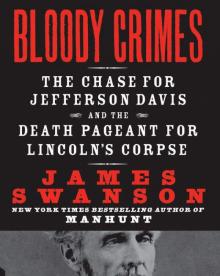

Bloody Crimes: The Funeral of Abraham Lincoln and the Chase for Jefferson Davis

James L. Swanson

Bloody Crimes

The Chase for Jefferson Davis and the Death Pageant for Lincoln’s Corpse

James L. Swanson

In memory of my mother, Dianne M. Swanson (1931–2008), who looked forward to this book but had no chance to read it.

In remembrance of John Hope Franklin (1915–2009), with gratitude for three decades of teaching, counsel, and friendship, and with fond memories of University of Chicago days.

Table of Contents

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

INTRODUCTION

PROLOGUE

CHAPTER ONE “Flitting Shadows”

CHAPTER TWO “In the Days of Our Youth”

CHAPTER THREE “Unconquerable Hearts”

CHAPTER FOUR “Borne by Loving Hands”

CHAPTER FIVE “The Body of the President Embalmed!”

CHAPTER SIX “We Shall See and Know Our Friends in Heaven”

CHAPTER SEVEN “The Cause Is Not Yet Dead”

CHAPTER EIGHT “He Is Named for You”

CHAPTER NINE “ Coffin That Slowly Passes”

CHAPTER TEN “By God, You Are the Men We Are Looking For”

CHAPTER ELEVEN “Living in a Tomb”

CHAPTER TWELVE “The Shadow of the Confederacy”

EPILOGUE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

NOTES

INDEX

Acknowledgments

Also By James L. Swanson

Copyright

About the Publisher

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

1. “Bloody Crimes” carte de visite of Columbia and her eagle xiii

2. Senator Jefferson Davis on the eve of the Civil War 4

3. Fall of Richmond paper flag 35

4. Currier & Ives print of Richmond in flames 40

5. Abraham Lincoln oil portrait, as he appeared in 1865 43

6. The Petersen House 104

7. Sketch of Lincoln on his deathbed 112

8. The empty bed, just after Lincoln died 128

9. Bloody pillow 129

10. “The President Is Dead” broadside 132

11. Diagram of the bullet’s path through Lincoln’s brain 134

12. The bullet that killed Lincoln 135

13. Allegorical print of Booth trapped inside the bullet 137

14. Portrait engraving of George Harrington 142

15. Invitation to Lincoln’s funeral 187

16. “Post Office Department” silk ribbon, April 19 funeral 190

17. Lincoln’s hearse, Washington, D.C. 191

18. Photograph of General E. D. Townsend 203

19. War Department pass for Lincoln funeral train 207

20. Lincoln’s funeral car 211

21. Silk mourning ribbon of the U.S. Military Railroad 213

22. President Lincoln’s hearse, Philadelphia 221

23. The New York funeral procession 226

24. Lincoln in coffin, New York City 230

25. Memorial arch, Sing Sing, New York 233

26. Viewing pavilion, Cleveland, Ohio 253

27. Terre Haute & Richmond Railroad timetable 260

28. Photograph of memorial arch, Chicago 264

29. Lincoln’s old law office; Springfield, May, 1865 272

30. A map of the Abraham Lincoln funeral train route 275

31. Harper’s Weekly woodcut of burial in Springfield, Illinois 283

32. The first reward poster for Jefferson Davis 297

33. A map of Jefferson Davis’s escape route 300

34. Photograph of Davis in the suit he wore at capture 310

35. $360,000 reward poster for Davis 319

36. Three caricatures depicting Davis in a dress 323

37. The raglan, shawl, and spurs Davis wore on the day of capture 328

38. Print of Davis ridiculed in prison 334

39. Sketch of Davis in his cell 335

40. Lincoln’s home draped in bunting, May 24, 1865 339

41. Davis as a caged hyena wearing a ladies’ bonnet 343

42. “The True Story…” print ridiculing Davis 346

43. Oil portrait of Jefferson Davis, ca. 1870s 360

44. Davis and family on their porch at Beauvoir, Mississippi 362

45. Oscar Wilde–inscribed photograph 364

46. Jefferson Davis late in life at Beauvoir 377

47. Davis lying in state, New Orleans, 1889 379

48. A map of the Davis funeral train route 380

49. Davis’s New Orleans funeral procession, 1889 384

50. Raleigh, North Carolina, floral display and procession, 1893 385

51. The ghosts of Willie and Abraham haunting Mary Lincoln 389

52. Photographs of porcelain Lincoln memorial obelisk 395

53. The site of Jefferson Davis’s capture, near Irwinville, Georgia 399

54. Jefferson Davis’s library at Beauvoir, Mississippi 403

INTRODUCTION

My book Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln’s Killer told the story of John Wilkes Booth’s incredible escape from the scene of his great crime at Ford’s Theatre and his run to ambush, death, and infamy at a Virginia tobacco barn. But the chase for Lincoln’s killer was not the only thrilling journey under way as the Civil War drew to a close in April 1865. While the hunt for Lincoln’s murderer transfixed the nation, two other men embarked on their own, no less dramatic, final journeys. One, Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederate States of America, was on the run, desperate to save his family, his country, and his cause. The other, Abraham Lincoln, the recently assassinated president of the United States, was bound for a different destination: home, the grave, and everlasting glory.

The title of this book has three origins—as a prophecy, a promise, and an elegy.

In October 1859, abolitionist John Brown launched his doomed raid on the U.S. arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, as a way of inciting a slave uprising. This daring but foolhardy attack, viewed as an affront to the institution of slavery, enraged the South and brought the United States closer to irrepressible conflict and civil war. Following his capture, Brown was tried and sentenced to hang. While in a Charles Town jail awaiting execution, he was allowed to keep a copy of the King James Bible. As the clock ticked down to his hanging, Brown leafed through the sacred text, searching for divinely inspired words of justification, prophecy, and warning. He dog-eared the pages most dear to him and then highlighted key passages with pen and pencil marks, including this verse from Ezekiel 7:23: “Make a chain: for the land is full of bloody crimes, and the city is full of violence.” On the morning he was hanged, on December 2, 1859, he handed to one of his jailers the last note he would ever write: “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood.”

On March 4, 1865, Abraham Lincoln delivered his second inaugural address. Although remembered today for its message of peace—“with malice toward none, with charity for all”—the speech had a dark side. In a passage often overlooked, Lincoln warned that slavery was a bloody crime that might not be expunged without the shedding of more blood: “Fondly do we hope—fervently do we pray—that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue, until all the wealth piled by the bond-man’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said ‘the judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether.’ ”

&n

bsp; Within days of Lincoln’s assassination on April 14, 1865, a Boston photographer published a fantastical carte de visite image to honor the fallen president. That was not unusual; printers, photographers, and stationers across the country produced hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of ribbons, badges, broadsides, poems, and photographs to mourn Lincoln. But the image from Boston was different, for it expressed a sentiment not of mourning but of vengeance. In

“MAKE A CHAIN, FOR THE LAND IS FULL OF BLOODY CRIMES.”

this carte de visite, a stern-faced woman, crowned and draped as Columbia, accompanied by her servant, a screaming eagle about to take flight in pursuit of its prey, keeps a vigil over a portrait of the martyred president and echoes John Brown’s old warning: “Make a chain, for the land is full of bloody crimes.” Soon, in the aftermath of the chase for Jefferson Davis and the Lincoln assassination and death pageant, manacles and chains became symbols of the spring of 1865.

Northerners believed that Jefferson Davis and the Confederacy had committed many bloody crimes, including the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, the torture, starvation, and murder of Union prisoners of war, and the battlefield slaughter of soldiers. In the South, Lincoln and his armies were seen as perpetrators, not victims, of great crimes. In the climate of these dueling accusations, the people of the Union and the Confederacy both shared a common belief and could agree upon one thing. In the spring of 1865, an era of bloody crimes had reached its climax.

The spring of 1865 was the most remarkable season in American history. It was a time to mourn the Civil War’s 620,000 dead and to bind up the nation’s wounds. It was a time to lay down arms, to tally plantations and cities that had been laid to waste, and to plant new crops. It was a time to ponder events that had come to pass and to look forward to those yet to be. It was the time of the hunt for Jefferson Davis and of the funeral pageant for Abraham Lincoln, each a martyr to his cause. And it was the time in America, wrote Walt Whitman, “when lilacs last in the door-yard bloom’d.”

PROLOGUE

WASHINGTON, D.C.

If you go there today, and walk to the most desolate corner of the cemetery, and then descend the half-hidden, decaying black slate steps, past all the other graves, down toward Rock Creek and the trees, you will find the tomb, now long empty. No sign remains that he was ever here. His name was never chiseled into the stone arch above the entry. But here, during the Civil War, in the winter of 1862, eleven-year-old Willie Lincoln, his father’s best-beloved son, was laid to rest. Here his ever-mourning father returned to visit him, to remember, and to weep. And here, the boy waited patiently behind the iron gates, locked inside the marble vault that looked no bigger than a child’s playhouse, for his father to claim him and carry him home.

That appointment, like his tiny coffin, was set in stone: March 4, 1869, the day Abraham Lincoln would complete his second term as president of the United States, leave Washington, and undertake the long railroad journey west, to Illinois. But in the spring of 1865, in the first week of April, that homecoming seemed a long way off. President Lincoln still had so much more to do.

RICHMOND, VIRGINIA

If you visit his home today, you will find no sign that he ever left. The exterior of the house looks almost exactly like it does in the Civil War–era photographs. In his private office, documents still lie on his desk, as if awaiting his signature. His presidential oil portrait hangs on a wall. Maps chart the once mighty territorial expanse of the antebellum South’s proud agricultural empire. Books line the shelves. Children’s toys lie scattered across the floor. The house is furnished as it was April 2, 1865, the day he last walked out the door, never to return.

In the spring of 1865, in the first week of April, he also had much to do. The future was uncertain. His capital city could no longer be defended and might fall to invading Union armies within days, even hours. To save his country, he had to abandon the president’s mansion and flee Richmond. He could take little with him. Soon he would leave behind almost all he loved, including his five-year-old son, Joseph, who had died in his White House in 1864 and now rested in the sacred grounds of the city’s Hollywood Cemetery, where many Confederate heroes, including General J. E. B. Stuart, were also buried. Perhaps one day Jefferson Davis would return to claim the boy, but for now, he had to go on ahead.

CHAPTER ONE

“Flitting Shadows”

On the morning of Sunday, April 2, 1865, President Jefferson Davis walked, as was his custom, from the White House of the Confederacy to St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, where Robert E. Lee and his wife worshipped and where Davis was confirmed as a member of the parish in 1861. Everything that day appeared beautiful and serene. The air smelled of spring, and the fresh green growth promised a season of new life. One of the worshippers, a young woman named Constance Cary, recalled that on this “perfect Sunday of the Southern spring, a large congregation assembled as usual at St. Paul’s.”

Richmond did not look like a city at war, but it had become a symbol of the conflict. As the capital city of the Confederate States of America, it was the seat of slavery’s and secession’s empire, one of the loveliest cities in the South, the spiritual center of Virginia’s aristocracy and of the rebellion, and, for the entire bloody Civil War that had cost the lives of more than 620,000 men, a strategic obsession in the popular imagination of the Union.

JEFFERSON DAVIS AT THE HEIGHT OF HIS POWER.

Despite Richmond’s vulnerable proximity to Washington, D.C.—the White House of the Confederacy stood less than one hundred miles from Lincoln’s Executive Mansion—the Confederate capital had defied capture. Unlike the unfortunate citizens of New Orleans, Vicksburg, Atlanta, Savannah, Mobile, and Charleston, whose homes had been besieged and prostrated, the people of Richmond had never suffered bombardment, capture, or surrender. In the spring of 1861, Yankee volunteers had naively and boastfully cried, “On to Richmond,” for it seemed, at the beginning, that victory would be so easy. Many in the North believed that Richmond would fall quickly, ending the rebellion before it could even achieve much momentum.

But four years and oceans of blood later, the fighting continued and no Yankee invaders had breached Richmond’s defenses. Not one enemy artillery shell had bombarded its stately residences, war factories, and government buildings. No blackened, burned-out ruins marred the handsome architectural streetscapes. And from the highest point in the city of the seven hills, no advancing federal armies were visible on the horizon. No, Richmond had been spared many of the horrors of war, the physical devastation and humiliating enemy occupation that had befallen many of the great cities of the South.

This morning as the Reverend Dr. Charles Minnigerode, a larger-than-life figure in Richmond society, was conducting services, a messenger entered the church. He carried a dispatch to the president that had arrived in Richmond at 10:40 A.M. It was a telegram from General Lee, bringing to the president’s church pew news of a double calamity: The Union army was approaching the city gates, and the glorious Army of Northern Virginia was powerless to stop them.

Davis described the scene: “On Sunday, the 2d of April, while I was in St. Paul’s church, General Lee’s telegram, announcing his speedy withdrawal from Petersburg, and the consequent necessity for evacuating Richmond, was handed to me.”

The telegram was not addressed to Davis, but to Confederate secretary of war John C. Breckinridge, vice president of the United States from 1857 to 1861 during James Buchanan’s administration. On March 4, 1861, Breckinridge’s fellow Kentuckian Abraham Lincoln took the oath of office as president, and he heard the new commander in chief deliver his inaugural address. “We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies,” Lincoln had said to the South that day. Now Breckinridge had received a telegram warning him that the Union army was approaching and the government would likely have to abandon the capital that very night, in less than fourteen hours.

Headquarters,

April 2, 1865

General J. C. Breckinrid

ge:

I see no prospect of doing more than holding our position here till night. I am not certain that I can do that. If I can I shall withdraw tonight north of the Appomattox, and if possible it will be better to withdraw the whole line tonight from James River. Brigades on Hatcher’s Run are cut off from us. Enemy have broken through our lines and intercepted between us and them, and there is no bridge over which they can cross the Appomattox this side of Goode’s or Beaver’s, which are not very far from the Danville Railroad. Our only chance, then of concentrating our forces, is to do so near Danville Railroad, which I shall endeavor to do at once. I advise that all preparation be made for leaving Richmond tonight. I will advise you later, according to circumstances.

R. E. Lee

On reading the telegram, Davis did not panic, though the distressing news drained the color from his face. Constance Cary, who would later marry the Confederate president’s private secretary, Colonel Burton Harrison, watched Davis while he read the telegram: “I happened to sit in the rear of the President’s pew, so near that I plainly saw the sort of gray pallor that came upon his face as he read a scrap of paper thrust into his hand by a messenger hurrying up the middle aisle. With stern set lips and his usual quick military tread, he left the church.”

Davis knew his departure would attract attention, but he noted, “the people of Richmond had been too long beleaguered, had known me too often to receive notes of threatened attacks, and the congregation of St. Paul’s was too refined, to make a scene at anticipated danger.”

“Before dismissing the congregation,” Cary remembered, “the rector announced to them that General Ewell had summoned the local forces to meet for the defence of the city at three in the afternoon…a sick apprehension filled all hearts.”

Worshippers, including Miss Cary, gathered in front of St. Paul’s: “On the sidewalk outside the church, we plunged at once into the great stir of evacuation, preluding the beginning of a new era. As if by a flash of electricity, Richmond knew that on the morrow her streets would be crowded by her captors, her rulers fled, her government dispersed into thin air, her high hopes crushed to earth. There was little discussion of events. People meeting each other would exchange silent hand grasps and pass on. I saw many pale faces, some trembling lips, but in all that day I heard no expression of a weakling fear.”