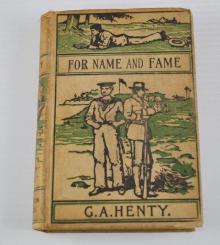

For Name and Fame; Or, Through Afghan Passes

G. A. Henty

FOR NAME AND FAME

Or Through Afghan Passes

by

G. A. HENTY.

Contents

Preface. Chapter 1: The Lost Child. Chapter 2: The Foundling. Chapter 3: Life On A Smack. Chapter 4: Run Down. Chapter 5: The Castaways. Chapter 6: The Attack On The Village. Chapter 7: The Fight With The Prahus. Chapter 8: The Torpedo. Chapter 9: The Advance Into Afghanistan. Chapter 10: The Peiwar-Khotal. Chapter 11: A Prisoner. Chapter 12: The Advance Up The Khyber. Chapter 13: The Massacre At Cabul. Chapter 14: The Advance Upon Cabul. Chapter 15: The Fighting Round Cabul. Chapter 16: The Fight In The Pass. Chapter 17: At Candahar. Chapter 18: On The Helmund. Chapter 19: The Battle Of Maiwand. Chapter 20: Candahar. Chapter 21: The Battle Of Candahar. Chapter 22: At Home At Last.

Illustrations

Sam Dickson finds little Willie Gale. Will and Hans in Search of a Shelter. Captain Herbert saved. William Gale in the hands of the Afghans. One of the Gunpowder Magazines had Exploded. Letters from the General. Will saves Colonel Ripon. Gundi carried by the Bayonet.

Preface.

In following the hero of this story through the last Afghan war,you will be improving your acquaintance with a country which is ofsupreme importance to the British Empire and, at the same time, beable to trace the operations by which Lord Roberts made his greatreputation as a general, and a leader of men. Afghanistan stands asa line between the two great empires of England and Russia; and islikely, sooner or later, to become the scene of a tremendousstruggle between these nations. Happily, at the present time theAfghans are on our side. It is true that we have warred with, andbeaten them; but our retirement, after victory, has at least shownthem that we have no desire to take their country while, on theother hand, they know that for those races upon whom Russia hasonce laid her hand there is no escape.

In these pages you will see the strength and the weakness of thesewild people of the mountains; their strength lying in theirpersonal bravery, their determination to preserve their freedom atall costs, and the nature of their country. Their weakness consistsin their want of organization, their tribal jealousies, and theirimpatience of regular habits and of the restraint necessary torender them good soldiers. But, when led and organized by Englishofficers, there are no better soldiers in the world; as is provedby the splendid services which have been rendered by the frontierforce, which is composed almost entirely of Afghan tribesmen.

Their history shows that defeat has little moral effect upon them.Crushed one day, they will rise again the next; scattered--it wouldseem hopelessly--they are ready to reassemble, and renew theconflict, at the first summons of their chiefs. Guided by Britishadvice, led by British officers and, it may be, paid by Britishgold, Afghanistan is likely to prove an invaluable ally to us, whenthe day comes that Russia believes herself strong enough to moveforward towards the goal of all her hopes and efforts, for the lastfifty years--the conquest of India.

G. A. Henty.

Chapter 1: The Lost Child.

"My poor pets!" a lady exclaimed, sorrowfully; "it is too bad. Theyall knew me so well; and ran to meet me, when they saw me coming;and seemed really pleased to see me, even when I had no food togive them."

"Which was not often, my dear," Captain Ripon--her husband--said."However it is, as you say, too bad; and I will bring the fellow tojustice, if I can. There are twelve prize fowls--worth a couple ofguineas apiece, not to mention the fact of their being pets ofyours--stolen, probably by tramps; who will eat them, and for whomthe commonest barn-door chickens would have done as well. There aremarks of blood in two or three places, so they have evidently beenkilled for food. The house was locked up last night, all right; foryou see they got in by breaking in a panel of the door.

"Robson, run down to the village, at once, and tell the policemanto come up here; and ask if any gypsies, or tramps, have been seenin the neighborhood."

The village lay at the gate of Captain Ripon's park, and thegardener soon returned with the policeman.

"I've heard say there are some gypsies camped on Netherwood Common,four miles away," that functionary said, in answer to CaptainRipon.

"Put the gray mare in the dog cart, Sam. We will drive over atonce. They will hardly expect us so soon. We will pick up anotherpoliceman, at Netherwood. They may show fight, if we are not instrength."

Five minutes later, Captain Ripon was traveling along the road atthe rate of twelve miles an hour; with Sam by his side, and thepoliceman sitting behind. At Netherwood they took up anotherpoliceman and, a few minutes later, drove up to the gypsyencampment.

There was a slight stir when they were seen approaching; and thenthe gypsies went on with their usual work, the women weavingbaskets from osiers, the men cutting up gorse into skewers. Therewere four low tents, and a wagon stood near; a bony horse grazingon the common.

"Now," Captain Ripon said, "I am a magistrate, and I daresay youknow what I have come for. My fowl house has been broken open, andsome valuable fowls stolen.

"Now, policeman, look about, and see if you can find any traces ofthem."

The gypsies rose to their feet, with angry gestures.

"Why do you come to us?" one of the men said. "When a fowl isstolen you always suspect us, as if there were no other thieves inthe world."

"There are plenty of other thieves, my friend; and we shall notinterfere with you, if we find nothing suspicious."

"There have been some fowls plucked, here," one of the policemensaid. "Here is a little feather--" and he showed one, of only halfan inch in length "--and there is another, on that woman's hair.They have cleaned them up nicely enough, but it ain't easy to pickup every feather. I'll be bound we find a fowl, in the pot."

Two of the gypsies leaped forward, stick in hand; but the oldestman present said a word or two to them, in their own dialect.

"You may look in the pot," he said, turning to Captain Ripon, "andmaybe you will find a fowl there, with other things. We bought 'emat the market at Hunston, yesterday."

The policeman lifted the lid off the great pot, which was hangingover the fire, and stirred up the contents with a stick.

"There's rabbits here--two or three of them, I should say--and afowl, perhaps two, but they are cut up."

"I cannot swear to that," Captain Ripon said, examining theportions of fowl, "though the plumpness of the breasts, and thesize, show that they are not ordinary fowls."

He looked round again at the tents.

"But I can pretty well swear to this," he said, as he stooped andpicked up a feather which lay, half concealed, between the edge ofone of the tents and the grass. "This is a breast feather of aSpangled Dorking. These are not birds which would be sold foreating in Hunston market, and it will be for these men to showwhere they got it from."

A smothered oath broke from one or two of the men. The elder signedto them to be quiet.

"That's not proof," he said, insolently. "You can't convict fivemen, because the feather of a fowl which you cannot swear to isfound in their camp."

"No," Captain Ripon said, quietly. "I do not want to convict anyonebut the thief; but the proof is sufficient for taking you incustody, and we shall find out which was the guilty man,afterwards.

"Now, lads, it will be worse for you, if you make trouble.

"Constables, take them up to Mr. Bailey. He lives half a mile away.Fortunately, we have means of proving which is the fellowconcerned.

"Now, Sam, you and I will go up with the Netherwood constable toMr. Bailey.

"And do you," he said, to the other policeman, "keep a sharp watchover these women. You say you can find n

othing in the tents; but itis likely the other fowls are hid, not far off, and I will put allthe boys of the village to search, when I come back."

The gypsies, with sullen faces, accompanied Captain Ripon and thepoliceman to the magistrate's.

"Is that feather the only proof you have, Ripon?" Mr. Bailey asked,when he had given his evidence. "I do not think that it will beenough to convict, if unsupported; besides, you cannot bring ithome to any one of them. But it is sufficient for me to have themlocked up for twenty-four hours and, in the meantime, you may findthe other fowls."

"But I have means of identification," Captain Ripon said. "There isa footmark in some earth, at the fowl house door. It is made by aboot which has got hobnails and a horseshoe heel, and a piece ofthat heel has been broken off.

"Now, which of these men has got such a boot on? Whichever has, heis the man."

There was a sudden movement among the accused.

"It's of no use," one of them said, when the policeman approachedto examine their boots. "I'm the man, I'll admit it. I can't getover the boot," and he held up his right foot.

"That is the boot, sir," the constable exclaimed. "I can swear thatit will fit the impression, exactly."

"Very well," the magistrate said. "Constable, take that man to thelockup; and bring him before the bench, tomorrow, for finalcommittal for trial. There is no evidence against the other four.They can go."

With surly, threatening faces the men left the room; while theconstable placed handcuffs on the prisoner.

"Constable," Mr. Bailey said, "you had better not put this man inthe village lockup. The place is of no great strength, and hiscomrades would as likely as not get him out, tonight. Put him in mydog cart. My groom shall drive you over to Hunston."

Captain Ripon returned with his groom to Netherwood, and set allthe children searching the gorse, copses, and hedges near thecommon, by the promise of ten shillings reward, if they found themissing fowls. Half an hour later, the gypsies struck their tents,loaded the van, and went off.

Late that afternoon, the ten missing fowls were discovered in asmall copse by the wayside, half a mile from the common, on theroad to Captain Ripon's park.

"I cannot bring your fowls back to life, Emma," that gentlemansaid, when he returned home, "but I have got the thief. It was oneof the gypsies on Netherwood Common. We found two of the fowls intheir pot. No doubt they thought that they would have plenty oftime to get their dinner before anyone came, even if suspicion fellon them; and they have hidden the rest away somewhere, but I expectthat we shall find them.

"They had burnt all the feathers, as they thought; but I found abreast feather of a Spangled Dorking, and that was enough for me togive them in custody. Then, when it came to the question of boots,the thief found it no good to deny it, any longer."

That evening, Captain Ripen was told that a woman wished to speakto him and, on going out into the hall, he saw a gypsy of somethirty years of age.

"I have come, sir, to beg you not to appear against my husband."

"But, my good woman, I see no reason why I should not do so. If hehad only stolen a couple of common fowls, for a sick wife or child,I might have been inclined to overlook it--for I am not fond ofsending men to prison--but to steal a dozen valuable fowls, for thepot, is a little too much. Besides, the matter has gone too far,now, for me to retract, even if I wished to--which I certainly donot."

"He is a good husband, sir."

"He may be," Captain Ripon said, "though that black eye you havegot does not speak in his favor But that has nothing to do with it.Matters must take their course."

The woman changed her tone.

"I have asked you fairly, sir; and it will be better for you if youdon't prosecute Reuben."

"Oh, nonsense, my good woman! Don't let me have any threats, or itwill be worse for you."

"I tell you," the woman exclaimed, fiercely, "it will be the worsefor you, if you appear against my Reuben."

"There, go out," Captain Ripon said, opening the front door of thehall. "As if I cared for your ridiculous threats! Your husband willget what he deserves--five years, if I am not mistaken."

"You will repent this," the gypsy said, as she passed out.

Captain Ripon closed the door after her, without a word.

"Well, who was it?" his wife inquired, when he returned to thedrawing room.

"An insolent gypsy woman, wife of the man who stole the fowls. Shehad the impudence to threaten me, if I appeared against him."

"Oh, Robert!" the young wife exclaimed, apprehensively, "what couldshe do? Perhaps you had better not appear."

"Nonsense, my dear!" her husband laughed. "Not appear, because animpudent gypsy woman has threatened me? A nice magistrate I shouldbe! Why, half the fellows who are committed swear that they willpay off the magistrate, some day; but nothing ever comes of it.Here, we have been married six months, and you are wanting me toneglect my duty; especially when it is your pet fowls which havebeen stolen.

"Why, at the worst, my dear," he went on, seeing that his wifestill looked pale, "they could burn down a tick or two, on a windynight in winter and, to satisfy you, I will have an extra sharplookout kept in that direction, and have a watchdog chained up nearthem.

"Come, my love, it is not worth giving a second thought about; andI shall not tell you about my work on the bench, if you are goingto take matters to heart like this."

The winter came and went, and the ricks were untouched, and CaptainRipon forgot all about the gypsy's threats. At the assizes aprevious conviction was proved against her husband, and he got fiveyears penal servitude and, after the trial was over, the matterpassed out of the minds of both husband and wife.

They had, indeed, other matters to think about for, soon afterChristmas, a baby boy was born, and monopolized the greater portionof his mother's thoughts. When, in due time, he was taken out forwalks, the old women of the village--perhaps with an eye topresents from the Park--were unanimous in declaring that he was thefinest boy ever seen, and the image both of his father and mother.

He certainly was a fine baby; and his mother lamented sorely overthe fact that he had a dark blood mark, about the size of athree-penny piece, upon his shoulder. Her husband, however,consoled her by pointing out that--as it was a boy--the mark didnot matter in the slightest; whereas--had it been a girl--the markwould have been a disfigurement, when she attained to the dignifiedage at which low dresses are worn.

"Yes, of course, that would have been dreadful, Robert. Still, youknow, it is a pity."

"I really cannot see that it is even a pity, little woman; and itwould have made no great difference if he had been spotted allover, like a leopard, so that his face and arms were free. The onlydrawback would have been he would have got some nickname or other,such as 'the Leopard,' or 'Spotty,' or something of that sort, whenhe went to bathe with his school fellows. But this little spot doesnot matter, in the slightest.

"Some day or other Tom will laugh, when I tell him what a fuss youmade over it."

Mrs. Ripon was silenced but, although she said nothing more aboutit, she was grieved in her heart at this little blemish on her boy;and lamented that it would spoil his appearance, when he began torun about in little short frocks; and she determined, at once, thathe should wear long curls, until he got into jackets.

Summer, autumn, and winter came and passed. In the spring, TomRipon was toddling about; but he had not yet begun to talk,although his mother declared that certain incoherent sounds, whichhe made, were quite plain and distinct words; but her husband,while willing to allow that they might be perfectly intelligible toher, insisted that--to the male ear--they in no way resembledwords.

"But he ought to begin to talk, Robert," his wife urged. "He issixteen months old, now, and can run about quite well. He reallyought to begin to talk."

"He will talk, before long," her husband said, carelessly. "Manychildren do not talk till they are eighteen months old, some nottill they are two years. Besides, you say he does begin, alrea

dy."

"Yes, Robert, but not quite plainly."

"No, indeed, not plainly at all," her husband laughed. "Don'ttrouble, my dear, he will talk soon enough; and if he only talks asloud as he roars, sometimes, you will regret the hurry you havebeen in about it."

"Oh, Robert, how can you talk so? I am sure he does not cry morethan other children. Nurse says he is the best child she everknew."

"Of course she does, my dear; nurses always do. But I don't say heroars more than other children. I only say he roars, and thatloudly; so you need not be afraid of there being anything thematter with his tongue, or his lungs.

"What fidgets you young mothers are, to be sure!"

"And what heartless things you young fathers are, to be sure!" hiswife retorted, laughing. "Men don't deserve to have children. Theydo not appreciate them, one bit."

"We appreciate them, in our way, little woman; but it is not afussy way. We are content with them as they are, and are not in anyhurry for them to run, or to walk, or to cut their first teeth. Tomis a fine little chap, and I am very fond of him, in hisway--principally, perhaps, because he is your Tom--but I cannot seethat he is a prodigy."

"He is a prodigy," Mrs. Ripon said, with a little toss of her head,"and I shall go up to the nursery, to admire him."

So saying, she walked off with dignity; and Captain Ripon went outto look at his horses, and thought to himself what a wonderfuldispensation of providence it was, that mothers were so fond oftheir babies.

"I don't know what the poor little beggars would do," he muttered,"if they had only their fathers to look after them; but I supposewe should take to it, just as the old goose in the yard has takento that brood of chickens, whose mother was carried off by the fox.

"By the way, I must order some wire netting. I forgot to write forit, yesterday."

Another two months. It was June, and now even Captain Ripon allowedthat Tom could say "Pa," and "Ma," with tolerable distinctness; butas yet he had got no farther. He could now run about sturdily and,as the season was warm and bright, and Mrs. Ripon believed in freshair, the child spent a considerable portion of his time in thegarden.

One day his mother was out with him, and he had been running aboutfor some time. Mrs. Ripon was picking flowers, for she had a dinnerparty that evening, and she enjoyed getting her flowers, andarranging her vases, herself. Presently she looked round, but Tomwas missing. There were many clumps of ornamental shrubs on thelawn, and Mrs. Ripon thought nothing of his disappearance.

"Tom," she called, "come to mamma, she wants you," and went on withher work.

A minute or two passed.

"Where is that little pickle?" she said. "Hiding, I suppose," andshe went off in search.

Nowhere was Tom to be seen. She called loudly, and searched in thebushes.

"He must have gone up to the house.

"Oh, here comes nurse. Nurse, have you seen Master Tom? He has justrun away," she called.

"No, ma'am, I have seen nothing of him."

"He must be about the garden then, somewhere. Look about, nurse.Where can the child have hidden itself?"

Nurse and mother ran about, calling loudly the name of the missingchild. Five minutes later Mrs. Ripon ran into the study, where herhusband was going through his farm accounts.

"Oh, Robert," she said, "I can't find Tom!" and she burst intotears.

"Not find Tom?" her husband said, rising in surprise. "Why, howlong have you missed him?"

"He was out in the garden with me. I was picking flowers for thedinner table and, when I looked round, he was gone. Nurse and Ihave been looking everywhere, and calling, but we cannot find him."

"Oh, he is all right," Captain Ripon said, cheerfully. "Do notalarm yourself, little woman. He must have wandered into theshrubbery. We shall hear him howling, directly. But I will come andlook for him."

No better success attended Captain Ripon's search than that whichhis wife had met with. He looked anxious, now. The gardeners andservants were called, and soon every place in the garden wasransacked.

"He must have got through the gate, somehow, into the park,"Captain Ripon said, hurrying in that direction. "He certainly isnot in the garden, or in any of the hothouses."

Some of the men had already gone in that direction. PresentlyCaptain Ripon met one, running back.

"I have been down to the gate, sir, and can see nothing of MasterTom; but in the middle of the drive, just by the clump of laurelsby the gate, this boot was lying--just as if it had been put thereon purpose, to be seen."

"Nonsense!" Captain Ripon said. "What can that have to do with it?"

Nevertheless he took the boot, and looked at it. It was aroughly-made, heavy boot, such as would be worn by a laboring man.He was about to throw it carelessly aside, and to proceed on hissearch, when he happened to turn it over. Then he started, as ifstruck.

"Good Heaven!" he exclaimed, "it is the gypsy's."

Yes, he remembered it now. The man had pleaded not guilty, whenbrought up at the assizes, and the boot had been produced asevidence. He remembered it particularly because, after the man wassentenced, his wife had provoked a smile by asking that the bootsmight be given up to her; in exchange for a better pair for herhusband to put on, when discharged from prison.

Yes, it was clear. The gypsy woman had kept her word, and had takenher revenge. She had stolen the child, and had placed the bootwhere it would attract attention, in order that the parents mightknow the hand that struck them.

Instantly Captain Ripon ran to the stable, ordered the groom tomount at once, and scour every road and lane; while he himself rodeoff to Hunston to give notice to the police, and offer a largereward for the child's recovery. He charged the man who had broughtthe boot to carry it away, and put it in a place of safety till itwas required; and on no account to mention to a soul where he putit.

Before riding off he ran in to his wife, who was half wild withgrief, to tell her that he was going to search outside the park;and that she must keep up her spirits for, no doubt, Tom would turnup all right, in no time.

He admitted to himself, however, as he galloped away, that he wasnot altogether sure that Tom would be so speedily recovered. Thewoman would never have dared to place the boot on the road, and sogive a clue against herself, unless she felt very confident thatshe could get away, or conceal herself.

"She has probably some hiding place, close by the park," he said tohimself, "where she will lie hid till night, and will then makeacross country."

He paused at the village, and set the whole population at work, bytelling them that his child was missing--and had, he believed, beencarried off by a gypsy woman--and that he would give fifty poundsto anyone who would find him. She could not be far off, as it wasonly about half an hour since the child had been missed.

Then he galloped to Hunston, set the police at work and, going to aprinter, told him instantly to set up and strike off placards,offering five hundred pounds reward for the recovery of the child.This was to be done in an hour or two, and then taken to the policestation for distribution throughout the country round. Having nowdone all in his power, Captain Ripon rode back as rapidly as he hadcome, in hopes that the child might already have been found.

No news had, however, been obtained of him, nor had anyone seen anystrange woman in the neighborhood.

On reaching the house, he found his wife prostrated with grief and,in answer to her questions, he thought it better to tell her aboutthe discovery of the boot.

"We may be some little time, before we find the boy," he said; "butwe shall find him, sooner or later. I have got placards outalready, offering five hundred pounds reward; and this evening Iwill send advertisements to all the papers in this and theneighboring counties.

"Do not fret, darling. The woman has done it out of spite, nodoubt; but she will not risk putting her neck in a noose, byharming the child. It is a terrible grief, but it will only be fora time. We are sure to find him before long."

Later in the evening, when Mrs. Ripon had

somewhat recovered hercomposure, she said to her husband:

"How strange are God's ways, Robert. How wicked and wrong in us togrumble! I was foolish enough to fret over that mark on thedarling's neck, and now the thought of it is my greatest comfort.If it should be God's will that months or years should pass over,before we find him, there is a sign by which we shall always knowhim. No other child can be palmed off upon us, as our own. When wefind Tom we shall know him, however changed he may be!"

"Yes, dear," her husband said, "God is very good, and this trialmay be sent us for the best. As you say, we can take comfort, now,from what we were disposed to think, at the time, a little cross.After that, dear, we may surely trust in God. That mark was placedthere that we might know our boy again and, were it not decreedthat we should again see him, that mark would have been useless."

The thought, for a time, greatly cheered Mrs. Ripon but, gradually,the hope that she should ever see her boy again faded away; andCaptain Ripon became much alarmed at the manifest change in herhealth.

In spite of all Captain Ripon could do, no news was obtained of thegypsy, or Tom. For weeks he rode about the country, askingquestions in every village; or hurried away to distant parts ofEngland, where the police thought they had a clue.

It was all in vain. Every gypsy encampment in the kingdom wassearched, but without avail; and even the police, sharp eyed asthey are, could not guess that the decent-looking Irishwoman,speaking--when she did speak, which was seldom, for she was ataciturn woman--with a strong brogue, working in a laundry in asmall street in the Potteries, Notting Hill, was the gypsy theywere looking for; or that the little boy, whose father she said wasat sea, was the child for whose discovery a thousand pounds wascontinually advertised.