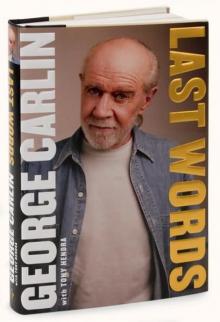

Last Words

George Carlin

CONTENTS Introduction by Tony Hendra ix

1 The Old Man and the Sunbeam 1

2 Holy Mary, Mother of George 15

3 Curious George 23

4 The Ace of Aces and the Dude of Dudes 41

5 Air Marshal Carhn Tells You to Go Fuck Yourself 51

6 Two Guys in Their Underwear 67

7 Introducing the Very Lovely, Very Talented—Brenda! 85

8 Those Fabulous Sixties 97

9 Inside Every Silver Lining There's a Dark Cloud 117

10 The Long Epiphany 135

11 Wurds, Werds, Words 155

12 High on the Hill 175

13 Say Goodbye to George Carlin 191

14 Death and Taxes 209

15 I Get Pissed, Goddamit! 223

16 Working Rageaholic 241

17 Doors Close, Doors Open 259

18 Being, Doing, Getting 277

19 New York Boy 289

"Gee, he was here a moment ago . . ."

— (What George wanted on his tombstone—

if he'd had one.)

INTRODUCTION

Tony Hendra

I have this real moron thing I do? It's called thinking.

- G C

For the last half century, somewhere in America, night in

night out, George Carlin stood on a stage, raging, explaining, berating, sniping, purring questions, snarling answers,

kicking holes in the polyester pants of hypocrisy, puking down the

nice clean tux of conventional wisdom, doing what none of the interchangeable comics who shuffle across Comedy Central's various interchangeable performance areas ever do: "this real moron

thing—thinking."

A mild-mannered and approachable man offstage, the riled-up,

baffled Everyman he played onstage was the final step in the evolution of an intelligence that, like no other, got under the skin of the

American Dream.

"It's called the American Dream because to believe it, you have

to be ASLEEP!"

All his life he yanked the Band-Aids off that bruised and battered

carcass, and poked savagely away at what he found underneath. In

the seventies he did it by probing his own history in classic works

like Class Clown, becoming a prime mover in a kind of comedy

saddled with the term "nostalgia" but which was actually something

far more interesting and ambivalent, fond memories of absurd repression. During the Reagan imperium his attention began turning outward to politics, violence, language, especially official and

pseudo-official language, not to mention that central social issue,

INTRODUCTION

pets. In the nineties and the Bush years—the zeros—he took on

more general symptoms of the folly of his species: war, religion, the

planet, consumerism, cataclysm, death, divinity, golf.

Unlike many of his peers, he died uncorrupted, uncompromised

and unbowed. He was urban not suburban, live not prerecorded,

raw not precooked. His voice always vibrated with the energy of

the Harlem streets from which he sprang, cutting through middleclass crap like a fine old ivory-handled straight razor. Because he

did this alone, without fanfare, live, often in lowbrow locales like

blue-collar clubs and Las Vegas, the proposition that George Carlin was a major artist may raise the brows, even the hackles, of the

artist-ocracy. But that is what he became in his maturity: a unique

creative force, equal parts actor, philosopher, satirist, poet—a real

man of the people, not a multimillionaire media travesty of one. An

artist whose designation "comedian" describes his work as inadequately as "painter" describes Francis Bacon or "guitarist" describes

B.B. King.

It isn't the purpose of this book to make that case, though I have

tried to shape the narrative—as far as another's first-person narrative

can be shaped—to show how an acutely perceptive young performer

with an ear as sharp as surgical steel became first an accomplished

writer, then a master craftsman and finally a mature artist who

could not only make you laugh till you were gasping but then take

your breath away once you'd caught it, with the hard-edged poetry

and coruscating variety of his language. No one I ever met in the

business of being funny, and I've met a few, was more the antithesis

of Happy the Carefree Clown than George; no one understood better that comedy at its finest is a dark and beautiful art.

For me this book is first and foremost a labor of love. More than

fifteen years ago George asked me to help him tell the story of his

life, and for a variety of mostly logistical reasons, I never got to finish

the job. And while George told many bits and pieces of his story to

various people at various times, he always wanted to get the whole

thing down in one place at one time, packaged, polished and perfect. He made no secret of being anal in his habits, and he liked his

works put away neat and tidy up on the shelf of his lifetime achievex

INTRODUCTION

ments. This book is one of the very few that never made it up there.

Until now.

I first met George in mid-1964 when he was starting out as a comedian and I was too (actually half of one: my partner Nick Ullett

and I were a comedy team). It was in the legendary, if unfortunately

named, Café Au Go Go on Bleecker Street in Greenwich Village. The Go Go was Greenwich Village in the sixties. Grotty and

gloomy, with black walls and a bare-board stage, it was dark enough

that at a corner table, you could actually suck on a furtive joint.

Music greats as diverse as Stan Getz and the Blues Project recorded

classic albums there, folkies like Stephen Stills transitioned into

rockers there, up-and-coming comedians like Richard Pryor and

Lily Tomlin cut their comedie milk-teeth there.

George was one of them: the Go Go was his New York base—"my

laboratory." Off and on for a year, he'd been developing material for

what would soon be an Apollo mission of a television career. Nick

and I had also appeared at the Go Go a couple of times, notably

opening for Lenny Bruce earlier in the year. It had been our first

booking in America—and a delightful introduction to America it

was. The third night of the gig, undercover NYPD cops arrested

Lenny as he came off stage—allegedly for obscenity but as likely for

being too funny about Catholics. He made bail and went back to

work the next night with the same act. So the next week they busted

him all over again.

The Go Go was one bond with George; Lenny was another. We'd

gotten to know him quite well during his disastrous run; and Lenny

had given George his start in showbiz four years earlier when he too

had been half of a comedy team (with TV producer Jack Burns).

We all idolized Lenny's brilliant, risk-taking material, the Zorro-like

satiric slashes he left on the asses of his targets. Lenny was who we

all wanted to be when we grew up.

Throughout the rest of the sixties George and we were friendly

competitors. We played the same nightclubs as he did across

America—Mister Kelly's in Chicago, the hungry i in San Francisco. We got our first TV break like him, on the old Merv

G r i f f i n

XI

INTRODUCTION

Show. We endured the same vapid wasteland of sixties variety TV—

especially the purgatorial torments of The Ed Sullivan Show. Shows

that censored out all mention of the social turmoil and revolutionary tumult going on outside their studio doors.

George was a hit in the wasteland (more than us), but the repressive environment triggered in him—and me—a major selfreinvention as the sixties became the seventies. George transformed

into the groundbreaking satiric stand-up we knew and loved; I

signed on as an original editor of the brand-new humor magazine

National Lampoon. Again we were competitors—this time for the

vast campus audience the Baby Boom had created. The only time I

saw George now was in Atlantic Records' ads for his comedy albums

in our pages; they were often next to house ads for the Lampoons

own hit comedy albums, the first two of which I produced. Then,

for a decade, our paths diverged.

In the mideighties, I took a sabbatical from satire to write about

satire: a book called Going Too Far, dealing with the antiestablishment humor that had emerged in the midfifties and given rise in

the sixties and seventies to an extraordinary generation of comedic

voices. In an unguarded moment I described this to my editor as

"Boomer humor"; he insisted I use the wretched term throughout

the book. Among the many comedy stars I wanted to interview,

George was by now in the top rank.

George best typified a crucial element of my premise: that

Boomer humor—because of its fundamental message of dissenthad always had an adversarial relationship with Official America's

most powerful weapon, television. In its origins it had tended to be a

humor of the page or the stage—whether concert, nightclub or theater. A live, largely uncensored affair, often improvised and by definition unrepeatable, the very opposite of recorded entertainment.

To get it, you hadda be there.

Like a few other major comedians—Richard Pryor, Lily Tomlin,

Steve Martin—George had remained faithful to this principle, working almost exclusively in live performance since the early seventies,

appearing on television only as "an advertisement for myself." His

most notorious comic essay, "Seven Words You Can Never Say on

Xll

INTRODUCTION

Television," deftly defined the antagonism—and Boomer humor's

core appeal. And he'd stuck to his guns—except for a brief lapse in

the late seventies when he was at risk of becoming Johnny Carson's

doppelganger. By the mideighties he was almost alone among major

comedians who still worked live all the time.

For George the stage hadn't been stasis or stagnation. Quite the

contrary: the uncensored freedom of live performance was what fed

his ever-broadening and deepening work, gave it such flair, range

and demotic force. He sharpened his art for and with real people,

not the anonymous zero of a camera lens. He disseminated his

comic vision by spoken word, gesture, inflection, the raised shoulder or eyebrow, the pause, the beat, the word not spoken, all those

elements of performance the camera cheapens, falsifies or simply

misses. He was building a devoted following of millions, a few thousand at a time. He had learned that laughter, like politics, is always

local. To get George, you hadda be there.

And George gave good interview. He was the most articulate of

all my subjects about his craft, his artistic development and his comedic view of the world. Furthermore, his life onstage and off were

one and the same. This was a man who lived through his craft and

his material.

Even with giants of Boomer humor like Dick Gregory or Jules

Feiffer, my interviews usually ran around an hour. With George we

became so engrossed in our conversation that we recorded cassette

after cassette over a period of a week or more, covering his development from his childhood in wartime Manhattan to the movie he'd

just completed ( O u t r a g e o u s Fortune, starring Bette Midler): a more

than forty-year period for which his recall was phenomenal.

Great for my book. Far more exciting though was discovering,

after a decade in very different areas of comedy, how much we

had in common. We'd both had Catholic backgrounds, we were

both loners obsessed with the nature and practice of comedy.

We shared comic loves, hates, preferences, insights and experiences, for instance those ghastly sixties variety shows. (There was

no one in my rather literary comedic circle with whom I could share

the terror recollected in tranquillity, oiThe Ed Sullivan Show.) This

x i i i

INTRODUCTION

time around we weren't just professional colleagues. We really hit it

off. And laughed a lot.

George turned fifty in 1987 and soon after caught the autobiography bug. In 1992 he asked me to read what he'd written so far.

He wasn't happy with it. "It" was a hundred double-spaced pages

covering the first six years of his life in copious, often funny detail, interlarded with many rather self-consciously "writerly" passages. The hundred pages were continuous: they were the opening

chapter. I pointed out that by this math, his first sixty years would

run a thousand pages. Even in an era of morbidly obese memoirs it

would stand out. That was why I was reading the fucking thing, said

George. He needed someone to help.

So began the long, wild, meandering, erratic and almost always

hilarious process of documenting the life, times and oeuvre of

George Denis Patrick Carlin. I already had ten to twelve hours of

great stuff from Going Too Far. Over the next ten years we added

forty to fifty hours more of taped conversations and as many unrecorded ones. It was an unpredictable process. Right after we'd done

our initial sessions, I became editor in chief of Spy and George went

into preproduction on his Fox sitcom, The George Carlin Show.

Work was limited to spur-of-the-moment meetings when we happened to be in the same city. After a year, Spy expired, followed not

long after by The George Carlin Show. Work resumed—the body of

material grew both on tape and other notes and I began to rough out

some early chapters.

The genre of what we were creating, since it intersected somewhat with our modus, came up. George didn't want to call it an

autobiography: only pinheaded criminal business pricks and politicians wrote autobiographies. We also tossed the narcissistic Gallicism "memoir," which we decided was a linguistic mongrel of "me"

and "moi." Because George wanted to place himself in the context

of important movements in comedy over what was nearly a forty-year

career, I started adding interstitial pieces of that cultural history. So

a few years in, with a book emerging that was part biography, part

autobiography, we hit on our genre: it was George's sortabiography.

And that's what we called it ever after.

X I V

INTRODUCTION

In early April 1997, George's wife Brenda was diagnosed with terminal liver cancer. She declined rapidly and died just five weeks

later, the day before George's sixtieth birthday. Partly because she

had figured fairly prominently in the sortabiography, partly because

of the yearlong depression he went through in

the aftermath, we put

it aside for a while. That year he also published his first hardback humor book, Brain Droppings. It was a big best-seller and George relished the role of author. He began planning a second book, Napalm

6- Silly Putty. We'd get to the sortabiography, all in good time. We

continued to see each other in our normal ad hoc way, discussing

new developments in his life and work for possible inclusion and

refining what we already had.

Napalm (5 Silly Putty was to come out in late April 2001. Part of

the planned launch was an event at the Writers Guild Theater in

L.A., one of a prestigious lecture series called Writers Bloc. George

asked me to do the evening with him as an onstage conversation

about the book, but also about his life and work. We set the intellectual bar quite high—the audience included a number of distinguished members of the WGA—and after some initial discomfort,

relaxed into a fascinating dialogue. As it developed, both of us realized the same thing: we were good at this because we'd been doing

it for years. It was a public version of the free-ranging conversations

we'd had about the sortabiography, which would often take us to

completely unexpected places. The audience seemed to enjoy the

ride and the evening was a success. (Though the distinguished

Writers' questions didn't quite make it over our intellectual bar:

"What do you watch on TV?" was one; "What do you think of the

current crop of comedians?" was another.)

The experience put the sortabiography back front and center and

we began discussing doing it as George's next book. This back-andforth generated a classic George Moment.

He usually initiated contact with me by sending me an e-mail

of mind-bending prurience. Whenever I saw on AOL the screen

name "sleetmanal" (for A1 Sleet, the Hippy-Dippy Weatherman) I knew I was in for some truly revolting images. I would try

to top him and disgusting e-mails went back and forth until we'd

X V

INTRODUCTION

decided on a place and time to meet or to have a phone conference.

This time George decided to cold-call my New York apartment.