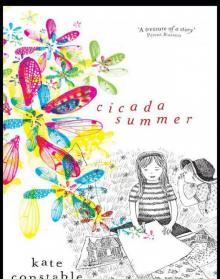

Cicada Summer

Kate Constable

cicada

summer

‘Makes you believe anything is possible.

My skin prickled, my pulse raced and I couldn't

put the book down until I'd finished.’ Glenda Millard

‘A treasure of a story, a stoty to slip into your

pocket like a feather or a perfectly round stone

–for keeps.’ Penni Russon

cicada

summer

kate

constable

First published in 2009

Copyright © Kate Constable, 2009

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or ten per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander St

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Constable, Kate, 1966–

Cicada summer/Kate Constable.

9781741758283 (pbk.)

A823.4

Cover and text design by Design by Committee

Cover illustration by Ali Durham

Set in 12/17 pt Baskerville by Midland Typesetters, Australia

Printed in Australia by McPherson’s Printing Group

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Jan and Bill, with love

CONTENTS

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

About The Author

1

Eloise floated on a sea of red and orange swirls. Dazzling golden threads shimmered through the cloth, the tiny fish embroidered on Mum’s favourite skirt. Mum’s arms were around her and Mum was singing softly.

. . . and little fishes, way down below, wiggle their tails, and away they go . . .

She was falling asleep on Mum’s lap, safe and warm, wrapped in the billows of her skirt. The red and gold and purple of memory enfolded her and floated her away.

‘Wake up, El for Leather!’

Eloise’s eyes sprung open, and she struggled upright. A sheet of white light flashed from the rear window of the car in front, blinding her. She shut her eyes again and watched a dark shape drift down the inside of her eyelids, then jump up again, over and over, endlessly receding but never quite fading away.

Mum.

‘Can’t dream your whole life away!’ cried Dad. ‘You’re not a little girl any more. High school next year. This is a fresh start, a fresh start for both of us. You can’t move forward if you’re always looking back . . .’

Eloise gazed at the passing landscape: parched paddocks, a harsh blue sky, dead trees. She shrank from it. Inside the car it was cool, but outside it was shimmering hot.

‘Hel-lo, dreamy? Did you hear a word I said, El Dorado? Do you even know where we’re going?’

Of course she knew. They were moving to the country, to the town of Turner where Dad grew up. He was building a convention centre; or maybe it was a hotel? It was hard to keep up with all his plans. There had been so many of them in the last couple of years, and they changed so quickly.

Eloise’s grandmother Mo lived in Turner, she knew that much, though she couldn’t remember meeting her. Mo and Dad had had a big fight years ago. And then she hadn’t come to Mum’s funeral, Dad had been so angry about that.

Eloise tried not to think about the funeral. She tried not to think about Mum. The red and golden swirls of Mum’s skirt, the whisper of Mum’s voice in her ear . . .

Eloise dropped a thick black curtain down on all those thoughts and smothered them.

Dad was humming along to the radio, tapping his hands on the wheel. He broke off to glance across at Eloise. ‘Everything’s going to work out perfectly this time. We’ll settle down for good. This town’s ripe for a convention centre . . .’ And he was off again at top speed.

But it didn’t matter if Eloise was convinced or not. Dad would do what he wanted anyway, like he always did. Since Mum died, Dad had quit jobs, moved cities, found girlfriends and left them. Bree was the latest; she and Dad had had a big fight last week. Dad had dragged Eloise out of bed and they’d gone to a hotel. Then he’d sweet-talked away five years of not speaking to Mo, and now they were going to visit her.

Eloise watched as the road signs beside the highway counted down the kilometres to Turner: 42, 29, 17, 8. Then all at once they were there, crawling down the main street. A line of trees marched along the middle of the road, casting black bars of shadow on the tarmac. A stone soldier leaned on his gun and gazed off across hills baked yellow in the sun.

‘Still pretty,’ said Dad. ‘Even prettier once it gets a drop of rain. There’s the river, the hills, the national park. Look at the shops. How’s that for picturesque? And only—’ Dad glanced at his watch. ‘Only two hours from the city, give or take. Perfect for conferences, team-building weekends, you name it; they’ll come rolling in.’ He cocked his head toward Eloise. ‘What do you say, Ella Fitzgerald, should we go and take a look at the building site? Mo’s expecting us for lunch, but I never said it’d be an early lunch. And it’s not like she’s got anything to rush off to.’

Eloise was relieved. She wanted to put off meeting Mo as long as possible.

Dad swung the car off the main street and up a side road with a red-brick church at the top of a hill. ‘Besides, knowing Mo, she’ll have a million questions, and I don’t know about you, but I’m not in the mood for an interrogation. Not today, not today,’ he sang. ‘Don’t frighten me away, or I won’t want to stay; don’t ask me any questions today . . . Left at the church, then third turn on the right, if memory serves.’

Eloise counted the turn-offs as they passed. The dusty road dipped and rose between dry fields dotted with black and white cows.

‘Here it is. The human compass strikes again!’

With a triumphant flourish, Dad steered the red sports car between a pair of sagging iron gates hung with a sign: PRIVATE PROPERTY. NO TRESPASSERS.

They bumped down a rutted driveway shaded with pine trees, a murky tunnel carpeted with brown needles. A tangle of overgrown trees and bushes rose before them as the car jolted around a curve and out onto a wide gravel drive splotched with weeds.

Dad switched off the engine and there was a sudden silence. ‘There it is.’

It was a house. Eloise hadn’t known there was a house.

She stepped out of the car into the heat, and stared. She’d never seen a house like this before. It was made of concrete, with wide windows and rounded corners, and balconies with slim iron railings. It looked more like a small ocean liner than a house; there were even round porthole windows. The shabby once-white walls were stained with green and streaked with rust. A double set of curved steps swerved apart then swooped together to meet at the double front doors.

‘Art Deco, 1931.’ Dad pointed to a pattern of stiff sculpted zigzags and wave shapes moulded t

o the wall. ‘House looks like a flaming Christmas cake. But the land – the land’s worth a fortune.’

He snapped open his mobile phone and began to take photos of the garden. He backed away round the side of the building, holding the phone out in front of him. Eloise watched him disappear, then, slowly, she climbed the steps to the front door. Two long glass panels ran down either side of it, etched with patterns of diagonal lines and triangles that weaved over and under.

Eloise turned and gazed out over the garden. It was as big as a park, but all tangled and neglected; weeds swarmed everywhere and the trees crowded round the house as if they were trying to press their way inside. A warm wind blew through Eloise’s hair and her scalp prickled. She swung round sharply, but no one was there.

‘Hey, Elastic Band!’ Dad called from the rear of the house, and Eloise went to find him.

A paved terrace laced with dandelions ran along the back of the house; big windows and glass doors overlooked a gentle slope overgrown with yellow grass. Plywood was nailed across one smashed window. At the far end of the terrace was a covered porch, where Dad stood beside an open door.

‘Human compass, human key.’ Dad rubbed his shoulder. ‘Is there anything this man can’t do? Want to take a look inside?’

Eloise hung back. The inside of the house looked dark and creepy.

‘Come on. You’re not scared, are you?’ Dad wiggled his fingers and woooed like a ghost. He laughed uneasily and wiped his forehead with his arm. ‘Come on, Elementary. Chop chop. I’ll be right behind you.’

Reluctantly Eloise stepped over the threshold.

She walked into a back passageway with rooms opening off on either side. The air was cool and stale and still. The rooms were shadowy, dim and green – an underwater kind of light – and there was a pungent musty smell.

Dad sniffed. ‘Mice.’

Eloise took a hasty step backward, but Dad prodded her on.

‘Not scared of a wittle mousie, are you? All old houses have mice . . . My convention centre won’t have mice, I can promise you that.’ Dad laughed suddenly and spread his arms wide. ‘I’ve always wanted to get my hands on this place! I can do anything now – I could open a damn zoo if I felt like it! That idiot Mitchell, flaming Bree, think I can’t follow through. I’ll show ’em. Everything’s going to change now, Elbow Grease, you know that, don’t you? This time it’s going to work out . . .’

His voice trailed away and he gazed into space, as if he could see the future unfolding before his eyes.

Eloise stepped deeper into the dimness. A ceaseless rustle of leaves, like scraps of paper tossed by the hot wind, whispered from the distant garden. A cicada started up somewhere near the porch.

At the end of the passage, Eloise pushed through a door covered in moth-eaten green felt and found herself in the grand foyer by the front door. A wide white staircase circled up to the next floor, and a round gallery looked down over the entrance hall. Eloise glimpsed big empty rooms opening out, one into another, like the chambers of a seashell. The black and white tiles and the zigzag patterns around the edges of the floor were furry with dust, and so were the stiff scalloped wave-shapes and zigzags moulded into the ceiling. Cobwebs drooped from the iron stair-railings.

As Eloise neared the front doors, the sun shifted and blazed through the glass panels, lighting the floor with a pattern of lines and angles. Eloise reached out and caught a tiny triangle of light in the palm of her hand.

Then the sun faded, and the foyer became a cave of shifting shadows. All the noises faded too – her father’s muffled footsteps, the restless wind – and Eloise stood in a pool of silence.

Something flickered at the top of the stairs.

The back of Eloise’s neck went cold. She wanted to run, but she couldn’t move. She heard a voice call, I’m coming!, and a girl in a pale dress and a big sunhat came running down the stairs, her fingertips slipping down the curve of the slim iron railing.

Eloise couldn’t breathe, her mouth was dry. She couldn’t even run away.

But at the bottom of the steps, the girl in the pale dress faltered and stopped. For a fraction of a second she stood motionless, as if she were listening, then all at once she turned and stared straight at Eloise.

Their eyes met. Eloise tried to swallow; she backed away, one step, then another. And suddenly the foyer was empty. The ghostly girl was gone.

All the sounds came rushing back to full volume: the sighs and whispers of the garden, the shrill of cicadas, creaks and slams from the kitchen, Dad’s brisk boots stomping up behind her. ‘There you are, Elephant! What’s up? Did a mouse run over your foot?’

Eloise managed to shake her head.

‘So what do you reckon? Bit dark and stinky, isn’t it. Paradise for the mice! Can you believe we’ve been here for an hour? Time ran away on me. We’d better head off; we’re late for Mo. Better not make her cranky. You know this was her place, don’t you? She hasn’t lived here for years though – obviously. All mine now.’ Dad grinned. ‘Very generous of her to sign it over, so make sure you look grateful,

El’s Bells. Of course, it’s way too big for her to manage, and it would have been mine sooner or later anyway. Family property. And we’re the only family, you and me, so—’

Dad kept talking all the way back to the car, but Eloise hardly heard him. She felt dizzy. She buckled her seatbelt as Dad spun the car around with a spray of gravel. Her head was turned toward the window but all she could see was the figure of the ghostly girl. Like a video replaying in her mind, she saw the girl run down the stairs, stop and turn to stare at Eloise. Run, stop, turn – over and over. Eloise shivered. She wished she could sit somewhere with her pencils and paper and draw what she’d seen. Already the picture in her mind had begun to waver and blur. Drawing it would fix it, pin it down. She shut her eyes and tried to print the memory on the inside of her eyelids.

‘Great location, heaps of potential.’ Dad was still talking. ‘Don’t know if it’s worth trying to keep any of the garden in this drought. It looks half-dead already. But we’ll see. Just you wait, Electric Chair. It’s going to be magnificent.’

Eloise nodded, but Dad wasn’t looking. A shiver ran through her and she hugged herself. She twisted her head to catch one last glimpse of the pale shape of the house, gradually swallowed up by the trees; like a ship slowly sinking beneath the waves.

2

Here we are.’ Dad pulled into Mo’s driveway. He parked in front of the garage and switched off the engine, but then he just sat there; he didn’t get out of the car.

The small house where Mo lived couldn’t have been more different from the big white dilapidated mansion they’d just left behind. It was dark and low-roofed, hunched close to the ground. Faded striped awnings were lowered over the windows. The house seemed to scowl at the ground. Instead of neat beds of roses and azaleas, like most of the neighbours, Mo’s yard was crammed with prickly native bushes. The neighbours’ squares of lawn were all dead from the drought, but these prickly bushes struggled on.

The front door slowly opened. Eloise could just see a dark shape behind the screen door. A voice called out sharply from inside the house, ‘You took your time! I was expecting you at one; it’s nearly half-past two.’

‘That’s a fine greeting for the prodigal son.’ Dad slammed the car door and glared toward the invisible figure. ‘Come on, Elf Ears, she won’t bite.’

Eloise slipped out of the car and followed Dad inside. Mo stepped back just far enough to let them in and then shut the door. She stood in the middle of the hallway with her fists on her hips. There was nothing ghostly about Mo. Her grey, wiry hair stood out in tufts like steel wool, and her eyes glittered suspiciously in her gaunt, bony face. One pair of glasses dangled round her neck, and another was shoved up on top of her wild tangle of hair. She wore a striped apron with a mud-coloured shirt and trousers underneath. Eloise’s eyes went wide. Mo was clutching a knife, and her hands dripped with blood.

‘Don’t flin

ch. What are you, a kitten? It’s only beetroot. Am I going to get a kiss from my only grandchild? Come on, get it over with. Save us, you’re not some kind of shrinking violet, are you?’

Mo rammed on her glasses and peered sharply at Eloise.

‘She’s a bit shy, that’s all. She’s fine once she warms up, aren’t you, Elevator Music?’ Dad put his arm round Eloise’s shoulders; he sounded so easy and confident that for a second Eloise almost believed it too.

Mo sniffed, testing the tip of the knife on her finger. ‘She’s a shrimp of a thing, isn’t she? Looks more like ten than— How old are you now? Twelve, thirteen? Inherited the McCredie hair, poor kid. Got her mother’s eyes though.’ There was a pause, then Mo said, ‘Sorry I couldn’t make it to the funeral.’

Dad’s arm tightened around Eloise. He didn’t like talking about Mum. ‘That’s all water under the bridge now. What’s done is done. Time to move on.’ There was another pause. ‘Sorry we’re late. Stopped to have a look at the property.’

Mo sniffed again. ‘Hope it lived up to expectations.’

‘It’s a fantastic piece of real estate. Pity the house is such an eyesore.’

Mo bristled for a second, then she looked away. ‘Not my problem any more,’ she said brusquely.

‘All yours. Best thing I’ve ever done, get rid of that old place. And all its ghosts.’

Eloise jumped.

‘Speaking metaphorically, of course.’ Mo turned to her. ‘Hungry? Like beetroot?’

After a second Eloise nodded. Her heart thudded, then slowed. Mo couldn’t know what she’d seen at the house, could she?

‘Cat got your tongue? She can speak, can’t she, Stephen?’

‘Of course she can. Could we move out of the doorway, do you think? Or would you prefer we got back in the car?’

‘No need to get your knickers in a knot,’ snapped Mo, and moved down the hallway. Bright purple-red spots had dripped all over the floor. Mo pointed down the corridor with a gory hand. ‘Dining room. That is, if you still want the lunch I lovingly prepared for you three hours ago. I’ve had mine. Got tired of waiting.’