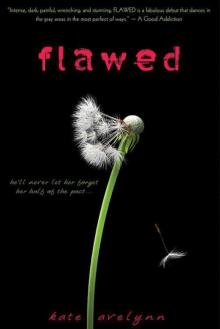

Flawed

Kate Avelynn

Flawed

Kate Avelynn

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is coincidental.

Copyright © 2012 by Kate Avelynn. All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce, distribute, or transmit in any form or by any means. For information regarding subsidiary rights, please contact the Publisher.

Entangled Publishing, LLC

2614 South Timberline Road

Suite 109

Fort Collins, CO 80525

Visit our website at www.entangledpublishing.com.

Edited by Liz Pelletier

Cover design by Heather Howland

Print ISBN 978-1-62061-232-3

Ebook ISBN 978-1-62061-236-1

Manufactured in the United States of America

First Edition November 2012

The author acknowledges the copyrighted or trademarked status and trademark owners of the following wordmarks mentioned in this work of fiction: You Are My Sunshine; Godsmack; Super Clips; Dumpster; FedEx; U-Haul; Slice of Heaven; Chef Boyardee; Survivorman; Popsicle; Tupperware; Tilt-a-Whirl; Ferris Wheel; Magic Mountain; Disneyland; iPod; DayGlo; Slip ’N Slide.

For JD, who always believes in me,

even when I don’t believe in myself.

One

My first memory of James is what keeps me here, smoothing hair out of a boy’s blood-spattered face. The sirens screaming in the distance are too late.

They’re always too late.

Forehead pressed to his, I choke on the burnt stench of gunpowder and try to hum the lullaby James used to sing to me.

You are my sunshine, my only sunshine…

James is why I never left.

I should have left.

Two

I remember the tiny, white flowers that dotted our neighbor’s lawn and how my body sank into the lush grass like it was made of pillows. I remember the way the sun baked my exposed skin and the tiny insects and dandelion seeds danced around me on the soft summer breeze. I remember my white, cotton dress, the only sleeveless, legless item of clothing I’d ever owned.

Mrs. Baxter gave it to me as an Easter present a few days before my seventh birthday, leaving it on the porch, folded and wrapped in a pink ribbon. James snuck it into our room before our father saw, and helped me tie the white sash sewn onto the waist.

I remember sitting on Mrs. Baxter’s lawn hoping she’d see me in it because I was too shy to knock on the front door and thank her. I remember wishing I knew how to tie bows as well as James so I could have worn that pretty pink ribbon in my hair.

I remember my father’s calloused hand clamping down on my shoulder.

He dragged me inside, out of the sunshine and into the dark dungeon of our house. Two of my dolls were lying in front of the television in the living room. My carelessness normally would’ve cost me the dolls, but not that day. Not when the sharp bite of beer hung in the air and clung to his rumpled weekend clothes. My hands flew out to break my fall a second too late.

“How many times’ve I told you not to leave your shit on the floor? Huh, Sarah?”

“I’m sorry!” I scrabbled across the worn carpet, gathered up the dolls, and clutched them to my chest, but it didn’t matter. He had already unbuckled his dreaded belt and was pulling it through his belt loops.

“Yeah? You’re about to be a whole lot sorrier.”

The stinging slap of leather against skin reverberated off the dingy walls. Once, twice, three times. I bit my lip and tried not to cry out because crying out only ever made things worse.

The blows stopped abruptly. “Get your ass back in your room or this is gonna be a whole lot worse!” he bellowed down the hall. “I’m not warning you again!”

A door clicked shut. My mother’s door.

The pound-pound-pound of my brother barreling into the room filled the void she left behind. From where I lay curled on the floor, my brother looked like an angel.

“Don’t touch her!”

This is my first real memory of James. In every memory before that, he’s just a flash of color, a warm body with a blurred face, a comforting voice begging me not to die. When he planted himself between our father and me that day, an eight-year-old with small fists clenched at his sides, I think I fell in love with my brother.

Our father sneered at him. “Do you think I’m scared of you, boy?”

James lifted his chin. “You should be.” But even I heard the waver in his voice.

“You little shit.”

I scrambled back into the dining room, dolls forgotten, mouth open in a silent scream as my brother took what was left of the punishment meant for me. It ended when the back of our father’s hand sent him sprawling to the floor. Before James could get to his feet, our father staggered toward the garage and the refrigerator of beer waiting for him.

James crawled over to where I lay curled up beneath the dining room table and dragged me into his arms. There was blood on his lip and one of his eyes had started to swell. “Shh,” he murmured. “He’s gone. Everything’s okay now.”

I tried to dab his lip with the torn hem of my dress, but he gently pushed my hand away. “I’m okay,” he said. “You’re hurt worse than me anyway.”

I could feel the welts rising on my back and arms. “You saved me,” I sobbed into his sleeve. “You saved me.”

“I’m never gonna let anything happen to you, Sarah.”

“I won’t let anything happen to you, too.”

He smiled, all dimples and sparkling blue eyes. “Nah, you’re too little. Just don’t leave me, okay? Not ever. Promise?”

“I promise.”

We stayed huddled together under the table for as long as we dared, James holding me and quietly singing our lullaby, me watching the door that led to the garage.

You are my sunshine, my only sunshine.

You make me happy when skies are gray.

You’ll never know, dear, how much I love you.

Please don’t take my sunshine away.

James, the savior. That’s the image of my brother I clung to.

Still cling to.

Three

Eleven years later…

I’m probably the only person in school that dreads the final bell before summer vacation. Summer for me equals ten weeks of wandering around town or hiding in my room with the door locked, hoping against hope my father will work extra hours at the paper mill and James will work less.

From my desk in the back of the room, I watch my classmates swap yearbooks for the last time as they walk out the door, happily chattering about the usual lake parties and summer jobs and hour-long road trips down into California. They don’t notice me, the skinny girl with stringy hair and eyes too big for her head. They don’t ask me to come along or wonder aloud why I don’t have a yearbook for people to sign. I’ve made it a point to be invisible.

The room clears within seconds. The seniors got out three days ago, so it’s like everyone is in a hurry to join them. Even my American Lit teacher, Mr. Carter, seems eager to escape to wherever teachers spend their summers. Maybe I’ll stay in my seat until the janitor kicks me out, or maybe I’ll move from room to room until he locks all the doors and I have nowhere else to go.

The school is probably peaceful at night.

I can’t stay, though. I won’t. James gets off work early on Fridays—four instead of four thirty, a whole half an hour before our father—and I don’t dare worry James by not being there when he shows up. He already worries too much. Plus, he’s always starving when he gets home, and he’ll burn the house down if someone’s not there to guard the stove.

And then there’s our fa

ther. He expects dinner ready and waiting.

With a sigh, I heft my backpack onto one shoulder and trudge into the hallway, empty save for open lockers and leftover papers that flutter and scrape across the linoleum on the breeze coming through the open doors. Out in the parking lot, cars honk and engines rev as my classmates spill into the streets. Their freedom tastes sweet on the air. I breathe it in and wish it was mine, too.

Next year it will be. James and I are moving out the second I graduate—three-hundred and-sixty-three days from now—that’s the promise he makes every time something bad happens. He’s been saving the money he makes at the mill for almost a year now while I write out budgets, and fish the Sunday paper out of the neighbor’s plastic recycling bin every week to look for places we can rent. So far, we haven’t found anything cheap enough.

I cannot wait until we do.

After glancing at my watch, I decide to take the long way home, the one that winds through the nicer neighborhoods east of school, past the seventeen stores that make up the Granite Falls strip mall, and into the park just outside the paper mill’s gates. It’s deserted, of course. No one goes there because of the gritty haze that drifts down from the stacks and coats the trees in a layer of silt. Our neighborhood is two blocks past the park, and once I skirt the pond and pass the picnic tables, I can see our street.

It’s 3:42. And by the time I get to our driveway, I still have thirteen minutes to get dinner started. Perfect.

It’s hard to ignore the peeling beige paint on our house. This isn’t a “nice” neighborhood by any stretch of the imagination, but nobody else has a house that flakes paint like dandruff.

The low hum of my mother’s television and fresh cigarette smoke greets me when I step into the kitchen. I close the door quietly and hope she doesn’t hear the click. Some days, when there isn’t any smoke and the house is too quiet, I creep down the hall and listen for her breathing. It’s a weird feeling coming home from school, wondering if this is the day I’ll find my mother’s dead body. Part of me is terrified of that happening. The other part—the darker half of my heart I keep smothered for James’s sake—wishes she’d just overdose and be done with it.

After tossing my stuff into my bedroom, I head back to the kitchen, grab a pot from the drying rack by the sink, and set about boiling some water for mac ‘n cheese.

James remembers the way our mother used to be, back when she still smiled and didn’t take pills or smoke cigarettes all day. He hates our father for what he’s done to her—what he’s still doing to her—because of us. Sometimes I think picking up her prescriptions and leaving cartons of cigarettes outside her door is James’s way of making up for being born.

My father hasn’t always been like this, though. Ask anyone who doesn’t live with us and they’ll tell you he still isn’t. Our house is a shrine to the famous ex-boxer who has it all: a close-knit family, a successful athletic career in a former life, and a solid job at the mill.

It’s amazing how much people overlook when you’re a local celebrity.

Title belts painted an unconvincing shade of gold adorn our living room walls, faded, red boxing gloves dangle from sheetrock nails, and newspaper clippings yellowing in their cheap, tin frames line the fireplace mantle. In the center of it all is an enormous publicity poster from the Armory, the local boxing arena, featuring a man with a crooked nose and a busted lip. He waves triumphantly at our empty living room from atop the crowd’s shoulders.

James “Knockout Jimmy” O’Brien, Granite Fall’s very own boxing legend—a title he held until a young groupie poked holes in the condom she made him wear “for protection.”

My brother was born nine months later, fists already swinging.

I sink into a chair and stare at the pot of water, willing it to boil. Our father only married our mother because he had a public image to maintain—an image that didn’t include an abandoned son that might make him proud someday. Desperate and thinking a second baby would make things better between them, our mother seduced him again, lied about not needing birth control while breastfeeding James, and wound up with me.

Two babies in little more than a year and a half. Knockout Jimmy was forced to give up boxing and take a job in the paper mill.

It broke him, and in turn, he broke us all.

Four

A truck door slams out front. Even before the sound registers, I’m out of the chair, my body tense and ready to run. It’s only 4:09 p.m. He shouldn’t be here. Not yet.

My brother’s faint, familiar whistling keeps me from bolting to my room.

The door to the garage swings open and James breezes in, all dimples and smiles like always, holding one of our father’s beers in his hand. I must look terrified because his grin fades before it can reach his eyes.

“Hey, Sar-bear,” he says softly. “It’s just me.”

I edge over to the stove to check on our water, which has started to boil. My hands are still shaking when I dump the two boxes of macaroni into the pot. “Do you have to drink that crap?”

He doesn’t answer. After a moment, I peek over my shoulder and see him leaning against the counter, arms folded across his chest, eyes narrowed on me. The beer is nowhere in sight.

When James gets serious like this, he looks exactly like Knockout Jimmy in his prime, right down to the bump on the bridge of his nose. Even with sawdust in his blond hair and paper pulp caked onto his coveralls, my brother is gorgeous. Half a dozen girls throw themselves at him whenever we’re in public, but he never dates. I don’t get it. If half a dozen boys threw themselves at me, I’d be out every night. Anything to get out of this house.

“What?” I ask him.

“Nothing. Nice jeans, by the way.”

I roll my eyes, the panic gripping me successfully diffused. James bought me these jeans two weeks ago, one day after I’d drooled over them at the mall on my way home from school. He always does sweet things like that, even when I beg him not to. “To make up for you having to put up with me,” he says, but we both know that’s not what he’s making up for.

He pushes away from the counter, loops an arm around my shoulders, and plants one of the wet kisses I secretly love on my temple.

“Don’t…eww!” Laughing, I sink into his embrace. Wriggling out of his grasp never works. I’m way too light, and he’s way too strong for me to make him do anything he doesn’t want to do. Unfortunately, he knows it. At least he has the decency to grunt when I elbow him in the gut.

“I’m going to get cleaned up,” he says. “Save some of that for me, ‘kay?”

“I always do. Now go away.” I smack him with the hot wooden spoon I’ve been using to stir the macaroni. He yelps and jumps backward. Giving me one last smile, he saunters down the hall.

James is a pain in the ass. I love him more than I love anybody, even when I hear the crack of a beer opening in the bathroom.

As soon as he’s gone, I rush around the kitchen, rounding up the milk and butter and pepper. No one showers and dresses faster than James or I. Maybe it’s because we’ve always had to get in and out of the house as quick as possible. Whatever the case, I like having dinner done before he gets out.

Nineteen-year-old boys shouldn’t be working long hours doing crap jobs in the mill. Especially not ones smart enough to get into just about any college they want. He does it for me, so I do this for him.

Sure enough, before I’ve had the chance to strain the macaroni, he’s out of the bathroom. Our bedroom door slams—he’s always loud—and he cranks his music full blast. Godsmack floods the hallway. I dump half the pot of steaming mac ‘n cheese onto a plate for my father and leave it on the counter where he’ll see it. Maybe he’ll take it as a peace offering and leave me alone tonight.

Armed with bowls of food and Tupperware cups full of tap water, I kick our bedroom door with the toe of my black sneaker. “Are you dressed yet?”

Sharing a tiny bedroom with a teenage boy requires planning and patience. I give James his p

rivacy as often as I can and take pride in the fact that I’ve never walked in on him naked or doing any horrifying boy things. Too bad he isn’t nearly as mindful of my privacy. I can’t begin to count how many times he’s walked in on me changing.

The music shuts off and plunges the house back into a quiet that feels even louder than his music. Canned laughter from whatever sitcom our mother is watching seeps through her closed door down the hall. As soon as he lets me in, I’ll turn on the fan that sits on my nightstand to block out the sound.

James throws open the door wearing only a pair of jeans and a wide grin. The fading yellow bruises on his ribs make me want to throw up, and I nearly spill the water trying to shield my eyes with the bowls. “Do you mind?”

“You are seriously messed up,” he says as I push past him, but I hear the amusement in his voice. “I’ve got pants on. Isn’t that enough?”

No, it’s not. Thankfully, by the time I settle onto my bed with our bowls, he’s pulled on a t-shirt. Covering up is also something James does for my benefit, though he teases me mercilessly about my “skin phobia.” I blame it on a lifetime of hiding bruises and welts under long sleeves and pants, but not all of it. It’s easier to pretend than tell him the real reason I don’t like seeing his body, so I play along. “Maybe if your skin wasn’t DayGlo white, looking at you wouldn’t physically hurt.”

He plops down on the edge of his bed and scowls at me in a way that I think is supposed to be chastising. When I laugh, he gives up, grabs his bowl out of my hands, and shovels pasta into his mouth. We’re a good pair. Neither of us can stay mad at the other for long.

4:26. Nine minutes to go.

My stomach growls, but I only nibble at my food. One bowl of mac ‘n cheese is never enough for James. I want to make sure I have some left to give him when he’s done. To distract myself, I focus on the posters plastered all over the walls on his side of our tiny bedroom—all horror movie and rock music-related, of course. Sometimes I wish he were into sports or supermodels or something a little less morbid. Other than a lone, teal Mariners pennant hanging crooked on the back of our door, his choice in decorations does nothing for my nightmares.