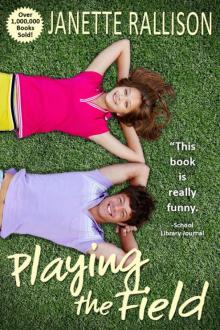

Playing the Field

Janette Rallison

Playing the Field

By Janette Rallison

Copyright 2011 Janette Rallison

Other titles by Janette Rallison

Deep Blue Eyes and Other Teenage Hazards

All’s Fair in Love, War, and High School

Life, Love, and the Pursuit of Free Throws

Fame, Glory, and Other Things on my To Do List

It’s a Mall World After All

Revenge of the Cheerleaders

How to Take The Ex Out of Ex-boyfriend

Just One Wish

My Fair Godmother

My Unfair Godmother

My Double Life

Slayers (under pen name CJ Hill)

Smashwords Edition, License Notes

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to Smashwords.com and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

Chapter 1

Mrs. Swenson was one of those teachers who probably got into the profession because she enjoyed making dour expressions. Her expression was especially dour when she gave me the news: “Mr. Conford, unless your test scores improve, and you start doing your homework, you’re going to fail algebra.” Mrs. Swenson likes to call us by our last names. I guess it sounds more dour.

When my parents found out about my algebra grade, they used my first name. Repeatedly. With increased volume every time they said it.

“McKay, why haven’t you been doing your homework?”

I had been doing it. I just hadn’t been doing it right.

“McKay, why didn’t you study for your last test?”

I did. Sort of. During the commercial breaks. I mean, it’s October for heaven's sake, and the World Series is on.

“McKay, if you can’t do the work right, you’ll have to get a tutor and pay for it with your own money.”

With the amount of allowance I got, I couldn’t afford to hire anyone who actually knew more about algebra than I did. (By the way, I didn’t actually say any of this; I just thought it. I may be failing algebra, but I’m not stupid.)

“McKay, if your grade hasn’t improved at least to a C by the end of the quarter, you’ll have to drop off the baseball team. That gives you just over a month to turn your grade around.”

My parents know how to pack a threat. Granted, at the moment I was just playing fall ball. The regular season wouldn’t start until spring, but baseball was a way of life for me, and I couldn’t imagine not playing it. Besides, this year the league was having a districtwide fall ball tournament at the end of November, and my team was sure to win. I had to play.

I don’t know why adults are so hung up on algebra, anyway. Why should I care what the letter x equals, when 4x + 7 + 8x = 43? I have my life all figured out, and it doesn’t involve algebra. I’m going to be a professional baseball player. All the math I’ll need to know is how to add runs, how to average batting scores, and of course, how to calculate interest on all of the money I’ll make. I don’t care which train reaches Philadelphia first—the one leaving from New York and traveling 55 mph. or the one leaving from DC going 40 mph. I live in Gilbert, Arizona. When I’m a professional ballplayer and do start to travel, I’m going to use a private jet.

I’ve tried to explain this to Mrs. Swenson. On the last test, when she asked one of those stupid train questions, I wrote, “Professional ballplayers let their managers worry about their travel schedules.”

Mrs. Swenson has no sense of humor. When I’m famous, I’m never going to autograph a baseball for her.

That night I sat down at the kitchen table and tried to do the next day’s assignment. I wrote 2x2 + 12x = -18 neatly on my piece of paper. Then I stared at the mysterious x for a while, hoping it would give me some hint to its identity. I tried to remember how Mrs. Swenson had explained these problems to the class, but I hadn’t been listening carefully, so I didn’t get very far.

When Mom walked by, I asked her if she could help me figure it out. She sat down next to me at the table and picked up the book. She scanned over the equations and then said, “It’s been a long time since I’ve done this type of math problem.” She tapped my pencil against the table, then wrote down some numbers. “Let’s see, I think you’re supposed to divide both sides of the equation by twelve . . . wait, that’s not it . . .” She wrote down a few more numbers, then scribbled them out.

“Just wait until they put those equations on trains and send them off to Philadelphia,” I told her.

She laid down the pencil. “Maybe your father will remember how to do this stuff.”

We looked at one another silently for a moment. Dad is the one who refuses to balance the check book because he can’t get his figures to match the bank's. He sits at the kitchen table, shaking his head at the bank statement, and insists that the bank has messed up again and computers can’t be trusted.

Mom let out a sigh. “Or maybe we really are going to have to get you a tutor.”

I slid my paper back in front of me and stared down at it with determination. “I don’t need a tutor.” My allowance doesn’t even cover the cost of decently updating my baseball card collection. The last thing I wanted was another expense. “I’ll call Tony and see if he knows how to do this.”

Mom raised an eyebrow. Tony is my best friend, but not the best at algebra. “Isn’t there someone else in your class you could ask?”

“I’ll ask Tony first.”

“Well, don’t spend too long on the phone. Remember, you don’t do anything with friends until your homework is done.”

“I know, I know.” I picked up my math book and trudged over to the phone. I bet Cal Ripkin Jr.’s mother had never given him these types of lectures when he was growing up.

Tony tried to explain the assignment to me, but it still didn’t make a lot of sense. I just couldn’t get some of the equations to work out. Instead of my trains meeting anywhere, I think they both got derailed in hideous wrecks.

My dad wasn’t much more help when he got home. Before bed he looked over my algebra problems, but it was only a symbolic gesture. It was because my mom made him. He held my paper up and got a studious look on his face. “Well. Yes. I see. Very interesting.” He put the paper down and nodded. “It’s nice to know some things never change. After all these years we’re still searching for the meaning of x.”

My mom glared at him, but he ignored her and leaned closer to me. “This is exactly the reason I became a plumber.”

Mom said, “Bill, you’re not helping.”

“Well, I would if he ever brought home assignments about installing water lines.”

In a lower tone Mom told him, “United we stand, divided we get kid-sized footprints on our faces.”

“Uh, right,” Dad said. Then he patted my shoulder. “Do your algebra, go to college, and become an aerospace engineer.”

Mom rolled her eyes. “If you’re not being serious with McKay now, how do you expect him to take us seriously when we tell him he has to pass algebra or quit baseball?”

Dad shrugged. “I told him to do his algebra. What’s not serious about that?”

“I think I understand it now,” I said because I hate it when my parents fight.

Mom looked at me skeptically. “You understand it now?”

“Yeah. Tony did a good job of explaining it to me. See. I finished all of the problems.” I picked up my paper and showed it to her.

She looked it over. “X equals 5.342? Shouldn’t x be a whole number like 7 or 1

2 or something?”

“Not necessarily,” I said.

How could she argue the point? After all, she didn’t know how to do the problems any more than I did.

She handed me back the paper. “All right.”

“See,” Dad said. “McKay is on his way to engineering school right now.”

Mom didn’t say anything more and left the kitchen.

Dad watched her leave. “I don’t think she likes engineers. Maybe you’d better become a brain surgeon instead.”

* * *

The next day at school when we went over the assignment in class, I got thirteen out of twenty right. That’s only sixty-five percent. I may not be great at algebra, but I’ve been figuring out percentages since I could read the back of a baseball card. Sixty-five percent was a D. Not exactly the kind of grade that would get me into medical school or keep me on the baseball team.

I felt sick for the rest of class. This time I’d really tried to do the homework, and I had still failed. All through lunch I kept saying, “I’m doomed. My baseball career is over.”

“No, it’s not,” Tony said. “You’ll get a tutor, and you’ll be fine.”

“I’m doomed, and my allowance will be gone,” I said.

“Maybe you could get someone at school to help you for free.”

“You helped me, and I only got twelve problems right.”

“Someone who’s better at math than I am.” Tony nodded toward the other side of the cafeteria where Serena Kimball sat.

Serena was good at math. In fact, Serena was good at everything. She was not only a straight-A student, but she was also the vice president of the eighth grade. Every year, while the teachers looked on in admiration, she played a piano concerto for the school talent show. In all the years I’d gone to school with her, I’d never once seen her long brown hair out of place.

“Right,” I said. “I’ll just waltz up to her and ask her if she’d like to come home with me and run some equations.”

“You could at least talk to her. You know, be friendly. Chat about things. Then when you mention you’re having a hard time with your math, if she likes you, she’ll volunteer to help you.”

“If she likes me?” I asked. “Why would she like me?”

“Why not?” Tony said. “If you tried, you could be—” He waved his hand over me like he was performing a magic trick. “Irresistible.”

I picked up my empty sandwich bag, crumpled it up, and threw it at him.

Tony had shown an increased interest in girls since we’d entered the eighth grade, but I still thought of them as odd creatures who couldn’t throw a ball the right way and always went to the bathroom in packs. Oh sure, there had been Stephanie Morris in kindergarten—we held hands during recess, and she told me she wanted to marry me. But after a couple of weeks of walking around like a small paper-doll chain, she said she’d decided to marry Randall Parker instead. No explanation. She led Randall around the playground for the next few weeks until she got tired of him, and then she started holding hands with Bobby Friedman.

That’s when I decided girls were more trouble than they were worth.

Still, I looked over at Serena. She was leaning across the table and telling her friend Rachel something. Both of their faces were animated and laughing. The end of Serena’s hair brushed against the table, and her face tilted sideways like she was about to tell Rachel a secret. I tried to imagine Serena sitting at my kitchen table, talking and laughing like that. Somehow it just didn’t seem likely.

Tony nudged me again. “Serena would be tons better than a paid tutor. Don’t you remember that tutor my sister got for her French class? It was some college student who spit when he talked and smelled funny. You don’t want to pay some guy to come over to your house and spit at you, do you?” He nodded toward Serena again. “Trust me, Serena is the way to go. You just have to think of some casual way to talk to her.”

“Like what?”

“You know, go up to her and say something.”

I looked from Serena back to Tony. “Like what?”

Tony wadded up his lunch sack and made a hook shot into the garbage can. “Don’t you know anything about girls?” When I looked at him blankly, he said, “It’s a game. The next best game after baseball. Only instead of a bat to get on base, you use your words and a Hollywood smile.”

I gave him my most skeptical look.

“Watch a master at work. I’m about to turn on the old Manetti charm.”

Ever since Tony had noticed girls, he’d been drawing upon his Italian heritage to help him radiate charm. He was also working on what he called a “cool walk.” It was sort of a cross between a rooster strut and a cowboy swagger -although sometimes, when he didn’t coordinate it right, it looked like he had something stuck on the bottom of his shoes, and he was trying to scrape it off. Now he walked up to Serena’s table doing the cool walk, and his strut and his swagger were almost perfectly timed. I followed him with my hands shoved into my pockets.

“Hi Rachel. Hi Serena.” He stopped a couple of feet away from them. “What are you guys doing?”

Rachel and Serena glanced at each other, then looked back at us with somewhat puzzled expressions. “We’re eating lunch,” Rachel said.

“Right,” Tony said. “We just finished.”

“Oh,” Serena said.

I gulped and swallowed and mostly looked at Serena’s shoes.

“The lunch was pretty good today,” Tony said.

“Oh really?” Rachel asked. “We brought sack lunches.”

So had we. I was glad the girls didn’t know this little fact, as they would have thought we were total idiots. As it was now, we might be able to escape this situation with the girls only thinking we were partial idiots.

“Yeah,” Tony said. “Lunch was good.”

The girls nodded at us with the same patronizing stare you use when you’re talking to four-year-olds.

“I guess we’ll be going now,” Tony said.

“Okay,” Rachel said.

As we turned and walked to the door, I could hear the girls erupt into giggles. I was glad my back was to them so they couldn’t see my face turn red. I shook my head at Tony. “That was a master at work?”

“It was a start,” Tony said.

“I think it was a strikeout.”

Tony pushed the cafeteria door open with more force than he needed to. “It was breaking the ice. Now it will be easier to talk to them next time.”

“Next time?” Even though we were out of the cafeteria, I could still hear Serena and Rachel’s laughter in my mind. I shook my head again and walked a little faster. “I think I’d rather pay all of my allowance to have some funny-smelling college student come over and spit at me.”

Chapter 2

After school, on the days we had baseball practice, I always walked home with Tony. His dad then drove us to the baseball field for practice. Mr. Manetti was the coach of the Gilbert Coyotes, the best team in the East Valley league; that’s how Tony and I originally became friends. We were on the same team in fourth grade and have played ball together ever since. Tony plays third base. I’m on second. We have our system down pat. I can field a ball and deliver it to Tony before the base runners even know where it's at. We call the space between second and third “no-man's land,” and we let no man cross it without feeling our wrath.

Tony’s dad is a real estate agen, but I think his real passion is baseball. He was an all-star in college and even had an offer from the Angels to play on their farm team, but he decided realty was a more stable profession so he’d followed that instead. Sometimes I wondered if he regretted the decision. For someone who’d rather be selling houses than playing ball, he spent an awful lot of time on the baseball diamond.

As we were fixing ourselves a snack in the kitchen, Tony’s older sister, Jenna, came in and sat down at the table. Her dark hair was twisted up in curlers, and she held her head perfectly straight so as not to jiggle them. She opened a bottle

of fingernail polish and began painting her nails light purple. In between painting them, she blew on them.

After she was done with one hand, she glanced over at Tony. “I’m seeing Adam tonight. I’ll need your help again.”

Tony and I had just finished off half a bag of potato chips, and now he grabbed the peanut butter from the cupboard. “I’m busy eating.”

“You can talk and eat at the same time,” she said. “You do it all of the time.”

Tony opened a package of bread and handed me a couple of pieces. “Adam is into baseball,” he told me. “So now Jenna wants to be an expert.”

She held up her hands and examined her nails. “How complicated can it be? You play it all of the time.”

Tony ignored her and got the jam from the refrigerator. Jenna turned to me. “You’re a walking baseball encyclopedia like my brother. You tell me something.”

“Like what?”

“Like who was the best-ever pitcher?”

“Cy Young,” I said.

“Nolan Ryan,” Tony said.

“Make up your minds and tell me why.”

“His pitching record,” I said.

“Because he throws with style,” Tony said.

Jenna shook her head. “Are we talking about Young or Ryan?”

“Yes,” we both answered at once.

“Oh, never mind,” Jenna sighed dramatically. “Tell me about both of them.”

We gave her statistics for both Young and Ryan, and she repeated them as though she were trying to memorize a foreign language.

Tony finished off one sandwich, then got out bread to make another. “How could you have lived with Dad and me for so long and know so little about baseball?”

“It’s been hard,” she said, “but I’ve gotten pretty good at tuning the two of you out.”

“Thanks,” Tony said.

Jenna shrugged. “Well, I can’t help it if I don’t like baseball. I mean you hit a ball with a stick. How interesting is that?”

Tony gave her a long look. “Why don’t you just give up now and tell Adam you know nothing about the sport?”