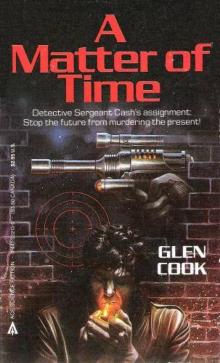

A Matter of Time

Glen Cook

A Matter of Time

by Glen Cook

Detective Sergeant Cash's assignment: Stop the future from murdering the present...

May 1975. St. Louis. In a snow-swept street, a cop finds the body of a man who died fifty years ago... It's still warm.

July 1866, Lidice, Bohemia: A teenage girl calmly watches her parents die as another being takes control of her body.

August 2058, Prague: Three political rebels flee in to the past, taking with them a terrible secret.

As past, present, and future collide, one man holds the key to the puzzle. And if he doesn't fit it together, the world he knows will fall to pieces. It's just A Matter of Time!

A MATTER OF TIME

An Ace Science Fiction Book/published by arrangement with the author

PRINTING HISTORY

Ace Original/April 1985

All rights reserved.

Copyright © 1985 by Glen Cook

Cover art by Barry Jackson

This ePub edition v1.0 by Dead^Man Jan, 2011

This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by mimeograph or any other means, without permission.

For information address: The Berkley Publishing Group,

200 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016.

ISBN: 0-441-52213-0

Ace Science Fiction Books are published by

The Berkley Publishing Group, 200 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016.

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

I

On the Z Axis;

12 September 1977;

At the Intersection

Total darkness. Silence broken only by restless audience movements.

Suddenly, all-surrounding sound. A crossbreed, falsetto yodel/scream backed by one reverberating chord on the bass guitar. A meter-wide pillar of red light waxes and wanes with the sound.

Erik Danzer is on.

Nude to the waist, in hip-deep vapor, he rakes his cheeks with his fingernails. He is supposed to look like an agonized demon rising from some smoldering lava pit of hell.

Light and sound depart for five seconds.

Owlhoot sound from the synthesizer.

Sudden light reveals Danzer glaring audience right. Light and sound fade. Repeat, Danzer glaring left.

Harsh electric guitar chords, with the bass overriding, throbbing up chills for the spine. Mirror tricks, flashing, put Danzer all over the stage, screaming, “You! You! You!” while pointing into the audience. “You girl!”

The lights stay on now, though dimly, throbbing with the bass chords. Danzer seems to be several places at once. The pillar-spot moves from man to man in the band.

The man in the shadowed balcony, whose forged German Federal Republic passport contains the joke-name Spuk, neither understands nor enjoys. His last encounter with British rock was “Penny Lane.” He does not know that Harrison, Lennon, McCartney, and Starr have gone their separate ways. He has never heard of “Crackerbox Palace,” Yoko, Wings, “No, No, No, No”...

He wouldn’t care if he had.

The pillar roams. The spook lifts the silenced Weatherby. Through the sniperscope, after all these years, the target’s face is that of a stranger.

The bass guitarist’s brains splatter the organist.

Spuk is a half mile away before anyone can begin sorting the screaming mob in the hall.

II

A Pause for Reflection

Sometimes the balloon is booby-trapped.

Grinning little vandal, full of pranks, you jab with your pin. Ouch! It isn’t a balloon at all. It’s a Klein bottle. The pin conies through behind you, butt high.

If you’re obstinate, you play Torquemada with yourself for a long time.

Take a strip of paper. Make it, say, two inches (or five centimeters if you’re metrically minded) wide and fifteen (40 cm is close enough) long. Give it a half twist, then join the ends. Take a pencil and begin anywhere, drawing a line parallel to the paper’s edge. In time, without lifting your pencil, you will return to your starting point, having drawn a line on both sides of the paper.

The little trickster is called a Moebius Strip. You might use it to win a beer bet sometime.

Now imagine joining the edges of the strip to form a container. What you would create, if this were physically possible, is a hollow object whose inside and outside is all one contiguous surface.

It’s called a Klein Bottle, and just might be the true shape of the universe.

Again, you could begin a line at any point and end up where you started, having been both inside and out.

There is always a line, or potential line, before your starting point and after, yet not infinite. Indeed, very limited. And limiting. On the sharply curved surface of the bottle the line can be made out only for a short distance in either direction. You have to follow it all the way around to find out where it goes before it gets back.

III

On the Y Axis; 1975;

The Foundling

Norman Cash, line-walker, began to sense the line’s existence at the point labeled March 4,1975.

It was a Tuesday morning. The sneak late snowstorm had dropped fourteen inches.

“It’s killing the whole damned city,” Cash told his partner.

Detective John Harald packed a snowball, pitched it into the churn of Castleman Avenue. “Shit. I’ve lost my curve-ball.”

“We’re not going anywhere with this one, John.”

At 10:37 P.M. on March 3, uniformed officers on routine patrol had discovered a corpse in the alley between the 4200 blocks of Castleman and Shaw.

Ten-thirty, next morning, four detectives were freezing their tails off trying to find out what had happened.

“Hunch?” The younger man whipped another snowball up the street. “Think I got a little movement that time. You see it?”

“After twenty-three years, yeah, you develop an intuition.”

As a starting point the corpse had been little help. White male, early to middle twenties. No outstanding physical characteristics. He had been remarkable only in dress, and lack thereof: no shirt, no underwear, no socks. His pants had been baggy tweeds out-of-style even at Goodwill. He had worn a curiously archaic hairstyle, with every strand oiled in place. He had carried no identification. His pockets had contained only $1.37 in change. Lieutenant Railsback, a small-time coin collector, had made cooing sounds over the coins: Indian Head pennies, V nickels, a fifty-cent piece of the kind collectors called a Barber Half, and one shiny mint 1921 Mercury Head dime. Sergeant Cash had not seen their like for years.

He and Harald were interviewing the tenants in the flats backing on the alley. And not making anyone happy.

They were pressed, not only by the weather but by fifty-two bodies already down for the year. The department was taking heat. The papers were printing regular Detroit comparisons, as though there were a race on. The arrest ratio pleased no one but the shooters.

“That’s the way it is,” Cash mumbled. He shivered as a gust shoved karate fingers through his coat.

“What?” Harald kneaded the elbow of his throwing arm.

“Nobody wants to help. But everybody wants the cops to do something.”

“Yeah. I been thinking about taking up jogging. Getting out of shape. What do you think?”

“Annie grew up on this block. Says it’s always been tough and anti-cop.”

“She married one.”

“Sometimes I think maybe one of us wasn’t in their right mind.”

The flats had been erected in the century’s teen years, to house working-class families. The two-and four-family structures had not yet deteriorated, but the neighborhood was beginning to change. For two decades the young people had been fleeing to more modern housing

outside the city. Now the core families had begun to retreat before an influx from the inner city. Soon the left-behinds would be people too poor to run. And landlords would give up trying to stave off the decay of properties whose values, they felt, were collapsing.

“I thought we’d get some cooperation ‘cause they know us,” said Harald, after having been cold-shouldered by a high-school classmate. Cash lived just two blocks away, on Flora; John had grown up in the neighborhood.

“Badge does something to people. Puts them on the defensive no matter how hard you try. Everybody’s got something to feel guilty about.”

The entire morning had been a no go. People had answered their questions only reluctantly, and had had nothing to tell. No one had seen or heard a thing.

Not that they cared, Cash thought. They just answered fast and true to get the cops off their doorsteps.

Cash had met a girl once, Australian he now suspected, who had had a strange accent. That had been a long time ago, college days, before he had married. He no longer remembered who had introduced them, nor what the girl had looked like, just her accent and the fact that he had mimicked it, thinking she had been putting him on. He still felt ashamed of the incident.

Little things like that hang with you, he thought, and the big things get forgotten.

The memory was triggered by the old woman at 4255, Miss Fiala Groloch.

Miss Groloch’s was the only single-family dwelling on the block, a red-brick Victorian that antedated everything else by at least a generation. He found it odd and attractive. He had been having a love affair with stuffy, ornate old houses since childhood.

Miss Groloch proved more interesting still. Like her house, she was different.

He and Harald grumped up her unshoveled walk, onto a porch in need of paint, and looked for a bell.

“Don’t see one,” said John.

Cash opened the storm door and knocked. Then he saw the bell, set in the door itself. It was one of those mechanical antiques meant to be twisted. It still worked.

Miss FIALA GROLOCH was the name printed in tiny, draftsman-perfect letters on a card in a slot on the face of a mailbox that looked as if it had never been used. Miss Groloch proved to be old, and behind her the interior of her house looked like a hole-up for a covey of old maids.

“May I help you?” Her accent was slight, but the rhythm of her syllables conjured visions of tiny European kingdoms perishing beneath the hooves of the Great War.

“Police officers, ma’am,” Cash replied, tipping his hat. That seemed compellingly appropriate. “I’m Detective Sergeant Cash. This’s Detective Harald.”

“Well. Come in. Is very nasty, yes?”

“Sure is. Who’d have thought it this late?” To John, whispering, “Knock the shit off your shoes, Hoosier.”

They followed the woman to her parlor, exchanging frowns. That curious accent. And she talked slowly, as if trying to remember the words.

“It has been a long time since company I’ve had,” she said apologetically, clearing a piece of needlepoint from a chair that, Cash suspected, had been an antique before his birth. She brisked to another, woke a fat tomcat and shooed him. “Tea I will have in a minute.”

“No thank you, ma’am,” said Harald. “We’ve only got a minute. Sorry to bother you like this, but we’ve got to visit everybody on the block.”

Cash chuckled. John was trying to be genteel. It was the contrasts. Harald’s contemporaries had all the gentility of Huns in rut. But that house, and that woman, demanded it.

“Oh, fooey. What bother? Already the pot is hot. Just time to steep it needs. You Jungen are always in so big a hurry. Sit. Just sit. Be comfortable.”

What could they do? The little lady rolled along like a train. They hadn’t the heart to derail her.

She was tiny, under five feet tall, all smile and bounce. She reminded Cash of his wife’s great-aunt Gertrude, who had come from England to visit the summer before. Auntie Gertie had been a hundred-fifty pounds of energy jammed into an eighty-pound package. Except in terms of spirit she was indescribable.

They exchanged shrugs and glances in her absence, but neither voiced his fear that they had been shanghaied by a lonely old woman who would use them as listening butts for slice-by-slice accounts of her seventy operations.

Cash studied his surroundings. Everything had to be older than Miss Groloch herself. It could have been a set for an 1880s drawing room, crowded as it was with garish period impedimenta. Most moderns would have found it distressingly nonfunctional and cluttered. Cash felt comfortable. Something in him barkened back to good old days he had never lived himself. But, then, as his sons had often told him, he was an anachronism himself. He was an idealistic cop.

There was no television, nor a radio, or a telephone. Incredible! The lights were the only visible electrical devices. Gas jets still protruded from the walls. Would they work? (He was unaware of the difference between natural and lighting gas.) An old hot water heating radiator stood in a corner, painted silver. Had her furnace been converted from coal? There were still coal burners around, but he couldn’t picture Miss Groloch running downstairs to shovel.

She returned with delicate, tiny china cups on a silver tray.

And cookies, little shapes with beads of colored sugar like his wife had made for Christmases before the boys had grown too old for productions. There was sugar in lumps for the tea, with tongs, and cream. And napkins, of course. Luckily, she came to Cash first. John was too young to know the rituals. Cash had had maiden aunts with roots out of time, leapfrogging a generation into the past. Harald did a credible job of faking it, though, and left the talking to Norm. He nibbled cookies and waited.

“Now, then,” said Miss Groloch, seating herself primly at the apex of a triangle of chairs, “slowed you down we have, yes? You won’t be having a stroke. But busy I’m sure you are. That last gentleman, Leutnant Carstairs, the criminals said were taking over.” There were little soft zs where the th sounds should have been. And Leutnant. Wasn’t that German? “Relax that man could not.”

“Carstairs, ma’am?” Cash asked.

“A long time ago was that. Years. Now. I can do for you what?”

Accent and rhythm were moving more toward the Missourian, though her compound and complex sentences remained confusing.

There were concepts of feminine delicacy which went with the age into which they had plunged, concepts especially strong as regarded little old ladies. But in their business they weren’t accustomed to dealing with murder delicately. “Our officers found a man in the alley last night,” Cash said. “Dead.”

“Himmel!” One tiny hand covered her mouth momentarily.

“We’re asking everyone if they heard or saw anything.”

“No. Though Tom was restless. The weather it was, I thought.”

“Tom?”

She indicated the cat, who sat at her feet eying the cream pitcher.

“I see. Just one more thing, then. We have to ask you to look at this picture....”

“Not to be so apologetic, young man. Please to let me see it.”

Cash handed it to her, said, “No one knows who he is.”

There were a lot of things the department didn’t know, he reflected. Like how the guy died. Forensics, the coroner, and fingerprint people were all working on him.

She stiffened, grew pale.

“You know him?” Cash asked, hoping he had struck oil.

“No. For a moment I thought... He looks like a man I knew a long time ago. Before you were born, probably.”

Indian Head pennies and a corpse that was an utter mystery to everyone except, possibly, an old lady who said he looked like someone she had known before he was born. Not much to go on.

“Well, thanks for your time and the tea,” Cash said. “We really do have to get on.”

“Welcome, Sergeant.” She accompanied them to the door, an aged but spritely gnome in Cash’s imagination.

“You think she knows s

omething?” Harald asked as they approached the four-family flat next door.

Cash shrugged. “I think she told the truth.” But he had reservations.

John glanced at her house. “Spooky place.”

“I sort of liked it.”

“Figured you would.”

They struck out everywhere.

“The prelims are in,” Lieutenant Railsback told them when they returned to the station. “We’ve still got a John Doe.”

“Give them time,” said Cash. “FBI won’t even be awake yet.”

“Christ, it’s hot in here,” John complained. “Can’t you turn it down? What ever happened to the energy crisis?”

Railsback was one of those people who set the thermostat at eighty, then opened windows.

The lieutenant ignored Harald, one of his favorite pastimes. “You ain’t going to believe the coroner.”

“What’d hesay?”

Railsback lit up. It had been two years, but Cash still lusted after the weed.

“The guy was scared to death. Ain’t that a bite in the ass? And he was dead less than an hour when they found him.”

“Any marks?” Harald asked.

“On his back. Maybe fingernail scratches.”

“Cherchez la femme.”

“Eh? Damned college kids....”

“Means find the woman. He was a Jody. Somebody’s old man got home early.”

“And scared him to death?”

“Maybe he was the nervous type.”

Cash intervened before the dispute could heat up. “I don’t think it’ll hold water, John, but it’s an angle. Let’s see what Smith and Tucholski got.” The detectives who had worked the Shaw side of the block, he saw, had been back long enough to get the red out of their cheeks. Long enough for Tucholski, who looked like a slightly younger Richard Daley, to have fouled half the office with dense blue cigar smoke. Smith defended himself by chain-smoking Kools. Officer Beth Tavares, who was little more than secretary-receptionist for the squad, coughed and scowled their way.