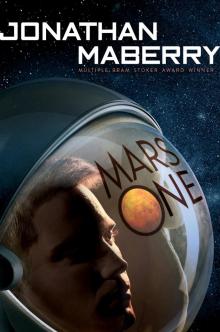

Mars One

Jonathan Maberry

This is for Neil Armstrong. On July 20, 1969, I was an eleven-year-old kid sitting in front of a flickering black-and-white TV, watching the impossible happen as you stepped out of the lunar module to put a human footprint on another world.

It was one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.

And, as always, for Sara Jo.

Acknowledgments

Space travel happens in a vacuum. Writing does not. I’ve been unusually fortunate to have as advisers some of the world’s more notable astronomers, medical doctors, astrophysicists, and space technologists. When I get the science right, cheer them. When I get it wrong, yell at me.

My heartfelt thanks go to Dominick D’Aunno, physician adviser to NASA; the good folks at the Johnson Space Center in Houston; Brother Guy Consolmagno, SJ, president of the Vatican Observatory Foundation; and Lisa Will, professor of physics and astronomy at San Diego City College.

PART ONE

BLUE MARBLE

Astronomy compels the soul to look upward and leads us from this world to another.

—Plato, Republic

Chapter 1

* * *

She said, “You’re going to die up there.”

“You’re going to die down here,” I said.

We sat there, holding hands, trying not to cry. Failing like we always do.

I said, “Izzy . . . I’m going to Mars.”

“Mars doesn’t want you,” she said. “I do.”

Chapter 2

* * *

My name is Tristan Hart.

When I was ten my parents told me that we were going to Mars. Not Mars, California, or Mars, Pennsylvania, or even Mars, Texas—which is a ghost town we visited once.

No . . . actual Mars. The planet. Millions and millions of miles away from Earth.

That Mars.

I believed them too, because ten-year-old kids believe pretty much everything their parents tell them. I was still pretty sure Santa Claus was real. Or real-ish. So Mars? Sure, why not?

Then I was sixteen. I didn’t believe in Santa anymore. Or the Easter Bunny or much of anything.

But I believed we were going to Mars.

The Mars One, an independent international space program, sent a bunch of robots up first and tons of supplies. People were next. Originally it was going to be four people, but they got tons of extra funding from reality-show producers all over the world and now there were forty of us going. The first wave, they called it. Colonists.

It was a one-way trip. No one was coming back. They’d send other colonists every two years. If . . .

If we make it.

If we didn’t die.

If we could make it work.

If we became Martians.

I was sixteen. I’d turn seventeen in outer space.

If I lived long enough I’d celebrate my eighteenth birthday on another world.

Mars, man.

We were going to Mars.

And no matter what happened, we were never coming back here.

Never.

Ever.

Chapter 3

* * *

I still went to high school. The people running the Mars One project sent us back to school for six months before we were to leave. Parts of each month, anyway. We had to go for long training weekends, but most of that time we were back in school. Me to my hometown school in Madison, the other three to schools in their countries. They want all four of the teens who are going to be “habituated to age-appropriate social behavior enforced by peer interaction.” Which is their way of saying they want us to be normal.

Or, the way my friend Herc put it, “They don’t want to be stuck in a tin can with freaks.”

“Pretty much,” I agreed.

“Way too late for that.”

I sighed. We tapped pop bottles. Sipped. Watched the clouds sail slowly across the Wisconsin sky. We were sprawled on bleachers on the north side of the track outside of our school, James Madison Memorial High. It was September 10 but it felt like mid-July because of a freak heat wave that turned everything into a sauna. Humidity and temperature in the eighties. Forget anything that involved moving.

Sweating was a theme. The only easy thing to do was talk.

“And this is really happening?” asked Herc.

“Yeah.”

“Going to Mars.”

“Yeah.”

He shook his head, grinned, and took a long swallow.

“Oh, please,” I said, “if you’re going to give me the same old ‘you’re going to die up there’ speech, save it. I’m tired of—”

“Nah,” Herc said. “Even I’m tired of hearing that crap and I’m staying here.”

“Okay.”

“I’m just wondering what you’re going to do about them?” He used his bottle to point to the crowd on the other side of the chain-link fence, behind the cops and their wooden sawhorse barricades. The sunlight flashed on hundreds of cameras—cell phone and professional. Broadcast towers rose above the seven news vans parked on the street. There was a bunch of protestors, too. There always were, ever since Mars One started. Some were just whack jobs who seemed to like to yell at anyone who was doing something interesting. Some were people who wanted to try and get onto the news, even if it was via a photobomb. Some, though, were religious nuts who seemed to think going to Mars was somehow against God. Not sure how that worked, though. Those protestors were always there.

What I was looking for were the really scary ones, the ones who always wore white robes and red bandannas, the ones who called themselves the Neo-Luddites. Those guys were freaky, but I knew they wouldn’t be on school grounds. The Neo-Luddites usually only showed up at official mission events or sometimes when we were filming an episode for one of the reality shows.

The Neo-Luddites were a deeply weird kind of extremist group. Not exactly religious—I mean, they weren’t fundamentalists the way you’d think. It’s hard to explain them because they mostly talked about what they didn’t believe in and what they were afraid of, but not really much at all about what they did believe in.

As far as I could tell there were two kinds of them. Most of their group wasn’t violent. They were organized and persistent but they didn’t cause a ruckus at events. But there was a smaller bunch that was way dangerous. No one in the press or military or in Mars One could seem to decide it they were an official part of the Neo-Luddites or a separate splinter group who just used that name. But that bunch didn’t just stand around and wave signs. They sent an actual hit team out to place magnetic limpet mines on the hull of one of the SpaceX sea-launch stations. The bombs had some kind of special trembler switch that was triggered by the exhaust blast when the SpaceX team test-fired one of the new Falcon Heavy rockets. Seventeen people were killed—blown to bits—and another thirty were hurt, some really bad. The four-person Neo-Luddite team was killed too. No one can tell if it was a suicide attack or if they got caught in their own blast by accident. Dead either way. The authorities used DNA from some of the body parts they fished out of the water to identify one man who was known to have ties to the Neo-Luddites, and when accusations were made the Neo-Luddite goofballs didn’t deny it. They didn’t admit it either. What they did was post photos of the murdered SpaceX people on their website with the heading: “BETRAY THE TRUST—PAY THE PRICE!”

The Trust . . . ? They never came right out and said what that meant. Everyone on the news had been beating each other up with theories.

That was the first attack. After that the Neo-Luddites were tied to some other bombings—of a parts manufacturer making equipment for Virgin Galactic, an electronics firm building a guidance system for SpaceDev, a metallurgy plant making hull sections under contract to ARCA Space Corporation, and the chemical processing plant in China that m

akes fuel for the Shenzhou program. More people were killed, and every program upped its security game by a factor of ten. Definitely Mars One did. The mission shrinks grilled every single candidate six ways from Sunday. Lie detector tests, wave after wave of psych evals, questioning by cops from Interpol. It was scary as hell. All through it I felt sweaty and guilty for no reason. If they’d leaned any harder on me I’d have confessed to everything up to and including the assassination of Abraham Lincoln.

There was a movement going around to have the Neo-Luddites declared an actual terrorist group. Some of them definitely were, which was why I always looked to see if there were any in the crowd wherever I went. I’d seen them a bunch of times, but always the quiet ones. None of them had chucked a bomb at me, so I’m putting that in the win category.

Scared me, though. What if they went after my folks? Or Izzy?

I wasn’t the only person losing sleep over it. I just wished it made some kind of sense.

Today, though, it was the usual suspects. Nobody to be scared of.

The sun baked us all. I sighed and rested the cold bottom of the pop bottle on my forehead.

When I didn’t say anything, Herc snorted and sat up. He was about my size: five ten, lean, built for running. We both ran track. I was faster, but he could run all day. He wore cargo shorts and a T-shirt from the church a cappella choir he was in, the Preach Boys. “They’re going to dog you every day until you light the candle, you know that, right?”

“They’ve been dogging all of us since the mission administrators at Mars One announced the final team three years ago,” I said.

“Yeah, but you and the other kids are the real story.”

“How do you figure that?”

“C’mon, everyone else is an adult. They’re legal, which means they can vote, get married, whatever. They have a choice. You guys are minors. You’re going because your families are going. A lot of people think that’s messed up.”

I pulled my shades down to look at him over the lenses. Herc’s family emigrated from Mexico two years before he was born, and he had dark brown hair and his skin was a medium tan. I was eighth-generation American white boy, but I took a tan that made me darker than him. A lot of it earned when our Mars One training teams were in the Bahamas doing underwater drills in space suits.

“You think it’s messed up too?”

He shrugged. “You want me to lie or do you want to hear what I really think?”

“You always tell me what you really think. So . . . sure, fire away.”

Herc took a few moments with that, glancing at the reporters and gawkers, then back to me, then up at the sky. “I wish I was going too,” he said.

I waited for the grin, the punch line. But his face didn’t change.

“You serious?” I asked.

“God’s honest truth, Tris.”

The buzzer rang. Lunch was over. I did a slow sit-up and swung my legs off the bleacher.

“You’re crazier than I am,” I told him.

“You asked.”

A dragonfly buzzed around me and then whizzed off.

“Saw your mom on the news,” Herc said. “She looked pissed.”

“Mom always looks pissed.”

“Nah, your mom’s cool. She’s just intense.”

“I guess.”

The news story last night was about the series of technical problems they’d had with one of the rockets. Technically they weren’t our rockets—Mars One was leasing them from SpaceX—but my mom was the chief mission engineer, so it was her job to make sure everything was totally up to code. She didn’t allow for mistakes. She didn’t even allow for “margin of error.” As she’d said a million times, “In space you get one try to do it right or you’re dead.” Herc was right; she was intense. She was also almost always right.

“That guy from CNN was riding her pretty hard,” said Herc. “All that stuff about sabotage and stuff.”

“Not happening.” I yawned and stretched. “We have better security than NASA. I’m serious.”

“Yeah, maybe,” said Herc, “but people are saying that someone’s trying to stop you guys from flying.”

“People are always saying that.”

He shrugged. “Whatever, dude. You’re the one who’s going to be sitting on a big tank of highly flammable rocket fuel, not me. If you blow up, can I have your Xbox?”

“Don’t take this the wrong way, man, but bite me.”

“Yeah, yeah.”

We stood up. So did the two private security guys who were assigned to me. My dad called them Frick and Frack. Their real names were Kang and Carrieri, but I called them that only when I had to. They were here to protect me and they’d apparently had their personalities surgically removed along with any trace of a sense of humor. On any given day they’d say about ten words to me.

In a strange little pack, we walked off the field and back toward the school. Even from that distance I could hear all those cameras going click-click-click.

Chapter 4

* * *

I didn’t really want to go inside because it was the Wednesday Powwow, which was the insanely corny and culturally insensitive 1950s name they still used for the weekly assembly at Madison High. I mean, really?

The big problem was that I was the afternoon assembly. Or the star of it, anyway. Since I’d come back to school from underwater training, the principal had approached the Mars One directors and my folks to get permission for me to talk to the other kids. Everyone thought it was a great idea. Terrific PR, a learning experience, blah-blah-blah.

I wasn’t crazy about being the center of attention. I wasn’t exactly shy, but my ego still fit into the box it came in. Even being part of this mission hadn’t made it swell. The mission shrink said I was “remarkably well balanced.” If she only knew the stuff that really went on inside my skull I’d get kicked off the trip.

Which Izzy would love.

But I had a great game face. I looked like Joe Middle-America. A healthy, reasonably intelligent, reasonably sane, reasonably okay-looking, reasonably talented sixteen-year-old who some media fruitcake decided should be the “face” of Mars One.

Me.

I mean, it was nuts. There were better-looking people going. Even the other teenage guy, Luther, was hotter than me—or so Izzy’s friends kept saying—and both of the teen girls, Zoé and Nirti, were smarter. Actually Zoé was freakishly smart, so maybe she didn’t fit into the equation.

Herc and I both knew why I was picked, though, and it had nothing to do with me being the average guy on the mission—or the Everybody, as our mission PR guy kept saying. It wasn’t that.

It was because of Izzy.

Because of Izzy and me.

We’d been in love since we were twelve. If I weren’t going, then you could bet cash money we’d end up married. Our chemistry was perfect. People saw us together and they started to smile, even if they were having a bad day. Maybe we glowed, I don’t know.

We tried to keep our relationship on the DL because it was hard enough between us knowing that there was a sell-by date on what we had. But it got out, because no matter how smart we tried to be with our social media we weren’t sly enough. Our bad. Now we were the star-crossed lovers. Paint that in big letters across the sky. That phrase, in one form or another, had been on every news feed, print magazine, cable show, and meme since the story broke.

I was the handsome hero who was going off to conquer a new world.

Izzy was the tragic heroine left behind with a broken heart.

I’m not joking, the media people put it like that. Actually they made it sound even worse than that. There was even an e-book out called The Girl He Left Behind. Completely unauthorized, but it had pictures of both of us and all sorts of wild stuff about how this was the greatest love story of the twenty-first century. We got offers from forty different producers to do reality shows, and after telling each other we would never in a million years do something like that, we caved. They put a whol

e bunch of zeroes on those offers. Izzy would be set for life, and I’d actually be able to donate a big chunk to the Mars One project.

Making tough and complicated decisions like that was part of why the principal and teachers at my school wanted me to talk to the kids in the Powwow. To try and stop the rumor mill from grinding us all down. Like that was going to work.

The other reason was better.

They wanted me to cut through the crap that was all over the Internet about what we were doing and why. The mission PR people put together a 3-D presentation for me with all the right talking points. I agreed as long as the whole thing wasn’t about Izzy and me.

She promised me it wouldn’t be. Her smile looked like molded plastic when she said that, though.

“Why are you making that face?” asked Herc as we approached the door.

“What face? I’m not making a face.”

“Yeah,” he said, “you are.”

“What kind of face?” I demanded.

“Like you haven’t taken a good dump in two months.” He clapped me hard on the shoulder. “You got to lighten up, Tris, or you’re going to explode long before you crash-land on Mars.”

He was laughing as we went inside the building.

I wasn’t.

And for the record, I don’t make faces. He was way wrong about that.

Chapter 5

* * *

The assembly room was packed. Pretty sure every kid at Madison was there; all the teachers, too. The place was crammed with people in every seat, others standing in the aisles. Somewhere a fire marshal was having a meltdown.

Frick and Frack made a path for me through the crowd—sometimes using manners, sometimes glaring nuclear death at people until they got out of the way. They escorted me to the stage, where the principal and all of my teachers waited. The teachers stood in a line to shake my hand, which felt weird. The adults all took the mic to talk about me as if I were someone else, telling the kids I grew up with how special I was, how brave, all that stuff. I stood there and could feel my face grow red-hot. By the time my science teacher got finished talking I wanted to crawl off the stage and hide in the boys’ room. I’m not going to call him a liar, but the version of Tristan Hart he was hyping sounded like a cross between Captain America and Stephen Hawking.