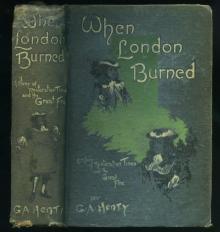

When London Burned : a Story of Restoration Times and the Great Fire

G. A. Henty

Produced by Charles Aldarondo, Tiffany Vergon, S.R. Ellison,and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team.

WHEN LONDON BURNED

BY G. A. HENTY

PREFACE

We are accustomed to regard the Reign of Charles II. as one of themost inglorious periods of English History; but this was far frombeing the case. It is true that the extravagance and profligacy ofthe Court were carried to a point unknown before or since,forming,--by the indignation they excited among the people atlarge,--the main cause of the overthrow of the House of Stuart. But,on the other hand, the nation made extraordinary advances in commerceand wealth, while the valour of our sailors was as conspicuous underthe Dukes of York and Albemarle, Prince Rupert and the Earl ofSandwich, as it had been under Blake himself, and their victoriesresulted in transferring the commercial as well as the navalsupremacy of Holland to this country. In spite of the cruel blowsinflicted on the well-being of the country, alike by the extravaganceof the Court, the badness of the Government, the Great Plague, andthe destruction of London by fire, an extraordinary extension of ourtrade occurred during the reign of Charles II. Such a period,therefore, although its brilliancy was marred by dark shadows, cannotbe considered as an inglorious epoch. It was ennobled by the braveryof our sailors, by the fearlessness with which the coalition ofFrance with Holland was faced, and by the spirit of enterprise withwhich our merchants and traders seized the opportunity, and, in spiteof national misfortunes, raised England in the course of a few yearsto the rank of the greatest commercial power in the world.

G. A. HENTY.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

I. FATHERLESS

II. A CHANGE FOR THE BETTER

III. A THIEF SOMEWHERE

IV. CAPTURED

V. KIDNAPPED

VI. A NARROW ESCAPE

VII. SAVED FROM A VILLAIN

VIII. THE CAPTAIN'S YARN

IX. THE FIRE IN THE SAVOY

X. HOW JOHN WILKES FOUGHT THE DUTCH

XI. PRINCE RUPERT

XII. NEW FRIENDS

XIII. THE BATTLE OF LOWESTOFT

XIV. HONOURABLE SCARS

XV. THE PLAGUE

XVI. FATHER AND SON

XVII. SMITTEN DOWN

XVIII. A STROKE OF GOOD FORTUNE

XIX. TAKING POSSESSION

XX. THE FIGHT OFF DUNKIRK

XXI. LONDON IN FLAMES

XXII. AFTER THE FIRE

ILLUSTRATIONS

"WITH GREAT RAPIDITY THE FLAMES SPREAD FROM HOUSE TO HOUSE"

"DON'T CRY, LAD; YOU WILL GET ON BETTER WITHOUT ME"

"THIS IS MY PRINCE OF SCRIVENERS, MARY"

"ROBERT ASHFORD, KNIFE IN HAND, ATTACKED JOHN WILKES WITH FURY"

"CYRIL SAT UP AND DRANK OFF THE CONTENTS OF THE PANNIKIN"

"FOR HEAVEN'S SAKE, SIR, DO NOT CAUSE TROUBLE"

"TAKE HER DOWN QUICK, JOHN, THERE ARE THREE OTHERS"

"CYRIL RAISED THE KING'S HAND TO HIS LIPS"

"A DUTCH MAN-OF-WAR RAN ALONGSIDE AND FIRED A BROADSIDE"

"FOR THE LAST TIME: WILL YOU SIGN THE DEED?"

"WELCOME BACK TO YOUR OWN AGAIN, SIR CYRIL!"

"WHAT NEWS, JAMES?" THE KING ASKED EAGERLY

WHEN LONDON BURNED

CHAPTER I

FATHERLESS

Lad stood looking out of the dormer window in a scantily furnishedattic in the high-pitched roof of a house in Holborn, in September1664. Numbers of persons were traversing the street below, many ofthem going out through the bars, fifty yards away, into the fieldsbeyond, where some sports were being held that morning, while countrypeople were coming in with their baskets from the villages ofHighgate and Hampstead, Tyburn and Bayswater. But the lad notednothing that was going on; his eyes were filled with tears, and histhoughts were in the little room behind him; for here, coffined inreadiness for burial, lay the body of his father.

Sir Aubrey Shenstone had not been a good father in any sense of theword. He had not been harsh or cruel, but he had altogether neglectedhis son. Beyond the virtues of loyalty and courage, he possessed fewothers. He had fought, as a young man, for Charles, and even amongthe Cavaliers who rode behind Prince Rupert was noted for recklessbravery. When, on the fatal field of Worcester, the last hopes of theRoyalists were crushed, he had effected his escape to France andtaken up his abode at Dunkirk. His estates had been forfeited; andafter spending the proceeds of his wife's jewels and those he hadcarried about with him in case fortune went against the cause forwhich he fought, he sank lower and lower, and had for years lived onthe scanty pension allowed by Louis to the King and his adherents.

Sir Aubrey had been one of the wild, reckless spirits whose conductdid much towards setting the people of England against the cause ofCharles. He gambled and drank, interlarded his conversation withoaths, and despised as well as hated the Puritans against whom hefought. Misfortune did not improve him; he still drank when he hadmoney to do so, gambled for small sums in low taverns with men of hisown kind, and quarrelled and fought on the smallest provocation. Hadit not been for his son he would have taken service in the army ofsome foreign Power; but he could not take the child about with him,nor could he leave it behind.

Sir Aubrey was not altogether without good points. He would dividehis last crown with a comrade poorer than himself. In the worst oftimes he was as cheerful as when money was plentiful, making a jokeof his necessities and keeping a brave face to the world.

Wholly neglected by his father, who spent the greater portion of histime abroad, Cyril would have fared badly indeed had it not been forthe kindness of Lady Parton, the wife of a Cavalier of very differenttype to Sir Aubrey. He had been an intimate friend of Lord Falkland,and, like that nobleman, had drawn his sword with the greatestreluctance, and only when he saw that Parliament was bent uponoverthrowing the other two estates in the realm and constitutingitself the sole authority in England. After the execution of Charleshe had retired to France, and did not take part in the later risings,but lived a secluded life with his wife and children. The eldest ofthese was of the same age as Cyril; and as the latter's mother hadbeen a neighbour of hers before marriage, Lady Parton promised her,on her death-bed, to look after the child, a promise that shefaithfully kept.

Sir John Parton had always been adverse to the association of his boywith the son of Sir Aubrey Shenstone; but he had reluctantly yieldedto his wife's wishes, and Cyril passed the greater portion of histime at their house, sharing the lessons Harry received from anEnglish clergyman who had been expelled from his living by thefanatics of Parliament. He was a good and pious man, as well as anexcellent scholar, and under his teaching, aided by the gentleprecepts of Lady Parton, and the strict but kindly rule of herhusband, Cyril received a training of a far better kind than he wouldever have been likely to obtain had he been brought up in hisfather's house near Norfolk. Sir Aubrey exclaimed sometimes that theboy was growing up a little Puritan, and had he taken more interestin his welfare would undoubtedly have withdrawn him from the healthyinfluences that were benefiting him so greatly; but, with the usualacuteness of children, Cyril soon learnt that any allusion to hisstudies or his life at Sir John Parton's was disagreeable to hisfather, and therefore seldom spoke of them.

Sir Aubrey was never, even when under the influence of his potations,unkind to Cyril. The boy bore a strong likeness to his mother, whomhis father had, in his rough way, really loved passionately. Heseldom spoke even a harsh word to him, and although he occasionallyexpressed his disapproval of

the teaching he was receiving, was atheart not sorry to see the boy growing up so different from himself;and Cyril, in spite of his father's faults, loved him. When SirAubrey came back with unsteady step, late at night, and threw himselfon his pallet, Cyril would say to himself, "Poor father! Howdifferent he would have been had it not been for his misfortunes! Heis to be pitied rather than blamed!" And so, as years went on, inspite of the difference between their natures, there had grown up asort of fellowship between the two; and of an evening sometimes, whenhis father's purse was so low that he could not indulge in his usualstoup of wine at the tavern, they would sit together while Sir Aubreytalked of his fights and adventures.

"As to the estates, Cyril," he said one day, "I don't know thatCromwell and his Roundheads have done you much harm. I should haverun through them, lad--I should have diced them away years ago--and Iam not sure but that their forfeiture has been a benefit to you. Ifthe King ever gets his own, you may come to the estates; while, if Ihad had the handling of them, the usurers would have had such a gripon them that you would never have had a penny of the income."

"It doesn't matter, father," the boy replied. "I mean to be a soldiersome day, as you have been, and I shall take service with some of theProtestant Princes of Germany; or, if I can't do that, I shall beable to work my way somehow."

"What can you work at, lad?" his father said, contemptuously.

"I don't know yet, father; but I shall find some work to do."

Sir Aubrey was about to burst into a tirade against work, but hechecked himself. If Cyril never came into the estates he would haveto earn his living somehow.

"All right, my boy. But do you stick to your idea of earning yourliving by your sword; it is a gentleman's profession, and I wouldrather see you eating dry bread as a soldier of fortune thanprospering in some vile trading business."

Cyril never argued with his father, and he simply nodded an assentand then asked some question that turned Sir Aubrey's thoughts onother matters.

The news that Monk had declared for the King, and that Charles wouldspeedily return to take his place on his father's throne, causedgreat excitement among the Cavaliers scattered over the Continent;and as soon as the matter was settled, all prepared to return toEngland, in the full belief that their evil days were over, and thatthey would speedily be restored to their former estates, with honoursand rewards for their many sacrifices.

"I must leave you behind for a short time, Cyril," his father said tothe boy, when he came in one afternoon. "I must be in London beforethe King arrives there, to join in his welcome home, and for themoment I cannot take you; I shall be busy from morning till night. Ofcourse, in the pressure of things at first it will be impossible forthe King to do everything at once, and it may be a few weeks beforeall these Roundheads can be turned out of the snug nests they havemade for themselves, and the rightful owners come to their own again.As I have no friends in London, I should have nowhere to bestow you,until I can take you down with me to Norfolk to present you to ourtenants, and you would be grievously in my way; but as soon as thingsare settled I will write to you or come over myself to fetch you. Inthe meantime I must think over where I had best place you. It willnot matter for so short a time, but I would that you should be ascomfortable as possible. Think it over yourself, and let me know ifyou have any wishes in the matter. Sir John Parton leaves at the endof the week, and ere another fortnight there will be scarce anotherEnglishman left at Dunkirk."

"Don't you think you can take me with you, father?"

"Impossible," Sir Aubrey said shortly. "Lodgings will be at a greatprice in London, for the city will be full of people from all partscoming up to welcome the King home. I can bestow myself in a garretanywhere, but I could not leave you there all day. Besides, I shallhave to get more fitting clothes, and shall have many expenses. Youare at home here, and will not feel it dull for the short time youhave to remain behind."

Cyril said no more, but went up, with a heavy heart, for his lastday's lessons at the Partons'. Young as he was, he was accustomed tothink for himself, for it was but little guidance he received fromhis father; and after his studies were over he laid the case beforehis master, Mr. Felton, and asked if he could advise him. Mr. Feltonwas himself in high spirits, and was hoping to be speedily reinstatedin his living. He looked grave when Cyril told his story.

"I think it is a pity that your father, Sir Aubrey, does not take youover with him, for it will assuredly take longer to bring all thesematters into order than he seems to think. However, that is hisaffair. I should think he could not do better for you than place youwith the people where I lodge. You know them, and they are a worthycouple; the husband is, as you know, a fisherman, and you and HarryParton have often been out with him in his boat, so it would not belike going among strangers. Continue your studies. I should be sorryto think that you were forgetting all that you have learnt. I willtake you this afternoon, if you like, to my friend, the Cure of St.Ursula. Although we differ on religion we are good friends, andshould you need advice on any matters he will give it to you, and maybe of use in arranging for a passage for you to England, should yourfather not be able himself to come and fetch you."

Sir Aubrey at once assented to the plan when Cyril mentioned it tohim, and a week later sailed for England; Cyril moving, with his fewbelongings, to the house of Jean Baudoin, who was the owner andmaster of one of the largest fishing-boats in Dunkirk. Sir Aubrey hadpaid for his board and lodgings for two months.

"I expect to be over to fetch you long before that, Cyril," he hadsaid, "but it is as well to be on the safe side. Here are fourcrowns, which will furnish you with ample pocket-money. And I havearranged with your fencing-master for you to have lessons regularly,as before; it will not do for you to neglect so important anaccomplishment, for which, as he tells me, you show great aptitude."

The two months passed. Cyril had received but one letter from hisfather. Although it expressed hopes of his speedy restoration to hisestates, Cyril could see, by its tone, that his father was far fromsatisfied with the progress he had made in the matter. Madame Baudoinwas a good and pious woman, and was very kind to the forlorn Englishboy; but when a fortnight over the two months had passed, Cyril couldsee that the fisherman was becoming anxious. Regularly, on his returnfrom the fishing, he inquired if letters had arrived, and seemed muchput out when he heard that there was no news. One day, when Cyril wasin the garden that surrounded the cottage, he heard him say to hiswife,--

"Well, I will say nothing about it until after the next voyage, andthen if we don't hear, the boy must do something for his living. Ican take him in the boat with me; he can earn his victuals in thatway. If he won't do that, I shall wash my hands of him altogether,and he must shift for himself. I believe his father has left him withus for good. We were wrong in taking him only on the recommendationof Mr. Felton. I have been inquiring about his father, and hearlittle good of him."

Cyril, as soon as the fisherman had gone, stole up to his littleroom. He was but twelve years old, and he threw himself down on hisbed and cried bitterly. Then a thought struck him; he went to hisbox, and took out from it a sealed parcel; on it was written, "To myson. This parcel is only to be opened should you find yourself ingreat need, Your Loving Mother." He remembered how she had placed itin his hands a few hours before her death, and had said to him,--

"Put this away, Cyril. I charge you let no one see it. Do not speakof it to anyone--not even to your father. Keep it as a sacred gift,and do not open it unless you are in sore need. It is for you, andyou alone. It is the sole thing that I have to leave you; use it withdiscretion. I fear that hard times will come upon you."

Cyril felt that his need could hardly be sorer than it was now, andwithout hesitation he broke the seals, and opened the packet. Hefound first a letter directed to himself. It began,--

"MY DARLING CYRIL,--I trust that it will be many years before youopen this parcel and read these words. I have left the enclosed as aparting gift to you. I know not how long this exile

may last, orwhether you will ever be able to return to England. But whether youdo or not, it may well be that the time will arrive when you may findyourself in sore need. Your father has been a loving husband to me,and will, I am sure, do what he can for you; but he is not providentin his habits, and may not, after he is left alone, be as careful inhis expenditure as I have tried to be. I fear then that the time willcome when you will be in need of money, possibly even in want of thenecessaries of life. All my other trinkets I have given to him; butthe one enclosed, which belonged to my mother, I leave to you. It isworth a good deal of money, and this it is my desire that you shallspend upon yourself. Use it wisely, my son. If, when you open this,you are of age to enter the service of a foreign Prince, as is, Iknow, the intention of your father, it will provide you with asuitable outfit. If, as is possible, you may lose your father bydeath or otherwise while you are still young, spend it on youreducation, which is the best of all heritages. Should your father bealive when you open this, I pray you not to inform him of it. Themoney, in his hands, would last but a short time, and might, I fear,be wasted. Think not that I am speaking or thinking hardly of him.All men, even the best, have their faults, and his is a carelessnessas to money matters, and a certain recklessness concerning them;therefore, I pray you to keep it secret from him, though I do not saythat you should not use the money for your common good, if it beneedful; only, in that case, I beg you will not inform him as to whatmoney you have in your possession, but use it carefully and prudentlyfor the household wants, and make it last as long as may be. My goodfriend, Lady Parton, if still near you, will doubtless aid you indisposing of the jewels to the best advantage. God bless you, my son!This is the only secret I ever had from your father, but for yourgood I have hidden this one thing from him, and I pray that thisdeceit, which is practised for your advantage, may be forgiven me.YOUR LOVING MOTHER."

It was some time before Cyril opened the parcel; it contained ajewel-box in which was a necklace of pearls. After some considerationhe took this to the Cure of St. Ursula, and, giving him his mother'sletter to read, asked him for his advice as to its disposal.

"Your mother was a thoughtful and pious woman," the good priest said,after he had read the letter, "and has acted wisely in your behalf.The need she foresaw might come, has arisen, and you are surelyjustified in using her gift. I will dispose of this trinket for you;it is doubtless of considerable value. If it should be that yourfather speedily sends for you, you ought to lay aside the money forsome future necessity. If he does not come for some time, as may wellbe--for, from the news that comes from England, it is like to be manymonths before affairs are settled--then draw from it only suchamounts as are needed for your living and education. Study hard, myson, for so will you best be fulfilling the intentions of yourmother. If you like, I will keep the money in my hands, serving itout to you as you need it; and in order that you may keep the mattera secret, I will myself go to Baudoin, and tell him that he need notbe disquieted as to the cost of your maintenance, for that I havemoney in hand with which to discharge your expenses, so long as youmay remain with him."

The next day the Cure informed Cyril that he had disposed of thenecklace for fifty louis. Upon this sum Cyril lived for two years.

Things had gone very hardly with Sir Aubrey Shenstone. The King had adifficult course to steer. To have evicted all those who had obtainedpossession of the forfeited estates of the Cavaliers would have beento excite a deep feeling of resentment among the Nonconformists. Invain Sir Aubrey pressed his claims, in season and out of season. Hehad no powerful friends to aid him; his conduct had alienated the menwho could have assisted him, and, like so many other Cavaliers whohad fought and suffered for Charles I., Sir Aubrey Shenstone foundhimself left altogether in the cold. For a time he was able to keepup a fair appearance, as he obtained loans from Prince Rupert andother Royalists whom he had known in the old days, and who had beenmore fortunate than himself; but the money so obtained lasted but ashort time, and it was not long before he was again in dire straits.

Cyril had from the first but little hope that his father wouldrecover his estates. He had, shortly before his father left France,heard a conversation between Sir John Parton and a gentleman who wasin the inner circle of Charles's advisers. The latter had said,--

"One of the King's great difficulties will be to satisfy the exiles.Undoubtedly, could he consult his own inclinations only, he would onhis return at once reinstate all those who have suffered in theirestates from their loyalty to his father and himself. But this willbe impossible. It was absolutely necessary for him, in hisproclamation at Breda, to promise an amnesty for all offences,liberty of conscience and an oblivion as to the past, and hespecially says that all questions of grants, sales and purchases ofland, and titles, shall be referred to Parliament. The Nonconformistsare at present in a majority, and although it seems that all partiesare willing to welcome the King back, you may be sure that noParliament will consent to anything like a general disturbance of thepossessors of estates formerly owned by Royalists. In a vast numberof cases, the persons to whom such grants were made disposed of themby sale to others, and it would be as hard on them to be ousted as itis upon the original proprietors to be kept out of their possession.Truly it is a most difficult position, and one that will have to beapproached with great judgment, the more so since most of those towhom the lands were granted were generals, officers, and soldiers ofthe Parliament, and Monk would naturally oppose any steps to thedetriment of his old comrades.

"I fear there will be much bitter disappointment among the exiles,and that the King will be charged with ingratitude by those who thinkthat he has only to sign an order for their reinstatement, whereasCharles will have himself a most difficult course to steer, and willhave to govern himself most circumspectly, so as to give offence tonone of the governing parties. As to his granting estates, ordispossessing their holders, he will have no more power to do so thanyou or I. Doubtless some of the exiles will be restored to theirestates; but I fear that the great bulk are doomed to disappointment.At any rate, for a time no extensive changes can be made, though itmay be that in the distance, when the temper of the nation at largeis better understood, the King will be able to do something for thosewho suffered in the cause.

"It was all very well for Cromwell, who leant solely on the Army, todispense with a Parliament, and to govern far more autocraticallythan James or Charles even dreamt of doing; but the Army thatsupported Cromwell would certainly not support Charles. It iscomposed for the most part of stern fanatics, and will be the firstto oppose any attempt of the King to override the law. No doubt itwill erelong be disbanded; but you will see that Parliament will thenrecover the authority of which Cromwell deprived it; and Charles is afar wiser man than his father, and will never set himself against thefeeling of the country. Certainly, anything like a generalreinstatement of the men who have been for the last ten yearshaunting the taverns of the Continent is out of the question; theywould speedily create such a revulsion of public opinion as mightbring about another rebellion. Hyde, staunch Royalist as he is, wouldnever suffer the King to make so grievous an error; nor do I thinkfor a moment that Charles, who is shrewd and politic, and above allthings a lover of ease and quiet, would think of bringing such a nestof hornets about his ears."

When, after his return to England, it became evident that Sir Aubreyhad but small chance of reinstatement in his lands, his formerfriends began to close their purses and to refuse to grant furtherloans, and he was presently reduced to straits as severe as those hehad suffered during his exile. The good spirits that had borne him upso long failed now, and he grew morose and petulant. His loyalty tothe King was unshaken; Charles had several times granted himaudiences, and had assured him that, did it rest with him, justiceshould be at once dealt to him, but that he was practically powerlessin the matter, and the knight's resentment was concentrated uponHyde, now Lord Clarendon, and the rest of the King's advisers. Hewrote but seldom to Cyril; he had no wish to have the boy with himunt

il he could take him down with him in triumph to Norfolk, and showhim to the tenants as his heir. Living from hand to mouth as he did,he worried but little as to how Cyril was getting on.

"The lad has fallen on his feet somehow," he said, "and he is betterwhere he is than he would be with me. I suppose when he wants moneyhe will write and say so, though where I should get any to send tohim I know not. Anyhow, I need not worry about him at present."

Cyril, indeed, had written to him soon after the sale of thenecklace, telling him that he need not distress himself about hiscondition, for that he had obtained sufficient money for his presentnecessities from the sale of a small trinket his mother had given himbefore her death, and that when this was spent he should doubtlessfind some means of earning his living until he could rejoin him. Hisfather never inquired into the matter, though he made a casualreference to it in his next letter, saying that he was glad Cyril hadobtained some money, as it would, at the moment, have beeninconvenient to him to send any over.

Cyril worked assiduously at the school that had been recommended tohim by the Cure, and at the end of two years he had still twentylouis left. He had several conversations with his adviser as to thebest way of earning his living.

"I do not wish to spend any more, Father," he said, "and would fainkeep this for some future necessity."

The Cure agreed with him as to this, and, learning from his masterthat he was extremely quick at figures and wrote an excellent hand,he obtained a place for him with one of the principal traders of thetown. He was to receive no salary for a year, but was to learnbook-keeping and accounts. Although but fourteen, the boy was sointelligent and zealous that his employer told the Cure that he foundhim of real service, and that he was able to entrust some of hisbooks entirely to his charge.

Six months after entering his service, however, Cyril received aletter from his father, saying that he believed his affairs were onthe point of settlement, and therefore wished him to come over in thefirst ship sailing. He enclosed an order on a house at Dunkirk forfifty francs, to pay his passage. His employer parted with him withregret, and the kind Cure bade him farewell in terms of realaffection, for he had come to take a great interest in him.

"At any rate, Cyril," he said, "your time here has not been wasted,and your mother's gift has been turned to as much advantage as evenshe can have hoped that it would be. Should your father's hopes beagain disappointed, and fresh delays arise, you may, with thepractice you have had, be able to earn your living in London. Theremust be there, as in France, many persons in trade who have had butlittle education, and you may be able to obtain employment in keepingthe books of such people, who are, I believe, more common in Englandthan here. Here are the sixteen louis that still remain; put themaside, Cyril, and use them only for urgent necessity."

Cyril, on arriving in London, was heartily welcomed by his father,who had, for the moment, high hopes of recovering his estates. These,however, soon faded, and although Sir Aubrey would not allow it, evento himself, no chance remained of those Royalists, who had, like him,parted with their estates for trifling sums, to be spent in theKing's service, ever regaining possession of them.

It was not long before Cyril perceived that unless he himselfobtained work of some sort they would soon be face to face withactual starvation. He said nothing to his father, but started out onemorning on a round of visits among the smaller class of shopkeepers,offering to make up their books and write out their bills andaccounts for a small remuneration. As he had a frank and pleasantface, and his foreign bringing up had given him an ease andpoliteness of manner rare among English lads of the day, it was notlong before he obtained several clients. To some of the smaller classof traders he went only for an hour or two, once a week, while othersrequired their bills and accounts to be made out daily. The pay wasvery small, but it sufficed to keep absolute want from the door. Whenhe told his father of the arrangements he had made, Sir Aubrey atfirst raged and stormed; but he had come, during the last year ortwo, to recognise the good sense and strong will of his son, andalthough he never verbally acquiesced in what he considered adegradation, he offered no actual opposition to a plan that at leastenabled them to live, and furnished him occasionally with a fewgroats with which he could visit a tavern.

So things had gone on for more than a year. Cyril was now sixteen,and his punctuality, and the neatness of his work, had been soappreciated by the tradesmen who first employed him, that his timewas now fully occupied, and that at rates more remunerative thanthose he had at first obtained. He kept the state of his resources tohimself, and had no difficulty in doing this, as his father neveralluded to the subject of his work. Cyril knew that, did he hand overto him all the money he made, it would be wasted in drink or atcards; consequently, he kept the table furnished as modestly as atfirst, and regularly placed after dinner on the corner of the mantela few coins, which his father as regularly dropped into his pocket.

A few days before the story opens, Sir Aubrey had, late one evening,been carried upstairs, mortally wounded in a brawl; he only recoveredconsciousness a few minutes before his death.

"You have been a good lad, Cyril," he said faintly, as he feeblypressed the boy's hand; "far better than I deserve to have had. Don'tcry, lad; you will get on better without me, and things are just aswell as they are. I hope you will come to your estates some day; youwill make a better master than I should ever have done. I hope thatin time you will carry out your plan of entering some foreignservice; there is no chance here. I don't want you to settle down asa city scrivener. Still, do as you like, lad, and unless your wishesgo with mine, think no further of service."

"I would rather be a soldier, father. I only undertook this workbecause I could see nothing else."

"That is right, my boy, that is right. I know you won't forget thatyou come of a race of gentlemen."

He spoke but little after that. A few broken words came from his lipsthat showed that his thoughts had gone back to old times. "Boot andsaddle," he murmured. "That is right. Now we are ready for them. Downwith the prick-eared knaves! God and King Charles!" These were thelast words he spoke.

Cyril had done all that was necessary. He had laid by more than halfhis earnings for the last eight or nine months. One of his clients,an undertaker, had made all the necessary preparations for thefuneral, and in a few hours his father would be borne to his lastresting-place. As he stood at the open window he thought sadly overthe past, and of his father's wasted life. Had it not been for thewar he might have lived and died a country gentleman. It was the war,with its wild excitements, that had ruined him. What was there forhim to do in a foreign country, without resource or employment,having no love for reading, but to waste his life as he had done? Hadhis wife lived it might have been different. Cyril had still a vividremembrance of his mother, and, though his father had but seldomspoken to him of her, he knew that he had loved her, and that, hadshe lived, he would never have given way to drink as he had done oflate years.

To his father's faults he could not be blind; but they stood fornothing now. He had been his only friend, and of late they had beendrawn closer to each other in their loneliness; and although scarce aword of endearment had passed between them, he knew that his fatherhad cared for him more than was apparent in his manner.

A few hours later, Sir Aubrey Shenstone was laid to rest in a littlegraveyard outside the city walls. Cyril was the only mourner; andwhen it was over, instead of going back to his lonely room, he turnedaway and wandered far out through the fields towards Hampstead, andthen sat himself down to think what he had best do. Another three orfour years must pass before he could try to get service abroad. Whenthe time came he should find Sir John Parton, and beg him to procurefor him some letter of introduction to the many British gentlemenserving abroad. He had not seen him since he came to England. Hisfather had met him, but had quarrelled with him upon Sir Johndeclining to interest himself actively to push his claims, and hadforbidden Cyril to go near those who had been so kind to him.

The boy had felt it greatly at first, but he came, after a time, tosee that it was best so. It seemed to him that he had fallenaltogether out of their station in life when the hope of his father'srecovering his estates vanished, and although he was sure of a kindlyreception from Lady Parton, he shrank from going there in his presentposition. They had done so much for him already, that the thoughtthat his visit might seem to them a sort of petition for furtherbenefits was intolerable to him.

For the present, the question in his mind was whether he shouldcontinue at his present work, which at any rate sufficed to keep him,or should seek other employment. He would greatly have preferred somelife of action,--something that would fit him better to bear thefatigues and hardships of war,--but he saw no prospect of obtainingany such position.

"I should be a fool to throw up what I have," he said to himself atlast. "I will stick to it anyhow until some opportunity offers; butthe sooner I leave it the better. It was bad enough before; it willbe worse now. If I had but a friend or two it would not be so hard;but to have no one to speak to, and no one to think about, when workis done, will be lonely indeed."

At any rate, he determined to change his room as soon as possible. Itmattered little where he went so that it was a change. He thoughtover various tradesmen for whom he worked. Some of them might have anattic, he cared not how small, that they might let him have in lieuof paying him for his work. Even if they never spoke to him, it wouldbe better to be in a house where he knew something of thosedownstairs, than to lodge in one where he was an utter stranger toall. He had gone round to the shops where he worked, on the day afterhis father's death, to explain that he could not come again untilafter the funeral, and he resolved that next morning he would askeach in turn whether he could obtain a lodging with them.

The sun was already setting when he rose from the bank on which hehad seated himself, and returned to the city. The room did not feelso lonely to him as it would have done had he not been accustomed tospending the evenings alone. He took out his little hoard and countedit. After paying the expenses of the funeral there would still remainsufficient to keep him for three or four months should he fall ill,or, from any cause, lose his work. He had one good suit of clothesthat had been bought on his return to England,--when his fatherthought that they would assuredly be going down almost immediately totake possession of the old Hall,--and the rest were all in faircondition.

The next day he began his work again; he had two visits to pay of anhour each, and one of two hours, and the spare time between these hefilled up by calling at two or three other shops to make up for thearrears of work during the last few days.

The last place he had to visit was that at which he had the longesttask to perform. It was at a ship-chandler's in Tower Street, a largeand dingy house, the lower portion being filled with canvas, cordage,barrels of pitch and tar, candles, oil, and matters of all sortsneeded by ship-masters, including many cannon of different sizes,piles of balls, anchors, and other heavy work, all of which werestowed away in a yard behind it. The owner of this store was aone-armed man. His father had kept it before him, but he himself,after working there long enough to become a citizen and a member ofthe Ironmongers' Guild, had quarrelled with his father and had takento the sea. For twenty years he had voyaged to many lands,principally in ships trading in the Levant, and had passed through agreat many adventures, including several fights with the Moorishcorsairs. In the last voyage he took, he had had his arm shot off bya ball from a Greek pirate among the Islands. He had long before madeup his differences with his father, but had resisted the latter'sentreaties that he should give up the sea and settle down at theshop; on his return after this unfortunate voyage he told him that hehad come home to stay.

"I shall be able to help about the stores after a while," he said,"but I shall never be the man I was on board ship. It will be hardwork to take to measuring out canvas and to weighing iron, after afree life on the sea, but I don't so much mind now I have had myshare of adventures; though I dare say I should have gone on for afew more years if that rascally ball had not carried away my arm. Idon't know but that it is best as it is, for the older I got theharder I should find it to fall into new ways and to settle downhere."

"Anyhow, I am glad you are back, David," his father said.

"You are forty-five, and though I don't say it would not have beenbetter if you had remained here from the first, you have learnt manythings you would not have learnt here. You know just the sort ofthings that masters of ships require, and what canvas and cables andcordage will suit their wants. Besides, customers like to talk withmen of their own way of thinking, and sailors more, I think, thanother men. You know, too, most of the captains who sail up theMediterranean, and may be able to bring fresh custom into the shop.Therefore, do not think that you will be of no use to me. As to yourwife and child, there is plenty of room for them as well as for you,and it will be better for them here, with you always at hand, than itwould be for them to remain over at Rotherhithe and only to see youafter the shutters are up."

Eight years later Captain Dave, as he was always called, became soleowner of the house and business. A year after he did so he waslamenting to a friend the trouble that he had with his accounts.

"My father always kept that part of the business in his own hands,"he said, "and I find it a mighty heavy burden. Beyond checking a billof lading, or reading the marks on the bales and boxes, I never hadoccasion to read or write for twenty years, and there has not beenmuch more of it for the last fifteen; and although I was a smartscholar enough in my young days, my fingers are stiff with hauling atropes and using the marling-spike, and my eyes are not so clear asthey used to be, and it is no slight toil and labour to me to make upan account for goods sold. John Wilkes, my head shopman, is a handyfellow; he was my boatswain in the _Kate_, and I took him on when wefound that the man who had been my father's right hand for twentyyears had been cheating him all along. We got on well enough as longas I could give all my time in the shop; but he is no good with thepen--all he can do is to enter receipts and sales.

"He has a man under him, who helps him in measuring out the rightlength of canvas and cables or for weighing a chain or an anchor, andknows enough to put down the figures; but that is all. Then there arethe two smiths and the two apprentices; they don't count in thematter. Robert Ashford, the eldest apprentice, could do the work, butI have no fancy for him; he does not look one straight in the face asone who is honest and above board should do. I shall have to keep aclerk, and I know what it will be--he will be setting me right, and Ishall not feel my own master; he will be out of place in my crewaltogether. I never liked pursers; most of them are rogues. Still, Isuppose it must come to that."

"I have a boy come in to write my bills and to make up my accounts,who would be just the lad for you, Captain Dave. He is the son of abroken-down Cavalier, but he is a steady, honest young fellow, and Ifancy his pen keeps his father, who is a roystering blade, and spendsmost of his time at the taverns. The boy comes to me for an hour,twice a week; he writes as good a hand as any clerk and can reckon asquickly, and I pay him but a groat a week, which was all he asked."

"Tell him to come to me, then. I should want him every day, if hecould manage it, and it would be the very thing for me."

"I am sure you would like him," the other said; "he is a good-lookingyoung fellow, and his face speaks for him without any recommendation.I was afraid at first that he would not do for me; I thought therewas too much of the gentleman about him. He has good manners, and agentle sort of way. He has been living in France all his life, andthough he has never said anything about his family--indeed he talksbut little, he just comes in and does his work and goes away--I fancyhis father was one of King Charles's men and of good blood."

"Well, that doesn't sound so well," the sailor said, "but anyhow Ishould like to have a look at him."

"He comes to me to-morrow at eleven and goes at twelve," the mansaid, "and I will send him round to you when he has done."

Cyril had gone round the next morning to the ships' store.

"So you are the lad that works for my neighbour Anderson?" CaptainDave said, as he surveyed him closely. "I like your looks, lad, but Idoubt whether we shall get on together. I am an old sailor, you know,and I am quick of speech and don't stop to choose my words, so if youare quick to take offence it would be of no use your coming to me."

"I don't think I am likely to take offence," Cyril said quietly; "andif we don't get on well together, sir, you will only have to tell methat you don't want me any longer; but I trust you will not haveoften the occasion to use hard words, for at any rate I will do mybest to please you."

"You can't say more, lad. Well, let us have a taste of your quality.Come in here," and he led him into a little room partitioned off fromthe shop. "There, you see," and he opened a book, "is the account ofthe sales and orders yesterday; the ready-money sales have got to beentered in that ledger with the red cover; the sales where no moneypassed have to be entered to the various customers or ships in theledger. I have made out a list--here it is--of twelve accounts thathave to be drawn out from that ledger and sent in to customers. Youwill find some of them are of somewhat long standing, for I have beenputting off that job. Sit you down here. When you have done one ortwo of them I will have a look at your work, and if that issatisfactory we will have a talk as to what hours you have gotdisengaged, and what days in the week will suit you best."

It was two hours before Captain Dave came in again. Cyril had justfinished the work; some of the accounts were long ones, and thewriting was so crabbed that it took him some time to decipher it.

"Well, how are you getting on, lad?" the Captain asked.

"I have this moment finished the last account."

"What! Do you mean to say that you have done them all! Why, it wouldhave taken me all my evenings for a week. Now, hand me the books; itis best to do things ship-shape."

He first compared the list of the sales with the entries, and thenCyril handed him the twelve accounts he had drawn up. Captain Daviddid not speak until he had finished looking through them.

"I would not have believed all that work could have been done in twohours," he said, getting up from his chair. "Orderly and wellwritten, and without a blot. The King's secretary could not have donebetter! Well, now you have seen the list of sales for a day, and Itake it that be about the average, so if you come three times a weekyou will always have two days' sales to enter in the ledger. Thereare a lot of other books my father used to keep, but I have never hadtime to bother myself about them, and as I have got on very well sofar, I do not see any occasion for you to do so, for my part it seemsto me that all these books are only invented by clerks to givethemselves something to do to fill up their time. Of course, therewon't be accounts to send out every day. Do you think with two hours,three times a week, you could keep things straight?"

"I should certainly think so, sir, but I can hardly say until I try,because it seems to me that there must be a great many items, and Ican't say how long it will take entering all the goods received undertheir proper headings; but if the books are thoroughly made up now, Ishould think I could keep them all going."

"That they are not," Captain David said ruefully; "they are allhorribly in arrears. I took charge of them myself three years ago,and though I spend three hours every evening worrying over them, theyget further and further in arrears. Look at those files over there,"and he pointed to three long wires, on each of which was strung alarge bundle of papers; "I am afraid you will have to enter them allup before you can get matters into ship-shape order. The daily salebook is the only one that has been kept up regularly."

"But these accounts I have made up, sir? Probably in those filesthere are many other goods supplied to the same people."

"Of course there are, lad, though I did not think of it before. Well,we must wait, then, until you can make up the arrears a bit, though Ireally want to get some money in."

"Well, sir, I might write at the bottom of each bill 'Account made upto,' and then put in the date of the latest entry charged."

"That would do capitally, lad--I did not think of that. I see youwill be of great use to me. I can buy and sell, for I know the valueof the goods I deal in; but as to accounts, they are altogether outof my way. And now, lad, what do you charge?"

"I charge a groat for two hours' work, sir; but if I came to youthree times a week, I would do it for a little less."

"No, lad, I don't want to beat you down; indeed, I don't think youcharge enough. However, let us say, to begin with, three groats aweek."

This had been six weeks before Sir Aubrey Shenstone's death; and inthe interval Cyril had gradually wiped off all the arrears, and hadall the books in order up to date, to the astonishment of hisemployer.