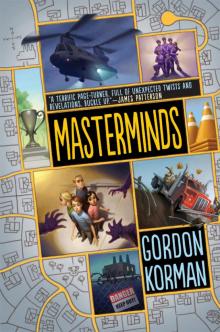

Masterminds

Gordon Korman

DEDICATION

For Jay Korman, Sports Mastermind

CONTENTS

Dedication

1. Eli Frieden

2. Amber Laska

3. Malik Bruder

4. Eli Frieden

5. Hector Amani

6. Tori Pritel

7. Eli Frieden

8. Malik Bruder

9. Eli Frieden

10. Tori Pritel

11. Eli Frieden

12. Tori Pritel

13. Malik Bruder

14. Hector Amani

15. Amber Laska

16. Eli Frieden

17. Hector Amani

18. Eli Frieden

19. Tori Pritel

20. Amber Laska

21. Malik Bruder

22. Eli Frieden

23. Amber Laska

24. Eli Frieden

25. Tori Pritel

26. Malik Bruder

27. Eli Frieden

About the Author

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

1

ELI FRIEDEN

It’s a one-in-a-million shot, and we nail it.

Just not in the way we planned.

I lie against the cool stone of the pool deck and peer into the filter opening. I can make out the tip of the boomerang, but I can’t quite jam my hand in deep enough to get a grip on it. “It’s stuck.”

“What are the odds?” Randy groans. “You could throw that thing fifty thousand times and never get anywhere near the filter. But one little challenge, and bull’s-eye.”

Randy’s famous around Serenity for his “challenges,” which usually involve catching something uncatchable while riding a bicycle, jumping on a pogo stick, swinging on a rope, or rolling inside a truck tire. As his best friend, I’m usually the guinea pig for Randy’s cockamamie ideas. Like today’s challenge: Randy throws the boomerang out the window of the tree house and I’m supposed to leap off the diving board, snatch it out of midair, and do a cannonball into the pool. Only I miss, the cannonball turns into more of a belly flop, and the boomerang disappears inside the filter.

“Maybe Mr. Amani can get it out,” I suggest. He’s the local handyman, whose job includes pool maintenance and just about everything else from plumbing and electrical work to ridding your crawl space of scorpions and baby armadillos.

“And maybe he can’t, which means my folks will have to call the pool guys.”

That’s a much bigger deal than it sounds like. There’s no pool company in Serenity, and the nearest town is eighty miles away. It can take weeks to get anybody to schedule a trip out here, and in the meantime your pool turns to soup. Mr. and Mrs. Hardaway aren’t going to be thrilled with this—although they’re pretty used to it, having dealt with Randy for thirteen years.

It’s definitely a drawback to living in a small town in the middle of nowhere. Every time something like this comes up, though, my dad just points to the newspaper clipping on our fridge:

SERENITY VOTED #1 IN USA FOR

STANDARD OF LIVING

He leads me through the bullet points in the article: no crime, no unemployment, no poverty, and no homelessness. The amazing part isn’t so much that we have none of those things, but that other towns do, and they’re okay with it. It must be awful. Of course, there are only 185 people in Serenity, so it’s not so hard to make sure all of them have someplace to live and work. We’ve got the Serenity Plastics Works, one of the largest producers of orange traffic cones in the United States. Our school has the highest test scores in New Mexico. We’re right on the edge of Carson National Forest, surrounded by canyons, foothills, and woods, and the sun shines practically every day. True, it gets pretty hot sometimes, but we don’t bake like they do in those real desert towns. No wonder Dad’s so proud. He’s the mayor, which sounds like a big deal, but it really isn’t. His salary as mayor is one dollar per year, and he always claims he’s overpaid.

Our parents constantly remind us how lucky we are, and we always roll our eyes. But you know what? They’re right. We are lucky—just not when the pool filter is busted, and the nearest repair is in Taos.

Randy makes an executive decision. “I’m not going to tell my folks about it. I’ll just act ten times as amazed as everybody else when they find the boomerang in there.”

I’m a little uncomfortable. That feels like lying. I know people do it all the time on TV and in books. But here, we’re honest no matter what. Even when it’s hard to be, or when it could get you in trouble. That might sound a little too good to be true, but I think that’s why people here are so happy.

“We could go to my pool,” I suggest, anxious to change the subject. “No boomerang, though.” My dad is twenty times as strict as the Hardaways. He’s the school principal as well as the mayor. That is a big a job. There’s only one school in town.

“Nah, I’m sick of swimming.”

“We could hang out in the tree house.”

“Boring,” he declares. “Every kid in town has a tree house and none of them are any fun. And don’t say video games either. It doesn’t matter how good your home theater is when all your games are lame.”

“Our games aren’t so lame,” I remind him. Randy and I have figured out a way to tweak the game software to unlock hidden features, like crashing cars and fighting with real weapons. Turns out I’ve got a knack for that kind of thing. I can do it with my iPad and computers too. It’s strictly hush-hush, because everybody in Serenity is antiviolence. I am, too, but in a video game, I figure where’s the harm in it? It’s not like it’s actually happening.

“Yawn.” Randy gets this way sometimes, where nothing satisfies him. Basically, he’s a crab. Believe it or not, it’s one of the main reasons I like him. You don’t hear much complaining in Serenity. Randy always manages to find something, though. It’s almost as if he’s daring the universe to do a better job, no matter how great things already are. I think my dad would be happier if I found a different best friend. But let’s face it, in a town with only thirty kids, there’s not much to choose from. And anyway, you don’t find best friends. Best friends just happen.

“So what are we going to do?” I ask him.

“Let’s get out of here. Let’s go somewhere.”

I brighten. “They’ve built that new high slide at the park.”

He’s unimpressed. “Big deal. You climb up so you can come down. Let’s do something cool.”

“Like what?”

“Like—” His eyes dance. “Check out the most awesome old sports car you’ve ever seen.”

“Sports car?” I echo. When you live in a place this small, not only do you know every car; you could probably recite the license plate numbers by heart. When somebody gets a new vehicle, three-quarters of the town show up to see it. There are plenty of fancy SUVs and sedans, but no sports cars.

“It was the weirdest thing. My dad and I were hiking a few miles out of town and we found an old, abandoned ranch—busted-up fences and a house that was nothing but a pile of toothpicks. The only thing standing was this rusted Quonset hut. And when we went inside, the car was there. The tires were flat, and the whole thing was buried in dust and spiderwebs, but it was beautiful. My dad said it was Italian—an Alfa Romeo. It had Colorado license plates from 1961.”

“Wow,” I say.

“Yeah,” he enthuses. “Let’s go see it.”

“What—right now?”

Randy shrugs. “What are you waiting for—Christmas? It’s not too far. Grab your bike and let’s go.”

I hesitate. “I have to ask my dad.”

He looks pained. “Bad idea. I know your old man.”

Poor Dad. Felix Frieden is kind of a joke among the kids in town, with his thre

e-piece suits, and his shined shoes, and his no-nonsense attitude. They just see his principal side.

Randy has a point, though. “You think he’ll say no?”

“Why give him the chance?” Randy insists. “The car’s only a few miles away. We’ll be there and back before he even knows you’re gone. Come on, Eli, live a little.”

“It’s just—” I’m embarrassed to say it, but I have to be honest. “I’ve never been out of town.”

“Neither have I—not since we visited my grandma when I was six—”

“No,” I interrupt. “I’ve never been anywhere out of town. Not even where your dad took you hiking.”

“What about that time in science when our class went fossil hunting?” he challenges.

“That was still inside the town limits. Mrs. Laska said so.”

He’s amazed. “But haven’t you ever passed that stupid sign—the one that says: Now Leaving Serenity—America’s Ideal Community?”

I shake my head. “I’ve never even seen it.”

“Well, you’re going to see it today,” he decides. “Grab your bike.”

That’s another thing about Randy. He won’t take no for an answer. He doesn’t exactly bring out the best in me, but we have a great time together, and that counts for a lot. He does the things I daydream about but don’t have the guts to try.

Until today.

Only one road passes through Serenity, a two-lane paved ribbon everybody calls Old County Six. We pedal west along it, riding right down the center over the faded, broken line. There’s little fear of meeting traffic in either direction. All decent highways cross New Mexico well to the south. If you hit Serenity, chances are you’re lost.

As we bike on, I spot the gully that was the site of the fossil-hunting trip. I am now farther from home than I’ve ever been in my life. Can it really be this easy? You just jump on a bicycle and ride out of town? It seems like cheating somehow, breaking some overarching Law of the Way Things Are Supposed to Be. Yet here I am, just doing it. It’s kind of exhilarating—at least, I’ve never been so aware of the beating of my heart and the blood pumping through my veins.

I feel a little strange about not telling Dad. Not that I need his permission—I’m thirteen years old. Besides, he never specifically said not to ride my bike out past the town limits. I’m not breaking any rules, but I know he’ll be disappointed if he finds out about this. Face it: If I don’t need to ask permission for this ride, how come I snuck my bike out of the garage? I try to push the thought from my head as I pedal away.

I glance over my shoulder at Serenity—the perfect rows of immaculate white homes, the swimming pools positioned on the lots like aquamarine postage stamps, the basketball hoops lined up like sentries, all lovingly set down amid the striking southwestern landscape. In this view I find my answer to the nagging question of how a person could spend thirteen years here without ever once setting foot outside the town proper. Why would I need to? When it comes to fun or comfort, we’ve got it all. We’ve got the stuff adults want too—a great school and great jobs. We’ve got the three Essential Qualities of Serenity citizens—honesty, harmony, and contentment. We’ve heard about the bigger towns and—even worse—cities. They stink of garbage and everything’s crumbling, and crime is so bad that nobody can trust anybody else. People spend their time in fear, hunkered down behind locked doors and alarm systems.

At the same time, it’s almost startling how tiny the town is, even from this distance of barely a mile. If it wasn’t for the factory, you wouldn’t notice it unless you knew what to look for. I guess that’s the Serenity Miracle our parents are always talking about—that so much quality of life can be held in such a small package.

“How much farther?” I call ahead to Randy.

“Probably another twenty minutes.”

After a bend in the road, a tall butte obscures the town altogether. It completes the feeling of being out there.

Randy doesn’t seem to notice at all. “Look!” he shouts back at me, waving his arm to the right.

It’s the sign Randy mentioned—the one about leaving town. In contrast to spotless and impeccable Serenity, it’s surprisingly faded and weather-beaten. I squint at the bottom, where the warning No Gas Next 78 Miles has been tacked on.

I’ve done it. I’ve left town. I survey the rocky hills and scrub pines and brush. I don’t know what to call this, but it’s not Serenity anymore. After more than thirteen years, I’m officially Somewhere Else. And how does it make me feel?

To be honest, kind of scared. I’ve never done this before, never lost visual contact with my hometown. By the time I get to see this Alfa Romeo, I’ll be so stressed out that I won’t even be able to appreciate it. I’m overthinking this whole business to the point where it’s making me sick to my stomach.

Well, I’m not turning back. I made it this far, and Randy will never let me hear the end of it if I don’t follow through.

But I really am sick—and getting sicker. The nausea grows stronger, rising up the back of my throat. There’s no way it’s just from being nervous. This is something physical. What did I have for lunch today? I can’t remember, but whatever it was, it’s coming up, and soon. My stomach twists in a paralyzing cramp, and my head hurts too.

“What’s with you, Eli?” Randy calls back in annoyance. “Running out of gas already?” His expression changes when he sees me. “Hey, are you okay?”

I’ve slowed down, although I hardly notice it. Only pure stubbornness keeps my legs pumping. I’m in agony, blinded by the kind of headache that lodges behind the eyes like a glowing coal, pulsating and doubling in intensity. The pain is unimaginable. It’s not just a terrible thing; it’s the only thing.

I’m not even aware of toppling off the bike until my chin strikes the road. Fire erupts on my forearms where they scrape the rough pavement. I see Randy kneeling over me, feel him shaking me, but I’m powerless to respond. I can only focus on one thought:

I’m dying.

What happens next is so shocking, so bizarre, that I’m sure I’m imagining it, delirious with pain. A loud, rhythmic roar swells around Randy and me, and strong winds whip down on us. A dark shadow moves directly overhead, growing larger and larger as it descends. An enormous military-style helicopter settles on the road, its rotor buffeting us with air.

The hatch opens, and out jump six men in identical indigo uniforms and wine-colored berets.

“Purple People Eaters!” Randy breathes.

Through a fog, I can barely make out the distinctive tunics of the Surety, the security force of the Serenity Plastics Works that doubles as the town police. It takes all the strength I have left to spread my arms to the rescuers.

“Help me,” I whisper, wondering if they can even hear me over the thunder of the chopper.

“Eli . . .”

I can’t seem to pinpoint the source of the voice. Through blurry vision, I can just make out the outline of a face peering down from above.

“Eli, wake up.”

“Dad?” I’ve never been so relieved to see him. My father’s familiar features come into focus—thin lips and pale eyes, the color of a frozen lake. It’s his Principal Stare, although it’s hard to imagine him looking any different if he was an astronaut or a fruit picker or a rock star. Most kids go a long way to avoid that expression, but to me, it’s familiar and even comforting, my earliest memory.

I’m in one of the two beds in Serenity’s tiny doctor’s office and health clinic. An IV tube tugs at my arm. And that means . . .

It’s all true. It comes back like a delayed-reaction recollection of a terrible nightmare. The bikes. The collapse. The Purple People Eaters . . .

“I never thought I’d see you again, Dad.” The lump in my throat swells to cantaloupe size. “I never thought I’d see anybody!”

The Stare softens and he leans over and hugs me. “You gave us quite a scare.”

“What happened?” I feel better, but by no means back to normal. An imp

enetrable grogginess covers me like a curtain. The nausea and headache are gone, but the memory of so much pain and fear haunt me. The idea that it’s possible to feel so awful, and that maybe I’ll feel that way again one day—it’s changed me.

On the other hand, I’m alive, which is kind of a surprise. “What happened?” I repeat.

Dad breaks the hug. He tries, but he’s just not a touchy-feely guy. “Dr. Bruder isn’t quite sure. Dehydration, maybe.”

“I was fine until suddenly I wasn’t anymore. I was on my knees throwing up nothing and holding on to my head to keep it from falling off.” My voice cracks a little. “I honestly believed I was going to die.”

“But we can’t rule out the possibility of an extreme allergic reaction to something growing out there,” Dad goes on briskly.

I stare at him, wanting to be babied just a few minutes longer. Briefly I wonder if my mom would have been the warm and fuzzy parent. She died when I was little, so I’ll never know. I don’t even remember the smiling face in her portrait on our mantel. It’s my job to replace the flowers every week. The picture is familiar, but the person in it is a stranger.

Don’t get me wrong. My father has always been there for me. I spit up on his tailored suits as a baby. When I toddled my first steps, his sure hands steadied me. I even remember him in the pool supporting my stomach when I was learning to swim—no small thing for a guy who rarely loosens his tie. But a teddy bear he’s not.

“Is Randy all right? Did the Purple People Eaters pick him up too?”

The pale eyes frost over in disapproval. “We don’t use that term.”

I bite my tongue. Maybe you don’t, but that’s what every kid in town calls them. What do you expect when you dress them up like a platoon in plum?

“You’re very lucky the Surety stumbled on you when they did,” he continues.

“Stumbled?” It isn’t exactly how I’d describe it. “Is that what you’d call a giant helicopter filled with purple storm troopers descending from the sky in a blizzard of flying dust?”

When my father frowns, his lips retreat into a pencil-thin line above his chin. “Storm troopers—where would you pick up a word like that?”