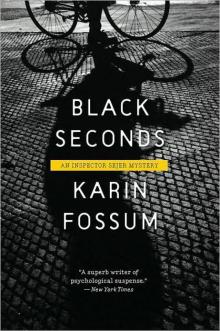

Black Seconds

Karin Fossum

Table of Contents

Title Page

Table of Contents

Copyright

Dedication

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

CHAPTER 18

CHAPTER 19

CHAPTER 20

CHAPTER 21

CHAPTER 22

CHAPTER 23

CHAPTER 24

CHAPTER 25

CHAPTER 26

CHAPTER 27

CHAPTER 28

CHAPTER 29

CHAPTER 30

First Mariner Books edition 2009

Copyright © Karin Fossum 2002

English translation copyright © Charlotte Barslund 2007

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce

selections from this book, write to Permissions,

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company,

6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, Florida 32887-6777.

www.hmhbooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Fossum, Karin, 1954–

[Svarte sekunder. English]

Black seconds/Karin Fossum; translated from

the Norwegian by Charlotte Barslund.—1st ed.

p. cm.

I. Barslund, Charlotte. II. Title.

PT8951.16.O735S8313 2007

839.82'38—dc22 2007036340

ISBN 978-0-15-101527-6

ISBN 978-0-15-603404-3 (pbk)

This is a translation of Svarte Sekunder

First published in English in Great Britain by Harvill Secker

Book design by Jennifer Kelly

Printed in the United States of America

DOC 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Øystein, my younger brother

CHAPTER 1

The days went by so slowly.

Ida Joner held up her hands and counted her fingers. Her birthday was on the tenth of September. And it was only the first today. There were so many things she wanted. Most of all she wanted a pet of her own. Something warm and cuddly that would belong only to her. Ida had a sweet face with large brown eyes. Her body was slender and trim, her hair thick and curly. She was bright and happy. She was just too good to be true. Her mother often thought so, especially whenever Ida left the house and she watched her daughter's back disappear around the corner. Too good to last.

Ida jumped up on her bicycle, her brand-new Nakamura bicycle. She was going out. The living room was a mess: she had been lying on the sofa playing with her plastic figures and several other toys, and it was chaos when she left. At first her absence would create a great void. After a while a strange mood would creep in through the walls and fill the house with a sense of unease. Her mother hated it. But she could not keep her daughter locked up forever, like some caged bird. She waved to Ida and put on a brave face. Lost herself in domestic chores. The humming of the vacuum cleaner would drown out the strange feeling in the room. When her body began to grow hot and sweaty, or started to ache from beating the rugs, it would numb the faint stabbing sensation in her chest which was always triggered by Ida going out.

She glanced out of the window. The bicycle turned left. Ida was going into town. Everything was fine; she was wearing her bicycle helmet. A hard shell that protected her head. Helga thought of it as a type of life insurance. In her pocket she had her zebra-striped purse, which contained thirty kroner about to be spent on the latest issue of Wendy. She usually spent the rest of her money on Bugg chewing gum. The ride down to Laila's Kiosk would take her fifteen minutes. Her mother did the mental arithmetic. Ida would be back home again by 6:40 P.M. Then she factored in the possibility of Ida meeting someone and spending ten minutes chatting. While she waited, she started to clean up. Picked up toys and figures from the sofa. Helga knew that her daughter would hear her words of warning wherever she went. She had planted her own voice of authority firmly in the girl's head and knew that from there it sent out clear and constant instructions. She felt ashamed at this, the kind of shame that overcomes you after an assault, but she did not dare do otherwise. Because it was this very voice that would one day save Ida from danger.

Ida was a well-brought-up girl who would never cross her mother or forget to keep a promise. But now the wall clock in Helga Joner's house was approaching 7:00 P.M., and Ida had still not come home. Helga experienced the first prickling of fear. And later that sinking feeling in the pit of her stomach that made her stand by the window from which she would see Ida appear on her yellow bicycle any second now. The red helmet would gleam in the sun. She would hear the crunch of the tires on the pebbled drive. Perhaps even the ringing of the bell: Hi, I'm home! Followed by a thud on the wall from the handlebars. But Ida did not come.

Helga Joner floated away from everything that was safe and familiar. The floor vanished beneath her feet. Her normally heavy body became weightless; she hovered like a ghost around the rooms. Then with a thump to her chest she came back down. Stopped abruptly and looked around. Why did this feel so familiar? Because she had already, for many years now, been rehearsing this moment in her mind. Because she had always known that this beautiful child was not hers to keep. It was the very realization that she had known this day would come that terrified her. The knowledge that she could predict the future and that she had known this would happen right from the beginning made her head spin. That's why I'm always so scared, Helga thought. I've been terrified every day for nearly ten years, and for good reason. Now it's finally happened. My worst nightmare. Huge, black, and tearing my heart to pieces.

It was 7:15 P.M. when she forced herself to snap out of her apathy and find the number for Laila's Kiosk in the phone book. She tried to keep her voice calm. The telephone rang many times before someone answered. Her phoning and thus revealing her fear made her even more convinced that Ida would turn up any minute now. The ultimate proof that she was an overprotective mother. But Ida was nowhere to be seen, and a woman answered. Helga laughed apologetically because she could hear from the other woman's voice that she was mature and might have children of her own. She would understand.

"My daughter went out on her bicycle to get a copy of Wendy. From your shop. I told her she was to come straight back home and she ought to be here by now, but she isn't. So I'm just calling to check that she did come to your shop and bought what she wanted," said Helga Joner. She looked out of the window as if to shield herself from the reply.

"No," the voice answered. "There was no girl here, not that I remember."

Helga was silent. This was the wrong answer. Ida had to have been there. Why would the woman say no? She demanded another reply. "She's short, with dark hair," she went on stubbornly, "nine years old. She is wearing a blue sweatsuit and a red helmet. Her bicycle's yellow." The bit about the bicycle was left hanging in the air. After all, Ida would not have taken it with her inside the kiosk.

Laila Heggen, the owner of the kiosk, felt anxious and scared of replying. She heard the budding panic in the voice of Ida's mother and did not want to release it in all its horror. So she went through the last few hours in her mind. But even though she wanted to, she could find no little girl there. "Well, so many kids come here," she said. "All day long. But at that time it's usually quiet. Most people eat between five and seven. Then it gets busy again up until ten. That's when I close." She could think of nothing

more to say. Besides, she had two burgers under the grill; they were beginning to burn, and a customer was waiting.

Helga struggled to find the right words. She could not hang up, did not want to sever the link with Ida that this woman embodied. After all, the kiosk was where Ida had been going. Once more she stared out into the road. The cars were few and far between. The afternoon rush was over.

"When she turns up," she tried, "please tell her I'm waiting."

Silence once again. The woman in the kiosk wanted to help, but did not know how. How awful, she thought, having to say no. When she needed a yes.

Helga Joner hung up. A new era had begun. A creeping, unpleasant shift that brought about a change in the light, in the temperature, in the landscape outside. Trees and bushes stood lined up like militant soldiers. Suddenly she noticed how the sky, which had not released rain for weeks, had filled with dark, dense clouds. When had that happened? Her heart was pounding hard and it hurt; she could hear the clock on the wall ticking mechanically. She had always thought of seconds as tiny metallic dots; now they turned into heavy black drops and she felt them fall one by one. She looked at her hands; they were chapped and wrinkled. No longer the hands of a young woman. She had become a mother late in life and had just turned forty-nine. Suddenly her fear turned into anger and she reached for the telephone once more. There was so much she could do: Ida had friends and family in the area. Helga had a sister, Ruth, and her sister had a twelve-year-old daughter, Marion, and an eighteen-year-old son, Tomme, Ida's cousins. Ida's father, who lived on his own, had two brothers in town, Ida's uncles, both of whom were married and had four children in total. They were family. Ida could be with any of them. But they would have called. Helga hesitated. Friends first, she thought. Therese. Or Kjersti, perhaps. Ida also spent time with Richard, a twelve-year-old boy from the neighborhood, who had a horse. She found the contact sheet for her daughter's classmates stuck on the fridge: it listed everyone's name and number. She started at the top, with Kjersti.

"No, sorry, Ida's not here." The other woman's concern, her anxiety and sympathy, which concluded with the reassuring words, "She'll turn up, you know what kids are like," tormented and haunted her.

"Yes," Helga lied. But she did not know. Ida was never late. No one was home at Therese's. She spoke to Richard's father, who told her his son had gone down to the stable. So she waited while he went to look for him. The clock on the wall mocked her, its constant ticking: she hated it. Richard's father came back. His son was alone in the stable. Helga hung up and rested for a while. Her eyes were drawn to the window as if it were a powerful magnet. She called her sister and crumbled a little when she heard her voice. Could not stand upright any longer, her body was beginning to fail her, paralysis was setting in.

"Get in your car straight away," Ruth said. "Get yourself over here and together we'll drive around and look for her. We'll find her, you'll see!"

"I know we will," Helga said. "But Ida doesn't have a key. What if she comes back while we're out looking for her?"

"Leave the door open. It'll be fine, don't you worry. She's probably been distracted by something. A fire or a car crash. And she's lost track of time."

Helga tore open the door to the garage. Her sister's voice had calmed her down. A fire, she thought. Of course. Ida is staring at the flames, her cheeks are flushed, the firemen are exciting and appealing in their black uniforms and yellow helmets, she is rooted to the spot, she is bewitched by the sirens and the screaming and the crackling of the flames. If there really were a fire, I, too, would be standing there mesmerized by the shimmering heat. And besides, everything around here is like a tinderbox, it hasn't rained for ages. Or a car crash. She fumbled with her keys while she conjured up the scene. Images of twisted metal, ambulances, resuscitation efforts and spattered blood rushed through her mind. No wonder Ida had lost track of time!

Distracted, she drove to her sister's house in Madseberget. It took four minutes. She scanned the sides of the road the whole time; Ida was likely to appear without warning, cycling on the right-hand side as she should, carefree, safe, and sound. But she did not see her. Still, taking action felt better. Helga had to change gears, steer, and brake; her body was occupied. If fate wanted to hurt her, she would fight back. Fight this looming monster tooth and nail.

Ruth was home alone. Her son, Tom Erik, whom everyone called Tomme, had just passed his driving test. He had scrimped and scraped together enough money to buy an old Opel.

"He practically lives in it," Ruth sighed. "I hope to God he takes care when he drives. Marion has gone to the library. They close at eight, so she'll be home soon, but she'll be fine on her own. Sverre is away on business. That man's never here, I tell you." She had her back to Helga and was struggling to put on her coat as she spoke the last sentence. Her smile was in place when she turned around.

"Come on, Helga, let's go."

Ruth was a slimmer and taller version of her sister. Five years younger and of a more cheerful disposition. They were very close, and it had always been Ruth who had looked out for Helga. Even when she was five, she was looking out for ten-year-old Helga. Helga was chunky, slow, and shy. Ruth was lively, confident, and capable. Always knew what to do. Now she took charge of her older sister once again. She managed to suppress her own fears by comforting Helga. She reversed the Volvo out of the garage and Helga got in. First they went to Laila's Kiosk and spoke briefly to the owner. They had a look around outside. They were searching for clues that Ida had been there, even though Laila Heggen said she had not. Then they went into the center of Glassverket. They wandered round the square scanning the passing faces and bodies, but no sign of Ida. Just to be sure, they went past the school where Ida was a Year Five pupil, but the playground lay deserted. Three times during the trip Helga borrowed Ruth's cell phone to call her home number. Perhaps Ida was waiting in the living room. But there was no reply. The nightmare was growing; it was lying in wait somewhere, quivering, gathering strength. Soon it would rise and crash over them like a wave. It would drown out everything. Helga could feel it in her body: a war was being fought inside her; her circulation, her heartbeat, her breathing, everything was violently disturbed.

"Perhaps she's had a flat tire," Ruth said, "and had to ask someone to help her. Perhaps someone is trying to fix her bike right now."

Helga nodded fiercely. She had not considered this possibility. She felt incredibly relieved. There were so many explanations, so many possibilities, and hardly any of them scary; she had just been unable to see them. She sat rigidly in her seat next to her sister, hoping that Ida's bicycle really had had a flat. This would explain everything. Then she was gripped by panic, terrified by this very image. A little girl with brown eyes might make a driver stop. Under the pretext of wanting to help her! Pretending! Once again her heart ached. Besides, if Ida had had a flat, they would have spotted her; after all, they were on the very route Ida would have taken. There were no shortcuts.

Helga stared straight ahead. She didn't want to turn her head to the left, because that way lay the river, swift and dark. She wanted to proceed as quickly as possible to the moment when everything would be all right again.

They drove back to the house. There was nothing else they could do. The only sound was the humming of the engine in Ruth's Volvo. She had turned off the radio. It was inappropriate to listen to music when Ida was missing. There was still a bit of traffic. Then they spotted a strange vehicle. They saw it from a distance; at first it looked unfamiliar. The vehicle was part motorcycle, part small truck. It had three wheels, motorcycle handlebars, and behind the seat was a drop-sided body the size of a small trailer. Both the motorcycle and the truck body were painted green. The driver was going very slowly, but they could tell from his bearing that he had sensed the car, that he knew they were approaching. He pulled over to the right to let them pass. His eyes were fixed on the road.

"That's Emil Johannes," Ruth said. "He's always out and about. Why don't we ask him?"

> "He doesn't talk," Helga objected.

"That's just a rumor," Ruth said. "I'm sure he can talk. When he wants to."

"Why do you think that?" Helga said doubtfully.

"Because that's what people around here say. That he just doesn't want to."

Helga could not imagine why someone would want to stop talking of his own free will. She had never heard of anything like it. The man on the large three-wheeler was in his fifties. He was wearing an old-fashioned leather cap with earflaps, and a jacket. It was not zipped up. It flapped behind him in the wind. As he became aware of the car pulling up alongside him, he started to wobble. He gave them a hostile look, but Ruth refused to be put off. She waved her arms at him and gestured that he should stop. He did so reluctantly. But he did not look at them. He just waited, still staring straight ahead, his hands clasping the handlebars tightly, the flaps of his cap hanging like dog ears down his cheeks. Ruth lowered the car window.

"We're looking for a girl!" she called out.

The man made a face. He did not understand why she was shouting like that. There was nothing wrong with his hearing.

"A dark-haired girl, she's nine. She rides a yellow bike. You're always on the road. Have you seen her?"

The man stared down at the asphalt. His face was partly hidden by his cap. Helga Joner stared at the trailer. It was covered by a black tarpaulin. She thought she could see something lying underneath. Her thoughts went off in all directions. There was room for both a girl and a bicycle underneath that tarpaulin. Did he look guilty? Then again, she knew that he always wore this remote expression. Sometimes she would see him in the local shop. He lived in a world of his own.

The thought that Ida might be lying under the black tarpaulin struck her as absurd. I'm really starting to lose it, she thought.

"Have you seen her?" Ruth repeated. She had a firm voice, Helga thought. So commanding. It made people sit up and take notice.

Finally he returned her gaze, but only for a moment. His eyes were round and gray. Had he blinked quickly? Helga bit her lip. But that was the way he was; she knew he didn't want to talk to people or look at them. It meant nothing. His voice sounded somewhat gruff as he replied.