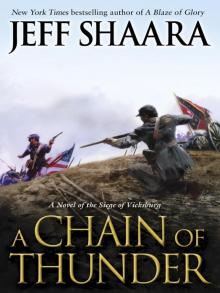

A Chain of Thunder

Jeff Shaara

A Chain of Thunder is a work of historical fiction. Apart from the well-known actual people, events, and locales that figure in the narrative, all names, characters, places, and incidents are the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to current events or locales, or to living persons, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2013 by Jeffrey M. Shaara

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Ballantine Books, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

BALLANTINE and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Shaara, Jeff.

A chain of thunder: a novel of the Siege of Vicksburg / Jeff Shaara.

eISBN: 978-0-345-52740-0

1. Vicksburg (Miss.)—History—Siege, 1863. 2. United States—History—Civil War, 1861–1865—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3569.H18C54 2013

813′.54—dc23 2013009360

www.ballantinebooks.com

Jacket design: Dreu Pennington-McNeil

Jacket illustration: © Robert Hunt

Web asset credit: Excerpted from A Chain of Thunder by Jeff Shaara copyright © 2013 by Jeffrey M. Shaara. Published by Ballantine Books, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

v3.1

Verily, war is a species of passionate insanity.

—MARY ANN LOUGHBOROUGH,

CIVILIAN, VICKSBURG, MISSISSIPPI

TO THE READER

This story focuses on the campaign that results in the siege and conquest of the crucial Mississippi River city of Vicksburg. It is the second volume of a series that explores the often-overlooked story of the Civil War in the “west.” Quotation marks are necessary because to our eye today, “west” would certainly take us far beyond the shores of the Mississippi River. Yet, throughout much of the Civil War, events that occurred just west of the Appalachian Mountains were often overshadowed by the great battles to the east, which took place close to what we would refer to now as the great “media centers” of their day. Those events, from Kentucky to the Gulf Coast, from Texas and Arkansas, to Missouri and even New Mexico, were as bloody and as significant to our history as what took place in and around Virginia.

Throughout the war, both sides understand the critical importance of railroads and rivers, the two primary means of moving goods (and people) across vast distances. In the first volume of this series, A Blaze of Glory, the issue, primarily, is railroads, specifically the Union’s effort to capture a critical rail junction at Corinth, Mississippi, which results in the Battle of Shiloh. Now, roughly one year later, the Federal armies, under the command of Ulysses S. Grant, seek to further divide and thus weaken the Confederacy by seizing the last major Southern obstacle to Northern control of the Mississippi River, the city of Vicksburg.

This story follows several pivotal characters through the spring and summer of 1863, as Grant and his generals push through the state of Mississippi, facing off against Confederate forces under the command of General John Pemberton. Some of the voices in this story will be familiar to any student of the war: Generals William T. Sherman and Joseph Johnston, as well as Grant and Pemberton. Brought forward from the first volume is Private Fritz “Dutchie” Bauer of Wisconsin, whose baptism of fire at Shiloh shapes the kind of soldier he will become. The fourth primary voice is something of a departure for me. The story of Vicksburg is not just a story of battles and generals, and so my research sought out the voices of the civilians, the citizens of Vicksburg, who suffer mightily and whose tenacity is a part of this story that cannot be overlooked. So often in war, civilians are tragically involved simply by being in the way. In Vicksburg, their ordeal affects the way many civilians throughout the divided country will come to view the horrors of this war. They come to represent what the conflict has become, evolving from what some saw as a gentlemen’s spat between men of honor, into a brutal war that will deeply impact towns and cities, and their inhabitants. There is a poignant comparison to be made between Vicksburg and what has taken place a few months earlier at Fredericksburg, Virginia. In December 1862, the citizens of Fredericksburg embark on a mass exodus away from their town, fearing the horrific battle that does indeed occur. In the spring of 1863, the residents of Vicksburg are offered the same opportunity for escape, and yet an overwhelming percentage of them decide to remain in their homes. And thus, one of those voices is essential to telling this story, nineteen-year-old Lucy Spence.

I am not an academic historian. If you know of my work, you know that, from the Revolutionary War through World War II, my focus has been on the people, whose accomplishments and failures have become a visceral part of our history. This is a novel by definition because there is dialogue, and even if a character is well known historically, the point of view has to be described as fictitious. My research has always focused on a study of the original source materials: diaries, memoirs, collections of letters, the accounts of the people who were there. Often, when it fits the flow of the story, I quote their words verbatim. But in every case, their experiences and the events from the historical record are as accurate as I can portray them. If I don’t believe in the authenticity of the voices here, neither will you.

I am frequently asked if there are veiled references in any of my stories to more modern events, a nudge-nudge wink-wink that what I’m really offering is a parable to more modern times. Absolutely not. There is no judgment here, no history-in-hindsight, no veiled references to any more recent event or person.

One enormous irony of the campaign for Vicksburg is that it ends exactly one day after the conclusion of the Battle of Gettysburg. Obviously, since Gettysburg is much closer to both Washington and Richmond, that battle has always received enormous attention. But it is a point of debate even today whether Vicksburg or Gettysburg had the greater impact on the outcome of the war. That debate I leave to others. This is a story told through the eyes of the characters, and to most of them, the events they experienced were the most important of their lives. To me, that’s what makes a good story. I hope you agree.

JEFF SHAARA

APRIL 2013

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Epigraph

TO THE READER

LIST OF MAPS

SOURCES AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

INTRODUCTION

PART ONE Chapter One: Spence

Chapter Two: Sherman

Chapter Three: Bauer

Chapter Four: Sherman

Chapter Five: Pemberton

Chapter Six: Bauer

Chapter Seven: Sherman

Chapter Eight: Bauer

Chapter Nine: Pemberton

Chapter Ten: Sherman

Chapter Eleven: Johnston

Chapter Twelve: Sherman

Chapter Thirteen: Pemberton

Chapter Fourteen: Pemberton

Chapter Fifteen: Grant

Chapter Sixteen: Pemberton

Chapter Seventeen: Pemberton

PART TWO Chapter Eighteen: Spence

Chapter Nineteen: Bauer

Chapter Twenty: Sherman

Chapter Twenty-One: Pemberton

Chapter Twenty-Two: Bauer

Chapter Twenty-Three: Sherman

Chapter Twenty-Four: Spence

Chapter Twenty-Five: Bauer

Chapter Twenty-Six: Sherman

Chapter Twenty-Seven: Spence

Chapter Twenty-Eight: Pemberton

Chapter Twenty-Nine: Bauer

Chapter Thirty: Sherman

Chapter Thirty-One: Spence

Chapter Thirty-Two: Pemberton

Chapter Thirty-Three: Bauer

Chapter Thirty-Four: Spence

Chapter Thirty-Five: Sherman

Chapter Thirty-Six: Sherman

Chapter Thirty-Seven: Pemberton

Chapter Thirty-Eight: Spence

Chapter Thirty-Nine: Bauer

Chapter Forty: Bauer

Chapter Forty-One: Sherman

Chapter Forty-Two: Spence

Chapter Forty-Three: Pemberton

Chapter Forty-Four: Grant

Chapter Forty-Five: Spence

Chapter Forty-Six: Bauer

AFTERWORD

Other Books by This Author

About the Author

LIST OF MAPS

OVERVIEW OF MISSISSIPPI THEATER OF WAR

GRIERSON’S CAVALRY RAID

GRANT MOVES DOWNRIVER

GRANT INVADES MISSISSIPPI

POSITIONS ON MAY 13

SHERMAN AND MCPHERSON AT JACKSON

POSITIONS ON MAY 15

THE BATTLE OF CHAMPION HILL—FIRST CONTACT

THE BATTLE OF CHAMPION HILL

S. D. LEE RETREATS—CUMMING BREAKS

BOWEN’S COUNTERATTACK

BATTLE OF BIG BLACK RIVER BRIDGE

SIEGE LINES ON MAY 18

SIEGE LINES MID-JUNE

SOURCES AND

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

In response to numerous questions from readers, asking for some specifics on the original sources I draw upon, the following is a partial list of those figures contemporary to the events in this book whose accounts were particularly useful:

FROM THE NORTH

Lucius W. Barber, 15th Illinois

Cyrus F. Boyd, 15th Iowa

Sylvanus Cadwallader

Ransom J. Chase, 18th Wisconsin

Wilbur F. Crummer, 45th Illinois

Charles Dana

Thomas J. Davis, 18th Wisconsin

John J. Geer, USA

Philip H. Goode, 15th Iowa

Ulysses S. Grant, USA

Orville Herrick, 16th Wisconsin

Virgil H. Moats, 48th Ohio

Osborn Oldroyd, 20th Ohio

Hosea Rood, 12th Wisconsin

William T. Sherman, USA

Leander Stillwell, 61st Illinois

The Men of the 55th Illinois

FROM THE SOUTH

Emma Balfour (Vicksburg)

Sid Champion, 28th Mississippi Cavalry

William Cliburn, 6th Mississippi

Thomas Dobyns, 1st Missouri

Rev. William Lovelace Foster (Vicksburg)

Joseph E. Johnston, CSA

Rev. W. W. Lord (Vicksburg)

Mary Ann Loughborough (Vicksburg)

Lucy McRae (Vicksburg)

Dora Miller (Vicksburg)

John C. Pemberton, CSA

Samuel J. Ridley, 1st Mississippi

Charles Swett, Warren (Mississippi) Light Artillery

James M. Swords (Vicksburg)

Mollie Tompkins (Vicksburg)

William H. Tunnard, 3rd Louisiana

With every book I’ve done, I must rely on a variety of research sources, including the generous contributions of material from historians and readers. The following is a partial list of those to whom I offer my sincere thanks.

Tim Cavanaugh, Chief Historian, Vicksburg National Military Park

Dr. J. William Cliburn, Hattiesburg, MS

John H. Ellis, Matthews, NC

Patrick Falci, Rosedale, NY

Christopher Gooch, Cane Ridge, TN

Colonel Curtis J. Herrick, Jr., USA (Ret.), Annandale, VA

Evalyn E. Kearns, Atlanta, GA

Bruce Ladd, Chapel Hill, NC

Stephanie Lower, Gettysburg, PA

Keith Shaver, Murfreesboro, TN

Bob Springer, Jacksonville, FL

Paul Thevenet, Nazareth, PA

Edward Vollertsen, Monticello, FL

Nancy Warfle, Warren Centre, PA

Terrence Winschel, Chief Historian (ret.), Vicksburg National Military Park

For a larger version of this map, click here.

INTRODUCTION

From the earliest months of the Civil War, many of the strategists and political leaders of both sides consider control of the Mississippi River the key to victory. The original “Anaconda Plan,” as designed by Union general in chief Winfield Scott, includes control of that river as an essential part of any strategy that will ensure victory (along with a total blockade of Southern seaports). In the South, Jefferson Davis is equally determined to maintain control of the river, understanding that free access for Federal troops and supplies along the waterway will split the Confederacy in two and eliminate the valuable trans-Mississippi states of Texas, Arkansas, and much of Louisiana as a source of troops, supplies, and food.

Throughout the first two years of the war, the superior numbers and strength of the Union navy successfully subdue various Confederate strongholds along the river, many of which, including Memphis, are not suitable for a strong military defense.

Once Federal forces become ensconced in Memphis, efforts are made to seal off the southern leg of the river. In April 1862, a stunning blow is delivered to Confederate hopes when Admiral David Farragut captures the crucial port city of New Orleans. In the process, Farragut destroys the fledgling Confederate naval fleet stationed there. Confident that his gunboats and oceangoing warships can subdue Vicksburg on their own, Farragut sails northward. Confronting the garrison at Vicksburg, Farragut’s officers make loud, blusterous demands that the city avoid certain destruction and simply surrender. But the Confederate commander there, General Martin Luther Smith, understands the strength of his position. Though Farragut shells the town, Smith does not yield. In late May 1862, a frustrated Farragut concedes that his forces cannot complete the task alone, and he returns to New Orleans. But the mouth of the river is now firmly in Federal hands, and so Vicksburg becomes the last significant Confederate stronghold between Memphis and New Orleans, what most Federal strategists realize will be the toughest nut to crack along the entire length of the river.

At roughly the same time as Farragut’s gunboats are making their efforts at opening the river, far to the north, Union general Ulysses Grant embarks on what becomes a bloody yet successful campaign to wrest control of the western half of Tennessee from Confederate forces. That campaign, which concludes with the Battle of Shiloh, opens the door for Federal armies to drive hard into Mississippi and Alabama, with the goal of capturing valuable railroad hubs and slicing the Confederacy into pieces. But Grant’s superior, Henry Halleck, is not a man who recognizes opportunity. After his victory at Shiloh, Halleck vacillates, and thus he misses the opportunity to destroy a sizable army under Pierre Beauregard that is entrenched around the rail center of Corinth, Mississippi. When the Confederates escape Corinth, the entire face of the war in the West changes. Disgusted with Beauregard’s failure to prevail at Shiloh, Jefferson Davis removes Beauregard from command and replaces him with Braxton Bragg. But Bragg’s various campaigns are ineffective, and Davis knows he has to fill that command with someone more capable of inspiring his troops and defeating the enemy.

From the opening weeks of the war, Confederate general Joseph Johnston has openly feuded with Jefferson Davis. They have clashes of ego as well as policy, Johnston never accepting that Davis’s presidency gives him legitimate control over how the war will actually be fought. Johnston has proven himself a capable battlefield commander at the First Battle of Manassas (Bull Run), and in subsequent actions on the Virginia peninsula. By his lofty rank as full general, Johnston is entitled to a sizable command, and so, despite their hostility, Davis acquiesces. Johnston is named to fill the vacancy created by the death of Albert Sidney Johnston, who is killed in battle at Shiloh. His authority now spreads over the entire department west of the Appalachians, all the way to the Mississippi River. As Bragg’s superior, Johnston keeps his focus primarily on Tennessee, as Bragg struggles against Federal

forces in a series of battles from Perryville, Kentucky, down through Stones River, near Chattanooga. By the spring of 1863, aided by the exceptional abilities of cavalrymen John Hunt Morgan and Nathan Bedford Forrest, Johnston’s command in Tennessee settles into something of a stalemate with a Federal army commanded by William Rosecrans. But Johnston must deal with a new crisis more to his west. Realizing that Federal efforts are being directed more and more toward securing the Mississippi River, Johnston shifts his attention to the state of Mississippi. There his subordinate is another man Johnston finds utterly disagreeable: General John Pemberton. Pemberton commands the Confederate Department of Mississippi and thus is in control of the fortification efforts at Vicksburg. Pemberton, who is a close friend of Jefferson Davis, receives orders directly from Davis that Vicksburg must be held at all costs. It is a strategy completely at odds with Johnston’s own focus on Tennessee, and it puts Pemberton squarely in the middle of the Johnston-Davis feud. Backed by the authority of the orders he receives from his president, Pemberton continues to fortify and arm the earthworks and river batteries at Vicksburg. Pemberton becomes increasingly confident his defenses will prevail in the event that the Federal army and navy attempt any direct assault against the city.

In July 1862, Federal general Henry Halleck is called to Washington to assume the position of general in chief of the Federal forces. The choice is a wise one, but not for reasons Halleck might appreciate. In the various campaigns in the West, Halleck has proven to be an able administrator, but no one believes him to be the kind of battlefield commander the Union must have. Though the Federal armies in the West have been mostly victorious, capturing the important hub of Nashville as well as Memphis, and preventing new Confederate incursions into Kentucky, the war seems no closer to being decided. In October 1862, Lincoln promotes Ulysses Grant to overall command of the Federal armies along the Mississippi. Though intensely disliked by Halleck, Grant has considerably exceeded the expectations of his critics in Washington, and in his own command. While under Halleck, Grant notches significant victories in Tennessee, including the bloody horror at Shiloh. Grant understands the value of the Mississippi River, and with cooperation from the Federal navy, he believes the war’s end can be hastened considerably by slicing the Confederacy in two. Appreciating that a direct assault against Vicksburg could be far more costly than Lincoln will accept, Grant maps out strategies to secure the city with as little loss of life as possible. Upriver, north of Vicksburg, the Federal naval forces are under the command of Commodore (later Admiral) David Dixon Porter, who agrees with Grant’s new strategy that any attempt to capture Vicksburg must come from the north. As had happened in Grant’s successful capture of Forts Henry and Donelson in early 1862, Grant understands the value of cooperating with the navy.