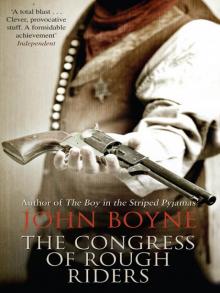

The Congress of Rough Riders

John Boyne

About the Book

William Cody grows up surrounded by his father’s tales of Buffalo Bill, to whom he is distantly related, and his fantasies of the Wild West.

Though he escapes his heritage by fleeing abroad and starting a new life for himself, he finds that he is always drawn back to England and to his ancestry.

When his father proposes that together they should recreate Buffalo Bill’s stage show, ‘The Congress of Rough Riders of the World’ for a contemporary audience, William refuses to have any part of it. When tragedy strikes, however, it is to his father that he must eventually return.

Contents

Cover

About the Book

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter One: On Lookout Mountain

Chapter Two: A Society of Men

Chapter Three: Separation

Chapter Four: East and West

Chapter Five: Rome, London, Tokyo

Chapter Six: Reacquaintance

Chapter Seven: Celebrity

Chapter Eight: Scouts of the Plains

Chapter Nine: Reunions

Chapter Ten: The New American Way

Chapter Eleven: A Perfect Stranger

Chapter Twelve: Last Days

About the Author

Also by John Boyne

Copyright

THE CONGRESS OF

ROUGH RIDERS

John Boyne

For Carol, Paul, Sinéad and Rory

Chapter One

On Lookout Mountain

My great-grandfather is buried on Lookout Mountain, his grave overlooking the Great Plains and the Rockies, far from the Cedar Mountain, Wyoming, resting place that he had requested before he died. This grave, chosen for him by family when he no longer had a say in it, is near Denver, Colorado, where I lived for a year, where I worked, where my son was born and where my wife was murdered.

Standing there, with the white-topped peaks in the distance forming part of the great spinal column that connects the forests of western Canada to the dry-aired flatlands of New Mexico, the senses are struck by the spicy scent of pine needles in the air while the quick breeze encourages brisk movement. The wildlife – the bison, the elk, the great bears – drift from hilltop to plateau, glancing warily at visitors. There is no restlessness here, just slow movement and ongoing life. This is a separate place and although it was not my great-grandfather’s desired grave, I feel sure that he would have been able to approve of it.

My father, Isaac – who, like me, was named for his great-grandfather – never visited Lookout Mountain, never in fact set foot outside England during his lifetime, but he always spoke of it with authority, the same authority which he lent to his study of the life of the grave’s occupant, who died in 1917, the year before Isaac’s birth. My most recent visit to the grave was my third. My first came a few weeks after arriving in Denver in 1998 and then again about a year later. Isaac assumed that I would be here more often – he refused to believe that my wife and I would come to Denver for any other reason than to be closer to Lookout Mountain and it remains much more his place than mine. I could never equal his passion for our family history, his need to have an illustrious past, a celebrated ancestor. He was a storyteller with just one story to tell, but that story was the story of a lifetime. I was interested, I was certainly intrigued, but Lookout Mountain has never been my haven. In fact, it’s represented something which has caused me only pain. My most recent visit came about because Isaac had died and there was something that I needed to do there.

I’m a child of the 1970s, born on the first day of the decade, when Isaac was fifty-two and a first-time father. He met and married my mother when he was fifty. From time to time he would tell me stories about his childhood, his youth, but he gave very little away, his own life and history being of little interest to him. In fact, I never really got to know where he had come from or what his own childhood was like. Instead, the stories he told were about his grandfather and he gave me his name, William, which I kept in its full form, unlike my ancestor who opted for the diminutive Bill. I was probably six or seven before I realised that my father was the same age as most of my schoolfriends’ grandparents. It confused me a little, and scared them, but I didn’t ask many questions. I barely knew my mother. She left home when I was four years old, divorcing my father and marrying a doctor before emigrating to Canada, where she still lives. We rarely speak.

It’s hard to know whose story this is. It’s partly mine and it’s partly Bill’s, but in the centre comes Isaac, telling me all he knew about his grandfather and making me who I am at the same time. Three generations of men, separated by long periods of time and place, in some ways none of us really related to the others at all. I spent my life running away from Isaac but now that he’s dead, I find myself keeping his memory alive more and more through the stories.

Isaac’s prized possession was mounted on the wall of our living room and I knew better than to take it down without permission. It was a Smith & Wesson handgun, manufactured in Kansas in 1842 and given to Bill by his own father as a reward for saving his life when he was a child of nine. An American, Bill’s father had been taken as an Abolitionist by some Pro-Slavery men after he gave a speech near the Salt Creek trading post in Missouri where he refused to endorse the admittance of slavery into the new state of Kansas. Having been part of the original settlement of Iowa when it was brought into the union, Bill’s father had been entrusted with leading the settlement of the region. As such, his was a voice which was given credence by the local population. When he spoke, his words carried almost the weight of government, a future government, and his policies and ideals could settle plans for the manner in which the new state would be run. He was invited to speak on that day by the men of Missouri who believed, wrongly, that he would endorse their plans for the ratification of slavery. When he did not, and when he spoke vehemently against such a policy, he was stabbed by a local man and although the wound was not fatal, from that moment on his life was under threat.

‘Is it loaded?’ I asked Isaac, time and time again throughout my childhood, staring at the carved wooden handle and rust-tinged metal. ‘Could it kill someone?’

‘It might be,’ he replied, always refusing to let me know one way or the other. ‘The thing about that gun is that it’s so old and it’s seen so much gunpowder run through its chamber over the course of its life that it’s likely to explode in the hands of anyone who takes it down and tries to mess with it without permission. Be warned now.’ This was his way of ensuring that I did not touch the gun. ‘I’m trusting you now, William,’ he said, pointing towards it but staring at me fiercely, fierce enough to make me know that there would be few things he would ever say to me in his lifetime that would carry such a weight of responsibility. ‘You’re never to take that gun down, do you hear me? Never without asking me first.’

I nodded. I heard him all right. But I was a child at the time and I didn’t necessarily listen.

Bill’s story, as Isaac tells it, began in an Iowa log cabin in 1846. He was probably one of the first children to be born in the newly settled state but his childhood on those flat plains ended after only five years when the barren land was swapped for the Mississippi River as the growing family moved to LeClair. When I think of his days growing up along those banks – a Mark Twain childhood – it fills me with envy, so far removed is it from my own London upbringing. Only two generations separate us, but Bill’s and my life are so different and I can no more understand his life in the nineteenth-century American mid-west then than he could have predicted mine now. And yet I do, I think of it often, I write of it now, for as separated as we are, he is part of my chain and my ancestry, p

art of my links to a time and place which no longer exist. The west. The settling of the Americas. The basics of Isaac’s stories are all my father and I had to connect us and that’s where they were set, almost every one.

Although he had enjoyed little formal schooling himself, Isaac was a keen educator when it came to his only child and tolerated no truancy on my part. Playing the role of both father and mother he got me ready for school in the mornings, prepared my lunch and dinners, and sat with me in the evenings to help me with my homework. To be allowed a sick day from school I practically had to be admitted to hospital. I was a solid student and did well; there was no alternative offered to me. When I went to bed at night, Isaac’s day also ended for his life was empty without me and so, to fill those hours before sleep, he drank whisky.

It’s easy to see why he wanted me to make something of my life and to excel at everything to which I put my mind. For he had led a carefree existence as a child, unmonitored by his father Sam, and left school when he was only fourteen, a reasonable age to begin the career at which he was to prove quite successful for a time. That of petty criminal.

Isaac was a small man, in stature if not in personality, and even in his late twenties he could have easily passed for a teenager. He used his lack of size to assist himself in his career as a burglar and a thief. He was good at it too, it has to be said, managing to make quite a living at his chosen profession until, inevitably, a series of misdemeanours saw him jailed for four years, a period which counted for almost half his thirties, after which he never again laid hands on anything which did not belong to him. Whatever took place when he was inside, he turned his back on his past when he was released and worked in a variety of jobs – labourer, taxi driver, builder – until he met my mother and settled down with a small painting and decorating business which paid little but sufficient to support comfortably enough the three of us, soon to be the two of us.

I think my father wanted a son who would do the things that he had never done. He gave me opportunities but watched over me at the same time and never allowed me to squander the chances which came my way. He felt he had done nothing of substance with his life, unlike his idolised grandfather, and wanted me to be more like the older man than like him.

Bill, on the other hand, received scant education and expected less. His brief studies were prematurely ended when he was nine years old after an incident which led to his sudden exile from Mississippi and near imprisonment. He was bullied at school by an older boy, Stephen Gobel, who was his rival for the affections of one Miss Mary Hyatt. A long-simmering feud erupted into a fight, during which Bill drew a small dagger from his pocket and stabbed Master Gobel in the thigh. The sudden appearance of so much blood, not to mention the squealing of the injured boy like a stuck pig, led Bill to flee the school and join a freight train headed for Fort Kearney, where he spent the summer herding cattle, a far cry from the regular summer activities of the nine-year-olds of my generation.

Like Bill, I too became a steady brawler during my early years in school. Streamlined and cosseted at home, I sought my opportunities at school to prove myself and to assert my individuality. I made the early mistake of talking about Bill’s life and adventures before realising how disbelieving my peers would be and paid for it for some time before I decided that the slightest slur against my alleged ancestry would call for severe action on my part. Unlike Isaac, I was not a small child and was capable of sizing up to anyone in the schoolyard with only a modicum of fear. I never betrayed it though and made sure to get my blows in first, proving my seriousness in a fight almost before it had even begun. Often my adversaries would be surprised by my attitude and back off; at other times they would prove equal to the challenge and beat me senseless. Either way, it infuriated Isaac.

‘It doesn’t matter who wins or loses,’ he said when I came home one afternoon, a little bruised perhaps, a streak of dried blood slashed roughly across my cheek, but nonetheless the victor in my latest playground clash. ‘You don’t go to school to treat the place like a boxing ring.’

‘But they were making fun of—’

‘It doesn’t matter what they were doing, William, that’s not why I send you there,’ he shouted. ‘Look at you. Look at that cut over your eye.’

‘But I won,’ I protested, expecting him at least to be impressed by the fact that if I was going to involve myself in fighting then I could come out on top.

‘Worse still,’ he said however, causing me no end of confusion and self-pity. ‘I’d rather see you lose. At least then I’d know how badly the fight ended and feel that you might have learned some lessons from it. What does the other boy look like anyway?’

I shrugged. I wasn’t sure how to phrase it. ‘He’ll be all right,’ I muttered, shuffling my feet on the ground and refusing to return his gaze as I recalled the sight of a split-lipped boy sniffling and limping his way back home, one eye beginning to seal in upon itself, throwing curses at me in defeat, threatening what he would do to me the next time that he caught up with me. ‘He’ll live.’

‘You’re a disgrace to yourself,’ he told me. ‘Picking on a bunch of kids.’

‘But I’m a kid!’

‘That’s no excuse. When your great-grandfather was a boy, do you think he went around causing fights for no reason? Do you think that’s how he went on to achieve so much?’

‘Probably,’ I said, refusing to be beaten in any argument, physical or verbal. ‘He wasn’t exactly famed for his pacifism, was he?’

Isaac squinted at me and held back. I could see him working this through in his mind, wondering where I had learned words like pacifism and attitudes like sarcasm at the same time. That was the start of it, he must have realised. The point where I was growing up and could slip away from him if he was not careful.

‘Don’t let me down now, William,’ he said eventually in a quiet voice. ‘There’s a lot expected of you. A lot to live up to. I gave you your name for a reason.’

Sometimes, for no reason other than the fact that I could, I hated and resented my great-grandfather in equal parts.

The first winter that Bill spent in Kansas was a preparatory one. The Enabling Act was before Congress, awaiting ratification, and when it was finally passed it allowed settlers to stake claims on the land, to settle down and earn a living through the farms. The family had moved there some time in advance of the decision, anticipating the bill’s approval, and were able to claim a portion of the land, where they built their home and started their working of the soil. They planted crops and reared livestock. Another child was born. Bill became familiar at an early age with the tribes who had lived there before the settlers arrived and learned to speak some of the Kickapoo language which dominated the area. He became fluent quite easily and this helped him become friends with the Indian children who lived nearby.

His friendship with the tribes who would ultimately be driven off their land by the American settlers led to his early initiation into the Mide religion, with which he was enamoured for a brief time during childhood. Traditionally, belonging to the Mide involved initiation through the learning of stories about the Kickapoo past, their slow drift westwards across the continent, and their belief in the value of herbal medicines to counter any illness and mark any significant event in a man’s life. They were a peaceful people, given to ritual and tradition, and although they must have been wary of the arrival of the white men, they were at first treated well, and as neighbours, unlike many of the other tribes of the Northern American continent at that time, and the two cultures settled into a peaceful cohabitation.

Famously, the family arranged an enormous barbecue on their new land to cement a friendship with the Kickapoo people. The barbecue lasted for two days and several hundred Indians were fed the slaughtered animals which formed part of their farm. Bill’s mother introduced them to coffee, which they had never tasted before; the gradual replacement of one culture with another had begun, masked as kindness, and was being replicated across the new U

nited States.

For the first time Bill had begun a friendship with an Indian boy, whose name was not passed down to us, and some of the skills of the native culture were shared. They spent long afternoons shooting birds from the sky with bows and arrows, no doubt missing more than they ever managed to kill, but it was an education and a beginning into learning the ways of the Indian which would benefit Bill as his career developed.

My knowledge of other cultures, in comparison, was limited to those few students in my class who were black, or Pakistani, perhaps the odd European exchange student. Each was treated with varying degrees of suspicion and each, in general, kept with those who they knew best. Unlike my great-grandfather’s early days in Kansas there were not many attempts made in my south London comprehensive to integrate our English culture with that of the immigrant or the foreigner. Fights would break out in the schoolyard based on the simple existence of difference between us, a difference we could not define but which in some strange way threatened us. As a boy, I tried not to involve myself in these confrontations, confused as I was by the differences between right and wrong. Isaac’s ongoing stories of my great-grandfather’s life and times, both within and without the native people of the west, had created a feeling of ambivalence within me towards other cultures. I knew that Bill had begun his life as a friend of the Indian, but I also knew that he had eventually taken up arms against them in order to fulfil the role which he had created for himself as an archetypal hero, and then he had finally exploited them in his later life by helping to create the kinds of myths which, when properly continued, transpose themselves into history and become the very things which are ultimately taught as fact.

Isaac, on the other hand, would never question either Bill’s motives or his integrity, believing that his grandfather’s subtly changing attitudes over the course of his seventy years reflected not an alteration in his own point of view for mercenary or personal reasons, but rather a change in the behaviour and attitudes of the Indian tribes themselves. Of course, this was based entirely on his belief in his grandfather, his utter and unswerving pride in that man’s achievements and life, and the vicarious manner by which he sought to add splendour and mystique to his own at times unfulfilling existence. Having said that, the integrity of which I speak is one which was matched by my father’s own life and value system. He may have tried to dominate both our lives with his overpowering sense of personal history and he may have ultimately paid a high personal price for that perseverance, but by God he believed in it and I’m not sure I’ve ever found anything to place my faith in quite so strongly as Isaac placed his faith in the continuing momentum of his ancestry.