Maisie Dobbs

Jacqueline Winspear

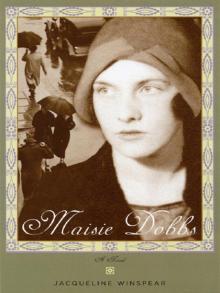

Maisie Dobbs

Maisie Dobbs

A Novel

JACQUELINE WINSPEAR

The excerpt from “Disabled” by Wilfred Owen, from The Collected Poems of

Wilfred Owen, copyright © 1963 by Chatto & Windus, Ltd. is reprinted

by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp.

Copyright © 2003 by Jacqueline Winspear

Published by

Soho Press, Inc.

853 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

is available in the office of the publisher.

ISBN 1-56947-330-7

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book is dedicated to the memory of

my paternal grandfather and my maternal grandmother

JOHN “JACK” WINSPEAR sustained serious leg wounds during the Battle of the Somme in July 1916. Following convalescence, he returned to his work as a costermonger in southeast London.

CLARA FRANCES CLARK, née Atterbury, was a munitions worker at the Woolwich Arsenal during the First World War. She was partially blinded in an explosion that killed several girls working in the same section alongside her. Clara later married and became the mother of ten children.

Now, he will spend a few sick years in institutes,

And do what things the rules consider wise,

And take whatever pity they may dole.

Tonight he noticed how the women’s eyes

Passed from him to the strong men that were whole.

How cold and late it is! Why don’t they come

And put him to bed? Why don’t they come?

Final verse “Disabled,” by Wilfred Owen. It was drafted at Craiglockhart, a hospital for shell-shocked officers, in October 1917.Owen was killed on November 4, 1918, just one week before the armistice.

Contents

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY - ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY - TWO

CHAPTER TWENTY - THREE

CHAPTER TWENTY - FOUR

CHAPTER TWENTY - FIVE

CHAPTER TWENTY - SIX

CHAPTER TWENTY - SEVEN

CHAPTER TWENTY - EIGHT

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE

CHAPTER THIRTY

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

SPRING 1929

CHAPTER ONE

Even if she hadn’t been the last person to walk through the turnstile at Warren Street tube station, Jack Barker would have noticed the tall, slender woman in the navy blue, thigh-length jacket with a matching pleated skirt short enough to reveal a well-turned ankle. She had what his old mother would have called “bearing.”A way of walking, with her shoulders back and head held high, as she pulled on her black gloves while managing to hold on to a somewhat battered black document case.

“Old money,”muttered Jack to himself.“Stuck-up piece of nonsense.” Jack expected the woman to pass him by, so he stamped his feet in a vain attempt to banish the sharp needles of cold creeping up through his hobnailed boots. He fanned a half dozen copies of the Daily Express over one arm, anticipating a taxi-cab screeching to a halt and a hand reaching out with the requisite coins.

“Oh, stop—may I have an Express please, love?” appealed a voice as smooth as spooned treacle.

The newspaper vendor looked up slowly, straight into eyes the color of midnight in summer, an intense shade that seemed to him to be darker than blue. She held out her money.

“O’ course, Miss, ’ere you are. Bit nippy this morning, innit?”

She smiled, and as she took the paper from him before turning to walk away, she replied,“Not half. It’s brass monkey weather; better get yourself a nice cuppa before too long.”

Jack couldn’t have told you why he watched the woman walk all the way down Warren Street toward Fitzroy Square. But he did know one thing: She might have bearing, but from the familiar way she spoke to him, she certainly wasn’t from old money.

At the end of Warren Street, Maisie Dobbs stopped in front of the black front door of a somewhat rundown Georgian terraced house, tucked the Daily Express under her left arm, carefully opened her document case, and took out an envelope containing a letter from her landlord and two keys. The letter instructed her to give the outside door a good shove after turning the key in the lock, to light the gas lamp at the base of the stairs carefully, to mind the top step of the first flight of stairs—which needed to be looked at—and to remember to lock her own door before leaving in the evening. The letter also told her that Billy Beale, the caretaker, would put up her nameplate on the outside door if she liked or, it suggested, perhaps she would prefer to remain anonymous.

Maisie grinned. I need the business, she said to herself. I’m not here to remain anonymous.

Maisie suspected that Mr. Sharp, the landlord, was unlikely to live up to his name, and that he would pose questions with obvious answers each time they met. However, his directions were apt: The door did indeed need a shove, but the gas lamp, once lit, hardly dented the musky darkness of the stairwell. Clearly there were some things that needed to be changed, but all in good time. For the moment Maisie had work to do, even if she had no actual cases to work on.

Minding the top step, Maisie turned right on the landing and headed straight for the brown painted door on the left, the one with a frosted glass window and a To Let sign hanging from the doorknob. She removed the sign, put the key into the lock, opened the door, and took a deep breath before stepping into her new office. It was a single room with a gas fire, a gas lamp on each wall, and one sash window with a view of the building across the street and the rooftops beyond. There was an oak desk with a matching chair of dubious stability, and an old filing cabinet to the right of the window.

Lady Rowan Compton, her patron and former employer, had been correct;Warren Street wasn’t a particularly salubrious area. But if she played her cards right, Maisie could afford the rent and have some money left over from the sum she had allowed herself to take from her savings. She didn’t want a fancy office, but she didn’t want an out-and-out dump either. No, she wanted something in the middle, something for everyone, something central, but then again not in the thick of things. Maisie felt a certain comfort in this small corner of Bloomsbury. They said that you could sit down to tea with just about anyone around Fitzroy Square, and dine with a countess and a carpenter at the same table, with both of them at ease in the company. Yes, Warren Street would be good for now. The tricky thing was going to be the nameplate. She still hadn’t solved the problem of the nameplate.

As Lady Rowan had asked,“So, my dear, what will you call yourself? I mean, we all know what you do, but what will be your trade name? You can hardly state the obvious. ‘Finds missing people, dead or alive, even when it’s themselves they are looking for’ really doesn’t cut the mustard. We have to think of something succinct, something that draws upon your unique talents.”

“I was thinking of ‘Discreet Investigations,’ Lady Rowan. What do you think?”

“But that doesn’t tell anyone about how you use your mind, my dear—what you actually do.”

“It’s not really my min

d I’m using, it’s other people’s. I just ask the questions.”

“Poppycock! What about ‘Discreet Cerebral Investigations’?”

Maisie smiled at Lady Rowan, raising an eyebrow in mock dismay at the older woman’s suggestion. She was at ease, seated in front of the fireplace in her former employer’s library, a fireplace she had once cleaned with the raw, housework-roughened hands of a maid in service.

“No, I’m not a brain surgeon. I’m going to think about it for a bit, Lady Rowan. I want to get it right.”

The gray-haired aristocrat leaned over and patted Maisie on the knee. “I’m sure that whatever you choose, you will do very well, my dear. Very well indeed.”

So it was that when Billy Beale, the caretaker, knocked on the door one week after Maisie moved into the Warren Street office, asking if there was a nameplate to put up at the front door, Maisie handed him a brass plate bearing the words “M. Dobbs. Trade and Personal Investigations.”

“Where do you want it, Miss? Left of the door or right of the door?”

He turned his head very slightly to one side as he addressed her. Billy was about thirty years old, just under six feet tall, muscular and strong, with hair the color of sun-burnished wheat. He seemed agile, but worked hard to disguise a limp that Maisie had noticed immediately.

“Where are the other names situated?”

“On the left, Miss, but I wouldn’t put it there if I were you.”

“Oh, and why not, Mr. Beale?”

“Billy. You can call me Billy. Well, people don’t really look to the left, do they? Not when they’re using the doorknob, which is on the right. That’s where the eyes immediately go when they walk up them steps, first to that lion’s ’ead door knocker, then to the knob, which is on the right. Best ’ave the plate on the right. That’s if you want their business.”

“Well, Mr. Beale, let’s have the plate on the right. Thank you.”

“Billy, Miss. You can call me Billy.”

Billy Beale went to fit the brass nameplate. Maisie sighed deeply and rubbed her neck at the place where worry always sat when it was making itself at home.

“Miss . . . .”

Billy poked his head around the door, tentatively knocking at the glass as he removed his flat cap.

“What is it, Mr. Beale?”

“Billy, Miss. Miss, can I have a quick word?”

“Yes, come in. What is it?”

“Miss, I wonder if I might ask a question? Personal, like.” Billy continued without waiting for an answer.“Was you a nurse? At a casualty clearing station? Outside of Bailleul?”

Maisie felt a strong stab of emotion, and instinctively put her right hand to her chest, but her demeanor and words were calm.

“Yes. Yes, I was.”

“I knew it!” said Billy, slapping his cap across his knee.“I just knew it the minute I saw those eyes. That’s all I remember, after they brought me in. Them eyes of yours, Miss. Doctor said to concentrate on looking at something while ’e worked on me leg. So I looked at your eyes, Miss. You and ’im saved my leg. Full of shrapnel, but you did it, didn’t you? What was ’is name?”

For a moment, Maisie’s throat was paralyzed. Then she swallowed hard. “Simon Lynch. Captain Simon Lynch. That must be who you mean.”

“I never forgot you, Miss. Never. Saved my life, you did.”

Maisie nodded, endeavoring to keep her memories relegated to the place she had assigned them in her heart, to be taken out only when she allowed.

“Well, Miss. Anything you ever want doing, you just ’oller. I’m your man. Stroke of luck, meeting up with you again, innit? Wait till I tell the missus. You want anything done, you call me. Anything.”

“Thank you. Thank you very much. I’ll holler if I need anything.

Oh, and Mr. . . . Billy, thank you for taking care of the sign.”

Billy Beale blushed and nodded, covered his burnished hair with his cap, and left the office.

Lucky, thought Maisie. Except for the war, I’ve had a lucky life so far. She sat down on the dubious oak chair, slipped off her shoes and rubbed at her feet. Feet that still felt the cold and wet and filth and blood of France. Feet that hadn’t felt warm in twelve years, since 1917.

She remembered Simon, in another life, it seemed now, sitting under a tree on the South Downs in Sussex. They had been on leave at the same time, not a miracle of course, but difficult to arrange, unless you had connections where connections counted. It was a warm day, but not one that took them entirely away from the fighting, for they could still hear the deep echo of battlefield cannonade from the other side of the English Channel, a menacing sound not diminished by the intervening expanse of land and sea. Maisie had complained then that the damp of France would never leave her, and Simon, smiling, had pulled off her walking shoes to rub warmth into her feet.

“Goodness, woman, how can anyone be that cold and not be dead?”

They both laughed, and then fell silent. Death, in such times, was not a laughing matter.

CHAPTER TWO

The small office had changed in the thirty days since Maisie had taken up occupancy. The desk had been moved and was now positioned at an angle to the broad sash window, so that from her chair Maisie could look up and out over the rooftops as she worked. A very sophisticated black telephone sat on top of the desk, at the insistence of Lady Rowan, who maintained that “No one, simply no one, can expect to do business without a telephone. It is essential, positively essential.”As far as Maisie was concerned, what was essential was that the trilling of its authoritative ring be heard a bit more often. Billy Beale had also taken to suggesting improvements lately.

“Can’t have folk up ’ere for business without offering ’em a cuppa the ol’ char, can you, Miss? Let me open up that cupboard, put in a burner, and away you go. Bob’s yer uncle, all the facilities for tea. What d’you think, Miss? I can nip down the road to my mate’s carpentry shop for the extra wood, and run the gas along ’ere for you. No trouble.”

“Lovely, Billy. That would be lovely.”

Maisie sighed. It seemed that everyone else knew what would be best for her. Of course their hearts were in the right place, but what she needed most now was some clients.

“Shall I advance you the money for supplies, Billy?”

“No money needed,” said Billy, winking and tapping the side of his nose with his forefinger.“Nod’s as good as a wink to a blind ’orse, if you know what I mean, Miss.”

Maisie raised an eyebrow and allowed herself a grin. “I know exactly what that saying means, Billy: What I don’t see, I shouldn’t worry about.”

“You got it, Miss. Leave it to me. Two shakes of a lamb’s tail, and you’ll be ready to receive your visitors in style.”

Billy replaced his cap, put a forefinger to the peak to gesture his departure, and closed the door behind him. Leaning back in her chair, Maisie rubbed at tired eyes and looked over the late afternoon rooftops. She watched as the sun drifted away to warm the shores of another continent, leaving behind a rose tint to bathe London at the end of a long day.

Looking again at her handwritten notes, Maisie continued rereading a draft of the report she was in the midst of preparing. The case in question was minor, but Maisie had learned the value of detailed note taking from Maurice Blanche. During her apprenticeship with him, he had been insistent that nothing was to be left to memory, no stone to remain unturned, and no small observation uncataloged. Everything, absolutely everything, right down to the color of the shoes the subject wore on the day in question, must be noted. The weather must be described, the direction of the wind, the flowers in bloom, the food eaten. Everything must be described and preserved. “You must write it down, absolutely and in its entirety, write it down,” instructed her mentor. In fact, Maisie thought that if she had a shilling for every time she heard the words,“absolutely, and in its entirety,” she would never have to work again.

Maisie rubbed her neck once more, closed the folder on her

desk, and stretched her arms above her head. The doorbell’s deep clattering ring broke the silence. At first Maisie thought that someone had pulled the bell handle in error. There had been few rings since Billy installed the new device, which sounded in Maisie’s office. Despite the fact that Maisie had worked with Maurice Blanche and had taken over his practice when he retired at the age of seventy-six, establishing her name independent of Maurice was proving to be a challenge indeed. The bell rang again.

Maisie pressed her skirt with her hands, patted her head to tame any stray tendrils of hair, and hurried downstairs to the door.

“Good. . . .” The man hesitated, then consulted a watch that he drew from his waistcoat pocket, as if to ascertain the accurate greeting for the time of day. “Good evening. My name is Davenham, Christopher Davenham. I’m here to see Mr. Dobbs. I have no appointment, but was assured that he would see me.”

He was tall, about six feet two inches by Maisie’s estimate. Fine tweed suit, hat taken off to greet her at just the right moment, but repositioned quickly. Good leather shoes, probably buffed to a shine by his manservant. The Times was rolled up under one arm, but with a sheet or two of writing paper coiled inside and just visible. His own notes, thought Maisie. His jet black hair was swept back and oiled, and his moustache neatly trimmed. Christopher Davenham was about forty-two or forty-three. Only seconds had passed since his introduction, but Maisie had him down. This one had not been a soldier. In a protected profession, she suspected.

“Come this way, Mr. Davenham. There are no appointments set for this evening, so you are in luck.”

Maisie led the way up to her office, and invited Christopher Davenham to sit in the new guest chair opposite her own, the chair that had been delivered just last week by Lady Rowan’s chauffeur. Another gift to help her business along.