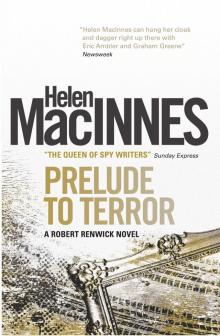

Prelude to Terror

Helen Macinnes

ALSO BY HELEN MacINNES

AND AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

Pray for a Brave Heart

Above Suspicion

Assignment in Brittany

North From Rome

Decision at Delphi

The Venetian Affair

The Salzburg Connection

Message From Málaga

While We Still Live

The Double Image

Neither Five Nor Three

Horizon

Snare of the Hunter

Agent in Place

Ride a Pale Horse

The Hidden Target (September 2013)

I and My True Love (October 2013)

Cloak of Darkness (November 2013)

Rest and Be Thankful (December 2013)

Friends and Lovers (January 2014)

Home is the Hunter (February 2014)

Prelude to Terror

Print edition ISBN: 9781781163368

E-book edition ISBN: 9781781164389

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First edition: August 2013

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

© 1978, 2013 by the Estate of Helen MacInnes. All rights reserved.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Did you enjoy this book?

We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at:

[email protected] or write to us at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website.

www.titanbooks.com

To Gilbert,

my dear companion,

who has gone ahead on the final journey

Table of Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

About The Author

1

The sun was edging round and soon would flood the tenth-floor living-room. By the time a July noon came to New York, thought Colin Grant, this place would be turned into a pressure-cooker. Pull down the shades, shutter yourself as if you were in Spain; yes, that was the obvious solution. Except that the light would be dimmed, and the small breeze blocked. There was no air-conditioning to solve these problems: O’Malley (who owned this place and had leased it for a year to old friend Grant) hadn’t gone to that expense; or perhaps it was his contribution to energy-saving. O’Malley was seldom here, anyway, jaunting off to Europe for his firm. Some day, Grant decided, I’ll get around to asking him what possible business is now keeping him for a year in Geneva. But, as one old Washington hand to another, information was better volunteered than requested.

He spread the photographs over the desk—one of the few relics from Washington, along with a collection of books and records, and his typewriter and files. O’Malley wouldn’t object to the coolest corner in the room being turned into a miniature office. “Just keep the place clean and aired, and scare away the burglars,” he had said. And pay maintenance, Grant thought wryly. Still, it had seemed a bargain last November, when he had seen the sun, welcome in winter, streaming into the living-room. He could work here, if not cheerfully—considering the emotional and mental agonies of these last months—then at least in privacy during the morning hours. For a moment, with his hands on the photographs of still-life paintings, his thoughts veered to Jennifer... Jennifer lying on a quiet pavement, her head smashed by a murderer’s bullet. And the killer still free, roaming Washington streets... Stop remembering, he told himself, let the wound close. Jennifer was gone.

He forced his attention back to the work before him. The article on still-lifes—seventeenth-century Dutch versus contemporary American—was due next week. He began studying the photographs again, picked up his pen. He began writing.

Once started, the sentences ran easily. His idea for dealing with the subject held his interest, kept his mind concentrating. The Dutch tables laden with fish and vegetables, the pheasants and geese hanging in a dark kitchen ready for plucking, the piles of fruit, wine-flasks and spilled goblets, a discarded lute (it was easy to see what seventeenth-century tastes were, either above or below stairs), made a rich contrast with recent American offerings—a soup tin, giant size, in lonely splendour, a huge baseball bat; or a lavatory bowl. He had just written a pungent phrase about that last little item when the doorbell rang. Three sharp little bleeps. Oh God, he thought and paused before his next sentence. Ronnie Brearely. That was the ring she used.

Leave her ringing? A repeat of three bleeps conjured her standing on the doormat outside, ready with some excuse, bearing gifts and smiles. Answer the summons? If he didn’t she’d be back again on a new pretext, or there would be ’phone calls and invitations and all the protective kindness she seemed to think a widower needed. Better face her—this time really administer the last rebuff. I’ll choose my own women, he thought, his face tight with annoyance. He dropped his pen, rose, pulled on his shirt and buttoned it almost to the collar. The bell was ringing again as he opened the door.

She was wide-eyed and breathless, the usual sweetly innocent approach that she favoured. Today the bright smile was a little uncertain. Perhaps she was beginning to get the message, he thought, hope rising: he had been trying to send it for the last three months, ever since she had decided to adopt him. Adopt him? Jerry Phillips, with whom he played hard tennis three times a week, had a harsher phrase for it. “She’s got you in her sights. Look out, man! You’re her third husband. It’s in her eyes.” Grant had laughed that off: women were feeling sorry for him, there was a lot of sisterly affection around, they weren’t all predatory, and how the hell did you rebuff kindness? “Your serve,” Jerry had said, and won that game and the next one too.

Ronnie was talking in her soft half-laughing way, her words cascading all around him. She broke off. “Are you listening? Really, Colin—”

“Sorry. I’m in the middle of writing an article.”

His cool voice and non-smiling face stopped her short. Briefly. “Well, let me put these things in the fridge,” she said, using the large brown paper bag filled with eatables to buttress her first step over the threshold. Her sudden movement caught him one step too l

ate, and she was into the small hall. She had reached the kitchen with quick short steps, even before he had finished the thought that if she had been a man, he would have said, “Get the hell out.”

“I just happened to be in the neighbourhood,” she told him brightly as he entered the kitchen. She was emptying the paper bag. “I won’t really disturb your work, go ahead with it, I’ll just get this Brie into the refrigerator and wash this Bibb lettuce for you.” She looked at the sink and the counter-top, shook her head in amused disapproval. Her shoulder-length hair, auburn veering into blonde, had been carefully curled into long thin tendrils, hundreds of them, springing out from a tight band above her forehead—the frizz effect of the with-it girl. Tanned arms were well displayed by the peasant blouse; so was one of her shoulders by the slipping neckline. Tanned legs, too, slightly straddled in the current Vogue pose that went with one hand on hip. And below the swinging skirt were twists of thong around slender ankles to anchor elaborate espadrilles that no Basque fisherman had ever dreamed of in his wildest fantasies. “I’ll tidy up around here,” she said, dropping her large canvas handbag on the table beside the food, and turned to the sink. “Needs it, doesn’t it? Where’s that cleaning woman I found for you, Colin?”

“I have a cleaning woman.”

“Once a week? Ridiculous.”

“She suits.” Particularly his budget.

“Go right ahead and finish your work.”

He began replacing the Bibb lettuce and Brie and strawberries and French bread in the paper bag. A bottle of Liebfraumilch, chilled and beaded with perspiration, was lurking inside there, too, along with a tin of pâté. A damned waste, he thought angrily, but the last husband—so the talk went—had been generous with his alimony. (The first husband had handed over a Long Island cottage and his apartment in New York City.)

She glanced round, stopped work. “But you have to eat lunch, darling. Let me fix it. At least you can give me a drink. Hock would be just right for this warm day. There’s a bottle inside the—”

“I know. And I’m not having a drink or lunch.”

“Surely,” said the soft voice, soft smile, soft sell, “surely you can’t be playing tennis this afternoon with Jerry—far too hot. You don’t have to be at the Gallery until four o’clock. Plenty of time to have a light lunch and finish your work. What is it, anyway?” She was out of the kitchen, that beachhead abandoned, heading with her brisk step into the living-room. “Oh,” she said in dismay, “this place is going to be impossible in August. Impossible. When does the Gallery close for the summer—mid-July, isn’t it?” She studied the reproductions strewn over his desk. “You work far too much.”

“Not enough.” He placed a book quickly over his manuscript.

“Sorry,” she said. “No peeking, I promise.” She moved away. “You were so comfortable in Washington. Such an enchanting house, small but perfect. Did you really have to give up all that, and your job too? Believe me, Colin, Jennifer was one of my oldest friends, and she would never, but never, have wanted you to live like this.”

She had known Jennifer at school, that was all. And she had only visited the house in Washington once. He hadn’t even been there that week-end: off on a business trip to talk the Philadelphia Museum into an exchange of paintings with Florence.

Ronnie was saying, “Don’t you miss the State Department, Colin?”

“I wasn’t State Department,” he said sharply.

“Oh well, your cultural exchange unit was under their wing. They paid for all those exhibitions. At least, they backed them, didn’t they?”

“It wasn’t my cultural exchange unit. I was a junior assistant to the Director, and I—” He stopped short, caught his rising temper. Why waste breath talking? He’d never get rid of her at this rate. “Time to leave, Veronica.” She disliked her full name. His use of it, now, and the ice in his voice, should be enough to freeze her out of here.

She didn’t appear to hear him. “A big drop in your income,” she observed, all sadness and sympathy. “That’s what worries me, Colin. August, for instance. Where are you going to spend August? All alone here, in this place?” She looked around Dwight O’Malley’s living-room and shook her head.

“There’s nothing wrong with it. Come on, Veronica, time to leave.”

“But I’ve only been here twenty minutes.” She was half annoyed, half teasing. “Can’t you spare one of your devoted admirers just a few moments?” She picked out a book, which she had been eyeing, from the shelf behind his desk. Now she was serious. “Really, Colin, I do admire you. This, for instance.” She held up the book. It had been published ten years ago when he was twenty-nine and brash enough to think his ideas would dazzle the art world. A slight little volume, now out of print, but it had helped him get the job in Washington. He took it out of her grasp and replaced it on the shelf.

She was saying, “You could write so easily in Springs. You’d love the cottage. There’s a desk in the guest-room, and it has French windows and a terrace all of its own. Why don’t you come there in August? Plenty of swimming—your choice between the Atlantic and the Sound. Tennis, too. And, of course, the kind of people you’d love to meet.” She rattled off the well-known names of three painters, a writer, and two museum directors. “There are even people around who are rich, but filthy rich. The kind who buy paintings and need advice. So good for the Gallery’s business, don’t you think?”

He could only stare at her.

“That’s part of your job there—advising people on what to buy. Isn’t it?”

He turned on his heel. “This way,” he said.

“Colin—”

He had left the room. She followed slowly. By the time she reached the hall, he was at the front door with her handbag and package in one arm.

“Colin,” she said, “if you would only try August down on Long Island—”

“No.”

“Why not? It’s so cool in the evenings, quite unlike New York. And I promise you’ll be left alone—I won’t disturb you. I promise.”

He opened the front door. “Goodbye.”

“Goodbye? Just like that.” She mustered a forgiving smile as she took the handbag. She ignored the parcel of food. “Darling, I’m sorry I arrived at the wrong time. Forgive me?”

So she hadn’t got his message. “You forgot something.” He thrust the paper bag into her arms, urging her over the threshold.

For a moment, soft sweetness vanished. The pretty mouth hardened, widened, with lips now spread in anger. “You—” She regained part control and quieted her rising voice. “You can give this to your lousy elevator boy.” She dropped the package at her feet. “There goes the hock,” she added, smiling normally once again.

He closed the door. She had got two things wrong: there was no elevator boy, lousy or otherwise; and the wine bottle, probably bolstered by a thick cushion of Brie, had given no sound of breaking. It would all have been comic, except for the ugly moment of fury. Medusa. In that brief instant, the mass of red ringlets had changed to snakes.

Depressed and angry, he made his way back to the living-room. He was already feeling a touch of guilt—it was the first time he could remember being actually rude to a woman. He had better keep Medusa in mind.

* * *

No more work on the article was possible. The phrases wouldn’t come, his train of thought disjointed. He tried cooling off in a shower, resisted the idea of going out for a late lunch—too heavy on the budget. Always that damned budget to think of. He’d have to get a full-time job: free-lance articles bolstering his part-time work at the Schofeld Gallery were barely enough to cover New York expenses. The Gallery carried prestige, of course. Its reputation was high, and his position there as adviser in acquisitions sounded impressive enough. He had been lucky to get it, even if it seemed only a temporary halt in his real career. My God, he thought as he opened a tin of sardines and poured himself some beer—it would be a heavy enough evening ahead at the Gallery with the cocktail party fo

r Dali’s illustrations of Dante’s Inferno beginning at five—do museum directors never die? At present, they all seemed to be well under retirement age, and lusty. As the junior officers in the British Navy used to toast in their wardroom, “Here’s to a bloody war or a sickly season!”

He drank his beer with the first smile he had had on his face that day: partly because of the black humour of the junior officers’ toast, partly because of the amount of useless information that was picked up over the years and then suddenly surfaced at appropriate moments. He might be drifting along in his career, but his memory was still working. Even if he might not wish for bloody wars or sickly seasons, he had one firm desire—the one that had been with him for the last ten years. He couldn’t paint—he had tried that, and admitted his failure. But he did know something about artists, past and present. And what better job than getting their works, often buried in private collections, out into the public daylight? Not by force or thievery. Getting them out through the power of friendly persuasion. With, of course, strong guarantees for their safety and protection. No private collector was ever going to unlock his sweet treasures unless he could trust their temporary guardians. That’s where the cultural boys in the State Department had been useful during his nine years in Washington: their backing had influenced several very hard heads among some of the foreign art-gatherers. But in the last three years there had been a decline in government interest as exhibition costs mounted and inflation soared. Understandable, of course. Social services and defence made art a very poor relation. What was the lecture he had been given by that determined New York Congresswoman when he had faced her on one of the minor but inevitable House committees? Man could live on bread alone if need be, but he’d surely perish on a diet of frills. Her word, frills. So much for fine art and expanded knowledge. New York, New York, you’re a helluva town, where the debts pile up and the streets go down.

Now don’t get bitter, he warned himself. The Congresswoman was worried—pushed by a hundred thousand voters clamouring for bread alone, which included a TV set, petrol at cheap prices to give them some week-end driving, and all the other inalienable pleasures that accrued automatically at birth. So don’t get bitter. Besides, there were some important exhibitions being carefully nursed around the country. The big museums could still manage that. But it took a splash of a name like Tutankhamen, or the Mona Lisa, or the Venus de Milo, to catch public support. What about the great works of art that were never on view? Unknown, because they were hidden inside a castle, a mansion, a palace, a private collection perpetually closed. Their owners, of course, saw a virtue in this, a nobility of purpose. What was the phrase he had heard so often? “Preserving art for posterity...” Whose posterity? Theirs?