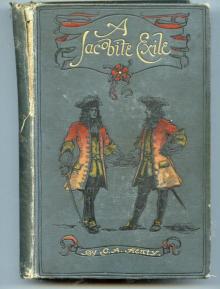

A Jacobite Exile

G. A. Henty

E-text prepared by Martin Robb

A JACOBITE EXILE:

Being the Adventures of a Young Englishmanin the Service of Charles the Twelfth of Sweden

by

G. A. Henty.

Contents

Preface. Chapter 1: A Spy in the Household. Chapter 2: Denounced. Chapter 3: A Rescue. Chapter 4: In Sweden. Chapter 5: Narva. Chapter 6: A Prisoner. Chapter 7: Exchanged. Chapter 8: The Passage of the Dwina. Chapter 9: In Warsaw. Chapter 10: In Evil Plight. Chapter 11: With Brigands. Chapter 12: Treed By Wolves. Chapter 13: A Rescued Party. Chapter 14: The Battle Of Clissow. Chapter 15: An Old Acquaintance. Chapter 16: In England Again. Chapter 17: The North Coach. Chapter 18: A Confession.

Preface.

My Dear Lads,

Had I attempted to write you an account of the whole of theadventurous career of Charles the Twelfth of Sweden, it would, initself, have filled a bulky volume, to the exclusion of all othermatter; and a youth, who fought at Narva, would have been amiddle-aged man at the death of that warlike monarch, before thewalls of Frederickshall. I have, therefore, been obliged to confinemyself to the first three years of his reign, in which he crushedthe army of Russia at Narva, and laid the then powerful republic ofPoland prostrate at his feet. In this way, only, could I obtainspace for the private adventures and doings of Charlie Carstairs,the hero of the story. The details of the wars of Charles theTwelfth were taken from the military history, written at hiscommand by his chamberlain, Adlerfeld; from a similar narrative bya Scotch gentleman in his service; and from Voltaire's history. Thelatter is responsible for the statement that the trade of Polandwas almost entirely in the hands of Scotch, French, and Jewishmerchants, the Poles themselves being sharply divided into the twocategories of nobles and peasants.

Yours sincerely,

G. A. Henty.

Chapter 1: A Spy in the Household.

On the borders of Lancashire and Westmoreland, two centuries since,stood Lynnwood, a picturesque mansion, still retaining something ofthe character of a fortified house. It was ever a matter of regretto its owner, Sir Marmaduke Carstairs, that his grandfather had somodified its construction, by levelling one side of the quadrangle,and inserting large mullion windows in that portion inhabited bythe family, that it was in no condition to stand a siege, in thetime of the Civil War.

Sir Marmaduke was, at that time, only a child, but he stillremembered how the Roundhead soldiers had lorded it there, when hisfather was away fighting with the army of the king; how they hadseated themselves at the board, and had ordered his mother about asif she had been a scullion, jeering her with cruel words as to whatwould have been the fate of her husband, if they had caught himthere, until, though but eight years old, he had smitten one of thetroopers, as he sat, with all his force. What had happened afterthat, he did not recollect, for it was not until a week after theRoundheads had ridden away that he found himself in his bed, withhis mother sitting beside him, and his head bandaged with clothsdipped in water. He always maintained that, had the house beenfortified, it could have held out until help arrived, although, inlater years, his father assured him that it was well it was not ina position to offer a defence.

"We were away down south, Marmaduke, and the Roundheads weremasters of this district, at the time. They would have battered theplace around your mother's ears, and, likely as not, have burnt itto the ground. As it was, I came back here to find it whole andsafe, except that the crop-eared scoundrels had, from purewantonness, destroyed the pictures and hacked most of the furnitureto pieces. I took no part in the later risings, seeing that theywere hopeless, and therefore preserved my property, when manyothers were ruined.

"No, Marmaduke, it is just as well that the house was notfortified. I believe in fighting, when there is some chance, even aslight one, of success, but I regard it as an act of folly, tothrow away a life when no good can come of it."

Still, Sir Marmaduke never ceased to regret that Lynnwood was notone of the houses that had been defended, to the last, against theenemies of the king. At the Restoration he went, for the first timein his life, to London, to pay his respects to Charles the Second.He was well received, and although he tired, in a very short time,of the gaieties of the court, he returned to Lynnwood with hisfeelings of loyalty to the Stuarts as strong as ever. He rejoicedheartily when the news came of the defeat of Monmouth at Sedgemoor,and was filled with rage and indignation when James weakly fled,and left his throne to be occupied by Dutch William.

From that time, he became a strong Jacobite, and emptied his glassnightly "to the king over the water." In the north the Jacobiteswere numerous, and at their gatherings treason was freely talked,while arms were prepared, and hidden away for the time when thelawful king should return to claim his own. Sir Marmaduke wasdeeply concerned in the plot of 1696, when preparations had beenmade for a great Jacobite rising throughout the country. Nothingcame of it, for the Duke of Berwick, who was to have led it, failedin getting the two parties who were concerned to come to anagreement. The Jacobites were ready to rise, directly a French armylanded. The French king, on the other hand, would not send an armyuntil the Jacobites had risen, and the matter therefore fellthrough, to Sir Marmaduke's indignation and grief. But he had nowords strong enough to express his anger and disgust when he foundthat, side by side with the general scheme for a rising, a plot hadbeen formed by Sir George Barclay, a Scottish refugee, toassassinate the king, on his return from hunting in RichmondForest.

"It is enough to drive one to become a Whig," he exclaimed. "I amready to fight Dutch William, for he occupies the place of myrightful sovereign, but I have no private feud with him, and, if Ihad, I would run any man through who ventured to propose to me aplot to assassinate him. Such scoundrels as Barclay would bringdisgrace on the best cause in the world. Had I heard as much as awhisper of it, I would have buckled on my sword, and ridden toLondon to warn the Dutchman of his danger. However, as it seemsthat Barclay had but some forty men with him, most of them foreigndesperadoes, the Dutchman must see that English gentlemen, howeverready to fight against him fairly, would have no hand in sodastardly a plot as this.

"Look you, Charlie, keep always in mind that you bear the name ofour martyred king, and be ready ever to draw your sword in thecause of the Stuarts, whether it be ten years hence, or forty, thattheir banner is hoisted again; but keep yourself free from allplots, except those that deal with fair and open warfare. Have nofaith whatever in politicians, who are ever ready to use thecountry gentry as an instrument for gaining their own ends. Dealwith your neighbours, but mistrust strangers, from whomsoever theymay say they come."

Which advice Charlie, at that time thirteen years old, gravelypromised to follow. He had naturally inherited his father'ssentiments, and believed the Jacobite cause to be a sacred one. Hehad fought and vanquished Alured Dormay, his second cousin, and twoyears his senior, for speaking of King James' son as the Pretender,and was ready, at any time, to do battle with any boy of his ownage, in the same cause. Alured's father, John Dormay, had riddenover to Lynnwood, to complain of the violence of which his son hadbeen the victim, but he obtained no redress from Sir Marmaduke.

"The boy is a chip of the old block, cousin, and he did right. Imyself struck a blow at the king's enemies, when I was but eightyears old, and got my skull well-nigh cracked for my pains. It iswell that the lads were not four years older, for then, instead oftaking to fisticuffs, their swords would have been out, and as myboy has, for the last four years, been exercised daily in the useof his weapon, it might happen that, instead of Alured coming homewith a black eye, and, as you say, a missing tooth, he might havebeen carried home with a sword thrust through his body.

"It was, to my mind, entirely the fault

of your son. I should haveblamed Charlie, had he called the king at Westminster DutchWilliam, for, although each man has a right to his own opinions, hehas no right to offend those of others--besides, at present it isas well to keep a quiet tongue as to a matter that words cannot setright. In the same way, your son had no right to offend others bycalling James Stuart the Pretender.

"Certainly, of the twelve boys who go over to learn what the Rectorof Apsley can teach them, more than half are sons of gentlemenwhose opinions are similar to my own.

"It would be much better, John Dormay, if, instead of complainingof my boy, you were to look somewhat to your own. I marked, thelast time he came over here, that he was growing loutish in hismanners, and that he bore himself with less respect to his eldersthan is seemly in a lad of that age. He needs curbing, and wouldcarry himself all the better if, like Charlie, he had an hour a dayat sword exercise. I speak for the boy's good. It is true that youyourself, being a bitter Whig, mix but little with your neighbours,who are for the most part the other way of thinking; but this maynot go on for ever, and you would, I suppose, like Alured, when hegrows up, to mix with others of his rank in the county; and itwould be well, therefore, that he should have the accomplishmentsand manners of young men of his own age."

John Dormay did not reply hastily--it was his policy to keep ongood terms with his wife's cousin, for the knight was a man of farhigher consideration, in the county, than himself. His smile,however, was not a pleasant one, as he rose and said:

"My mission has hardly terminated as I expected, Sir Marmaduke. Icame to complain, and I go away advised somewhat sharply."

"Tut, tut, man!" the knight said. "I speak only for the lad's good,and I am sure that you cannot but feel the truth of what I havesaid. What does Alured want to make enemies for? It may be that itwas only my son who openly resented his ill-timed remarks, but youmay be sure that others were equally displeased, and maybe theirresentment will last much longer than that which was quenched in afair stand-up fight. Certainly, there need be no malice between theboys. Alured's defeat may even do him good, for he cannot but feelthat it is somewhat disgraceful to be beaten by one nearly a headshorter than he."

"There is, no doubt, something in what you say, Sir Marmaduke,"John Dormay said blandly, "and I will make it my business that,should the boys meet again as antagonists, Alured shall be able togive a better account of himself."

"He is a disagreeable fellow," Sir Marmaduke said to himself, as hewatched John Dormay ride slowly away through the park, "and, if itwere not that he is husband to my cousin Celia, I would have noughtto do with him. She is my only kinswoman, and, were aught to happento Charlie, that lout, her son, would be the heir of Lynnwood. Ishould never rest quiet in my grave, were a Whig master here.

"I would much rather that he had spoken wrathfully, when Istraightly gave him my opinion of the boy, who is growing up anill-conditioned cub. It would have been more honest. I hate to seea man smile, when I know that he would fain swear. I like my cousinCelia, and I like her little daughter Ciceley, who takes after her,and not after John Dormay; but I would that the fellow lived on theother side of England. He is out of his place here, and, though mendo not speak against him in my presence, knowing that he is a sortof kinsman, I have never heard one say a good word for him.

"It is not only because he is a Whig. There are other Whig gentryin the neighbourhood, against whom I bear no ill will, and can meetat a social board in friendship. It would be hard if politics wereto stand between neighbours. It is Dormay's manner that is againsthim. If he were anyone but Celia's husband, I would say that he isa smooth-faced knave, though I altogether lack proof of my words,beyond that he has added half a dozen farms to his estate, and, ineach case, there were complaints that, although there was nothingcontrary to the law, it was by sharp practice that he obtainedpossession, lending money freely in order to build houses andfences and drains, and then, directly a pinch came, demanding thereturn of his advance.

"Such ways may pass in a London usurer, but they don't do for uscountry folk; and each farm that he has taken has closed the doorsof a dozen good houses to John Dormay. I fear that Celia has a badtime with him, though she is not one to complain. I let Charlie goover to Rockley, much oftener than I otherwise should do, for hersake and Ciceley's, though I would rather, a hundred times, thatthey should come here. Not that the visits are pleasant, when theydo come, for I can see that Celia is always in fear, lest I shouldask her questions about her life at home; which is the last thingthat I should think of doing, for no good ever comes ofinterference between man and wife, and, whatever I learned, I couldnot quarrel with John Dormay without being altogether separatedfrom Celia and the girl.

"I am heartily glad that Charlie has given Alured a soundthrashing. The boy is too modest. He only said a few words, lastevening, about the affair, and I thought that only a blow or twohad been exchanged. It was as much as I could do, not to rub myhands and chuckle, when his father told me all about it. However, Imust speak gravely to Charlie. If he takes it up, every time a Whigspeaks scornfully of the king, he will be always in hot water, and,were he a few years older, would become a marked man. We have gotto bide our time, and, except among friends, it is best to keep aquiet tongue until that time comes."

To Sir Marmaduke's disappointment, three more years went on withoutthe position changing in any way. Messengers went and came betweenFrance and the English Jacobites, but no movement was made. Thefailure of the assassination plot had strengthened William's holdon the country, for Englishmen love fair play and hate assassination,so that many who had, hitherto, been opponents of William of Orange,now ranged themselves on his side, declaring they could no longersupport a cause that used assassination as one of its weapons. Morezealous Jacobites, although they regretted the assassination plot,and were as vehement of their denunciations of its authors as werethe Whigs, remained staunch in their fidelity to "the king over thewater," maintaining stoutly that his majesty knew nothing whateverof this foul plot, and that his cause was in no way affected by themisconduct of a few men, who happened to be among its adherents.

At Lynnwood things went on as usual. Charlie continued his studies,in a somewhat desultory way, having but small affection for books;kept up his fencing lesson diligently and learned to dance;quarrelled occasionally with his cousin Alured, spent a good dealof his time on horseback, and rode over, not unfrequently, toRockley, choosing, as far as possible, the days and hours when heknew that Alured and his father were likely to be away. He wentover partly for his own pleasure, but more in compliance with hisfather's wishes.

"My cousin seldom comes over, herself," the latter said. "I know,right well, that it is from no slackness of her own, but that herhusband likes not her intimacy here. It is well, then, that youshould go over and see them, for it is only when you bring her thatI see Ciceley. I would she were your sister, lad, for she is abright little maid, and would make the old house lively."

Therefore, once a week or so, Charlie rode over early to Rockley,which was some five miles distant, and brought back Ciceley,cantering on her pony by his side, escorting her home again beforenightfall. Ciceley's mother wondered, sometimes, that her husband,who in most matters set his will in opposition to hers, neveroffered any objection to the girl's visits to Lynnwood. She thoughtthat, perhaps, he was pleased that there should be an intimacybetween some member, at least, of his family, and Sir Marmaduke's.There were so few houses at which he or his were welcome, it waspleasant to him to be able to refer to the close friendship of hisdaughter with their cousins at Lynnwood. Beyond this, Celia, whooften, as she sat alone, turned the matter over in her mind, couldsee no reason he could have for permitting the intimacy. That hewould permit it without some reason was, as her experience hadtaught her, out of the question.

Ciceley never troubled her head about the matter. Her visits toLynnwood were very pleasant to her. She was two years younger thanCharlie Carstairs; and although, when he had once brought her tothe house, he considered that his du

ties were over until the hourarrived for her return, he was sometimes ready to play with her,escort her round the garden, or climb the trees for fruit or birds'eggs for her.

Such little courtesies she never received from Alured, who was fouryears her senior, and who never interested himself in the slightestdegree in her. He was now past eighteen, and was beginning toregard himself as a man, and had, to Ciceley's satisfaction, gone afew weeks before, to London, to stay with an uncle who had a placeat court, and was said to be much in the confidence of some of theWhig lords.

Sir Marmaduke was, about this time, more convinced than ever that,ere long, the heir of the Stuarts would come over from France, withmen, arms, and money, and would rally round him the Jacobites ofEngland and Scotland. Charlie saw but little of him, for he wasfrequently absent, from early morning until late at night, ridingto visit friends in Westmoreland and Yorkshire, sometimes beingaway two or three days at a time. Of an evening, there weremeetings at Lynnwood, and at these strangers, who arrived afternightfall, were often present. Charlie was not admitted to any ofthese gatherings.

"You will know all about it in time, lad," his father said. "Youare too young to bother your head with politics, and you would losepatience in a very short time. I do myself, occasionally. Many whoare the foremost in talk, when there is no prospect of doinganything, draw back when the time approaches for action, and it issickening to listen to the timorous objections and paltry argumentsthat are brought forward. Here am I, a man of sixty, ready to risklife and fortune in the good cause, and there are many, not half myage, who speak with as much caution as if they were graybeards.Still, lad, I have no doubt that the matter will straighten itselfout, and come right in the end. It is always the most trying time,for timorous hearts, before the first shot of a battle is fired.Once the engagement commences, there is no time for fear. Thebattle has to be fought out, and the best way to safety is to win avictory. I have not the least doubt that, as soon as it is knownthat the king has landed, there will be no more shilly-shallying orhesitation. Every loyal man will mount his horse, and call out histenants, and, in a few days, England will be in a blaze from end toend."

Charlie troubled himself but little with what was going on. Hisfather had promised him that, when the time did come, he shouldride by his side, and with that promise he was content to wait,knowing that, at present, his strength would be of but littleavail, and that every week added somewhat to his weight and sinew.

One day he was in the garden with Ciceley. The weather was hot, andthe girl was sitting, in a swing, under a shady tree, occasionallystarting herself by a push with her foot on the ground, and thenswaying gently backward and forward, until the swing was again atrest. Charlie was seated on the ground, near her, pulling the earsof his favourite dog, and occasionally talking to her, when aservant came out, with a message that his father wanted to speak tohim.

"I expect I shall be back in a few minutes, Ciceley, so don't youwander away till I come. It is too hot today to be hunting for you,all over the garden, as I did when you hid yourself last week."

It was indeed but a short time until he returned.

"My father only wanted to tell me that he is just starting forBristowe's, and, as it is over twenty miles away, he may not returnuntil tomorrow."

"I don't like that man's face who brought the message to you,Charlie."

"Don't you?" the boy said carelessly. "I have not noticed him much.He has not been many months with us.

"What are you thinking of?" he asked, a minute later, seeing thathis cousin looked troubled.

"I don't know that I ought to tell you, Charlie. You know my fatherdoes not think the same way as yours about things."

"I should rather think he doesn't," Charlie laughed. "There is nosecret about that, Ciceley; but they don't quarrel over it. Lasttime your father and mother came over here, I dined with them forthe first time, and I noticed there was not a single word saidabout politics. They chatted over the crops, and the chances of awar in Europe, and of the quarrel between Holstein and Denmark, andwhether the young king of Sweden would aid the duke, who seems tobe threatened by Saxony as well as by Denmark. I did not knowanything about it, and thought it was rather stupid; but my fatherand yours both seemed of one mind, and were as good friends as ifthey were in equal agreement on all other points. But what has thatto do with Nicholson, for that is the man's name who came out justnow?"

"It does not seem to have much to do with it," she said doubtfully,"and yet, perhaps it does. You know my mother is not quite of thesame opinion as my father, although she never says so to him; but,when we are alone together, sometimes she shakes her head and saysshe fears that trouble is coming, and it makes her very unhappy.One day I was in the garden, and they were talking loudly in thedining room--at least, he was talking loudly. Well, he said--But Idon't know whether I ought to tell you, Charlie."

"Certainly you ought not, Ciceley. If you heard what you were notmeant to hear, you ought never to say a word about it to anyone."

"But it concerns you and Sir Marmaduke."

"I cannot help that," he said stoutly. "People often say things ofeach other, in private, especially if they are out of temper, thatthey don't quite mean, and it would make terrible mischief if suchthings were repeated. Whatever your father said, I do not want tohear it, and it would be very wrong of you to repeat it."

"I am not going to repeat it, Charlie. I only want to say that I donot think my father and yours are very friendly together, which isnatural, when my father is all for King William, and your fatherfor King James. He makes no secret of that, you know."

Charlie nodded.

"That is right enough, Ciceley, but still, I don't understand inthe least what it has to do with the servant."

"It has to do with it," she said pettishly, starting the swingafresh, and then relapsing into silence until it again came to astandstill.

"I think you ought to know," she said suddenly. "You see, Charlie,Sir Marmaduke is very kind to me, and I love him dearly, and so Ido you, and I think you ought to know, although it may be nothingat all."

"Well, fire away then, Ciceley. There is one thing you may be quitesure of, whatever you tell me, it is like telling a brother, and Ishall never repeat it to anyone."

"Well, it is this. That man comes over sometimes to see my father.I have seen him pass my window, three or four times, and go in bythe garden door into father's study. I did not know who he was, butit did seem funny his entering by that door, as if he did not wantto be seen by anyone in the house. I did not think anything moreabout it, till I saw him just now, then I knew him directly. If Ihad seen him before, I should have told you at once, but I don'tthink I have."

"I daresay not, Ciceley. He does not wait at table, but is underthe steward, and helps clean the silver. He waits when we haveseveral friends to dinner. At other times he does not often comeinto the room.

"What you tell me is certainly curious. What can he have to say toyour father?"

"I don't know, Charlie. I don't know anything about it. I do thinkyou ought to know."

"Yes, I think it is a good thing that I should know," Charlieagreed thoughtfully. "I daresay it is all right, but, at any rate,I am glad you told me."

"You won't tell your father?" she asked eagerly. "Because, if youwere to speak of it--"

"I shall not tell him. You need not be afraid that what you havetold me will come out. It is curious, and that is all, and I willlook after the fellow a bit. Don't think anything more about it. Itis just the sort of thing it is well to know, but I expect there isno harm in it, one way or the other. Of course, he must have knownyour father before he came to us, and may have business of somesort with him. He may have a brother, or some other relation, whowants to take one of your father's farms. Indeed, there are ahundred things he might want to see him about. But still, I am gladyou have told me."

In his own mind, Charlie thought much more seriously of it than hepretended. He knew that, at present, his father was engaged heartand soul i

n a projected Jacobite rising. He knew that John Dormaywas a bitter Whig. He believed that he had a grudge against hisfather, and the general opinion of him was that he was whollyunscrupulous.

That he should, then, be in secret communication with a servant atLynnwood, struck him as a very serious matter, indeed. Charlie wasnot yet sixteen, but his close companionship with his father hadrendered him older than most lads of his age. He was as warm aJacobite as his father, but the manner in which William, with hisDutch troops, had crushed the great Jacobite rebellion in Ireland,seemed to him a lesson that the prospects of success, in England,were much less certain than his father believed them to be.

John Dormay, as an adherent of William, would be interested inthwarting the proposed movement, with the satisfaction of, at thesame time, bringing Sir Marmaduke into disgrace. Charlie couldhardly believe that his cousin would be guilty of setting a spy towatch his father, but it was certainly possible, and as he thoughtthe matter over, as he rode back after escorting Ciceley to herhome, he resolved to keep a sharp watch over the doings of this manNicholson.

"It would never do to tell my father what Ciceley said. He wouldbundle the fellow out, neck and crop, and perhaps break some of hisbones, and then it would be traced to her. She has not a happyhome, as it is, and it would be far worse if her father knew thatit was she who had put us on our guard. I must find out somethingmyself, and then we can turn him out, without there being the leastsuspicion that Ciceley is mixed up in it."

The next evening several Jacobite gentlemen rode in, and, as usual,had a long talk with Sir Marmaduke after supper.

"If this fellow is a spy," Charlie said to himself, "he will bewanting to hear what is said, and to do so he must either hidehimself in the room, or listen at the door, or at one of thewindows. It is not likely that he will get into the room, for to dothat he must have hidden himself before supper began. I don't thinkhe would dare to listen at the door, for anyone passing through thehall would catch him at it. It must be at one of the windows."

The room was at an angle of the house. Three windows looked out onto the lawn in front; that at the side into a large shrubbery,where the bushes grew up close to it; and Charlie decided thathere, if anywhere, the man would take up his post. As soon, then,as he knew that the servants were clearing away the supper, he tooka heavy cudgel and went out. He walked straight away from thehouse, and then, when he knew that his figure could no longer beseen in the twilight, he made a circuit, and, entering theshrubbery, crept along close to the wall of the Muse, until withintwo or three yards of the window. Having made sure that at present,at any rate, no one was near, he moved out a step or two to look atthe window.

His suspicions were at once confirmed. The inside curtains weredrawn, but the casement was open two or three inches. Charlie againtook up his post, behind a bush, and waited.

In five minutes he heard a twig snap, and then a figure came along,noiselessly, and placed itself at the window. Charlie gave him buta moment to listen, then he sprang forward, and, with his wholestrength, brought his cudgel down upon the man's head. He fell likea stone. Charlie threw open the window, and, as he did so, thecurtain was torn back by his father, the sound of the blow and thefall having reached the ears of those within.

Sir Marmaduke had drawn his sword, and was about to leap throughthe window, when Charlie exclaimed:

"It is I, father. I have caught a fellow listening at the window,and have just knocked him down."

"Well done, my boy!

"Bring lights, please, gentlemen. Let us see what villain we havegot here."

But, as he spoke, Charlie's head suddenly disappeared, and a sharpexclamation broke from him, as he felt his ankles grasped and hisfeet pulled from under him. He came down with such a crash that,for a moment, he was unable to rise. He heard a rustling in thebushes, and then his father leapt down beside him.

"Where are you, my boy? Has the scoundrel hurt you?"

"He has given me a shake," Charlie said as he sat up; "and, what isworse, I am afraid he has got away."

"Follow me, gentlemen, and scatter through the gardens," SirMarmaduke roared. "The villain has escaped!"

For a few minutes, there was a hot pursuit through the shrubberyand gardens, but nothing was discovered. Charlie had been so shakenthat he was unable to join the pursuit, but, having got on to hisfeet, remained leaning against the wall until his father came back.

"He has got away, Charlie. Have you any idea who he was?"

"It was Nicholson, father. At least, I am almost certain that itwas him. It was too dark to see his face. I could see the outlineof his head against the window, and he had on a cap with a cock'sfeather which I had noticed the man wore."

"But how came you here, Charlie?"

"I will tell you that afterwards, father. Don't ask me now."

For, at this moment, some of the others were coming up. Several ofthem had torches, and, as they approached, Sir Marmaduke sawsomething lying on the ground under the window. He picked it up.

"Here is the fellow's cap," he said. "You must have hit him ashrewd blow, Charlie, for here is a clean cut through the cloth,and a patch of fresh blood on the white lining. How did he get youdown, lad?"

"He fell so suddenly, when I hit him, that I thought I had eitherkilled or stunned him; but of course I had not, for it was but amoment after, when I was speaking to you, that I felt my anklesseized, and I went down with a crash. I heard him make off throughthe bushes; but I was, for the moment, almost dazed, and could donothing to stop him."

"Was the window open when he came?"

"Yes, sir, two or three inches."

"Then it was evidently a planned thing.

"Well, gentlemen, we may as well go indoors. The fellow is well outof our reach now, and we may be pretty sure he will never againshow his face here. Fortunately he heard nothing, for the servingmen had but just left the room, and we had not yet begun to talk."

"That is true enough, Sir Marmaduke," one of the others said. "Thequestion is: how long has this been going on?"

Sir Marmaduke looked at Charlie.

"I know nothing about it, sir. Till now, I have not had theslightest suspicion of this man. It occurred to me, this afternoon,that it might be possible for anyone to hear what was said insidethe room, by listening at the windows; and that this shrubberywould form a very good shelter for an eavesdropper. So I thought,this evening I would take up my place here, to assure myself thatthere was no traitor in the household. I had been here but fiveminutes when the fellow stole quietly up, and placed his ear at theopening of the casement, and you may be sure that I gave him notime to listen to what was being said."

"Well, we had better go in," Sir Marmaduke said. "There is no fearof our being overheard this evening.

"Charlie, do you take old Banks aside, and tell him what hashappened, and then go with him to the room where that fellow slept,and make a thorough search of any clothes he may have left behind,and of the room itself. Should you find any papers or documents,you will, of course, bring them down to me."

But the closest search, by Charlie and the old butler, produced noresults. Not a scrap of paper of any kind was found, and Banks saidthat he knew the man could neither read nor write.

The party below soon broke up, considerable uneasiness being felt,by all, at the incident of the evening. When the last of them hadleft, Charlie was sent for.

"Now, then, Charlie, let me hear how all this came about. I knowthat all you said about what took place at the window is perfectlytrue; but, even had you not said so, I should have felt there wassomething else. What was it brought you to that window? Your storywas straight-forward enough, but it was certainly singular yourhappening to be there, and I fancy some of our friends thought thatyou had gone round to listen, yourself. One hinted as much; but Isaid that was absurd, for you were completely in my confidence, andthat, whatever peril and danger there might be in the enterprise,you would share them with me."

"It is not pleasant that they should have t

hought so, father, butthat is better than that the truth should be known. This is how ithappened;" and he repeated what Ciceley had told him in the garden.

"So the worthy Master John Dormay has set a spy upon me," SirMarmaduke said, bitterly. "I knew the man was a knave--that ispublic property--but I did not think that he was capable of this.Well, I am glad that, at any rate, no suspicion can fall uponCiceley in the matter; but it is serious, lad, very serious. We donot know how long this fellow has been prying and listening, or howmuch he may have learnt. I don't think it can be much. We talked itover, and my friends all agreed with me that they do not rememberthose curtains having been drawn before. To begin with, theevenings are shortening fast, and, at our meeting last week, wefinished our supper by daylight; and, had the curtains been drawn,it would have been noticed, for we had need of light before wefinished. Two of the gentlemen, who were sitting facing the window,declared that they remembered distinctly that it was open. Mr.Jervoise says that he thought to himself that, if it was his place,he would have the trees cut away there, for they shut out thelight.

"Therefore, although it is uncomfortable to think that there hasbeen a spy in the house, for some months, we have every reason tohope that our councils have not been overheard. Were it otherwise,I should lose no time in making for the coast, and taking ship toFrance, to wait quietly there until the king comes over."

"You have no documents, father, that the man could have found?"

"None, Charlie. We have doubtless made lists of those who could berelied upon, and of the number of men they could bring with them,but these have always been burned before we separated. Such lettersas I have had from France, I have always destroyed as soon as Ihave read them. Perilous stuff of that sort should never be leftabout. No; they may ransack the place from top to bottom, andnothing will be found that could not be read aloud, without harm,in the marketplace of Lancaster.

"So now, to bed, Charlie. It is long past your usual hour."