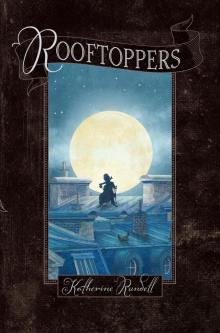

Rooftoppers

Katherine Rundell

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

About Katherine Rundell

To my brother, with love

1

ON THE MORNING of its First Birthday, a baby was found floating in a cello case in the middle of the English Channel.

It was the only living thing for miles. Just the baby, and some dining room chairs, and the tip of a ship disappearing into the ocean. There had been music in the dining hall, and it was music so loud and so good that nobody had noticed the water flooding in over the carpet. The violins went on sawing for some time after the screaming had begun. Sometimes the shriek of a passenger would duet with a high C.

The baby was found wrapped for warmth in the musical score of a Beethoven symphony. It had drifted almost a mile from the ship, and was the last to be rescued. The man who lifted it into the rescue boat was a fellow passenger, and a scholar. It is a scholar’s job to notice things. He noticed that it was a girl, with hair the color of lightning, and the smile of a shy person.

Think of nighttime with a speaking voice. Or think how moonlight might talk, or think of ink, if ink had vocal cords. Give those things a narrow aristocratic face with hooked eyebrows, and long arms and legs, and that is what the baby saw as she was lifted out of her cello case and up into safety. His name was Charles Maxim, and he determined, as he held her in his large hands—at arm’s length, as he would a leaky flowerpot—that he would keep her.

The baby was almost certainly one year old. They knew this because of the red rosette pinned to her front, which read, 1!

“Or rather,” said Charles Maxim, “the child is either one year old or she has come first in a competition. I believe babies are rarely keen participants in competitive sport. Shall we therefore assume it is the former?” The girl held on to his earlobe with a grubby finger and thumb. “Happy birthday, my child,” he said.

Charles did not only give the baby a birthday. He also gave her a name. He chose Sophie, on that first day, on the grounds that nobody could possibly object to it. “Your day has been dramatic and extraordinary enough, child,” he said. “It might be best to have the most ordinary name available. You can be Mary, or Betty, or Sophie. Or, at a stretch, Mildred. Your choice.” Sophie had smiled when he’d said “Sophie,” so Sophie it was. Then he fetched his coat, and folded her up in it, and took her home in a carriage. It rained a little, but it did not worry either of them. Charles did not generally notice the weather, and Sophie had already survived a lot of water that day.

Charles had never really known a child before. He told Sophie as much on the way home: “I do, I’m afraid, understand books far more readily than I understand people. Books are so easy to get along with.” The carriage ride took four hours; Charles held Sophie on the very edge of his knee and told her about himself, as though she were an acquaintance at a tea party. He was thirty-six years old, and six foot three. He spoke English to people and French to cats, and Latin to the birds. He had once nearly killed himself trying to read and ride a horse at the same time. “But I will be more careful,” he said, “now that there is you, little cello child.” Charles’s home was beautiful, but it was not safe; it was all staircases and slippery floorboards and sharp corners. “I’ll buy some smaller chairs,” he said. “And we’ll have thick red carpets! Although—how does one go about acquiring carpets? I don’t suppose you know, Sophie?”

Unsurprisingly, Sophie did not answer. She was too young to talk, and she was asleep.

She woke when they drew up in a street smelling of trees and horse dung. Sophie loved the house at first sight. The bricks were painted the brightest white in London, and shone even in the dark. The basement was used to store the overflow of books and paintings and several brands of spiders, and the roof belonged to the birds. Charles lived in the space in between.

At home, after a hot bath in front of the stove, Sophie looked very white and fragile. Charles had not known that a baby was so terrifyingly tiny a thing. She felt too small in his arms. He was almost relieved when there was a knock at the door; he laid Sophie down carefully on a chair, with a Shakespearean play as a booster seat, and went down the stairs two at a time.

When he returned, he was accompanied by a large gray-haired woman; Hamlet was slightly damp, and Sophie was looking embarrassed. Charles scooped her up and set her down—hesitating first over an umbrella stand in a corner, and then over the top of the stove—inside the sink. He smiled, and his eyebrows and eyes smiled too. “Please don’t worry,” he said. “We all have accidents, Sophie.” Then he bowed at the woman. “Let me introduce you. Sophie, this is Miss Eliot, from the National Childcare Agency. Miss Eliot, this is Sophie, from the ocean.”

The woman sighed—an official sort of sigh, it would have sounded, from Sophie’s place in the sink—and frowned, and pulled clean clothes from a parcel. “Give her to me.”

Charles took the clothes from her. “I took this child from the sea, ma’am.” Sophie watched, with large eyes. “She has nobody to keep her safe. Whether I like it or not, she is my responsibility.”

“Not forever.”

“I beg your pardon?”

“The child is your ward. She is not your daughter.” This was the sort of woman who spoke in italics. You would be willing to lay bets that her hobby was organizing people. “This is a temporary arrangement.”

“I beg to differ,” said Charles. “But we can fight about that later. The child is cold.” He handed the undershirt to Sophie, who sucked on it. He took it back and put it on her. Then he hefted her in his arms, as though about to guess her weight at a fair, and looked at her closely. “You see? She seems a very intelligent baby.” Sophie’s fingers, he saw, were long and thin, and clever. “And she has hair the color of lightning. How could you possibly resist her?”

“I’ll have to come round, to check on her, and I really don’t have the time to spare. A man can’t do this kind of thing alone.”

“Certainly, please do come,” said Charles—and he added, as if he couldn’t stop himself, “if you feel that you absolutely can’t stay away. I will endeavor to be grateful. But this child is my responsibility. Do you understand?”

“But it’s a child! You’re a man!”

“Your powers of observation are formidable,” said Charles. “You are a credit to your optician.”

“But what are you going to do with her?”

Charles looked bewildered. “I am going to love her. That should be enough, if the poetry I’ve read is anything to go by.” Charles handed Sophie a red apple, then took it back and rubbed it on his sleeve until he could see his face in it. He said, “I am sure the secrets of child care, dark and mysterious though they no doubt are, are not impenetrable.”

Charles set the baby on his knee, handed her the apple, and began to read out loud to her from A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

It was not, perhaps, the perfect way to begin a new life, but it showed potential.

2

THERE WAS, IN The O

ffices of The national Childcare Agency in Westminster, a cabinet, and in the cabinet, a red file marked “Guardians: Character Assessment.” In the red file, there was a smaller blue file marked “Maxim, Charles.” It read, “C. P. Maxim is bookish, as one would expect of a scholar—also apparently generous, awkward, industrious. He is unusually tall, but doctors’ reports suggest he is otherwise healthy. He is stubbornly certain of his ability to care for a female ward.”

Perhaps such things are contagious, because Sophie grew up tall and generous and bookish and awkward. By the time she turned seven, she had legs as long and thin as golf umbrellas, and a collection of stubborn certainties.

For her seventh birthday, Charles baked a chocolate cake. It was not an absolute success, because it had sagged in the middle, but Sophie declared loyally that that was her favorite kind of cake. “Because,” she said, “the dip leaves room for more icing. I like my icing to be extragavant.”

“I am glad to hear it,” said Charles. “Although, the word is traditionally pronounced ‘extravagant,’ I believe. Happy probably seventh birthday, dear heart. How about a little birthday Shakespeare?”

Sophie had a habit of breaking plates, and so they had been eating their cake off the front cover of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Now Charles wiped it on his sleeve and opened at the middle. “Will you read me some Titania?”

Sophie made a face. “I’d rather be Puck.” She tried a few lines, but it was slow going. She waited until Charles was looking away, then dropped the book on the floor and did a handstand on it.

Charles laughed. “Bravo!” He applauded against the table. “You look the stuff that elves are made of.”

Sophie fell over into the kitchen table, stood up, and tried again against the door.

“Wonderful! You’re getting better, almost perfect.”

“Only almost?” Sophie wobbled, and squinted at him upside down. Her eyeballs were starting to burn, but she stayed where she was. “Aren’t my legs straight?”

“Almost. Your left knee looks a little uncertain. Anyway, no human is perfect. Nobody since Shakespeare.”

Sophie thought about that later, in bed. “No human is perfect,” Charles had said, but he was wrong. Charles was perfect. Charles had hair the same color as the banister, and eyes that had magic in them. He had inherited his house and all his clothes from his father. They had once been beautiful razzle-dazzle Savile Row one hundred percent silk, and were now fifty percent silk, fifty percent hole. Charles had no musical instruments, but he sang to her, and when Sophie was elsewhere, he sang to the birds, and to the wood lice that occasionally invaded the kitchen. His voice was pitch-perfect. It sounded like flying.

Sometimes the feeling of the sinking ship would come back to Sophie, in the middle of the night, and then she found that she needed desperately to climb things. Climbing was the only thing that made her feel safe. Charles allowed her to sleep on top of the wardrobe. He slept on the floor beneath her, just in case.

Sophie didn’t entirely understand him. Charles ate little, and slept rarely, and he did not smile as often as other people. But he had kindness where other people had lungs, and politeness in his fingertips. If, when reading and walking at the same time, he bumped into a lamppost, he would apologize and check that the lamppost was unhurt.

One morning a week, Miss Eliot came to the house, “to sort out any problems.” (Sophie could have said, “What problems?” but she soon learned to stay silent.) Miss Eliot would look around the house, which was peeling at the corners, and at the spiderwebs in the empty larder, and she would shake her head.

“What do you eat?”

It was true that food was more interesting in their house than in the homes of Sophie’s friends. Sometimes Charles forgot about meat for months at a time. Clean plates seemed to break whenever Sophie came near them, and so he served roast potato chips on atlases of the world, spread open at the map of Hungary. In fact he would have been happy to live on cookies, and tea, and whisky at bedtime. When Sophie had first learned to read, Charles had kept the whisky in a bottle labeled CAT’S URINE, so that Sophie would not touch it, but she had uncorked the bottle and sipped it, and then sniffed at the underside of the cat next door. They were not at all similar, though equally unpleasant.

“We have bread,” said Sophie. “And fish in tins.”

“You have what?” said Miss Eliot.

“I like fish in tins,” said Sophie. “And we have ham.”

“Do you? I’ve never seen a single slice of ham in this place.”

“Every day! Or,” Sophie added, because she was more honest than she found convenient, “definitely sometimes. And cheese. And apples. And I drink a whole pint of milk for breakfast.”

“But how can Charles let you live like that? I don’t think this can be good for a child. It’s not right.”

They managed, in fact, very well, but Miss Eliot never quite understood. When Miss Eliot said “right,” Sophie thought, she meant “neat.” Sophie and Charles did not live neatly, but neatness, Sophie thought, was not necessary for happiness.

“The thing is, Miss Eliot,” said Sophie, “the thing is, I don’t have the sort of face that ever looks neat. Charles says I have untidy eyes. Because of the fleck, you see.” Sophie’s skin was too pale, and it showed blotches in the cold, and her hair had never, in her memory, been without knots. Sophie did not mind, though, because in her memory of her mother she saw the same sort of hair and skin—and her mother, she felt sure, was beautiful. Her mother, she was sure, had smelled of cool air and soot, and had worn trousers with patches at the ankle.

The trousers, in fact, were perhaps the beginning of the troubles. When Sophie was nearing eight years old, she asked Charles for a pair of trousers.

“Trousers? Is that not rather unusual for women?”

“No,” said Sophie. “I don’t think so. My mother wears them.”

“Wore them, Sophie, my child.”

“Wears them. Black ones. But I’d like mine to be red.”

“Um. You wouldn’t prefer a skirt?” He looked worried.

Sophie made a face. “No, I really do want trousers. Please.”

There were no trousers in the shops that would fit her, only the gray shorts that boys wore to school. And, “Good heavens!” said Charles. “You look like a math lesson.” So Charles sewed four pairs himself in brightly colored cotton and gave them to her wrapped in newspaper. One of them had one leg longer than the other. Sophie loved them. Miss Eliot was shocked, and “Girls,” she said, “don’t wear trousers.” But Sophie insisted that they did.

“My mother wears trousers. I know she does. She dances in them, when she plays her cello.”

“She can’t have,” said Miss Eliot. It was always the same. “Women do not play the cello, Sophie. And you were much too young to remember. You must try to be more honest, Sophie.”

“But she did. The trousers were black, and grayish at the knee. And she wore black shoes. I remember.”

“You are imagining things, my dear.” Miss Eliot’s voice was like a window slamming shut.

“But I promise, I’m not.”

“Sophie—”

“I’m not!” Sophie did not add, “You potato-faced old hag!” but she did very much want to. The problem was that a person could not grow up with Charles without becoming polite to her very bones. To be impolite felt, to Sophie, like wearing dirty underwear, but it was difficult to be polite when people talked about her mother. They were so very certain that she was making it up, and she was so very certain that they were wrong.

“Toenail eyes!” whispered Sophie. “Buzzard! I do remember.” She felt a little better.

Sophie did remember her mother, in fact, clear and sharp. She did not remember a father, but she remembered a swirl of hair, and two thin cloth-covered legs kicking to the beat of wonderful music, and that wouldn’t have been possible if the legs had been covered in skirt.

Sophie was also sure she remembered, very clearly, seein

g her mother clinging to a floating door in the middle of the channel.

Everybody said, “A baby is too young to remember.” They said, “You are remembering what you wish were true.” She grew sick of hearing it. But Sophie remembered seeing her mother wave for help. She had heard her mother whistle. Whistles are very distinctive. No matter what the police said, then, she knew her mother had not gone down inside the ship. Sophie was stubbornly certain.

Sophie whispered to herself in the dark every night: “My mother is still alive, and she is going to come for me one day.”

“She’ll come for me,” said Sophie to Charles.

Charles would shake his head. “That is almost impossible, dear heart.”

“Almost impossible means still possible.” Sophie tried to stand up straight and sound adult; people believed you more easily if you were taller. “You always say, ‘Never ignore a possible.’ ”

“But, my child, it is so profoundly improbable that it’s not worth building a life on. It would be like trying to build a house on the back of a dragonfly.”

“She’ll come for me,” said Sophie to Miss Eliot.

Miss Eliot was more blunt. “Your mother is dead. No women survived,” she said. “You mustn’t allow yourself to get carried away.”

Sometimes it seemed difficult for the adults in Sophie’s life to tell between “carried away” and “absolutely correct but unbelieved.” Sophie felt herself flushing. “She will come,” she said. “Or I’ll go to her.”

“No, Sophie. That is not how the world works.” Miss Eliot was sure that Sophie was mistaken, but then Miss Eliot was also sure that cross-stitch was vital, and Charles was impossible, which just showed that adults weren’t always right.

One day Sophie found some red paint and wrote the name of the ship, the Queen Mary, and the date of the storm on the white wall of the house, just in case her mother passed by.

Charles’s face, when he found her, was too complicated for her to look at. But he helped her reach the high parts and wash the brushes afterward.

“A case,” he said to Miss Eliot, “of the just in cases.”