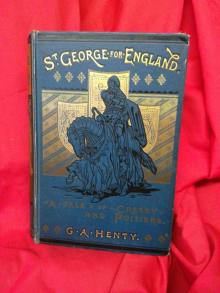

St. George for England

G. A. Henty

Produced by Martin Robb

SAINT GEORGE FOR ENGLAND

By G. A. Henty

PREFACE.

MY DEAR LADS,

You may be told perhaps that there is no good to be obtained from talesof fighting and bloodshed,--that there is no moral to be drawn from suchhistories. Believe it not. War has its lessons as well as Peace. Youwill learn from tales like this that determination and enthusiasmcan accomplish marvels, that true courage is generally accompanied bymagnanimity and gentleness, and that if not in itself the very highestof virtues, it is the parent of almost all the others, since but fewof them can be practised without it. The courage of our forefathers hascreated the greatest empire in the world around a small and in itselfinsignificant island; if this empire is ever lost, it will be by thecowardice of their descendants.

At no period of her history did England stand so high in the eyesof Europe as in the time whose events are recorded in this volume. Achivalrous king and an even more chivalrous prince had infected thewhole people with their martial spirit, and the result was that theirarmies were for a time invincible, and the most astonishing successeswere gained against numbers which would appear overwhelming. Thevictories of Cressy and Poitiers may be to some extent accounted for bysuperior generalship and discipline on the part of the conquerors; butthis will not account for the great naval victory over the Spanish fleetoff the coast of Sussex, a victory even more surprising and won againstgreater odds than was that gained in the same waters centuries laterover the Spanish Armada. The historical facts of the story are alldrawn from Froissart and other contemporary historians, as collatedand compared by Mr. James in his carefully written history. They maytherefore be relied upon as accurate in every important particular.

Yours sincerely,

G. A. HENTY.

CHAPTER I: A WAYFARER

It was a bitterly cold night in the month of November, 1330. The rainwas pouring heavily, when a woman, with child in her arms, entered thelittle village of Southwark. She had evidently come from a distance, forher dress was travel-stained and muddy. She tottered rather than walked,and when, upon her arrival at the gateway on the southern side of LondonBridge, she found that the hour was past and the gates closed for thenight, she leant against the wall with a faint groan of exhaustion anddisappointment.

After remaining, as if in doubt, for some time, she feebly made her wayinto the village. Here were many houses of entertainment, for travelerslike herself often arrived too late to enter the gates, and had to abideoutside for the night. Moreover, house rent was dear within the walls ofthe crowded city, and many, whose business brought them to town, foundit cheaper to take up their abode in the quiet hostels of Southwarkrather than to stay in the more expensive inns within the walls. Thelights came out brightly from many of the casements, with sounds ofboisterous songs and laughter. The woman passed these without a pause.Presently she stopped before a cottage, from which a feeble light aloneshowed that it was tenanted.

She knocked at the door. It was opened by a pleasant-faced man of somethirty years old.

"What is it?" he asked.

"I am a wayfarer," the woman answered feebly. "Canst take me and mychild in for the night?"

"You have made a mistake," the man said; "this is no inn. Further up theroad there are plenty of places where you can find such accommodation asyou lack."

"I have passed them," the woman said, "but all seemed full ofroisterers. I am wet and weary, and my strength is nigh spent. I can paythee, good fellow, and I pray you as a Christian to let me come in andsleep before your fire for the night. When the gates are open inthe morning I will go; for I have a friend within the city who will,methinks, receive me."

The tone of voice, and the addressing of himself as good fellow, at onceconvinced the man that the woman before him was no common wayfarer.

"Come in," he said; "Geoffrey Ward is not a man to shut his doors ina woman's face on a night like this, nor does he need payment for suchsmall hospitality. Come hither, Madge!" he shouted; and at his voice awoman came down from the upper chamber. "Sister," he said; "this is awayfarer who needs shelter for the night; she is wet and weary. Do youtake her up to your room and lend her some dry clothing; then make hera cup of warm posset, which she needs sorely. I will fetch an armfulof fresh rushes from the shed and strew them here: I will sleep in thesmithy. Quick, girl," he said sharply; "she is fainting with cold andfatigue." And as he spoke he caught the woman as she was about to fall,and laid her gently on the ground. "She is of better station than sheseems," he said to his sister; "like enough some poor lady whose husbandhas taken part in the troubles; but that is no business of ours. Quick,Madge, and get these wet things off her; she is soaked to the skin. Iwill go round to the Green Dragon and will fetch a cup of warm cordial,which I warrant me will put fresh life into her."

So saying, he took down his flat cap from its peg on the wall and wentout, while his sister at once proceeded to remove the drenchedgarments and to rub the cold hands of the guest until she recoveredconsciousness. When Geoffrey Ward returned, the woman was sitting in asettle by the fireside, dressed in a warm woolen garment belonging tohis sister.

Madge had thrown fresh wood on the fire, which was blazing brightly now.The woman drank the steaming beverage which her host brought with him.The colour came faintly again into her cheeks.

"I thank you, indeed," she said, "for your kindness. Had you not takenme in I think I would have died at your door, for indeed I could go nofurther; and though I hold not to life, yet would I fain live until Ihave delivered my boy into the hands of those who will be kind to him,and this will, I trust, be tomorrow."

"Say nought about it," Geoffrey answered; "Madge and I are right gladto have been of service to you. It would be a poor world indeed if onecould not give a corner of one's fireside to a fellow-creature on sucha night as this, especially when that fellow creature is a woman witha child. Poor little chap! He looks right well and sturdy, and seems tohave taken no ill from his journey."

"Truly, he is well and sturdy," the mother said, looking at him proudly;"indeed I have been almost wishing today that he were lighter by a fewpounds, for in truth I am not used to carry him far, and his weight hassorely tried me. His name is Walter, and I trust," she added, looking atthe powerful figure of her host, "that he will grow up as straight andas stalwart as yourself." The child, who was about three years old,was indeed an exceedingly fine little fellow, as he sat, in one scantygarment, in his mother's lap, gazing with round eyes at the blazingfire; and the smith thought how pretty a picture the child and mothermade. She was a fair, gentle-looking girl some two-and-twenty years old,and it was easy enough to see now from her delicate features and softshapely hands that she had never been accustomed to toil.

"And now," the smith said, "I will e'en say good night. The hour islate, and I shall be having the watch coming along to know why I keep afire so long after the curfew. Should you be a stranger in the city,I will gladly act as your guide in the morning to the friends whomyou seek, that is, should they be known to me; but if not, we shalldoubtless find them without difficulty."

So saying, the smith retired to his bed of rushes in the smithy, andsoon afterwards the tired visitor, with her baby, lay down on the rushesin front of the fire, for in those days none of the working or artisanclass used beds, which were not indeed, for centuries afterwards, inusage by the common people.

In the morning Geoffrey Ward found that his guest desired to find oneGiles Fletcher, a maker of bows.

"I know him well," the smith said. "There are many who do a largerbusiness, and hold their heads higher; but Giles Fletcher is wellesteemed as a good workman, whose wares can be depended upon. It isoften said of him that did he take less pains h

e would thrive more; buthe handles each bow that he makes as if he loved it, and finishes andpolishes each with his own hand. Therefore he doeth not so much trade asthose who are less particular with their wares, for he hath to chargea high price to be able to live. But none who have ever bought his bowshave regretted the silver which they cost. Many and many a gross ofarrowheads have I sold him, and he is well-nigh as particular intheir make as he is over the spring and temper of his own bows. Many afriendly wrangle have I had with him over their weight and finish, andit is not many who find fault with my handiwork, though I say it myself;and now, madam, I am at your service."

During the night the wayfarer's clothes had been dried. The cloak was ofrough quality, such as might have been used by a peasant woman; but therest, though of sombre colour, were of good material and fashion. Seeingthat her kind entertainers would be hurt by the offer of money, the ladycontented herself with thanking Madge warmly, and saying that she hopedto come across the bridge one day with Dame Fletcher; then, under theguidance of Geoffrey, who insisted on carrying the boy, she set out fromthe smith's cottage. They passed under the outer gate and across thebridge, which later on was covered with a double line of houses andshops, but was now a narrow structure. Over the gateway across theriver, upon pikes, were a number of heads and human limbs. The ladyshuddered as she looked up.

"It is an ugly sight," the smith said, "and I can see no warrant forsuch exposure of the dead. There are the heads of Wallace, of three ofRobert Bruce's brothers, and of many other valiant Scotsmen who foughtagainst the king's grandfather some twenty years back. But after allthey fought for their country, just as Harold and our ancestors againstthe Normans under William, and I think it a foul shame that men who havedone no other harm should be beheaded, still less that their heads andlimbs should be stuck up there gibbering at all passers-by. There areover a score of them, and every fresh trouble adds to their number; butpardon me," he said suddenly as a sob from the figure by his side calledhis attention from the heads on the top of the gateway, "I am rough andheedless in speech, as my sister Madge does often tell me, and it maywell be that I have said something which wounded you."

"You meant no ill," the lady replied; "it was my own thoughts andtroubles which drew tears from me; say not more about it, I pray you."

They passed under the gateway, with its ghastly burden, and were soon inthe crowded streets of London. High overhead the houses extended, eachstory advancing beyond that below it until the occupiers of the atticscould well-nigh shake hands across. They soon left the more crowdedstreets, and turning to the right, after ten minutes walking, the smithstopped in front of a bowyer shop near Aldgate.

"This is the shop," he said, "and there is Giles Fletcher himself tryingthe spring and pull of one of his bows. Here I will leave you, and willone of these days return to inquire if your health has taken ought ofharm by the rough buffeting of the storm of yester-even."

So saying he handed the child to its mother, and with a wave of the handtook his leave, not waiting to listen to the renewed thanks which hislate guest endeavoured to give him.

The shop was open in front, a projecting penthouse sheltered it from theweather; two or three bows lay upon a wide shelf in front, and severallarge sheaves of arrows tied together stood by the wall. A powerful manof some forty years old was standing in the middle of the shop with abent bow in his arm, taking aim at a spot in the wall. Through an opendoor three men could be seen in an inner workshop cutting and shapingthe wood for bows. The bowyer looked round as his visitor entered theshop, and then, with a sudden exclamation, lowered the bow.

"Hush, Giles!" the lady exclaimed; "it is I, but name no names; it werebest that none knew me here."

The craftsman closed the door of communication into the inner room."My Lady Alice," he exclaimed in a low tone, "you here, and in such aguise?"

"Surely it is I," the lady sighed, "although sometimes I am well-nighinclined to ask myself whether it be truly I or not, or whether this benot all a dreadful dream."

"I had heard but vaguely of your troubles," Giles Fletcher said, "buthoped that the rumours were false. Ever since the Duke of Kent wasexecuted the air has been full of rumours. Then came news of the killingof Mortimer and of the imprisonment of the king's mother, and it wassaid that many who were thought to be of her party had been attacked andslain, and I heard--" and there he stopped.

"You heard rightly, good Giles, it is all true. A week after the slayingof Mortimer a band of knights and men-at-arms arrived at our castle anddemanded admittance in the king's name. Sir Roland refused, for he hadnews that many were taking up arms, but it was useless. The castle wasattacked, and after three days' fighting, was taken. Roland was killed,and I was cast out with my child. Afterwards they repented that theyhad let me go, and searched far and wide for me; but I was hidden in thecottage of a woodcutter. They were too busy in hunting down others whomthey proclaimed to be enemies of the king, as they had wrongfully saidof Roland, who had but done his duty faithfully to Queen Isabella, andwas assuredly no enemy of her son, although he might well be opposed tothe weak and indolent king, his father. However, when the search relaxedI borrowed the cloak of the good man's wife and set out for London,whither I have traveled on foot, believing that you and Bertha wouldtake me in and shelter me in my great need."

"Aye, that will we willingly," Giles said. "Was not Bertha your nurse?and to whom should you come if not to her? But will it please you tomount the stairs, for Bertha will not forgive me if I keep you talkingdown here. What a joy it will be to her to see you again!"

So saying, Giles led the way to the apartment above. There was a screamof surprise and joy from his wife, and then Giles quietly withdrewdownstairs again, leaving the women to cry in each other's arms.

A few days later Geoffrey Ward entered the shop of Giles Fletcher.

"I have brought you twenty score of arrowheads, Master Giles," he said."They have been longer in hand than is usual with me, but I have beenpressed. And how goes it with the lady whom I brought to your door lastweek?"

"But sadly, Master Ward, very sadly, as I told you when I came across tothank you again in her name and my own for your kindness to her. Shewas but in poor plight after her journey; poor thing, she was littleaccustomed to such wet and hardship, and doubtless they took allthe more effect because she was low in spirit and weakened with muchgrieving. That night she was taken with a sort of fever, hot and coldby turns, and at times off her head. Since then she has lain in a highfever and does not know even my wife; her thoughts ever go back to thestorming of the castle, and she cries aloud and begs them to spare herlord's life. It is pitiful to hear her. The leech gives but small hopefor her life, and in troth, Master Ward, methinks that God would dealmost gently with her were He to take her. Her heart is already in herhusband's grave, for she was ever of a most loving and faithful nature.Here there would be little comfort for her--she would fret that her boywould never inherit the lands of his father; and although she knowswell enough that she would be always welcome here, and that Bertha wouldserve her as gladly and faithfully as ever she did when she was hernurse, yet she could not but greatly feel the change. She was tenderlybrought up, being, as I told you last week, the only daughter ofSir Harold Broome. Her brother, who but a year ago became lord ofBroomecastle at the death of his father, was one of the queen's men, andit was he, I believe, who brought Sir Roland Somers to that side. He wasslain on the same night as Mortimer, and his lands, like those of SirRoland, have been seized by the crown. The child upstairs is by rightheir to both estates, seeing that his uncle died unmarried. They willdoubtless be conferred upon those who have aided the young king infreeing himself from his mother's domination, for which, indeed,although I lament that Lady Alice should have suffered so sorely in thedoing of it, I blame him not at all. He is a noble prince and will makeus a great king, and the doings of his mother have been a shame tous all. However, I meddle not in politics. If the poor lady dies, asmethinks is well-nigh certain, Bertha and I will bri

ng up the boy as ourown. I have talked it over with my wife, and so far she and I are not ofone mind. I think it will be best to keep him in ignorance of his birthand lineage, since the knowledge cannot benefit him, and will but renderhim discontented with his lot and make him disinclined to take to mycalling, in which he might otherwise earn a living and rise to be arespected citizen. But Bertha hath notions. You have not taken a wife toyourself, Master Geoffrey, or you would know that women oft have fancieswhich wander widely from hard facts, and she says she would have himbrought up as a man-at-arms, so that he may do valiant deeds, and winback some day the title and honour of his family."

Geoffrey Ward laughed. "Trust a woman for being romantic," he said."However, Master Fletcher, you need not for the present trouble aboutthe child's calling, even should its mother die. At any rate, whether hefollows your trade, or whether the blood in his veins leads him to taketo martial deeds, the knowledge of arms may well be of use to him, and Ipromise you that such skill as I have I will teach him when he growsold enough to wield sword and battle-axe. As you know I may, withoutboasting, say that he could scarce have a better master, seeing that Ihave for three years carried away the prize for the best sword-playerat the sports. Methinks the boy will grow up into a strong and stalwartman, for he is truly a splendid lad. As to archery, he need not go farto learn it, since your apprentice, Will Parker, last year won the prizeas the best marksman in the city bounds. Trust me, if his tastes liethat way we will between us turn him out a rare man-at-arms. But I muststand gossiping no longer; the rumours that we are likely ere long tohave war with France, have rarely bettered my trade. Since the wars inScotland men's arms have rusted somewhat, and my two men are hard atwork mending armour and fitting swords to hilts, and forging pike-heads.You see I am a citizen though I dwell outside the bounds, because houserent is cheaper and I get my charcoal without paying the city dues. So Ican work somewhat lower than those in the walls, and I have good customfrom many in Kent, who know that my arms are of as good temper as thoseturned out by any craftsman in the city."

Giles Fletcher's anticipations as to the result of his guest's illnessturned out to be well founded. The fever abated, but left her prostratein strength. For a few weeks she lingered; but she seemed to have littlehold of life, and to care not whether she lived or died. So, graduallyshe faded away.

"I know you will take care of my boy as if he were your own, Bertha,"she said one day; "and you and your husband will be far betterprotectors for him than I should have been had I lived. Teach him to behonest and true. It were better, methinks, that he grew up thinking youhis father and mother, for otherwise he may grow discontented withhis lot; but this I leave with you, and you must speak or keep silentaccording as you see his disposition and mind. If he is content tosettle down to a peaceful life here, say nought to him which wouldunsettle his mind; but if Walter turn out to have an adventurousdisposition, then tell him as much as you think fit of his history, notencouraging him to hope to recover his father's lands and mine, for thatcan never be, seeing that before that time can come they would have beenenjoyed for many years by others; but that he may learn to bear himselfbravely and gently as becomes one of good blood."

A few days later Lady Alice breathed her last, and at her own requestwas buried quietly and without pomp, as if she had been a child of thebowman, a plain stone, with the name "Dame Alice Somers", marking thegrave.

The boy grew and throve until at fourteen years old there was nostronger or sturdier lad of his age within the city bounds. Giles hadcaused him to be taught to read and write, accomplishments which werecommon among the citizens, although they were until long afterwards rareamong the warlike barons. The greater part of his time, however, wasspent in sports with lads of his own age in Moorfields beyond the walls.The war with France was now raging, and, as was natural, the boys intheir games imitated the doings of their elders, and mimic battles,ofttimes growing into earnest, were fought between the lads ofthe different wards. Walter Fletcher, as he was known among hisplay-fellows, had by his strength and courage won for himself the proudposition of captain of the boys of the ward of Aldgate.

Geoffrey Ward had kept his word, and had already begun to give the ladlessons in the use of arms. When not engaged otherwise Walter would,almost every afternoon, cross London Bridge and would spend hours in thearmourer's forge. Geoffrey's business had grown, for the war had causeda great demand for arms, and he had now six men working in the forge. Assoon as the boy could handle a light tool Geoffrey allowed him to work,and although not able to wield the heavy sledge Walter was able to domuch of the finer work. Geoffrey encouraged him in this, as, in thefirst place, the use of the tools greatly strengthened the boy'smuscles, and gave him an acquaintance with arms. Moreover, Geoffrey wasstill a bachelor, and he thought that the boy, whom he as well as Gileshad come to love as a son, might, should he not take up the trade ofwar, prefer the occupation of an armourer to that of a bowmaker, inwhich case he would take him some day as his partner in the forge. Afterwork was over and the men had gone away, Geoffrey would give the ladinstructions in the use of the arms at which he had been at work, and soquick and strong was he that he rapidly acquired their use, and Geoffreyforesaw that he would one day, should his thoughts turn that way, provea mighty man-at-arms.

It was the knowledge which he acquired from Geoffrey which had much todo with Walter's position among his comrades. The skill and strengthwhich he had acquired in wielding the hammer, and by practice with thesword rendered him a formidable opponent with the sticks, whichformed the weapons in the mimic battles, and indeed not a few were thecomplaints which were brought before Giles Fletcher of bruises and hurtscaused by him.

"You are too turbulent, Walter," the bowyer said one day when ahaberdasher from the ward of Aldersgate came to complain that his son'shead had been badly cut by a blow with a club from Walter Fletcher. "Youare always getting into trouble, and are becoming the terror of otherboys. Why do you not play more quietly? The feuds between the boys ofdifferent wards are becoming a serious nuisance, and many injuries havebeen inflicted. I hear that the matter has been mentioned in the CommonCouncil, and that there is a talk of issuing an order that no boy notyet apprenticed to a trade shall be allowed to carry a club, and thatany found doing so shall be publicly whipped."

"I don't want to be turbulent," Walter said; "but if the Aldersgate boyswill defy us, what are we to do? I don't hit harder than I can help, andif Jonah Harris would leave his head unguarded I could not help hittingit."

"I tell you it won't do, Walter," Giles said. "You will be gettingyourself into sore trouble. You are growing too masterful altogether,and have none of the quiet demeanour and peaceful air which becomes anhonest citizen. In another six months you will be apprenticed, and thenI hope we shall hear no more of these doings."

"My father is talking of apprenticing me, Master Geoffrey," Walter saidthat evening. "I hope that you will, as you were good enough to promise,talk with him about apprenticing me to your craft rather than to his. Ishould never take to the making of bows, though, indeed, I like wellto use them; and Will Parker, who is teaching me says that I show rarepromise; but it would never be to my taste to stand all day sawing, andsmoothing, and polishing. One bow is to me much like another, though myfather holds that there are rare differences between them; but it is anobler craft to work on iron, and next to using arms the most pleasantthing surely is to make them. One can fancy what good blows the swordwill give and what hard knocks the armour will turn aside; but some day,Master Geoffrey, when I have served my time, I mean to follow the army.There is always work there for armourers to do, and sometimes at a pinchthey may even get their share of fighting."

Walter did not venture to say that he would prefer to be a man-at-arms,for such a sentiment would be deemed as outrageous in the ears of aquiet city craftsman as would the proposal of the son of such a mannowadays to enlist as a soldier. The armourer smiled; he knew wellenough what was in Walter's mind. It had cost Geoffrey himself a hardstruggle

to settle down to a craft, and deemed it but natural thatwith the knightly blood flowing in Walter's veins he should long todistinguish himself in the field. He said nothing of this, however, butrenewed his promise to speak to Giles Fletcher, deeming that a few yearspassed in his forge would be the best preparation which Walter couldhave for a career as a soldier.