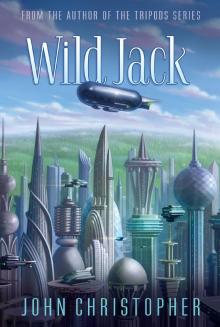

Wild Jack

John Christopher

THANKS

FOR DOWNLOADING THIS EBOOK!

We have SO many more books for kids in the in-beTWEEN age that we’d love to share with you! Sign up for our IN THE MIDDLE books newsletter and you’ll receive news about other great books, exclusive excerpts, games, author interviews, and more!

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com/middle

To Wild Julia

1

I WOKE UP TO THE sound of humming, like that of an enormous bee whose wings you might think filled the sky. I did not need to look at my watch to know it was eight o’clock. Today was Wednesday, and that was the Rome airship coming in to land.

Yawning, I stretched but did not get up right away. The windows facing my bed took up the full length of the wall, and I could lie and look out over the parks and buildings of London. In the foreground was the garden of our house, extending for more than a hundred yards in patterns of lawn and shrubbery, flower beds, and cunningly designed streams and pools. The gardeners were already at work.

Beyond, divided from the garden by a high fence covered with climbing roses, lay St. James’s Park, at this time quiet and empty. In the distance I could just see a corner of the Palace, which was the seat of government for the city. My father was a member of the council, which met there, though at the moment he and my mother were away, on holiday in the Mediterranean.

In the opposite direction stood the huge funnel shape of the airport. The humming grew louder as the airship descended toward it, then cut off as it sank beneath the containing walls. I should not have heard it at all, of course, if my windows had not been opened—my room was sound-proofed and air-conditioned—but I rather liked the noise. I also liked waking to the smell of growing things, new-mown grass and flowers. The air-conditioner had a scent console incorporated in it which could have provided much the same effect, but I never thought it got things quite right.

The day was fine. Sunlight lit the scene outside and slanted through my windows, sharpening the blues and reds of the Persian carpet beside my bed. That was enough in itself to justify feeling cheerful, but I was aware of a sense of anticipation as well. I remembered: Miranda.

She was a cousin of mine, or, to be accurate, her father and mine were cousins. The Sherrins lived in Southampton, seventy miles from London. They had lived in London some years earlier, and Mr. Sherrin and my father had been political rivals. I knew nothing about the causes of their disagreement, but it had been serious. There had apparently been a lot of argument and debate, with people taking sides. In the end it had come to an issue in the council, where my father had won. To clinch matters, Mr. Sherrin’s opponents had voted him into exile.

My father had not wanted that and in the years since then had worked to have the order of banishment revoked. He had succeeded a few months earlier. The Sherrins had not yet decided whether or not to return permanently to London, but my parents had suggested that they make use of our house while they themselves were away on holiday. So they had come up from Southampton and brought Miranda with them.

She was a few months younger than I, and I remembered her as a thin plain girl with not a great deal to say for herself. I discovered she had changed a lot. She still did not talk much, though what she did say was in a cool low voice that made you want to listen. In other respects she was very different. Her hair was longer, silky, and more golden than I remembered, and her face was fuller, but with attractive hollows under high cheekbones. There was her smile, too, which was harder to describe: slow and strange. It was rare, but worth waiting for.

I decided to get up and pressed the button by my bed which would flash a call signal in the servants’ quarters. It was very quiet now that the airship had landed, with only the small distant sounds of the gardeners. I wondered how many people had come from Rome: not many, probably. People did not travel much between the cities. Why should they, since one place was so much like another? There was no reason to leave one’s home city except to go on holiday, and no one was likely to want to go on holiday to another city.

The bell on my door pinged softly and I called, “Come in.” My manservant, Bobby, crossed the room to my bed.

“Good morning, young sir. I trust you slept well. What would you like for breakfast today?”

He listened and nodded as I gave my orders, then went to run my bath and put out my clothes to wear, asking me which shirt I preferred. Before leaving to fetch my breakfast, he said, “Is there anything else, young sir?”

I shook my head. “No, boy!”

Bobby had been my manservant since I came out of the nursery. He was more than three times my age.

• • •

White clouds drifted in from the west but the morning stayed bright, and after breakfast I took Miranda down to the river. Our boathouse on the Thames was close to the Houses of Parliament, which had once been the center of government but was now a museum. It was not much visited: I saw servant-attendants there, but no one else.

We met Gary at the boathouse. He and I were in the same class at school and slept in the same dormitory. We were friends after a fashion, though we did seem to spend a lot of time fighting. Usually I won. We were about the same height, but he was thinner than I was and less strong.

“You’re late,” he said.

That was true; Miranda had taken a long time getting ready. I paid no attention to him and led the way into the boathouse.

There were four boats in the slips. One was the family cabin cruiser, another was my father’s speedboat, and a third belonged to my mother. The fourth was mine, a present for my last birthday. According to the regulations, I was not old enough to take a powerboat out on the river, but my father had managed to fix things for me.

It was an eight-foot dinghy, bright red, with a small but quite powerful motor. The boathouse servant made it ready, unplugging the powerline through which the batteries had been charged and connecting the batteries to the engine. He saluted me and handed over.

She was called “Sea Witch.” I was not entirely satisfied with the name and thought occasionally of changing it. In the last day or two it had crossed my mind that “Miranda” might be a good name for a boat.

I eased her from the slip into the channel and so out of the boathouse into the river. With Miranda and Gary standing on either side of me, I opened up the throttle and took her down river. There were quite a lot of small craft about. Over the high-pitched hum of the engine I asked Miranda about Southampton: did people there do much boating?

She shook her head, the wind tumbling her yellow hair. “Not as much as here. Of course, there’s much less river within the wall. The Outlands are nearer to us than they are to you.”

“The Outlands” was the name for everything outside the boundaries of the cities and the holiday islands. There were roads running through them linking the civilized places, and the ground was kept clear for fifty yards or so on either side of the roads. Beyond that, nature ran riot, chiefly in forest.

Savages lived in the Outlands. They occasionally tried to attack cars on the roads, but usually without success since the cars traveled too fast to be damaged by a stone or two thrown by a few barbarians. If they attempted to mass in large numbers or put up barriers or obstacles, electronic monitors gave a warning to the nearest control unit. It was easy enough then to send an airship to deal with them.

But here we were in the heart of London, one of the biggest cities in the world, and the Outlands seemed very remote. On either bank of the Thames we saw buildings spaced among patches of green. I recalled a picture I had seen of Old London, with the houses packed close together, row on row of them, close-cr

ammed and full of people—millions of people swarming like ants. Today we numbered ourselves in a few thousand. I tried to think about a million people—a thousand times a thousand—but it was beyond imagining.

In the distance, across open ground, I could see our house and even make out the small turret room which was my father’s study. To the right was the airport funnel, with an airship at this moment rising out of it. That one was starting on the long route to Delhi. I knew the times of all the scheduled flights.

The energy tower stood farther to the right still, a slender shaft rising high into the sky. It was clad in anodized aluminum which reflected the sun so that it gleamed like a tower of gold—which in a way it was, because the energy tower generated and dispensed the power which kept the city alive. Everything depended on it: this small boat as much as the automat factories. The power line in the boat house ran back to the energy tower.

Airships had their own nuclear motors, but everything else came from the towers. The cars which traveled between the cities were powered by fuel cells which had to be charged at regular intervals. Each city had its own energy tower, but the London tower was the biggest in England.

I drove the boat between two pillars, the remains of an old bridge, and we came out into the wider stretch of the London docks. They had no use any longer; air freighters carried what trade there was in and out of the city.

It must have been a strange place in the old days, with the great ships rising high above the water, the air loud with the cries of stevedores, the clank of steel, the hoarse shrieks of steam whistles. We traveled now through silence and emptiness. I saw a solitary speedboat in the distance, that was all. Not many people came to this section of the river, disliking it for the bare wideness of its waters.

Gary held the same view and said so. This was boring. Why didn’t we go to the pleasure gardens on the south bank? There would be something to do there.

I asked Miranda: “What do you think? Would you rather go to the pleasure gardens?”

She shook her head slightly. “I like it here.”

I took the boat under high walls of gray stone, hiding the sun. We came to a flight of worn steps, and I tied up to a rusting metal ring. I helped Miranda out, and Gary and I followed her up the steps to the top. We came into sunshine again and sprawled on the warm stone, Gary and I carelessly and Miranda neatly. She was wearing lime-green trousers with a primrose-yellow blouse, and she hugged her knees with clasped hands.

I said: “I came here once on my own and stayed till after dark. It was a bit weird: the gray of the sky and the river getting darker all the time and no sound apart from the lap of waves and a seagull. I could almost imagine I saw a ghost liner coming in from the estuary.”

“Some imagination.” Gary laughed. “What a nut!”

Miranda said quietly, “I can understand that. It’s a strange atmosphere, even in daylight.” She smiled. “I don’t think I would have had the nerve to stay here alone after dark.”

“Two nut cases,” Gary said. But he sounded more resentful than contemptuous.

• • •

Mr. Sherrin appeared in the sitting room while I was waiting for Miranda that evening, and I put down the magazine I had been glancing through. He said, “That’s all right, Clive. Don’t let me interrupt you.”

I shook my head. “I wasn’t reading. Just passing the time.”

The magazine was called Twent-Cent and carried stories and picture strips about the past, before the Breakdown. They were mostly lurid accounts of violence and crime, and at one time I had been keen on them. But one felt differently as one grew older; they were really meant for a younger age group than mine. I was a little ashamed of being found looking at the magazine at all.

Mr. Sherrin smiled. “Waiting for Miranda? You’ll need plenty to occupy your time if you’re going to make a habit of that.”

He was tall and gray-haired, with a face that, except for being thinner, resembled my father’s: both had bushy eyebrows and rather long noses. But there was also a difference in expression, which I suppose you might sum up by saying that my father was a laughing man, Mr. Sherrin a smiling one. His smile was quiet and humorous, seeming to indicate someone who took a cool look at people and situations and the world in general. It was a bit like Miranda’s, when I came to think of it.

My father’s laughter, on the other hand, appeared to stem from a greater energy and boisterousness. Quietness was characteristic of Mr. Sherrin, but my father was most himself in doing something or saying something—the latter generally loudly and to an accompaniment of expansive gestures. I had occasionally found this trying. It was not that I was ashamed of my father—I was very proud of him—but there had been moments when I wished he could go about things a little less noisily.

I made some fumbling reply to the remark about Miranda, and Mr. Sherrin said, “Where are you off to this evening, anyway? The theater?”

I shook my head. “Only a party.”

“Anyone I know?” He smiled again. “I’m a bit out of touch with London society, of course.”

The drily humorous comment was, I thought, typical of him.

I said, “Brian Grantham. His parents are away as well—in the Hebrides, I think.”

“Michael Grantham would be his father?” I nodded. “Yes, I remember him.”

He was silent after that. I wondered if Brian’s father had also been mixed up in the events leading up to the banishment—and one of those, perhaps, who had wanted the ban continued. But it wasn’t something I could ask questions about.

Miranda appeared at last and we could go. Mr. Sherrin put music on as we left—Mozart or something similar. In my father’s case it would have been Tchaikovsky or more likely Gilbert & Sullivan. He had an infuriating habit of whistling Sullivan tunes off-key.

• • •

We took a taxi—open, because it was a clear warm evening—to the Granthams’ house, which was also on the north bank but farther west—not far from the wall, in fact. Brian, who had asked us, was at the same school as Gary and I, but a couple of years older. He had never invited either of us before, and I was fairly sure I knew why he had done so this time. The reason sat beside me, looking beautiful in a crimson dress.

A dozen or more were there already, boys and girls of Brian’s age. There was the usual food and drink, dancing, and chatter. We were outside in the garden, and as the evening darkened, colored lamps lit up in the branches of trees all round. Occasionally there was also the light of a passing boat on the river. Music came from a number of speakers, and in quiet passages one could hear the splash of water.

We were drinking a light sparkling wine, and supplies ran out. A servant who looked about seventy came shuffling out with more. Someone called, “Get a move on, boy! We don’t want to have to wait all night.”

“Beg pardon, young sir.”

He attempted to open a bottle with uncertain fingers, but the one who had spoken, Martin, said, “Leave it, boy, and totter away. I’ll see to it.”

The servant retreated, with another mumbled apology, and Martin started opening the bottle.

When the servant was out of earshot, Brian said, “Was that necessary?”

His voice was low but angry. Martin looked at him.

“What?”

“Talking that way to him. It’s not his fault if he’s old.”

Martin laughed. “Perhaps not. Your parents’ fault having him around, maybe. What’s wrong with the rest home?”

The rest home was for old and sick servants, a kind of hospital. Food and shelter were provided, but not much in the way of extra comforts. There were usually plenty of vacancies; the servants who went there tended not to live very long.

“If you don’t know,” Brian said, “I don’t suppose I could tell you.” I was surprised how angry he was. “Anyway, he’s our servant and I’ll tell him what to do

. And I don’t like hearing him called ‘boy.’”

Martin stared at him. “What’s got into you? They’re always called ‘boy.’”

“Then it’s about time they weren’t. They’re human beings, like us.”

“Like us? Sure. Maybe we should fetch and carry for them, turn about. And have one or two of them on the council.”

There was some laughter.

Brian said, “It might not be a bad idea, at that. What right do we have to make them serve us?”

The laughter stopped; I imagine the others were as shocked as I was. The division between masters and servants was something we had taken for granted all our lives—something you did not even need to think about. Nor want to. A remark like that gave one an uncomfortable, crawly feeling. Brian had probably drunk too much wine, but that didn’t justify it. Martin merely turned away, and no one else said anything. We all wanted to drop the subject, but Brian insisted on going on.

“Have you ever thought about how they came to be servants in the first place?”

Martin turned back and looked at him in exasperation. He said dismissively, “What needs thinking about? Because they’re descendants of savages, that’s why. They wanted to come into the cities to get away from the Outlands, and our ancestors let them. In the Outlands they would be just about scraping a miserable living if they weren’t killed by wild beasts first. With us they have food and clothing and shelter. They made the bargain.”

“Their great-grandfathers made the bargain,” Brian said. “Does that bind them?”

The question was too absurd to need an answer.

Brian went on, “And what about the time before that—before there were savages at all?”

“They’ve always been savages.”

“No, they haven’t. Only since the Breakdown.”

Martin shrugged. Before the Breakdown were the Dark Ages—millennia of squalid barbarism, followed by the two centuries of the technological explosion which were as bad if not worse. We all knew that. For two hundred years mankind, suddenly given machines and power, had squandered the resources of energy, burning up coal and oil recklessly, with no thought for the future. Then the oil supplies had failed and the coal seams had become too thin for economic working. As a result the complex structure of the early twenty-first century had fallen apart in wars and rebellions and men fighting for crusts of bread among rusting machines.