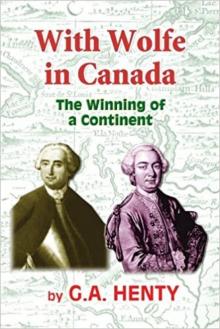

With Wolfe in Canada: The Winning of a Continent

G. A. Henty

E-text prepared by Martin Robb

WITH WOLFE IN CANADA

Or The Winning of a Continent

by

G. A. Henty

1894

CONTENTS:

Preface. Chapter 1: A Rescue. Chapter 2: The Showman's Grandchild. Chapter 3: The Justice Room. Chapter 4: The Squire's Granddaughter. Chapter 5: A Quiet Time. Chapter 6: A Storm. Chapter 7: Pressed. Chapter 8: Discharged. Chapter 9: The Defeat Of Braddock. Chapter 10: The Fight At Lake George. Chapter 11: Scouting. Chapter 12: A Commission. Chapter 13: An Abortive Attack. Chapter 14: Scouting On Lake Champlain. Chapter 15: Through Many Perils. Chapter 16: The Massacre At Fort William Henry. Chapter 17: Louisbourg And Ticonderoga. Chapter 18: Quebec. Chapter 19: A Dangerous Expedition. Chapter 20: The Path Down The Heights. Chapter 21: The Capture Of Quebec.

Preface.

My Dear Lads,

In the present volume I have endeavoured to give the details of theprincipal events in a struggle whose importance can hardly beoverrated. At its commencement the English occupied a mere patch ofland on the eastern seaboard of America, hemmed in on all sides by theFrench, who occupied not only Canada in the north and Louisiana in thesouth, but possessed a chain of posts connecting them, so cutting offthe English from all access to the vast countries of the west.

On the issues of that struggle depended not only the destiny of Canada,but of the whole of North America and, to a large extent, that of thetwo mother countries. When the contest began, the chances of Francebecoming the great colonizing empire of the world were as good as thoseof England. Not only did she hold far larger territories in Americathan did England, but she had rich colonies in the West Indies, wherethe flag of England was at that time hardly represented, and herprospects in India were better than our own. At that time, too, shedisputed with us on equal terms the empire of the sea.

The loss of her North American provinces turned the scale. With themonopoly of such a market, the commerce of England increasedenormously, and with her commerce her wealth and power of extension,while the power of France was proportionately crippled. It is truethat, in time, the North American colonies, with the exception ofCanada, broke away from their connection with the old country; but theystill remained English, still continued to be the best market for ourgoods and manufactures.

Never was the short-sightedness of human beings shown more distinctly,than when France wasted her strength and treasure in a sterile conteston the continent of Europe, and permitted, with scarce an effort, herNorth American colonies to be torn from her.

All the historical details of the war have been drawn from theexcellent work entitled Montcalm and Wolfe, by Mr. Francis Parkman, andfrom the detailed history of the Louisbourg and Quebec expeditions, byMajor Knox, who served under Generals Amherst and Wolfe.

Yours very sincerely,

G. A. Henty.

Chapter 1: A Rescue.

Most of the towns standing on our seacoast have suffered a radicalchange in the course of the last century. Railways, and the fashion ofsummer holiday making, have transformed them altogether, and greattowns have sprung up where fishing villages once stood. There are a fewplaces, however, which seem to have been passed by, by the crowd. Thenumber yearly becomes smaller, as the iron roads throw out freshbranches. With the advent of these comes the speculative builder. Rowsof terraces and shops are run up, promenades are made, bathing machinesand brass bands become familiar objects, and in a few years theoriginal character of the place altogether disappears.

Sidmouth, for a long time, was passed by, by the world of holidaymakers. East and west of her, great changes took place, and many farsmaller villages became fashionable seaside watering places. Therailway, which passed by some twelve miles away, carried its tens ofthousands westward, but left few of them for Sidmouth, and anyone whovisited the pretty little place, fifteen years back, would have seen italmost as it stood when our story opens a century ago.

There are few places in England with a fairer site. It lies embosomedin the hills, which rise sharply on either side of it, while behindstretches a rich, undulating country, thickly dotted with orchards andsnug homesteads, with lanes bright with wildflowers and ferns, withhigh hedges and trees meeting overhead. The cold breezes, which renderso bare of interest the walks round the great majority of our seasidetowns, pass harmlessly over the valley of the Sid, where the vegetationis as bright and luxuriant as if the ocean lay leagues away, instead ofbreaking on the shore within a few feet of the front line of houses.

The cliffs which, on either side, rise from the water's edge, areneither white like those to the east, nor grey as are the ruggedbulwarks to the west. They are of a deep red, warm and pleasant to theeye, with clumps of green showing brightly up against them on everylittle ledge where vegetation can get a footing; while the beach isneither pebble, nor rock, nor sand, but a smooth, level surface slopingevenly down; hard and pleasant to walk on when the sea has gone down,and the sun has dried and baked it for an hour or two; but slippery andtreacherous when freshly wetted, for the red cliffs are of clay. Thosewho sail past in a boat would hardly believe that this is so, for thesun has baked its face, and the wind dried it, till it is cracked andseamed, and makes a brave imitation of red granite; but the clammyooze, when the sea goes down, tells its nature only too plainly, andSidmouth will never be a popular watering place for children, for thereis no digging sand castles here, and a fall will stain light dressesand pinafores a ruddy hue, and the young labourers will look as if theyhad been at work in a brick field.

But a century since, the march of improvement had nowhere begun; andthere were few larger, and no prettier, seaside villages on the coastthan Sidmouth.

It was an afternoon in August. The sun was blazing down hotly, scarce abreath of wind was stirring, and the tiny waves broke along the shorewith a low rustle like that of falling leaves. Some fishermen were atwork, recaulking a boat hauled up on the shore. Others were laying outsome nets to dry in the sun. Some fisher boys were lying asleep, likedogs basking in the heat; and a knot of lads, sitting under the shadeof a boat, were discussing with some warmth the question of smuggling.

"What do you say to it, Jim Walsham?" one of the party said, looking upat a boy some twelve years old, who was leaning against a boat, but whohad hitherto taken no part in the discussion.

"There is no doubt that it's wrong," the boy said. "Not wrong likestealing, and lying, and that sort of thing; still it's wrong, becauseit's against the law; and the revenue men, if they come upon a ganglanding the tubs, fight with them, and if any are killed they are notblamed for it, so there is no doubt about its being wrong. Then, on theother hand, no one thinks any the worse of the men that do it, andthere is scarce a one, gentle or simple, as won't buy some of the stuffif he gets a chance, so it can't be so very wrong. It must be great funto be a smuggler, to be always dodging the king's cutters, and runningcargoes under the nose of the officers ashore. There is some excitementin a life like that."

"There is plenty of excitement in fishing," one of the boys saidsturdily. "If you had been out in that storm last March, you would havehad as much excitement as you liked. For twelve hours we expected to godown every minute, and we were half our time bailing for our lives."

An approving murmur broke from the others, who were all, with theexception of the one addressed as Jim Walsham, of the fisher class. Hisclothing differed but little from that of the rest. His dark blue pilottrousers were old and sea stained, his hands and face were dyed brownwith exposure to the sun and the salt water; but there was something,in his manner and tone of voice, which showed that

a distinctionexisted.

James Walsham was, indeed, the son of the late doctor of the village,who had died two years previously. Dr. Walsham had been clever in hisprofession, but circumstances were against him. Sidmouth and itsneighbourhood were so healthy, that his patients were few and farbetween; and when he died, of injuries received from being thrown overhis horse's head, when the animal one night trod on a stone coming downthe hill into Sidmouth, his widow and son were left almost penniless.

Mrs. Walsham was, fortunately, an energetic woman, and a fortnightafter her husband's death, she went round among the tradesmen of theplace and the farmers of the neighbourhood, and announced her intentionof opening a school for girls. She had received a good education, beingthe daughter of a clergyman, and she soon obtained enough pupils toenable her to pay her way, and to keep up the pretty home in which herhusband lived in the outskirts of Sidmouth.

If she would have taken boarders, she could have obtained far higherterms, for good schools were scarce; but this she would not do, and herpupils all lived within distances where they could walk backwards andforwards to their homes. Her evenings she devoted to her son, and,though the education which she was enabled to give him would beconsidered meagre, indeed, in these days of universal cramming, helearned as much as the average boy of the period.

He would have learned more had he followed her desires, and devoted thetime when she was engaged in teaching to his books; but this he did notdo. For a few hours in the day he would work vigorously at his lessons.The rest of his time he spent either on the seashore, or in the boatsof the fishermen; and he could swim, row, or handle a boat under sailin all weather, as well or better than any lad in the village of hisown age.

His disposition was a happy one, and he was a general favourite amongthe boatmen. He had not, as yet, made up his mind as to his future. Hismother wanted him to follow his father's profession. He himself longedto go to sea, but he had promised his mother that he would never do sowithout her consent, and that consent he had no hope of obtaining.

The better-class people in the village shook their heads gravely overJames Walsham, and prophesied no good things of him. They consideredthat he demeaned himself greatly by association with the fisher boys,and more than once he had fallen into disgrace, with the more quietminded of the inhabitants, by mischievous pranks. His reputation thatway once established, every bit of mischief in the place, which couldnot be clearly traced to someone else, was put down to him; and as hewas not one who would peach upon others to save himself, he was seldomin a position to prove his innocence.

The parson had once called upon Mrs. Walsham, and had talked to hergravely over her son's delinquencies, but his success had not beenequal to his anticipations. Mrs. Walsham had stood up warmly for herson.

"The boy may get into mischief sometimes, Mr. Allanby, but it is thenature of boys to do so. James is a good boy, upright and honourable,and would not tell a lie under any consideration. What is he to do? IfI could afford to send him to a good school it would be a differentthing, but that you know I cannot do. From nine in the morning, untilfive in the afternoon, my time is occupied by teaching, and I cannotexpect, nor do I wish, that he should sit moping indoors all day. Hehad far better be out in the boats with the fishermen, than be hangingabout the place doing nothing. If anything happened to me, before he isstarted in life, there would be nothing for him but to take to the sea.I am laying by a little money every month, and if I live for anotheryear there will be enough to buy him a fishing boat and nets. I trustthat it may not come to that, but I see nothing derogatory in hisearning an honest living with his own hands. He will always besomething better than a common fisherman. The education I have strivento give him, and his knowledge that he was born a gentleman, will nervehim to try and rise.

"As to what you say about mischief, so far as I know all boys aremischievous. I know that my own brothers were always getting intoscrapes, and I have no doubt, Mr. Allanby, that when you look back uponyour own boyhood, you will see that you were not an exception to thegeneral rule."

Mr. Allanby smiled. He had come rather against his own inclinations;but his wife had urged him to speak to Mrs. Walsham, her temper beingruffled by the disappearance of two favourite pigeons, whose loss she,without a shadow of evidence, most unjustly put down to James Walsham.

The parson was by no means strict with his flock. He was a tall man,inclined to be portly, a good shot and an ardent fisherman; andalthough he did not hunt, he was frequently seen on his brown cob atthe meet, whenever it took place within a reasonable distance ofSidmouth; and without exactly following the hounds, his knowledge ofthe country often enabled him to see more of the hunt than those whodid.

As Mrs. Walsham spoke, the memory of his old school and college dayscame across him.

"That is the argumentum ad hominem, Mrs. Walsham, and when a lady takesto that we can say no more. You know I like your boy. There is muchthat is good in him; but it struck me that you were letting him run alittle too wild. However, there is much in what you say, and I don'tbelieve that he is concerned in half the mischief that he gets creditfor. Still, you must remember that a little of the curb, just a little,is good for us all. It spoils a horse to be always tugging at hismouth, but he will go very badly if he does not feel that there is ahand on the reins.

"I have said the same thing to the squire. He spoils that boy of his,for whom, between ourselves, I have no great liking. The old man willhave trouble with him before he is done, or I am greatly mistaken."

Nothing came of Mr. Allanby's visit. Mrs. Walsham told James that hehad been there to remonstrate with her.

"I do not want to stop you from going out sailing, Jim; but I wish youwould give up your mischievous pranks, they only get you bad will and abad name in the place. Many people here think that I am wrong inallowing you to associate so much with the fisher boys, and when youget into scrapes, it enables them to impress upon me how right theywere in their forecasts. I do not want my boy to be named in the samebreath with those boys of Robson's, or young Peterson, or Blame."

"But you know I have nothing to do with them, mother," James saidindignantly. "They spend half their time about the public house, andthey do say that when Peterson has been out with that lurcher of his,he has been seen coming back with his coat bulged out, and there isoften a smell of hare round his father's cottage at supper time. Youknow I wouldn't have anything to do with them."

"No, Jim, I am sure you would not; but if people mix up your name withtheirs it is almost as bad for you as if you had. Unfortunately, peopleare too apt not to distinguish between tricks which are really only theoutcome of high spirit, and a lack of something better to do, and realvice. Therefore, Jim, I say, keep yourself from mischief. I know that,though you are out of doors so many hours of the day, you really do getthrough a good deal of work; but other people do not give you creditfor this. Remember how your father was respected here. Try to actalways as you would have done had he been alive, and you cannot go farwrong."

James had done his best, but he found it hard to get rid of hisreputation for getting into mischief, and more than once, when falselysuspected, he grumbled that he might just as well have the fun of thething, for he was sure to have the blame.

As Jim Walsham and his companions were chatting in the shade of a boat,their conversation was abruptly broken off by the sight of a figurecoming along the road. It was a tall figure, with a stiff militarybearing. He was pushing before him a large box, mounted on a frameworksupported by four wheels. Low down, close to the ground, swung a largeflat basket. In this, on a shawl spread over a thick bed of hay, sat alittle girl some five years old.

"It is the sergeant," one of the boys exclaimed. "I wonder whether hehas got a fresh set of views? The last were first-rate ones."

The sergeant gave a friendly nod to the boys as he passed, and then,turning up the main street from the beach, went along until he came toa shaded corner, and there stopped. The boys had all got up andfollowed him, and now stood looking o

n with interest at hisproceedings. The little girl had climbed out of her basket as soon ashe stopped, and after asking leave, trotted back along the street tothe beach, and was soon at play among the seaweed and stones.

She was a singularly pretty child, with dark blue eyes, and brown hairwith a touch of gold. Her print dress was spotlessly clean and neat; ahuge flapping sunbonnet shaded her face, whose expression was brightand winning.

"Well, boys," the sergeant said cheerfully, "how have you been gettingon since I was here last? Nobody drowned, I hope, or come to any ill.Not that we must grumble, whatever comes. We have all got to do ourduty, whether it be to march up a hill with shot and shell screamingand whistling round, as I have had to do; or to be far out at sea withthe wind blowing fit to take the hair off your head, as comes to yourlot sometimes; or following the plough from year's end to year's end,as happens to some. We have got to make the best of it, whatever it is.

"I have got a grand new set of pictures from Exeter. They came all theway down from London town for me by waggon. London Bridge, and WindsorCastle, with the flag flying over it, telling that the king--God blesshis gracious majesty--is at home.

"Then, I have got some pictures of foreign parts that will make youopen your eyes. There's Niagara. I don't know whether you've heard ofit, but it's a place where a great river jumps down over a wall ofrock, as high as that steeple there, with a roar like thunder that canbe heard, they say, on a still night, for twenty miles round.

"I have got some that will interest you more still, because you aresailors, or are going to be sailors. I have got one of the killing of awhale. He has just thrown a boat, with five sailors, into the air, witha lash of his tail; but it's of no use, for there are other boatsround, and the harpoons are striking deep in his flesh. He is a bigfish, and a strong one; but he will be beaten, for he does not know howto use his strength. That's the case with many men. They throw awaytheir life and their talents, just because they don't know what's inthem, and what they might do if they tried.

"And I have got a picture of the fight with the Spanish Armada. Youhave heard about that, boys, surely; for it began out there, over thewater, almost in sight of Sidmouth, and went on all the way up theChannel; our little ships hanging on to the great Spaniards and givingthem no rest, but worrying them, and battering them, till they wereglad to sail away to the Dutch coast. But they were not safe there, forwe sent fire ships at them, and they had to cut and run; and then astorm came on, and sunk many, and drove others ashore all around ourcoasts, even round the north of Scotland and Ireland.

"You will see it all here, boys, and as you know, the price is only onepenny."

By this time, the sergeant had let down one side of the box anddiscovered four round holes, and had arranged a low stool in front, forany of those, who were not tall enough to look through the glasses, tostand upon. A considerable number of girls and boys had now gatheredround, for Sergeant Wilks and his show were old, established favouritesat Sidmouth, and the news of his arrival had travelled quickly roundthe place.

Four years before, he had appeared there for the first time, and sincethen had come every few months. He travelled round the southwesterncounties, Dorset and Wilts, Somerset, Devon, and Cornwall, and hischeery good temper made him a general favourite wherever he went.

He was somewhat of a martinet, and would have no crowding and pushing,and always made the boys stand aside till the girls had a good look;but he never hurried them, and allowed each an ample time to see thepictures, which were of a better class than those in most travellingpeep shows. There was some murmuring, at first, because the showcontained none of the popular murders and blood-curdling scenes towhich the people were accustomed.

"No," the sergeant had said firmly, when the omission was suggested tohim; "the young ones see quite enough scenes of drunkenness andfighting. When I was a child, I remember seeing in a peep show thepicture of a woman lying with her head nearly cut off, and her husbandwith a bloody chopper standing beside her; and it spoiled my sleep forweeks. No, none of that sort of thing for Sergeant Wilks. He has foughtfor his country, and has seen bloodshed enough in his time, and theground half covered with dead and dying men; but that was duty--this ispleasure. Sergeant Wilks will show the boys and girls, who pay himtheir pennies, views in all parts of the world, such as would cost themthousands of pounds if they travelled to see them, and all as naturalas life. He will show them great battles by land and sea, where thesoldiers and sailors shed their blood like water in the service oftheir country. But cruel murders and notorious crimes he will not showthem."

It was not the boys and girls, only, who were the sergeant's patrons.Picture books were scarce in those days, and grown-up girls and youngmen were not ashamed to pay their pennies to peep into the sergeant'sbox.

There was scarcely a farm house throughout his beat where he was notknown and welcomed. His care of the child, who, when he first cameround, was but a year old, won the heart of the women; and a bowl ofbread and milk for the little one, and a mug of beer and a hunch ofbread and bacon for himself, were always at his service, before heopened his box and showed its wonders to the maids and children of thehouse.

Sidmouth was one of his regular halting places, and, indeed, he visitedit more often than any other town on his beat. There was always a roomready for him there, in the house of a fisherman's widow, when hearrived on the Saturday, and he generally stopped till the Monday. Thushe had come to know the names of most of the boys of the place, as wellas of many of the elders; for it was his custom, of a Saturday evening,after the little one was in bed, to go and smoke his pipe in thetaproom of the "Anchor," where he would sometimes relate tales of hisadventures to the assembled fishermen. But, although chatty and cheerywith his patrons, Sergeant Wilks was a reticent, rather than atalkative, man. At the "Anchor" he was, except when called upon for astory, a listener rather than a talker.

As to his history, or the county to which he belonged, he never alludedto it, although communicative enough as to his military adventures; andany questions which were asked him, he quietly put on one side. He hadintimated, indeed, that the father and mother of his grandchild wereboth dead; but it was not known whether she was the child of his son ordaughter; for under his cheerful talk there was something of militarystrictness and sternness, and he was not a man of whom idle questionswould be asked.

"Now, boys and girls," he said, "step up; the show is ready. Those whohave got a penny cannot spend it better. Those who haven't must try andget their father or mother to give them one, and see the show later on.Girls first. Boys should always give way to their sisters. The bravestmen are always the most courteous and gentle with women."

Four girls, of various ages, paid their pennies and took their placesat the glasses, and the sergeant then began to describe the pictures,his descriptions of the wonders within being so exciting, that severalboys and girls stole off from the little crowd, and made their way totheir homes to coax their parents out of the necessary coin.

James Walsham listened a while, and then walked away to the sea, forthere would be several sets of girls before it came to the turn of theboys. He strolled along, and as he came within sight of the beachstopped for a moment suddenly, and then, with a shout, ran forward atthe top of his speed.

The little girl, after playing some time with the seaweed, had climbedinto a small boat which lay at the edge of the advancing tide, and,leaning over the stern, watched the little waves as they ran up oneafter another. A few minutes after she had got into it, the rising tidefloated the boat, and it drifted out a few yards, as far as itsheadrope allowed it. Ignorant of what had happened, the child waskneeling up at the stern, leaning over, and dabbling her hands in thewater.

No one had noticed her. The boys had all deserted the beach. None ofthe fishermen were near the spot.

Just before James Walsham came within sight of the sea, the child hadoverbalanced itself. His eye fell on the water just as two arms and afrightened little face appeared above it. There was

a little splash,and a struggle, and the sea was bare again.

At the top of his speed James dashed across the road, sprang down thebeach, and, rushing a few yards into the water, dived down. He knewwhich way the tide was making, and allowed for the set. A few vigorousstrokes, and he reached something white on the surface. It was thesunbonnet which had, in the child's struggles, become unfastened. Hedived at once, and almost immediately saw a confused mass before him.Another stroke, and he seized the child's clothes, and, grasping herfirmly, rose to the surface and swam towards shore.

Although the accident had not been perceived, his shout and sudden rushinto the water had called the attention of some of the men, and two orthree of them ran into the water, waist deep, to help him out with hislittle burden.

"Well done, Master Walsham! The child would have been drowned if youhad not seed it. None of us noticed her fall over. She was playing onthe beach last time I seed her."

"Is she dead?" James asked, breathless from his exertions.

"Not she," the fisherman said. "She could not have been under water aminute. Take her into my cottage, it's one of the nighest. My wife willput her between the blankets, and will soon bring her round."

The fisherman's wife met them at the door, and, taking the child fromthe lad, carried it in, and soon had her wrapped up in blankets. Butbefore this was done she had opened her eyes, for she had scarcely lostconsciousness when James had seized her.

The lad stood outside the door, waiting for the news, when the sergeanthurried up, one of the fishermen having gone to tell him what hadhappened, as soon as the child had been carried into thecottage--assuring him, as he did so, that the little one would speedilycome round.

Just as he came up the door of the cottage opened, and one of thewomen, who had run in to assist the fisherman's wife, put her head out.

"She has opened her eyes," she said. "The little dear will soon be allright."

"Thank God for His mercies!" the sergeant said, taking off his hat."What should I have done if I had lost her?

"And I have to thank you, next to God," he said, seizing the boy'shand. "May God bless you, young gentleman! and reward you for havingsaved my darling. They tell me she must have been drowned, but for you,for no one knew she had fallen in. Had it not been for you, I shouldcome round to look for her, and she would have been gone--goneforever!" and the showman dashed the tears from his eyes with the backof his hand.

"I was only just in time," the lad said. "I did not see her fall out ofthe boat. She was only a few yards away from it when she came up--justas my eyes fell on the spot. I am very glad to have saved her for you;but, of course, it was nothing of a swim. She could not have been manyyards out of my depth. Now I will run home and change my things."

James Walsham was too much accustomed to be wet through, to careanything about his dripping clothes, but they served him as an excuseto get away, for he felt awkward and embarrassed at the gratitude ofthe old soldier. He pushed his way through the little crowd, which hadnow gathered round, and started at a run; for the news had broughtalmost all those gathered round the peep show to the shore, theexcitement of somebody being drowned being superior even to that of thepeep show, to the great majority; though a few, who had no hope ofobtaining the necessary pennies, had lingered behind, and seized theopportunity for a gratuitous look through the glasses.

James ran upstairs and changed his clothes without seeing his mother,and then, taking down one of his lesson books, set to work, shrinkingfrom the idea of going out again, and being made a hero of.

Half an hour later there was a knock at the front door, and a fewminutes after his mother called him down. He ran down to the parlour,and there found the showman.

"Oh, I say," the boy broke out, "don't say anything more about it! I dohate being thanked, and there was nothing in swimming ten yards in acalm sea. Please don't say anything more about it. I would rather youhit me, ever so much."

The sergeant smiled gravely, and Mrs. Walsham exclaimed:

"Why didn't you come in and tell me about it, Jim? I could not make outat first what Mr.--Mr.--"

"Sergeant Wilks, madam."

"What Sergeant Wilks meant, when he said that he had called to tell mehow grateful he felt to you for saving his little grandchild's life. Iam proud of you, Jim."

"Oh, mother, don't!" the boy exclaimed. "It is horrid going on so. If Ihad swum out with a rope through the surf, there might be something init; but just to jump in at the edge of the water is not worth making afuss about, one way or the other."

"Not to you, perhaps, young gentleman, but it is to me," the showmansaid. "The child is the light of my life, the only thing I have to carefor in the world, and you have saved her. If it had only been bystretching out your hand, I should have been equally grateful. However,I will say no more about it, but I shall not think the less.

"But don't you believe, madam, that there was no credit in it. It wasjust the quickness and the promptness which saved her life. Had yourson hesitated a moment it would have been too late, for he would neverhave found her. It is not likely that your son will ever have anyoccasion for help of mine, but should there be an opportunity, he mayrely upon it that any service I can render him shall be his to thedeath; and, unlikely as it may seem, it may yet turn out that thisbrave act of his, in saving the life of the granddaughter of atravelling showman, will not be without its reward."

"Is she all right now?" James asked abruptly, anxious to change theconversation.

"Yes. She soon came to herself, and wanted to tell me all about it; butI would not let her talk, and in a few minutes she dropped off tosleep, and there I left her. The women tell me she will probably sleeptill morning, and will then be as well as ever. And now I must go andlook after my box, or the boys will be pulling it to pieces."

It was, however, untouched, for in passing the sergeant had told thelittle crowd that, if they left it alone, he would, on his return, letall see without payment; and during the rest of the afternoon he wasfully occupied with successive audiences, being obliged to make hislectures brief, in order that all might have their turn.

After the sergeant had left, James took his hat and went for a longwalk in the country, in order to escape the congratulations of theother boys. The next day little Agnes was perfectly well, and appearedwith her grandfather in the seat, far back in the church, which healways occupied on the Sundays he spent at Sidmouth. On these occasionsshe was always neatly and prettily dressed, and, indeed, some of thegood women of the place, comparing the graceful little thing with theirown children, had not been backward in their criticisms on the folly ofthe old showman, in dressing his child out in clothes fit for a lady.