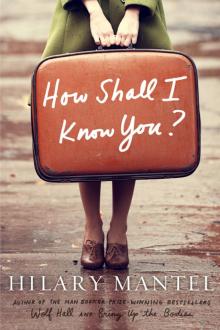

How Shall I Know You?: A Short Story

Hilary Mantel

HOW SHALL I KNOW YOU?

A STORY

HILARY MANTEL

A JOHN MACRAE BOOK

HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY

NEW YORK

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: http://us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright Notice

Also by Hilary Mantel

How Shall I Know You?: A Short Story

The Assassination of Margaret Thatcher

More from Hilary Mantel

Copyright

ALSO BY HILARY MANTEL

Beyond Black

Every Day Is Mother’s Day

Vacant Possession

Eight Months on Ghazzah Street

Fludd

A Place of Greater Safety

A Change of Climate

An Experiment in Love

The Giant, O’Brien

Learning to Talk

Wolf Hall

Bring Up the Bodies

The Assassination of Margaret Thatcher

NONFICTION

Giving Up the Ghost

One summer at the fag end of the nineties, I had to go out of London to talk to a literary society, of the sort that must have been old-fashioned when the previous century closed. When the day came, I wondered why I’d agreed to it; but yes is easier than no, and of course when you make a promise you think the time will never arrive: that there will be a nuclear holocaust, or something else diverting. Besides, I had a sentimental yearning for the days of self-improvement; they were founded, these reading clubs, by master drapers and their shopgirl wives; by poetasting engineers, and uxorious physicians with long winter evenings to pass. Who keeps them going these days?

I was leading at the time an itinerant life, struggling with the biography of a subject I’d come to dislike. For two or three years I’d been trapped into a thankless cycle of picking up after myself, gathering in what I’d already gathered, feeding it onto computer disks that periodically erased themselves in the night. And I was forever on the move with my card indexes and my paper clips, and my cheap notebooks with their porous, blotchy pages. It was easy to lose these books, and I left them in black cabs or in the overhead racks of trains, or swept them away with bundles of unread newspapers from the weekends. Sometimes it seemed I’d be forever compelled to retrace my own steps, between Euston Road and the newspaper collections, which in those days were still in Colindale; between the rain-soaked Dublin suburb where my subject had first seen the light and the northern manufacturing town where—ten years after he ceased to be use or ornament—he cut his throat in a bathroom of a railway hotel. “Accident,” the coroner said, but there’s a strong suspicion of a cover-up; for a man with a full beard, he must have been shaving very energetically.

***

I WAS LOST and drifting that year, I don’t deny it. And as my bag was always packed, there was no reason to turn down the literary society. They would ask me, they said, to give their members a snappy summary of my researches, to refer briefly to my three short early novels, and then answer questions from the floor: after which, they said, there would be a Vote of Thanks. (I found the capitals unsettling.) They would offer a modest fee—they said it—and lodge me for bed and breakfast at Rosemount, which was quietly situated, and of which, they said enticingly, I would find a photograph enclosed.

This photograph came in the secretary’s first letter, double-spaced on small blue paper, produced by a typewriter with a jumping h. I took Rosemount to the light and looked at it. There was a suspicion of a Tudor gable, a bay window, a Virginia creeper—but the overall impression was of blurring, a running of pigment and a greasiness at the edges, as if Rosemount might be one of those ghost houses that sometimes appear at a bend in the road, only to melt away as the traveler limps up the path.

So I was not surprised when another blue letter came, hiccupping in the same way, to say that Rosemount was closing for refurbishments and they would be obliged to use Eccles House, convenient for the venue and they understood quite reputable. Again, they enclosed a photograph: Eccles House was part of a long white terrace, four stories high, with two surprised attic windows. I was touched that they felt they ought to illustrate the accommodation in this way. I never cared where I stayed as long as it was clean and warm. I had often, of course, stayed in places that were neither. The winter before there had been a guesthouse in a suburb of Leicester, with a smell so repellent that when I woke at dawn I was unable to stay in my room for longer than it took me to dress, and I found myself, long before anyone else was awake, setting my booted feet on the slick wet pavements, tramping mile after mile down rows of semidetached houses of blackening pebbledash, where the dustbins had wheels but the cars were stacked on bricks; where I turned at the end of each street, and crossed, and retrod my tracks, while behind thin curtains East Midlanders turned and muttered in their sleep, a hundred and a hundred then a hundred couples more.

In Madrid, by contrast, my publishers had put me in a hotel suite that consisted of four small dark paneled rooms. They had sent me an opulent, unwieldy, scented bouquet, great wheels of flowers with woody stems. The concierge brought me heavy vases of a grayish glass, slippery in my hands, and I edged them freighted with blooms onto every polished surface; I stumbled from room to room, coffinned against the brown paneling, forlorn, strange, under a pall of pollen, like a person trying to break out from her own funeral. And in Berlin, the desk clerk had handed me a key with the words “I hope your nerves are strong.”

THE WEEK BEFORE the engagement, my health was not good. There was a continuous airy shimmer in my field of vision, just to the left of my head, as if an angel were trying to appear. My appetite failed, and my dreams took me to strange waterfronts and ships’ bridges, on queasy currents and strange washes of the tide. As a biographer I was more than usually inefficient; in untangling my subject’s accursed genealogy I mixed up Aunt Virginie with the one who married the Mexican, and spent a whole hour with a churning stomach, thinking that all my dates were wrong and believing that my whole Chapter Two would have to be reworked. The day before I was due to travel east I simply gave up on the whole enterprise, and lay on my bed with my eyes shut tight. I felt not so much a melancholy, as a kind of general insufficiency. I seemed to be pining for those three short early novels, and their brittle personnel. I felt a wish to be fictionalized.

My journey was uneventful. Mr. Simister, the secretary, met me at the station. How shall I know you? he had said on the telephone. Do you look like the photograph on your book jackets? Authors, I find, seldom do. He giggled after saying this, as if it were edgy wit of a high order. I had considered: a short pause on the line had made him ask, Still there? I am the same, I said. They are not a bad likeness, only I am older now, of course, thinner in the face, my hair is much shorter and a different color, and I seldom smile in quite that way. I see, he said.

“Mr. Simister,” I asked, “how shall I know you?”

I KNEW HIM by his harassed frown, and the copy of my first novel, A Spoiler at Noonday, which he held across his heart. He was buttoned into an overcoat; we were in June, and it had turned wintry. I had expected him to hiccup, like his typewriter.

“I think we shall have a wet one of it,” he said, as he led me to his car. It took me a little time to work my way through this syntactical oddity. Meanwhile he creaked and ratcheted car seats, tossed a

soiled evening newspaper onto the dog blanket in the back, and vaguely flapped his hand over the passenger seat as if to remove lint and dog hairs by a magic pass. “Don’t your members go out in the rain?” I said, grasping his meaning at last.

“Never know, never know,” he replied, slamming the door and shutting me in. My head turned back, automatically, the way I had come. As, these days, my head tends to do.

We drove for a mile or so, toward the city center. It was five-thirty, rush hour. My impression was of an arterial road, lined by sick saplings, and lorries and tankers rumbling toward the docks. There was a huge, green roundabout, of which Mr. Simister took the fifth exit, and reassured me, “Not far now.”

“Oh, good,” I said. I had to say something.

“Are you not a good traveler?” Mr. Simister said anxiously.

“I’ve been ill,” I said. “This last week.”

“I’m sorry to hear that.”

He did look sorry; perhaps he thought I would be sick on his dog blanket.

I turned away deliberately and watched the city. On this wide, straight, busy stretch, there were no real shops, just the steel-shuttered windows of small businesses. On their upper floors at smeary windows were pasted Day-Glo banners that said TAXI TAXI TAXI. It struck me as an area of free enterprise: freelance debt collectors, massage parlors, body shops and money launderers, dealers in seedy accommodation let twice and thrice, bucket shops for flights to Miami or Bangkok, and netted yards where inbred terriers snarl and cars are given a swift respray before finding a happy new owner. “Here we are.” Mr. Simister pulled up. “Like me to come in?”

“No need,” I said. I looked around me. I was miles from anywhere, traffic snarling by. It was raining now, just as Mr. Simister had said it would. “Half past six?” I asked.

“Six-thirty,” he said. “Nice time for a wash and brushup. Oh, by the way, we’re renamed now, Book Group. What do you think? Falling rolls, you see, members dead.”

“Dead? Are they?”

“Oh yes. Get in the younger end. You’re sure you wouldn’t like a hand with that bag?”

ECCLES HOUSE WAS not precisely as the photograph had suggested. Set back from the road, it seemed to grow out of a parking lot, a jumble of vehicles double-parked and crowding to the edge of the pavement. It had once been a residence of some dignity, but what I had taken to be stucco was in fact some patent substance newly glued to the front wall: it was grayish-white and crinkled, like a split-open brain, or nougat chewed by a giant.

I stood on the steps and watched Mr. Simister edge into the traffic. The rain fell harder. On the opposite side of the road there was a carpet hangar, with the legend ROOM-SIZED REMNANTS painted on a banner on its façade. A depressed-looking boy zipped into his waterproofs was padlocking it for the night. I looked up and down the road. I wondered what provision they had made for me to eat. Normally, on evenings like this, I would make some excuse—a phone call expected, a nervous stomach—and turn down the offer of “a bit of dinner.” I never want to prolong the time I spend with my hosts. I am not, in fact, a nervous woman, and the business of speaking to a hundred people or so causes me no qualms, but it is the small talk afterward that wears me down, and the twinkling jocularity, the “book-chat” that grates like a creaking hinge.

So I would sneak away; and if I had not been able to persuade the hotel to leave me some sort of supper tray, I would walk out and find a small, dark, half-empty restaurant, at the end of a high street, that would provide a dish of pasta or a fillet of sole, a half-bottle of bad wine, a diesel-oil espresso, a glass of Strega. But tonight? I would have to go along with whatever arrangement they had made for me. Because I could not eat carpets, or “personal services,” or solicit a bone from a drug dealer’s dog.

MY HAIR FLATTENED by the rain, I stepped inside, to a travelers’ stench. I was reminded at once of my visit to Leicester; but this place, Eccles House, was on a stifling scale of its own. I stood and breathed in—because one must breathe—tar of ten thousand cigarettes, fat of ten thousand breakfasts, the leaking metal seep of a thousand shaving cuts, and the horse-chestnut whiff of nocturnal emissions. Each odor, ineradicable for a decade, had burrowed into the limp chintz of the curtains and into the scarlet carpet that ran up the narrow stairs.

At once I felt my guardian angel flash, at the corner of my eye. The weakness he brought with him, the migrainous qualm, ran through my whole body. I put out the palm of my hand and rested it against the papered wall.

There seemed to be no reception desk, nowhere to sign in. Probably no point: who’d stay here, who traveled under their right name? Come to that, I didn’t travel under mine. Sometimes I got confused, what with the divorce disentanglements, and the business bank accounts, and the name under which I’d written my early novels, which happened to be the name of one of my grandmothers. You should be sure, when you start in this business, that there’s one name you can keep: one that you feel entitled to, come what may.

From somewhere—beyond a door, and another door—there was a burst of male laughter. The door swung shut; the laughter ended in a wheeze, which trailed like another odor on the air. Then a hand reached for my bag. I looked down, and saw a small girl—a girl, I mean, in her late teens: a person, diminutive and crooked, banging my bag against her thigh.

She looked up and smiled. She had a face of feral sweetness, its color yellow; her eyes were long and dark, her mouth a taut bow, her nostrils upturned as if she were scenting the wind. Her neck seemed subject to a torsion; the muscles on the right side were contracted, as if some vast punitive hand had picked her up and taken her in a grip. Her body was tiny and twisted, one hip thrust out, one leg lame, one foot trailing. I saw this as she broke away from me, lugging my bag toward the stairs.

“Let me do that.” I carry, you see, not just the notes of whatever chapter I am working on, but also my diary, and those past diaries, kept in A4 spiral notebooks, that I don’t want my current partner to read while I’m away: I think carefully about what would happen if I were to die on a journey, leaving behind me a desk stacked with ragged prose and unpunctuated research notes. My bag is therefore small but leaden, and I rushed to catch up with her, wanting to drag it from her poor hand, only to realize that the scarlet stinking stairs shot steeply upward, their risers deep enough to trip the unwary, and took a sharp twist that brought us to the first landing. “Up to the top,” she said. She turned to smile over her shoulder. Her face swiveled to a hideous angle, almost to where the back of her head had been. With a fast, crabwise scuttle, leaning on the side of her built-up shoe, she shot away toward the second floor.

She had lost me, left me behind. By that second landing, I was not in the race. As I began to climb to the third floor—the stairs now were like a ladder, and the smell was more enclosed, and had clotted in my lungs—I felt again the flash of the angel. I was short of breath, and this made me stop. “Only a few more,” she called down. I stumbled up after her.

On a dark landing, she opened one door. The room was a sliver: not even a garret, but a bit of corridor blocked off. There was a sash window that rattled, and a spiritless divan with a brown cover, and a small brown chair with a plush buttoned back, which—I saw at once—had a gray rime of dust, like navel fluff, accumulated behind each of its buttons. I felt sick, from this thought, and the climb. She turned to me, her head wobbling, her expression dubious. In the corner was a plastic tray, with a small electric kettle of yellowed plastic; yellowed wheat ears decorated it. There was a cup.

“All this is free,” she said. “It is complimentary. It is included.”

I smiled. At the same time, inclined my head, modestly, as if someone were threading an honor around my neck.

“It is in the price. You can make tea. Look.” She held up a sachet of powder. “Or coffee.”

My bag was still in her hand; and looking down, I saw that her hands were large and knuckly, and covered, like a man’s, with small unregarded cuts.

“She d

oesn’t like it,” she whispered. Her head fell forward onto her chest.

It was not resignation; it was a signal of intent. She was out of the room, she was hurtling toward the stair head, she was swarming down before I could draw breath.

My voice trailed after her. “Oh, please … really, don’t …”

She plunged ahead, and around the bend in the stairs. I followed, I reached out, but she lurched away from me. I took a big ragged breath. I didn’t want to go down, you see, if I might have to come up again. In those days I didn’t know there was something wrong with my heart. I only found it out this year.

WE WERE BACK on the ground floor. The child produced from a pocket a big bunch of keys. Again, that bilious laughter washed out, from some unseen source. The door she opened was too near this laughter, far too near for my equanimity. The room itself was identical, except that a kitchen smell was in it, deceptively sweet, as if there were a corpse in the wardrobe. She put down my bag on the threshold.

I felt I had come a long way that day, since I had crept out of my double bed, the other side occupied by a light sleeper who still seemed, sometimes, a stranger to me. I had crossed London, I had traveled east, I had been up the stairs and down. I felt myself too proximate, now, to the gusty, beery laughter of unknown men. “I’d rather …” I said. I wanted to ask her to try for an intermediate floor. Perhaps not all the rooms were empty, though? It was the other occupants I didn’t like, the thought of them, and I realized that here on the ground floor I was close to the bar, to the slamming outer door letting in the rain and the twilight, to the snarled-up traffic … She picked up my bag. “No …” I said. “Please. Please don’t. Let me …”

But she was off again, swaying at speed toward the stairs, dragging her leg after her, like an old rebuff. I heard her draw breath above me. She said, as if just to herself, “She thought it was worse.”