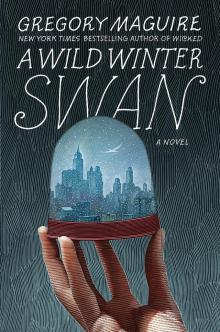

A Wild Winter Swan

Gregory Maguire

Dedication

for my brothers and sisters

John, Rachel, Michael, Matthew, Annie, and Joe

Epigraph

Clangam filii,

ploratione une alitis cigne,

qui transfretavit equora.

O quam amara lamentabatur,

Arida se dereliquisse florigera

Et petisse alta maria aiens:

Infelix sum avicula

heu mihi

quid agam misera.

Pennis solute inniti lucida

Non potero hic in stilla.

Undis quatior,

Procellis hic intense alidor exulata.

—Anonymous, Carolingian-Aquitanian origin, c. a.d. 850

Hear me, children,

sing the lamentation of the Swan

that flew out over the water.

Oh how he grieved,

for he had given up the firm land

for the high seas.

This was his bitter cry:

“I am an unlucky bird.

Alas,

how shall I endure such misery?

My wings will not support me,

the waves batter me,

the winds dash me in my exile.”

—Translation by Anne Azéma, Boston Camerata

There’s a story—the sixth brother. Give him something to do. The boy with a wing. You know the one I mean?

—P. L. Travers, author of Mary Poppins, in conversation with the author, October 1995

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by Gregory Maguire

Copyright

About the Publisher

1

Knuckles of hail rapped against Laura’s window with a musical jumpiness. Hardly tidings of comfort and joy, comfort and joy, though, when the room was an icebox. Coming downstairs to get warm, Laura trailed her hand on the greens wound round the banister. This raised a note of balsam in the air. But she knew better than to trust the false hope of the holidays.

Every green garland ends up in the ash can.

She paused, in a silence rich and pertinent to herself if to no one else, and told herself into the moment. Not a silent narration spoken in her mind, but a story as it felt, something more or less like this:

In the city of New York once stood a house on Van Pruyn Place. It was owned by a fierce old Italian importer known as Ovid Ciardi, of Ciardi’s Fine Foods and Delicacies. His stout hobbley wife lived there, too, griping the whole livelong day. Their granddaughter had come to live with them, nobody remembered why. One day she walked down the shiny fancy stairs to find two workers in the front hall. Fellows who had come out on a Saturday, no less, to repair the grouting of the stone windowsills on the top floor. But they were puttering around here instead. One was climbing a stepladder that had been set up in a circle of plaster dust and fallen fragments of ceiling. They didn’t notice the girl. She was fifteen and had long brown hair, very straight. She wished her eyes were mossy green but they were Italian brown, espresso brown. The workers didn’t notice her eyes or her. They were staring at something else.

That was as far as she could go. She didn’t know what happened next because it hadn’t happened yet. “What are you doing?”

From a hole in the plaster ceiling John Greenglass withdrew a baby—a baby something. An owl? It was still alive. “This is an item,” said John. He backed down the stepladder, cupping with both hands the clot of fussing feather. His helper, Sam, steadied him. Laura watched from the landing.

“Come lookit, such a surprise,” said Sam, gesturing.

Laura was not meant to be downstairs while the workers were there. But so much of the ordinary was overturned now. She approached as John opened his hands. Beneath the grit and plaster dust, the creature was nearly white all over. It shivered and half-flexed its wings. Maybe shocked, and also a bit of what’s-it-to-you?

“Little scamp’s scared witless,” said Sam.

“How did it get in our ceiling?” asked Laura.

John shrugged. “The coping on the roof was a mess. Mortar joints washed out. That’s where the water got in. But I don’t know how a baby owl could wriggle inside and make its way down three flights behind the walls and across this ceiling.”

“Well,” said Sam affably, “maybe a rat caught it and dragged it inside.”

“No rats,” said Laura. Rats didn’t fit into a Christmas story, even in a bitter season.

“You’re too old to be blind to rats in the city, Miz Laura.” Sam made cooing sounds at the small owl, who didn’t reply. “What’re you, fourteen?”

“Fifteen.”

John shook his head. “Fifteen, Miss Laura, too grown-up to shiver at real life.” Mocking her grandfather’s accent, John pronounced Laura’s name broadly, in three syllables: Laow—OO—rah. Like the bulb horn of an old-timey Model T.

“It’s scared to death. Let it go,” she said.

John shrugged. “You’re the boss.”

Sam was more tender than John. “Give it here, John. I can take it in my lunch box and bring it to the park when it’s ready. Some other birds will raise it up.”

“A dog will eat her, or a cat,” Laura protested.

The door under the back stairs, which led to the kitchen below, swung open. Out lurched Mary Bernice, alerted by the fuss. “You’s not to be loitering in the hall with no contractors,” said the cook. “Laura Ciardi, you get upstairs as you’re told to do. No consorting. Not on my watch.”

“You’re not in charge of me,” said Laura. Hardly a withering retort, but she was better with sentences in her head than in her mouth.

“I’m keeping you safe from your elders lest they get word of such shenanigans.” Like some kind of stage nanny, the cook flapped her apron at Laura.

“She doing nobody harm, Laura a good girl,” said Sam. “Lookee, my baby owl. It gots eyes like little black punch holes.”

“For sure, if a bird comes in the house, a death comes next,” replied Mary Bernice. “Get it out for once and for all. Laura, your grandda will be home any moment. Trouble twice over and never mind apologies. Will you get back upstairs while there’s young fellows working on the premises. Go now as I’m telling you, go.”

The white bird twisted its head on its neck and glared across the room to where Laura stood on the stairs.

The little owl baby looked at the orphan girl as if wanting to give her a message. But then the handsome workman closed his hand again and dropped the owl into his companion’s lunch box. The lid fell shut softly, and softly did the clasps clasp. The little owl in darkness. Like a tomb.

“She’ll suffocate in there,” said Laura.

“It’s a she? Okay then. I’ll see she gets some air and something to eat,” said Sam. Laura didn’t know his last name. He was on his way to being dark-skinned and had a soft, sing-along voice. “If she can fly, why, I’ll let her fly away.”

“How did you even know there was a baby owl in the ceiling?” asked Laura.

John said, “We were tracking the leak from the l

edge outside your window, up top of the house. It runs down the wall of the master bedroom below you. Stained your grandparents’ room, then skipped the parlor below that. Must’ve followed an internal channel, and so it emerges here. Water does that.” Hence, Laura supposed, the torn and crumbled plaster and the glimpse of lathes. “Reached in to see how much rot we’d have to pull down, and what do we find but this little bundle. Surprises in New York City every day of the year, I always say.”

“Your grandfather, he won’t be happy to see this surprise, the week before Christmas,” said Sam.

“O come all ye faithful,” sang John, “joyful and triumphant.” Then, speaking, “I always wondered why not, O come all ye doubtful, lazybones and losers.”

“They’re invited too,” said Mary Bernice, “but they have to stand in back because there’s an unruly number of them. Hoo, listen up and buckle your britches, lads, the mister’s on the stoop. Laura, shoo!”

Laura flew up the stairs, reaching the second floor just as the key turned in the front door and her grandfather came in, stomping snow off his overshoes. At the sight of the mess in the front hall, a sound of under-his-breath cursing in Italian.

Across the landing Laura tiptoed. She bypassed the office and the parlor doors, and pivoted to the back staircase, which went down to the kitchen and upstairs too. She rose to the floor above, skirting the door to her grandparents’ room, and up once more, till she reached the top of the house.

The governess’s room, unused since Laura was twelve, was full of junk removed from the box room. Opposite the top of the stairs, across the landing, Laura’s little bathroom was squeezed in alongside the bricks of the chimney stack. In the front of the house, two pinched rooms. The box room stood haunted and echoey on the right-hand side, empty but for some tools and buckets and work gloves on the floor. On the left, Laura’s bedroom. Its single window, set in a slanting ceiling inside the mansard roof of the top flight, was filled with white wings.

She saw wings.

No, not wings. Shadows of snowflakes, big fat snowflakes falling outside in the icy December dusk.

2

Laura threw herself on her bed. She lay in velvet shadow. She took in how things looked in the slop of her own life. The hall light, slanting through her doorway, picked out the grey-sheeted linoleum tacked in place with brass strips, the faded flowery wallpaper. Here and there the archaic lilacs were browned with waterstains from other winter leaks.

She could hear the rhythm of Nonno’s interview with John and Sam. Subdued and civil tones, until the front door opened again and Nonna came in. Laura’s grandmother had never sung on the stage and her voice could hardly be called musical, but she clinched her entrance every time like a pro.

Whose story is it now? Whoever talks the loudest when they walk through the door, do they own it?

Right on schedule, the orchestrated hysterics of Laura’s grandmother. That baby owl, trapped in a lunch box, probably scared to death from the drama. Behind the door to the kitchen steps Mary Bernice was listening, too, Laura would bet on it.

Isabella Bentivengo Ciardi would be clutching the two ends of the fox fur around her neck as she harangued the men who had perpetrated this inconvenience, it amounted to a catastrophe, a disaster, Madonna mia! That last was not a curse, but a prayer. Mother of God, what you ask of me now, eh? prayed Nonna Ciardi. A dinner was to happen here this week, did none of them understand this?

Laura got every syllable. Nonna Ciardi didn’t need mechanical assistance when she was ready to broadcast the state of her nervous disposition. Nonno said his wife could be heard nightly from Hell’s Kitchen to Astoria, and on clear nights as far as Randalls Island.

“But Vito, Vito, we have family coming on Christmas Eve, my elevated sister, her superior husband. And our house looking now like what, like what, I ask you? Like a goat shed on a back road in Calabria! What it says to them? I ask you, Vito!” The more upset she got, the closer she came to losing the Rules of Better Speech that she picked up at the Ladies’ Auxiliary seminars at church on Tuesdays.

Nonno’s voice was quiet but firm. He preferred to be called Ovid, or Signore Ciardi. Vito was too old country, Vito was too Esquilino, too down-and-out-in-Mussolini’s-Rome. Ovid was Vito turned backward, sort of, and the first vowel softened. To his wife he now became prophetic. The ceiling would be repaired. The guests would be delighted by this lovely house in Van Pruyn Place. They need not know how it had come into Vito’s possession. They need not hear that the ceiling had just collapsed. It would look rich as Rockefeller’s.

“Jenny and her man will smell the raw paint, Vito, they will smell desperation!”

“And if loose stone from top of house fall on their heads as they stand at front door, Bella? That would be better to happen? Buon Natale, riposa in pace?”

Laura could not hear any more of what Nonno Ciardi was saying to calm down his wife, but her voice dropped, pianissimo, until what carried up three flights of steps was only the urgency of her syllables.

Laura watched the snow make feathers upon her wall. The snow had a glow of its own. The afternoon darkened. Downstairs, doors opened and closed emphatically.

The girl thought: Doors have a language, too. They talk to each other.

The workers were returning materials to John Greenglass’s rusty old blue truck, probably. Even if Laura had stood and craned, she wouldn’t have been able to see it at the curb. The street too narrow, the house too high.

From below, Mary Bernice hissing. Her voice like the rasp of a match on sandpaper. (She smoked every night after washing up the dinner dishes.) “You’re wanted in the parlor, Laura. Your granny needs to speak to you.”

Laura waited on her bedspread until Mary Bernice called again, just to hear the increased impatience in the cook’s voice. Then Laura darted down two flights, slowing to a more ladylike pace as she approached the parlor. The cook was lurking with a beady expression. “Bring in this tea for me, will you? And Laura—I’m going to church tonight. You want to come with me?”

“You think I’m in need of grace, too?” said Laura’s words, but her tone said Nope.

“Laura,” cooed Nonna without looking up. She was flipping through the mail. Her ankles were crossed upon the new wall-to-wall, which still smelled of glue and resin. Laura examined her grandmother.

The old woman was worn out. Her hands trembled as she tore open the bill from the Consolidated Edison Company. Her lips pursed in worry. Who knew what troubles rested upon those stooped shoulders?

“Don’t stand there gaping like a chimpanzee. Close the door. There’s a draft with all that coming and going. My tea, please, and then sit down. I haven’t got all night,” said Nonna.

Actually the old grandmother was something of a bitch.

No, that was too intense, but Laura couldn’t rethink it now. She crossed the room, leaving footprints in the plush pile of the rug that Mary Bernice would eradicate tomorrow with the carpet sweeper.

“So much to try to manage at this time of year,” said Nonna. Laura waited. Nonna’s rhetorical practice was to review her schedule of troubles aloud before alighting on the one appropriate to her audience. “My sister Geneva and her mighty husband, Mr. Corm Kennedy, are coming for Christmas Eve. She’s your great-aunt. I’ve told you this.” Nonna had recovered her artificial upper-class diction, sort of.

“You sure have. Is Mr. Corm Kennedy related to our president?” asked Laura.

“I doubt President John Fitzgerald Kennedy would even know. He has had other things on his mind, what with all this Cuba annoyance. His is a large Irish family with a thousand cousins. But you must not ask Mr. Corm Kennedy about his relations. I’m told that’s rude.”

“Mary Bernice could ask him. She’s from Ireland.”

“Don’t interrupt, Laura. And don’t be nosy. Listen to me. Since Mr. Corm Kennedy is a new member of our family and my glamorous sister is trying to show him off, I want us to appear the equal to him. Good with the manners, perfec

t with the food. Sure in our feeting. Footing. Unashamed, Laura, because we have nothing to be ashamed about. Do you understand?”

“You’ve mentioned this before, Nonna. Every night for two weeks.”

Nonna sighed. “Hand me my wrap from the pouffe, please Laura, I can’t shake the chill. A wet snow, and wind? You wouldn’t believe. I could hardly see the curbstones on Lexington Avenue.”

Laura did as she was told.

“But to the moment at hand. My dear, I have some unsettling news for you.”

“Is it about Mama?”

Isabella Bentivengo Ciardi straightened her spine and fixed Laura with a steel pin of an expression. “I’ve told you if there is ever any news I will not keep it from you. There is no news.”

That was all that mattered; nothing else mattered. Then Nonna said, “We have found you a finishing school.”

“I don’t want to go back to school. I hate school.”

“You are too young to make up your own mind about that. In any case, it’s against the law for us to keep you home merely because your friends despise you.”

“They don’t bother to despise me, I’m not worth the effort. And they aren’t my friends. They just think I’m an idiot. They laugh at me. I’m not going back there.”

“Your grandfather and I are not so blind even if we wear the bifocals. We see. We have been talking to Monsignor and to Mother Saint Boniface. They have found an ideal spot for you. If you finish three semesters there, this school will agree to give you the certificate. Diploma, I think it’s called. A small win, Laura, but it is a win.”

“Will I have to take the subway? I don’t like it downtown.”

“It is not within the reach of the subway,” said Nonna, cautiously. In the best of times Laura’s grandmother had an uncertain grasp of the subway map. The hesitation, however, didn’t sound good. “It’s in Montreal,” continued Nonna. “We’ll go there by train.”

Laura knew she was sometimes slow to pick up what was going on. But: “Mon-tre-al? Not the one in Canada?”