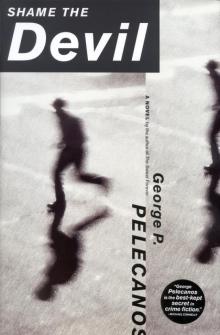

Shame the Devil

George Pelecanos

Copyright © 2000 by George P. Pelecanos

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at www.HachetteBookGroup.com

www.twitter.com/littlebrown

The characters and events in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

ISBN: 978-0-316-07380-6

Contents

Copyright Page

WASHINGTON, D.C. JULY 1995

ONE

TWO

WASHINGTON, D.C. JANUARY 1998

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

NINETEEN

TWENTY

TWENTY-ONE

TWENTY-TWO

TWENTY-THREE

TWENTY-FOUR

TWENTY-FIVE

TWENTY-SIX

TWENTY-SEVEN

TWENTY-EIGHT

TWENTY-NINE

THIRTY

THIRTY-ONE

THIRTY-TWO

THIRTY-THREE

THIRTY-FOUR

THIRTY-FIVE

THIRTY-SIX

THIRTY-SEVEN

THIRTY-EIGHT

WASHINGTON, D. C. JULY 1998

THIRTY-NINE

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ALSO BY GEORGE P. PELECANOS

The Sweet Forever

King Suckerman

The Big Blowdown

Down By the River Where the Dead Men Go

Shoedog

Nick’s Trip

A Firing Offense

FOR EMILY

WASHINGTON, D.C.

JULY 1995

ONE

THE CAR WAS a boxy late-model Ford sedan, white over black, innocuous bordering on invisible, and very fast. It had been a sheriff’s vehicle originally, bought at auction in Tennessee, and further modified for speed.

The car rolled north on Wisconsin beneath a blazing white sun. The men inside wore long-sleeved shirts, tails out. Their shirtfronts were spotted with sweat and their backs were slick with it. The black vinyl on which they sat was hot to the touch. From the passenger seat, Frank Farrow studied the street. The sidewalks were empty. Foreign-made automobiles moved along quietly, their occupants cool and cocooned. Heat mirage shimmered up off asphalt. The city was narcotized — it was that kind of summer day.

“Quebec,” said Richard Farrow, his gloved hands clutching the wheel. He pushed his aviator shades back up over the bridge of his nose, and as they neared the next cross street he said, “Upton.”

“You’ve got Thirty-ninth up ahead,” said Frank. “You want to take that shoot-off, just past Van Ness.”

“I know it,” said Richard. “You don’t have to tell me again because I know.”

“Take it easy, Richard.”

“All right.”

In the backseat, Roman Otis softly sang the first verse to “One in a Million You,” raising his voice just a little to put the full Larry Graham inflection into the chorus. He had heard the single on WHUR earlier that morning, and the tune would not leave his head.

The Ford passed through the intersection at Upton.

Otis looked down at his lap, where the weight of his shotgun had begun to etch a deep wrinkle in his linen slacks. Well, he should have known it. All you had to do was look at linen to make it wrinkle, that was a plain fact. Still, a man needed to have a certain kind of style to him when he left the house for work. Otis placed the sawed-off on the floor, resting its stock across the toes of his lizard-skin monk straps. He glanced at the street-bought Rolex strapped to his left wrist: five minutes past ten A.M.

Richard cut the Ford up 39th.

“There,” said Frank. “That Chevy’s pulling out.”

“I see it,” said Richard.

They waited for the Chevy. Then Frank said, “Put it in.”

Richard swung the Ford into the space and killed the engine. They were at the back of a low-rise commercial strip that fronted Wisconsin Avenue. The door leading to the kitchen of the pizza parlor, May’s, was situated in the center of the block. Frank wiped moisture from his brush mustache and ran a hand through his closely cropped gray hair.

“There’s the Caddy,” said Otis, noticing the black DeVille parked three spaces ahead.

Frank nodded. “Mr. Carl’s making the pickup. He’s inside.”

“Let’s do this thing,” said Otis.

“Wait for our boy to open the door,” said Frank. He drew two latex examination gloves from a tissue-sized box and slipped them over the pair he already had on his hands. He tossed the box over his shoulder to the backseat. “Here. Double up.”

Roman Otis raised his right hand, where a silver ID bracelet bearing the inscription “Back to Oakland” hung on his wrist. He let the bracelet slip down inside the French cuff of his shirt. He put the gloves on carefully, then reflexively touched the butt of the .45 fitted beneath his shirt. He caught a glimpse of his shoulder-length hair, recently treated with relaxer, in the rearview mirror. Shoot, thought Otis, Nick Ashford couldn’t claim to have a finer head of hair on him. Otis smiled at his reflection, his one gold tooth catching the light. He gave himself a wink.

“Frank,” said Richard.

“We’ll be out in a few minutes,” said Frank. “Don’t turn the engine over until you see us coming back out.”

“I won’t,” said Richard, a catch in his voice.

The back kitchen door to May’s opened. A thin black man wearing a full apron stepped out with a bag of trash. He carried the trash to a Dumpster and swung it in, bouncing it off the upraised lid. On his way back to the kitchen he eye-swept the men in the Ford. He stepped back inside, leaving the door ajar behind him.

“That him?” asked Otis.

“Charles Greene,” said Frank.

“Good boy.”

Frank checked the .22 Woodsman and the .38 Bulldog holstered beneath his oxford shirt. The guns were snug against his guinea-T. He looked across the bench at his kid brother, sweating like a hard-run horse, breathing through his mouth, glassy eyed, scared stupid.

“Remember, Richard. Wait till you see us come out.”

Richard Farrow nodded one time.

Roman Otis lifted the shotgun, slipped it barrel down into his open shirt, fitting it in a custom-made leather holster hung over his left side. It would show; there wasn’t any way to get around it. But they would be going straight in, and they would move fast.

“Let’s go, Roman,” said Frank.

Otis said, “Right.” He opened the car door and touched his foot to the street.

“C’mon,” said Lisa Karras, “put your arms up, Jimmy.”

Lisa’s son raised his hands and then dropped them as she tried to fit the maroon-and-gold shirt over his head. He wiggle-wormed out of the shirt, giggled as he backed up against a scarred playroom wall. Looking at him, Lisa laughed too.

There were mornings when she would be trying to get him off to school or get herself to an appointment and Jimmy would keep pushing her buttons until she’d lose her temper in a big way. But this was not one of those mornings. Jimmy had been out of kinder

garten since June, and Lisa had not picked up any freelance design work in the last month. This was just a slow morning on a hot summer day. The two of them had nothing but time.

“Hey, kiddo, I thought you said you wanted some ice cream.”

Jimmy Karras zoomed over and raised his arms. Lisa got the short-sleeved Redskins jersey on him before he had a chance to squirm out of it, then sat him down and fitted a pair of miniature Vans sneakers on his feet.

“Double knots, Mom.”

“You got it.”

Jimmy stood up and raced off. He skipped once, something he did without thought when he was happy, on the way to the door.

Ice cream at ten A.M. Lisa almost laughed, thinking of what her peers would have to say about that. Most of the other mothers in the neighborhood were content to sit their kids down in front of the television set on hot days like this. But Lisa couldn’t stand to be in the house all day, no matter the weather. And she knew that Jimmy liked to get out too. A trip to the ice cream store would be just fine.

Jimmy stood on his toes at the front door, trying to turn the lock. A rabbit’s foot hung from a key chain fixed to a belt loop of his navy blue shorts. The rabbit’s foot was white and gray, with toenails curling out of the fur. Lisa had given her husband, Dimitri, a few sharp words when he had brought it home from the surplus store, but she had let the matter drop when she saw her son’s eyes widen at the sight of it. The rabbit’s foot was one of those strange items — pocket-knives, lighters, firecrackers — that held a mutual fascination for fathers and sons. She had long since given up on trying to understand.

“Help me, Mom.”

“You got it.”

She rested the flat of her palm on his short, curly brown hair as she turned the lock. His scalp was warm to the touch.

“Mom, can we go for a Metro ride today?”

“One thing at a time, okay, honey?”

“Could we take the Metro to the zoo?”

“I don’t think so. Anyway, it’s too hot. The animals will all be inside.”

“Aw,” said Jimmy, flipping his hand at the wrist. “Gimme a break!”

Jimmy ran down the concrete steps as she locked the front door of the colonial. She watched him bolt across the sidewalk and head toward the street.

“Jimmy!” she yelled.

Jimmy stopped short of the street at the sound of her voice. He turned, pointing at her and laughing, his eyes closed, his dimples deeply etched in a smooth oval face.

Mrs. Lincoln, the old woman next door, called from her porch, “You better watch that boy!”

Lisa smiled and said cheerfully, “He’s a handful, all right.” And under her breath she added, “You dried-up old crow.”

As Lisa got down to the sidewalk of Alton Place, Jimmy said, “What’d you say, Mom?”

“Just saying hello to Mrs. Lincoln.”

“You mean Mrs. Stinkin’?”

“Now, don’t you ever say that except in our house, honey. Daddy was just kidding when he made up that name for her. It’s not nice.”

“But she does smell funny, though.”

“Old people have a different smell to them, that’s all.”

“She smells.”

“Jimmy!”

“Okay.”

They walked a bit. They stopped at the corner of 38th Street, and Jimmy said, “Where we goin’ for ice cream, Mom?”

“That store next to the pizza parlor.”

“Which pizza parlor?” said Jimmy.

“You know,” said Lisa Karras. “May’s.”

Roman Otis went in first, putting a hard shoulder to the door. Frank Farrow stepped in next, cross-drawing the .22 and the .38 revolver at once. He kicked the door shut behind him as Otis drew the sawed-off and pumped a shell into the breech.

“All right,” said Otis. “Don’t none a y’all move.”

Charles Greene, the pizza chef, stood still behind the kitchen’s stainless steel prep table and raised his hands. Mr. Carl, a short man with a stub of unlit cigar wedged in the side of his liver-lipped mouth, stood to the side of the table. On the tiled floor beside him sat an olive green medium-size duffel bag, zipped shut.

“What is this?” said Mr. Carl, direct and calm, looking at the armed white man with the gray hair.

Frank up-jerked the .38. “Raise your hands and shut your mouth.”

Carl Lewin raised his arms very slowly, careful not to let his sport jacket spread open and reveal the .32 Davis he carried wedged against his right hip on pickup day.

“Against the wall,” said Frank.

Greene and Mr. Carl moved back. Frank holstered the .22, stepped over to the duffel bag, and opened it. He had a quick look inside at the stacks of green: tens, twenties, and hundreds, loosely banded. He ran the zipper back up its neck and nodded at Otis.

“Okay, pizza man,” said Otis. “Who we got in the front of the house?”

Charles Greene licked his dry lips. “The bartender. And the day waiter’s out in the dining room, setting up.”

“Go out there and bring the waiter back with you,” said Otis. “Don’t be funny, neither.” Greene hesitated, and Otis said, “Go on, boy. Let’s get this over with so we can all be on our way.”

Greene had a look at Mr. Carl before hurrying from the kitchen. Mr. Carl stared at the gray-haired white man without speaking. Then they heard footsteps returning to the kitchen and a chiding young voice saying, “What could be so important, Charlie? I’ve got side work.”

The waiter, who was named Vance Walters, entered the kitchen with Greene behind him. At the sight of the men and their guns, Walters nearly turned to run, then swallowed and breathed out slowly. The moment had passed, and now it was too late. He wondered, as he always did, what his father would have done in a situation such as this one. He raised his hands without a prompt. If he’d just cooperate, they wouldn’t hurt him, whoever they were.

“What’s your name?” said Frank.

“Vance,” said the waiter.

“Over there against the wall with your boss,” said Frank.

Otis watched the waiter with the perfect springy haircut hurry around the prep table. One of those light-steppin’ mugs. Vance with the tight-ass pants. Otis knew the look straight away. Marys like Vance got snatched up on the cell block right quick.

“I’ll get the bartender,” said Frank to Otis.

Frank Farrow left the kitchen. Otis pointed the shotgun at each of the three men against the wall in turn. He began to sing “One in a Million You” under his breath. As he sang, he smiled at Mr. Carl.

Detective William Jonas cruised up Wisconsin in his unmarked and made the turn up 39th. The cold air felt good blowing against his torso, and for a change he was fairly relaxed. It wasn’t often that he rolled on the clean, white-bread streets of upper Northwest’s Ward 3. Most of his action was in neighborhoods like Trinidad, Pet-worth, LeDroit Park, and Columbia Heights. But this morning he had an interview with a teenage kid who worked at the chain video store over near Wilson High. The kid lived in Shaw, and he had grown up with a couple of young citizens charged with beating a pipehead to death outside a plywood-door house east of 14th and Irving. Jonas hated to roust the kid at work, but the young man had been uncooperative on his home turf. Jonas figured that the kid would talk, and talk quick, at his place of employment.

William Jonas had two sons at Wilson himself. They took the bus across town from Jonas’s house on Hamlin Street, over in Brookland.

It wouldn’t be too long before he had his boys in college and could retire his shield. The money was already put away for their schooling. He’d been saving on an automatic-withdrawal plan since they were boys. Thank the good Lord for blue chips. With his pension and the house damn near 75 percent paid off, he and Dee could enjoy themselves for real. He’d be in his middle fifties by then — retired and still a relatively young man. But it was a little early to be dreaming on it. He had a few years left to go.

As he went slowly up 39th, Jonas n

oticed a parked car on his right, looked almost like an old cop car, with a man behind the wheel, sitting there with all four windows rolled down. The man was pockmarked and sweating something awful; his sunglasses slipped down to the end of his nose as he bent forward, trying to put a match to a cigarette. Looked like his hand was shaking, too, and… damn if he wasn’t wearing some kind of rubber gloves. As Jonas passed, the man glanced out the window and quickly averted his eyes. In the rearview Jonas saw Virginia plates on the front of the car — a Merc, maybe. No, he could see the familiar blue oval on the grillwork: a Ford.

Veazy Street, Warren, Windom… Now that had to be the only car he’d seen all morning with the windows down on a hotter-than-the-devil day like today. Everyone else had their air-conditioning on full, and what car didn’t have air-conditioning these days? And the man behind the wheel, white like everyone in this neighborhood but still not like them, had seemed kind of nervous. Like he didn’t belong there. Wearing those gloves, too. Twenty-five years on the force and Bill Jonas knew.

He had a few minutes before his interview with the video-store kid. Maybe he’d cruise around the block, give that Ford another pass.

Richard Farrow hotboxed his smoke while watching the black car hang a left a few blocks up 39th. Any high school kid with an ounce of weed in his glove box would have spotted the unmarked car. And the driver, some kind of cop, had given him the fish-eye as he passed.

The question was, Was the black cop in the black car going to come around the block and check him out again?

Richard touched the grip of the nine millimeter tucked between his legs. The way he had it, snug up against his rocks and pressing on his blue jeans, it had felt good. But now the sensation faded. He grabbed the Beretta and tapped the barrel against his thigh. He dragged hard on his cigarette and flicked the butt out to the street.

God, it was hot.

What the fuck was he doing here, anyway? Sure, he’d done his share of small-time boosts — car thefts, smash-and-grabs, like that — with his older brother when they were in their teens. Back between Frank’s reform school years and his first four-year jolt. Then Frank got sent up for another eight, and during that time Richard went from one useless job to the next, fighting his various addictions — alcohol, crystal meth, coke, and married women — along the way. The funny thing was, when Frank got out of the joint the last time, he was smarter, tougher, and more connected than Richard would ever be. Yeah, crime and prison had been good to Frank. So when Frank had phoned and asked his little brother if he would be interested in a quick and easy score that he and Otis were about to pull off, Richard had said yes. He saw it as a last chance to turn his life around. And to be on a level playing field — to be a success, for once — with Frank.