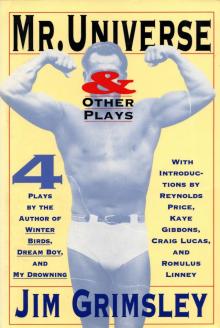

MR. UNIVERSE

Jim Grimsley

MR. UNIVERSE

AND OTHER PLAYS

BY JIM GRIMSLEY

Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill

For Faye Allen and Del Hamilton

Contents

Introduction

Romulus Linney, on Mr. Universe

Mr. Universe

Reynolds Price, on The Lizard of Tarsus

The Lizard of Tarsus

Kaye Gibbons, on The Borderland

The Borderland

Craig Lucas, on Math and Aftermath

Math and Aftermath

I would like to acknowledge support from the Fulton County Arts Council, the City of Atlanta Bureau of Cultural Affairs, the Georgia Council for the Arts, the Rockefeller Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Mary Ellenberger Camp Foundation, at various times during the writing, development, and production of these plays. I have no way to express fully my deep indebtedness to Seven Stages, and to all the people who have worked there, for more than a decade of support for my work.

Introduction

The world, and in particular the world of writing, offers few torments as exquisite or pleasures as sweet as the opening night of a play. Here I have written all these words for people to say to one another, described all these pictures, sat through rehearsals, and suddenly here it is in front of me on a stage, all cleaned up, about to announce itself. A play that I have written is to be spoken and walked through, night after night, and tonight is the very first time.

Each play has its own terrors, and the creation and production of a script is an act unlike any other, borrowing from novel-writing, literature classes, the psychologist’s couch, and the motivational seminar. A novelist can afford to be private and reclusive; a playwright may have tendencies in that direction, but sooner or later there will be a rehearsal or a party after a rehearsal or a performance or a question-and-answer session: sooner or later the nature of theater will drive the playwright public, at least for a while.

The publication of this book, collecting some of the plays I have written over the last decade and a half, is an opening of a different kind. I have been looking over the pages of these plays again, visiting them as if they were relatives I hadn’t seen in a while, remembering the first time I saw the Muscle Man pull off his clothes in Mr. Universe, the first night I watched Pug Montreat shoot himself in the mouth in Math and Aftermath, the first time Eleanor stood in the window looking across the fields in The Borderland, and Sol Heiffer’s first walk across stage with the crucified lizard on her back in The Lizard of Tarsus.

To write a novel is a delicious siege; one camps in front of a story as though it were a city and waits. To write a play is like crossing a river by leaping from rock to rock; there are always those pauses, those moments of empty space, between the rocks. To publish a novel is a quiet process, at least as far as I have known it, with faxes and phone calls and thoughtful conversations, and parcels traded back and forth via overnight express. To produce a play is rarely a quiet business, with the fuss of meetings, the egos of artists and designers, the forced pressure of the short rehearsal. The two ways of writing provide a good tension, and each changes the other and makes it better.

But there is nothing I have known in fiction that can compare with sitting in a theater on the first night a play is performed, hearing spoken aloud the words that were delivered to the writer in silence. There is nothing like going back again and again and hearing how the language can change even when the words do not, how meaning can ripple across the space of the theater like something visible. A novelist cannot sit inside the reader’s mind and feel the response the novel creates, but a playwright can sit with the audience and feel how they respond to the play.

The writing of a play or a book is a whole, and taking the process apart to examine it serves no purpose for the person who is doing the work. It is possible to make up a reason for writing or a theory of what makes a play, but in the end what matters is the play that gets made. The reason I make a play is so that I can sit there night after night and have the feeling of the words washing over me, of the scenes and voices out of my mind moving on the stage.

These plays share that need—to transform words into motion in order to come to some moment of contemplation, in the midst of all that motion, that cannot itself be put into words or experienced in anything but silence. Here are four plays with puzzles inside them, with nothing neatly resolved or explained, which have already made the long journey to one stage or another. They are my attempt to draw some outline around the territory of mystery so that I myself might enter and others might follow if they so choose.

Jim Grimsley

Romulus Linney, on Mr. Universe

The discovery of our common humanity in unlikely places makes for lively theater, but only as long as the humanity is as real as it is lively. False notes here quickly betray opportunistic sewer shock, not a procedure that holds up on a stage, where flesh and blood face flesh and blood, where honesty and truth as well as shock are mandatory. Otherwise, how do very strange beings placed before us have anything to do with our “normality”? We go to the theater to find ourselves in Shakespeare’s universal mirror held up to nature, and find ourselves we must, no matter in what place or in what action or in what characters.

At the center of Jim Grimsley’s Mr. Universe is a mute young bodybuilder covered with blood. Around him and his never-explained mystery circle, in various stages of emotional and sexual excitement, a decent drag queen, a vicious one, and a prostitute from whom God save old men. This takes place in New Orleans, which can often seem unreal, a Disneyland of Vice. Here is the real thing, populated by truthful citizens of its lower depths, those who hustle its streets after hours when tourists are safe in their hotels. That these vivid wrecks can be delightful as well as appalling, touching as well as murderous, that their concerns awake our own, about children, self-preservation, and love itself, is a testament to Jim Grimsley’s refusal to judge them, to condescend to them, or finally, to exploit them.

The action of Mr. Universe is admirably clean and simple. Its world is simply as is. But the dialogue of the play is something else. Here, in what may seem by now the ordinary back-and-forth of gay chatter, lies the jewelry of the play. For what these people say to each other hits home. There is here a world of conflicting values, centering around such permanent matters as honor and betrayal, dignity and abasement, compassion and hatred, and the eternal essentials of drama, love and death. Loving and dying and speaking. You experience this in the exact and particular way these outlandish characters talk to each other, as much as in what they say. Line after line seems struck off from a living being, not a character in a play who must advance its action. Free from the fatal flaws of self-descriptive speeches, returning subjects, or long tales of the past, the people of Mr. Universe speak as we spoke to each other in our own past. As far as we may individually be from camp or bitchery, we hear them, and we understand their fear and rage and love, the basic emotions of life that drive them, and us. The unsolved mystery of the bloody bodybuilder becomes a sort of place, a safe thicket from which we can see amazing animals as they pass by. We have never met anything like them, not because they are so strange, but because they are so much like those elements of our own makeup we never acknowledge. The mirror is held up to nature, very peculiar but very truthful nature, and we see ourselves whether we like it or not. At the beginning of the play, we don’t. At the end, we do. In between, a work of stage magic has shown us what we did not know we knew, never felt what was there to feel.

And we sense, in the anonymous author all playwrights must remain, lurking behind the different characters, a superior and unique artistic sensibility. Mr. Grimsley is a writer for many seasons. The poetic diction of his devastatingly bruta

l novel Winter Birds is an example of how much this writer can do, if we let him do it. His novels are now receiving the attention they deserve. Let us hope his plays will do the same. But here there is a problem.

Mr. Universe is challenging theater, especially for producers. It must be not just well acted, but brilliantly acted, or the underlying humanity will not emerge. This intense creation can easily play as nothing more than a sketch of violent sex life in New Orleans. Its stern delicacy and underlying fidelity to its world would be trivialized only too easily by a theater interested in immediate and obvious effect, which in this case would be camp. Think of the very best realistic actors you know, from both stage and screen, when you read this play—Al Pacino, for instance, or the young James Dean—and you can imagine something that would in my opinion, jump to a much different life on the stage than satire or lower depths despair. It would be life as it is, and it would be wonderful.

Jim Grimsley’s characters are what let us hope God preserves us from, but we laugh and nod while we shudder. Keats was right. Beauty is truth, truth beauty, and Jim Grimsley got it right in Mr. Universe.

MR. UNIVERSE

Mr. Universe premiered at Seven Stages Theatre in Atlanta in August 1987, in a production directed by Steven Kent, featuring Mike Jones as the Saxophone Player, Rebecca Ranson as Juel Laurie, Faye Allen as the Police Woman, Del Hamilton as Vick, Tim Martin as Judy, Jeff Lewis as the Muscle Man, and Donna Biscoe as Katy Jume. Costumes were designed by Stephanie Kaskel, and composition and sound design were by Michael Keck.

The play was subsequently produced by Woodie King Jr. at New York’s New Federal Theatre in March 1988, again directed by Steven Kent, with Nao Takeuchi as the Saxophone Player, Shami Chaikin as Juel Laurie, Vicki Hirsch as the Police Woman, Del Hamilton as Vick, Peter Toran as Judy, Charles Mandracchia as the Muscle Man, and Donna Biscoe as Katy Jume. Costumes were designed by Stephanie Kaskel; lighting, by Linda Essig; and set, by Steven Perry.

The song “Your Daddy” is an original composition by Jim Grimsley for Mr. Universe.

PLAYERS

The SAXOPHONE PLAYER

JUEL LAURIE, a woman in her late forties or early fifties, widow of Vanice

A POLICE WOMAN

VICK, a man in his early forties

JUDY, a man in his early twenties

The MUSCLE MAN, a bodybuilder

KATY JUME, a woman in her late twenties or early thirties

SETTING

The play is set in 1979 in New Orleans.

ACT 1

SCENE 1:

Esplanade Avenue, a night in late spring.

Lights rise on the SAXOPHONE PLAYER, who is rehearsing in the cool night, playing traditional New Orleans jazz.

Enter JUEL LAURIE, dragging a bag of garbage.

The bag has a hole in it, and she trails garbage behind her.

She stops once or twice to pick up the garbage she has dropped, returning it to the bag but never quite comprehending that the bag has a hole in it.

Finally she reaches the garbage can and puts the bag in it.

She walks away from it a few steps, then stands still, thinking.

Enter POLICE WOMAN, who watches the SAXOPHONE PLAYER and JUEL LAURIE.

JUEL LAURIE returns to the garbage can, takes out the bag, opens it.

She begins to lay out the garbage neatly around her.

The SAXOPHONE PLAYER lets the music soften and die away.

Sits and begins to polish his horn, clean the mouthpiece.

Lights fade on him.

JUEL LAURIE finishes arranging the garbage and speaks.

JUEL LAURIE. I should’ve brought me some paper so I could do a list. I hate to throw this stuff away and tomorrow I won’t even remember what it is. Looka this. (Holds up an old shoe.) I knew it. I knew. I never meant to throw this out. It ain’t but one shoe but it’s a good one. (Smells it.) Smells just like Vanice, Lord help me. Vanice, I says, your feet stink because you never wash from between your toes. I told him.

(The POLICE WOMAN approaches.)

POLICE WOMAN. Excuse me ma’am, what are you doing?

JUEL LAURIE. Oh God, did I do a crime?

POLICE WOMAN. You can’t leave all this stuff laying around.

JUEL LAURIE. I was making a list. Are you going to put me under suspicion?

POLICE WOMAN. I just want you to clear up this mess, ma’am.

JUEL LAURIE. This is a good shoe.

POLICE WOMAN. Yes ma’am, you can keep the shoe.

JUEL LAURIE (bagging up the garbage). You ain’t seen Vanice running around here have you? He left the house this morning without no belt on, and his pants so baggy they be all down his legs.

POLICE WOMAN. Is Vanice your husband?

JUEL LAURIE. Lord yes, everybody knows that. Everybody knows Vanice, he’s got big feet. Why do you work for the police? Do you like crime?

POLICE WOMAN. No ma’am.

JUEL LAURIE. Has they been any good crime around here today?

POLICE WOMAN. Found a dead man in a motel over to the Faubourg. Don’t know who he is.

JUEL LAURIE. Did he have a belt on?

POLICE WOMAN. Didn’t have much of nothing on from what I hear.

JUEL LAURIE. Can’t be Vanice then, he ain’t never naked. (Ties the bag closed and puts it in the garbage.) I got to go fry some boloney. You want a piece?

POLICE WOMAN. No ma’am. You don’t let no strangers in the house now.

(Exit POLICE WOMAN.

Enter VICK, in high drag.

He stays out of sight until the POLICE WOMAN is gone.)

VICK (to JUEL LAURIE). What did she want with you, Mistress Laurie?

JUEL LAURIE. Hey Vick. That’s a mighty nice dress you got on, did you go back to work at JuJu’s?

VICK. No ma’am, I’m just going out. What did that policewoman want?

JUEL LAURIE. She got me under suspicion. She found a dead man in a motel, naked as God, over to the Faubourg.

VICK (laughing). She don’t think you killed him, honey.

JUEL LAURIE. She might think I did, and Vanice ain’t here to testify. Lord I need him so bad.

VICK. Mistress Laurie, now I’ve told you, you got to put him out of your mind, you can’t bring him back.

JUEL LAURIE. The pohlice are coming back, you know that, they don’t never come just once. She let me have my shoe but she’s coming back for me.

VICK. Sweetheart come with me, come on. That’s right. We got to get you back in your apartment right now.

JUEL LAURIE. I got to cook my supper. Fry some boloney.

VICK. Yes ma’am, you do.

JUEL LAURIE. Will you be home?

VICK. Judy and me are going out for a little while but we’ll be back later, you can knock on the door when the light’s on.

JUEL LAURIE. Katy ain’t home. I know that. She out walking in a cheap dress, left her kitchen window wide open.

VICK. I know honey, I ain’t seen Katy in a few days. But you’ll be all right. Just keep the front door closed and come see me and Judy later when we get back.

(Enter JUDY, also in drag.)

JUDY. What’s wrong with her?

VICK. She came out on the street and got a little confused.

JUDY. I would not call that a little confused.

JUEL LAURIE (to VICK). Are you still taking up with him? (Indicates JUDY.)

VICK. Yes ma’am, Mistress Laurie, and Lord knows I don’t know why. (To JUDY.) I’m just walking her back to her apartment, I’ll be right back.

JUDY. You better be because I’m not waiting around, not long as it took me to get this garter belt right.

VICK. Oh hush, it won’t hurt you to wait two minutes.

JUDY. I know it won’t hurt me dear, but what about you, you’re aging every second.

VICK. Kiss my ass.

(Exit VICK and JUEL LAURIE.

The SAXOPHONE PLAYER has finished his instrument cleaning and stands, begins to play a slow, mournful blues—Judy’s t

heme, “Your Daddy.”

JUDY struts up and down the stage, timing her sashay to the music.

Enter VICK, putting on lipstick.

Music dies away.

The SAXOPHONE PLAYER withdraws to his playing area; lights down on the SAXOPHONE PLAYER.)

VICK. Sweetheart what are you trying to do, make this month’s rent?

JUDY. You always get jealous because I have better legs than you do. Don’t you think you’ve put on enough lipstick by now?

VICK. Please don’t flap your hand in my face. And who do you think you are teaching me about makeup when I have worked on the professional stage. You can’t teach me anything about being a woman, I have done it all.

JUDY. I bet you have. All at JuJu’s Hideaway.

VICK. Your mama never worked any better place honey, not even with real tits.

JUDY (haughtily). I do not want to talk about my mama if you don’t mind.

VICK. Are you ready to go? (Takes a few steps.)

JUDY. I am not interested in one bar up that street, I am tired of old men and chicken.

VICK. Well I am not going to ruin my good gown walking up and down the waterfront to find you a sailor.

JUDY. Why not?

VICK. You are completely out of your mind; the sailor never sailed who would give you the time of day.

JUDY. But you promised.

VICK. Just exactly when did I promise to walk down to the waterfront and get myself killed?

JUDY. You said you thought it would be fun.

VICK. I said I thought it would be fun if we could fool them boys, but we can’t.

JUDY. All we ever do is go to the same old bar and drink the same old drink and talk to the same old men.

VICK. I am not having this discussion with you again.

JUDY. I want to have some fun Vick, please take me down to the river, please please. I’ll be such a good girl you won’t even know me. We’ll just walk down there and walk back, we don’t have to stay.