out of a window.

In the hall, I could hear Mr. Rush moving around, getting ready for work. Now, with my teeth unbrushed and without a speck of deodorant to cover up my glorious natural odor, was the time to make my escape.

I ran over to Amy’s window and shoved it open. “If I die doing this, please deliver a somewhat humorous but overall heartbreaking eulogy at my funeral, okay?”

“Sonny!” Amy grabbed my arm and dragged me away from the window. “No way. You’re not doing that.”

“Why not?”

“For starters, it’s not safe,” she said. When she realized that wasn’t enough to deter me, she added, “And also you’d be dropping right past the kitchen window. If Mom’s down there eating breakfast and sees a girl falling from the sky …”

“Good point. Damn it. What do I do?”

“Just wait until everyone leaves,” she said. “You can sneak out and lock the door with the spare key. It’s under the —”

“Flowerpot next to the door. Yeah. I know.”

And while this was a more practical plan, to be sure, it wasn’t the most suited for punctuality. Amy’s parents didn’t leave until seven-thirty, only fifteen minutes before I had to be at school. The minute the front door slammed, I scrambled down the hall and into the bathroom to finish my necessary hygiene rituals before bolting downstairs and out the door myself.

I locked up, then cut across their backyard and down Milton Street to the Grayson’s Groceries parking lot, where I had left my car the night before.

“Hello, Gert,” I said, tapping the hood of the old silver station wagon. She was one ugly beast of a car. But she was mine. I climbed into the front seat. “Hope you slept well, but I’m in a hurry, so please don’t be in a shitty mood today.”

I turned the key in the ignition. It revved, but the engine wouldn’t turn over. I groaned.

“Not today, Gert. Have some mercy.”

I tried again and, as if she’d heard me, Gert’s motor finally started to hum. And, just like that, we were off.

The bell had already rung by the time I pulled into the senior parking lot, which meant the main door had locked and Mrs. Garrison, the perpetually grumpy front desk lady, had to buzz me in.

“Sonya,” she said, greeting me when I got to the main office.

I cringed. I hated — hated — my full first name.

“You’re late,” she announced, as if I somehow wasn’t aware.

“I know. I’m sorry, I just …”

Showtime.

My lip started to quiver and, on cue, my eyes began to well up with tears. I looked down at my shoes and took a dramatic, raspy breath.

“My hamster, Lancelot, died this morning. I woke up and he was just … in his wheel … lying so still….” I covered my face with my hands and began to sob. “I’m sorry. You probably think it’s stupid, but I loved him so much.”

“Oh, sweetheart.”

“I know it’s not an excuse, but … I just … I’m sorry, Lancelot.”

I was worried I might be playing it up too much, but then she shoved a tissue into my hand and patted my arm sympathetically.

“Let it out,” she said. “I know it can be hard. When I lost Whiskers last year … Listen, I’ll write you a note for first block. I’ll say you had a family emergency. Don’t worry about it. I’ll make sure this is excused.”

“Thank you,” I sniffed

.

The tears had dried up by the time I reached my AP European history class. Mr. Buckley was in the middle of his lecture when I slipped into the room. Unfortunately, he never missed anything, so there was no chance of me sneaking back to my chair without him noticing.

“Ms. Ardmore,” he said. “You finally decided to join us.”

“Sorry to interrupt,” I said. “I have a note.”

I handed him the slip of paper I’d been given at the front desk. He read it quickly and nodded. “Fine. Take your seat. I suggest you borrow notes on the first part of the lecture from one of your classmates.”

“That’s it?” Ryder Cross asked as I slid into the seat behind his. “She comes in half an hour late and there are no consequences?”

“She has a note from the office, Mr. Cross,” Mr. Buckley said. “What consequences would you suggest?”

“I don’t know,” Ryder admitted. “But she disrupted the class by coming in late, and it’s not as if this is the first time. Back at my school in DC, the teachers were much more strict. Excuses were rarely accepted. And the students cared much more about their education, too. Here, it seems like just about anything can get excused.”

I rolled my eyes so hard it hurt. “Then go back,” I suggested. “Don’t worry about us simple folk here in Hamilton. We’ll make do without you. I assure you, you won’t even be missed.”

There was an appreciative murmur from the rest of the class. Even Mr. Buckley gave the tiniest of nods.

Ryder turned in his seat so that he could look me in the eye. The sad thing was, if he hadn’t been such a tool, he probably would have been popular around here. He had smooth brown skin and shockingly bright green eyes. His black hair was kept short and neat, but he was always dressed as if he was on his way to a concert for a band no one had ever heard of. Slightly disheveled, but in a very deliberate way. His clothes, though, always looked like they’d been tailored to fit his lean, muscular frame. On occasion I’d even seen him wear thick-rimmed glasses that I knew he didn’t need.

In other words, he was hot, but in an annoying, hipstery sort of way.

Since he’d arrived at Hamilton High at the beginning of the semester, he’d done nothing but dis everything about the school and its student body. The lunches at his school in DC were so much better, the kids at his school in DC walked faster in the hallways, the teachers at his school in DC were more qualified, the football team at his school in DC won more games, et cetera, et cetera.

Now, I wasn’t exactly bursting with school spirit, but even I couldn’t stand his attitude. Which became even more repulsive when he started posting snarky Facebook statuses about how lame our small town was. You’d think our lack of five-star fine dining was putting him in physical agony.

The long and short of it was, Ryder came from money. Political money. His father was a congressman from Maryland — a fact he never failed to share at any opportunity — and in his not-so-humble opinion, Hamilton and everyone who lived here sucked.

Everyone, that is, except Amy. Because Ryder had developed a disgustingly obvious and totally unrequited crush. I couldn’t fault him for that, though. Amy was gorgeous and rich, just like him. Amy, however, was the kind of girl who gave personalized Christmas cards to all of the lunch ladies, and he was a dick.

He was still staring at me, and I suddenly became all too aware of the jeans I’d been wearing for almost a week without washing them and the torn hem on the sleeve of my T-shirt. I straightened up and stared him down, daring him to compare me to the girls at his school in DC, but before he could say anything, Mr. Buckley cleared his throat.

“Okay, class. Enough’s enough. History is long, but we only have a year to get through this material. Now, let’s get back to the Great Schism, which, I know, sounds vaguely like toilet humor, but we’re going to press on, regardless.”

Ryder turned back around in his seat, and I went about my business taking notes on that unfortunately named moment in history.

Things were looking up until third block, when I realized I’d left my chemistry book at Amy’s. I had to convince Mrs. Taylor, who was a total hard-ass and known to give detention for lesser things, that I’d been tutoring at the local children’s hospital in Oak Hill and had accidentally left it with one of the kids.

“I’ll get it back from her tomorrow,” I said. “I’m going to see her before she starts her next round of chemo. I promise to get it back then.”

And she bought it. Hook, line, and sinker.

I was aware of my status as a terrible person. But I liked to think of my lying abilities as gifts. And why else would I have them if not to be used? Especially on days like this, where everything just seemed to be going wrong.

I didn’t have enough money in my wallet for lunch, so rather than admitting that things were shitty at home and I was broke, I told the much-too-soft-hearted cashier that I’d given my last dollar to the homeless man who occupied the corner a few blocks from school.

She covered it for me.

Then the strap on my crappy two-dollar flip-flop broke, a volleyball slammed right into my face in gym class, and, to top it off, I started my period.

Amy would call it karma. She’d say this was the universe’s punishment for all the lies. But, the truth was, the lying helped. When everything felt out of control, it put me back in control.

I was sure the day couldn’t get worse, which was, perhaps, my fatal flaw. When you let yourself think that things can’t get worse, they inevitably will.

“So I’ll see you tonight?” Amy asked as we headed out into the senior parking lot.

“Yep. I can’t text you, though, so you’ll have to watch for me. I’ll be outside around the usual time.”

“Okay.” She gave me a quick hug. “Have fun at work.”

I waved as she hurried off to her Lexus. I tried to tell myself I wasn’t horribly jealous of her and her rich parents and her fancy car. I had Gert, after all. Who wouldn’t want Gert?

I might have been good at lying, but even I didn’t buy that one for a minute.

I climbed into the car and tossed my backpack into the passenger’s seat. “All right, Gert,” I said, sticking the key in the ignition. “Time for work.”

But while I was a reliable employee (most of the time), Gert had decided she wasn’t in the mood today. The engine revved and revved, but nothing happened. The battery was dead, and I had to be at the movie theater for my shift in twenty minutes.

I grabbed my cell, planning to call Amy to ask for a ride, only to then remember that my ancient phone had recently breathed its last breath. I hopped out of the car, hoping to flag her down before she left the parking lot, but I was too late. I could already see the Lexus speeding off into the distance.

There was no way around it. I was stuck. I’d have to find someone to jump-start my car, and who knew how long that would take.

And just then, because it’s possible that all Amy’s theories about the universe’s revenge were true, the sky opened up and it began pouring rain. Leaving me with only one thing to say:

“Motherfucker.”

The senior parking lot was already close to empty when the rain started. I sat inside Gert, watching the exit and hoping someone would come out soon. Unfortunately, the first person to appear, my would-be savior, was a tall boy in the T-shirt of an obscure band, a distressed but still clearly expensive hoodie, and two-hundred-dollar jeans.

“You’ve got to be kidding me,” I said as I reached for the door handle. I wanted to just wait for the next person to come out, but who knew how long that would be. Chances were, the rest of these cars belonged to the overachieving types who stayed after school for chess club and student government. Those nerds and their resume-building activities were no good to me right now. So Ryder Cross was my only choice.

I hopped out of the car, holding my history textbook over my head to protect my curls from the downpour of doom.

“Ryder!” I shouted. He was already halfway across

the parking lot. “Hey, Ryder!”

He stopped and turned to look at me. He didn’t have an umbrella, and the rain was making his clothes cling to him. The view wasn’t half bad. Unfortunately, however, my next question would require him to speak.

“My car’s dead,” I said. “Do you have jumper cables or something?”

He started walking in my direction, but he was shaking his head. “I don’t.”

I sighed. “Of course not. Let me guess, the cars in DC don’t die? Or need repairs?”

“Can’t you call someone?”

“My phone doesn’t work.”

“Seems like everything around you is faulty.”

“Well, not everyone has politician parents to pay for our things. Some of us actually have to work for what we own. Your concern is appreciated, though.”

He rolled his eyes. “If you’re going to be like that, then forget it. I was going to let you use my phone.”

“Really?”

“Yeah. I’m not an asshole.”

“Debatable.”

“You’d be calling Amy, right?”

And there it was. The ulterior motive I’d been expecting. He was right, though. Who else would I call? I knew she wouldn’t have jumper cables, but she’d at least be able to give me a ride to the theater.

We climbed into Gert, both of us soaked. The carpeted seats would be brilliantly moldy the next day — something to look forward to. He handed me his phone, the same model as Amy’s, and I quickly dialed her number. It was the only one I had memorized.

“Hello?”

“Hey, Amy.”

“Sonny? Where are you calling from? I don’t recognize the number.”

“Our favorite human being was kind enough to bestow the honor of telephone usage on me.”

Silence.

“I’m borrowing Ryder’s phone.”

“Oh.”

I didn’t have to see her face to know her tiny button nose had wrinkled.

“My car’s dead and my phone is broken. And my shift is in … oh, seven minutes. Please help.”

“On my way.”

I returned the phone to Ryder. “She’s coming back to get me. So you can go now.” And then, with every ounce of willpower I had, I forced myself to add, “And thanks. For the phone.”