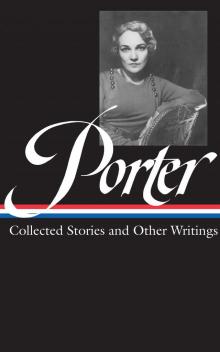

The Collected Stories of Katherine Anne Porter

Katherine Anne Porter

Katherine Anne Porter

COLLECTED STORIES AND OTHER WRITINGS

T H E L I B R A R Y O F A M E R I C A

Volume compilation, notes, and chronology copyright © 2008 by Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., New York, N.Y.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced commercially by offset-lithographic or equivalent copying devices without the permission of the publisher.

The Collected Stories of Katherine Anne Porter copyright © 1944, 1941, 1940, 1939, 1937, 1936, 1935, 1934, 1930, renewed 1972, 1969, 1968, 1967, 1965, 1963, 1962, 1958 by Katherine Anne Porter. “Virgin Violeta” and “The Martyr” copyright © 1924, 1923 by Century Magazine, renewed 1951, 1950 by Meredith Publishing Company. “Hacienda” copyright 1934 by Harrison of Paris. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

All other selections reprinted with the permission of The Katherine Anne Porter Foundation.

THE LIBRARY OF AMERICA, a nonprofit publisher, is dedicated to publishing, and keeping in print, authoritative editions of America’s best and most significant writing. Each year the Library adds new volumes to its collection of essential works by America’s foremost novelists, poets, essayists, journalists, and statesmen.

If you would like to request a free catalog and find out more about The Library of America, please visit www.loa.org/catalog or send us an e-mail at [email protected] with your name and address. Include your e-mail address if you would like to receive our occasional newsletter with items of interest to readers of classic American literature and exclusive interviews with Library of America authors and editors (we will never share your e-mail address).

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2008927625

ISBN 978–1–59853–029–2 (print)

ISBN 978–1–59853–326–2 (kindle)

First Printing

The Library of America—186

DARLENE HARBOUR UNRUE

IS THE EDITOR OF THIS VOLUME

Contents

THE COLLECTED STORIES OF KATHERINE ANNE PORTER

Go Little Book. . .

FLOWERING JUDAS AND OTHER STORIES

María Concepción

Virgin Violeta

The Martyr

Magic

Rope

He

Theft

That Tree

The Jilting of Granny Weatherall

Flowering Judas

The Cracked Looking-Glass

Hacienda

PALE HORSE, PALE RIDER

Old Mortality

Noon Wine

Pale Horse, Pale Rider

THE LEANING TOWER AND OTHER STORIES

The Old Order

The Source

The Journey

The Witness

The Circus

The Last Leaf

The Fig Tree

The Grave

The Downward Path to Wisdom

A Day’s Work

Holiday

The Leaning Tower

ESSAYS, REVIEWS, AND OTHER WRITINGS

“I needed both. . .”

CRITICAL

The Days Before

Reflections on Willa Cather

A Note on The Troll Garden

Gertrude Stein: Three Views

“Everybody Is a Real One”

Second Wind

The Wooden Umbrella

“It Is Hard to Stand in the Middle”

Eudora Welty and A Curtain of Green

The Wingèd Skull

On a Criticism of Thomas Hardy

E. M. Forster

Virginia Woolf

D. H. Lawrence

Quetzalcoatl

A Wreath for the Gamekeeper

“The Laughing Heat of the Sun”

The Art of Katherine Mansfield

The Hundredth Role

Dylan Thomas

“A death of days. . .”

“A fever chart. . .”

“In the morning of the poet. . .”

A Most Lively Genius

Orpheus in Purgatory

In Memoriam

Ford Madox Ford (1873–1939)

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Sylvia Beach (1887–1962)

Flannery O’Connor (1925–1964)

PERSONAL AND PARTICULAR

On Writing

My First Speech

“I must write from memory. . .”

No Plot, My Dear, No Story

“Writing cannot be taught. . .”

The Situation of the Writer

The Situation in American Writing

Transplanted Writers

The International Exchange of Writers

The Author on Her Work

No Masters or Teachers

On “Flowering Judas”

“The only reality. . .”

“Noon Wine”: The Sources

Notes on the Texas I Remember

Portrait: Old South

A Christmas Story

Audubon’s Happy Land

The Flower of Flowers

A Note on Pierre-Joseph Redouté

A House of My Own

The Necessary Enemy

“Marriage Is Belonging”

A Defense of Circe

St. Augustine and the Bullfight

Act of Faith: 4 July 1942

The Future Is Now

The Never-Ending Wrong

Afterword

MEXICAN

Why I Write About Mexico

Reports from Mexico City,

The New Man and the New Order

The Fiesta of Guadalupe

The Funeral of General Benjamín Hill

Children of Xochitl

The Mexican Trinity

Where Presidents Have No Friends

In a Mexican Patio

Leaving the Petate

The Charmed Life

Corridos

Sor Juana: A Portrait of the Poet

Notes on the Life and Death of a Hero

A Mexican Chronicle, 1920–1943

Blasco Ibanez on “Mexico in Revolution”

Paternalism and the Mexican Problem

La Conquistadora

¡Ay, Que Chamaco!

Old Gods and New Messiahs

Diego Rivera

These Pictures Must Be Seen

Rivera’s Personal Revolution

Parvenu. . .

History on the Wing

Thirty Long Years of Revolution

AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL

About the Author

The Land That Is Nowhere

Chronology

Note on the Texts

Notes

Index

THE COLLECTED STORIES OF KATHERINE ANNE PORTER

Go Little Book. . .

THIS collection of stories has been floating around the world in many editions, countries and languages, in three small volumes, for many years. There are four stories added which have never been collected before, and it is by mere hazard they are here at all. “The Fig Tree,” now in its right place in the sequence called The Old Order, simply disappeared at the time The Leaning Tower was published, in 1944, and reappeared again from a box of otherwise unfinished manuscripts in another house, another city and a different state, in 1961. “Holiday” represents one of my prolonged struggles, not with questions of form or style, but my own moral and emotional collision with a human situation I was too young to cope with at the time it occurred; yet the story haunted me for years and I made three separate versions, with a certain spot in all three where the thing went off track.

So I put it away and it disappeared also, and I forgot it. It rose from one of my boxes of papers, after a quarter of a century, and I sat down in great excitement to read all three versions. I saw at once that the first was the right one, and as for the vexing question which had stopped me short long ago, it had in the course of living settled itself so slowly and deeply and secretly I wondered why I had ever been distressed by it. I changed one short paragraph and a line or two at the end and it was done. “María Concepción” was my first published story. It was followed by “Virgin Violeta” and “The Martyr,” all stories of Mexico, my much-loved second country, and they were each in turn accepted and published in the old Century Magazine, now vanished, by good generous sympathetic Carl Van Doren. He was the first editor—indeed, the first person—to read a story of mine, and I remember how unhesitatingly and warmly he said, “I believe you are a writer!” This was in 1923.

Several writers or persons connected with literature in some way or another, from time to time in published reminiscences, have done me the honor to mention that they had, so to speak, “discovered” me.

There is no reason to name them, but I shall only say here and now, to have the business straight, it was Carl Van Doren, gifted writer, editor and resourceful friend to young writers, who just lightly tossed my stories into print and started me on my long career, with such an air of it being all in the day’s work, which it was, I went away in a dazzle of joy, not in the least thinking of myself as “discovered”—I had known where I was all along—nor looking towards the future as a “career.” What unpleasant words they are in this context. “Virgin Violeta” and “The Martyr” were left out of the first edition, I forget why, possibly oversight. A friend fished them out of the ancient Century files, got them re-published, after forty-odd years, and so they join their fellows. Every story I ever finished and published is here. I beg of the reader one gentle favor for which he may be sure of my perpetual gratitude: please do not call my short novels Novelettes, or even worse, Novellas. Novelette is classical usage for a trivial, dime-novel sort of thing; Novella is a slack, boneless, affected word that we do not need to describe anything. Please call my works by their right names: we have four that cover every division: short stories, long stories, short novels, novels. I now have examples of all four kinds under these headings, and they seem very clear, sufficient, and plain English.

To part is to die a little, it is said (in every language I can read), but my farewell to these stories is a happy one, a renewal of their life, a prolonging of their time under the sun, which is what any artist most longs for—to be read, and remembered.

Go little book. . . .

KATHERINE ANNE PORTER

14 June 1965

Contents

Go Little Book. . .

Flowering Judas and Other Stories

María Concepción

Virgin Violeta

The Martyr

Magic

Rope

He

Theft

That Tree

The Jilting of Granny Weatherall

Flowering Judas

The Cracked Looking-Glass

Hacienda

Pale Horse, Pale Rider

Old Mortality

Noon Wine

Pale Horse, Pale Rider

The Leaning Tower and Other Stories

The Old Order

THE SOURCE

THE JOURNEY

THE WITNESS

THE CIRCUS

THE LAST LEAF

THE FIG TREE

THE GRAVE

The Downward Path to Wisdom

A Day’s Work

Holiday

The Leaning Tower

FLOWERING JUDAS AND OTHER STORIES

María Concepción

MARÍA CONCEPCIÓN walked carefully, keeping to the middle of the white dusty road, where the maguey thorns and the treacherous curved spines of organ cactus had not gathered so profusely. She would have enjoyed resting for a moment in the dark shade by the roadside, but she had no time to waste drawing cactus needles from her feet. Juan and his chief would be waiting for their food in the damp trenches of the buried city.

She carried about a dozen living fowls slung over her right shoulder, their feet fastened together. Half of them fell upon the flat of her back, the balance dangled uneasily over her breast. They wriggled their benumbed and swollen legs against her neck, they twisted their stupefied eyes and peered into her face inquiringly. She did not see them or think of them. Her left arm was tired with the weight of the food basket, and she was hungry after her long morning’s work.

Her straight back outlined itself strongly under her clean bright blue cotton rebozo. Instinctive serenity softened her black eyes, shaped like almonds, set far apart, and tilted a bit endwise. She walked with the free, natural, guarded ease of the primitive woman carrying an unborn child. The shape of her body was easy, the swelling life was not a distortion, but the right inevitable proportions of a woman. She was entirely contented. Her husband was at work and she was on her way to market to sell her fowls.

Her small house sat half-way up a shallow hill, under a clump of pepper-trees, a wall of organ cactus enclosing it on the side nearest to the road. Now she came down into the valley, divided by the narrow spring, and crossed a bridge of loose stones near the hut where María Rosa the beekeeper lived with her old godmother, Lupe the medicine woman. María Concepción had no faith in the charred owl bones, the singed rabbit fur, the cat entrails, the messes and ointments sold by Lupe to the ailing of the village. She was a good Christian, and drank simple herb teas for headache and stomachache, or bought her remedies bottled, with printed directions that she could not read, at the drugstore near the city market, where she went almost daily. But she often bought a jar of honey from young María Rosa, a pretty, shy child only fifteen years old.

María Concepción and her husband, Juan Villegas, were each a little past their eighteenth year. She had a good reputation with the neighbors as an energetic religious woman who could drive a bargain to the end. It was commonly known that if she wished to buy a new rebozo for herself or a shirt for Juan, she could bring out a sack of hard silver coins for the purpose.

She had paid for the license, nearly a year ago, the potent bit of stamped paper which permits people to be married in the church. She had given money to the priest before she and Juan walked together up to the altar the Monday after Holy Week. It had been the adventure of the villagers to go, three Sundays one after another, to hear the banns called by the priest for Juan de Dios Villegas and María Concepción Manríquez, who were actually getting married in the church, instead of behind it, which was the usual custom, less expensive, and as binding as any other ceremony. But María Concepción was always as proud as if she owned a hacienda.

She paused on the bridge and dabbled her feet in the water, her eyes resting themselves from the sun-rays in a fixed gaze to the far-off mountains, deeply blue under their hanging drift of clouds. It came to her that she would like a fresh crust of honey. The delicious aroma of bees, their slow thrilling hum, awakened a pleasant desire for a flake of sweetness in her mouth.

“If I do not eat it now, I shall mark my child,” she thought, peering through the crevices in the thick hedge of cactus that sheered up nakedly, like bared knife blades set protectingly around the small clearing. The place was so silent she doubted if María Rosa and Lupe were at home.

The leaning jacal of dried rush-withes and corn sheaves, bound to tall saplings thrust into the earth, roofed with yellowed maguey leaves flattened and overlapping like shingles, hunched drowsy and fragrant in the warmth of noonday. The hives, similarly made, were scattered towards the back of the clearing, like small mounds of clean vegetable refuse. Over each mound there hung a dusty golden shimmer of bees.

A light gay scream of laughter rose from behind the hut; a man’s short laugh joined in. “Ah, hahahaha!” went the voices together high and low, like a song.

&nbs

p; “So María Rosa has a man!” María Concepción stopped short, smiling, shifted her burden slightly, and bent forward shading her eyes to see more clearly through the spaces of the hedge.

María Rosa ran, dodging between beehives, parting two stunted jasmine bushes as she came, lifting her knees in swift leaps, looking over her shoulder and laughing in a quivering, excited way. A heavy jar, swung to her wrist by the handle, knocked against her thighs as she ran. Her toes pushed up sudden spurts of dust, her half-raveled braids showered around her shoulders in long crinkled wisps.

Juan Villegas ran after her, also laughing strangely, his teeth set, both rows gleaming behind the small soft black beard growing sparsely on his lips, his chin, leaving his brown cheeks girl-smooth. When he seized her, he clenched so hard her chemise gave way and ripped from her shoulder. She stopped laughing at this, pushed him away and stood silent, trying to pull up the torn sleeve with one hand. Her pointed chin and dark red mouth moved in an uncertain way, as if she wished to laugh again; her long black lashes flickered with the quick-moving lights in her hidden eyes.

María Concepción did not stir nor breathe for some seconds. Her forehead was cold, and yet boiling water seemed to be pouring slowly along her spine. An unaccountable pain was in her knees, as if they were broken. She was afraid Juan and María Rosa would feel her eyes fixed upon them and would find her there, unable to move, spying upon them. But they did not pass beyond the enclosure, nor even glance towards the gap in the wall opening upon the road.

Juan lifted one of María Rosa’s loosened braids and slapped her neck with it playfully. She smiled softly, consentingly. Together they moved back through the hives of honey-comb. María Rosa balanced her jar on one hip and swung her long full petticoats with every step. Juan flourished his wide hat back and forth, walking proudly as a game-cock.

María Concepción came out of the heavy cloud which enwrapped her head and bound her throat, and found herself walking onward, keeping the road without knowing it, feeling her way delicately, her ears strumming as if all María Rosa’s bees had hived in them. Her careful sense of duty kept her moving toward the buried city where Juan’s chief, the American archaeologist, was taking his midday rest, waiting for his food.