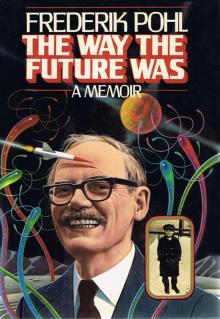

The Way the Future Was: A Memoir

Frederik Pohl

Award-winning writer, whiz-kid editor, wide-eyed fan, pioneering anthologist and demon literary agent—Frederik Pohl’s been all over the science-fiction field, including a stretch as President of The Science Fiction Writers of America.

Here is his story of how he got to all those places and what it was like getting there.

In it you will find…

What Isaac Asimov was like at 19.

The truth behind the great World SF Convention War of 1939.

How a teenager became a mover and shaker in the bizarre world of the pulp magazines.

The strange mating rites of the sf community.

How to represent most of the best sf writers and go broke.

The dreams of new worlds and universes behind a body of completely original writing that has enlarged the horizons of three generations of readers…and netted the writers ½¢ to 3¢ a word.

From the moment he attended the first meeting of the Brooklyn chapter of the Science Fiction League, Fred Pohl was hooked. He and his friends founded and disbanded fan clubs with dizzying speed then organized the fabled Futurians. At 19, he became editor of Astonishing Stories and Super Science Stories and except for the war and a brief fling in the advertising business, has been almost totally involved in science fiction ever since.

As an agent he created the market for hardcover sf; as editor of Galaxy in the 60s, he shaped the field for most of a decade; his Star Science Fiction series pioneered the concept of original anthologies; and along with all that he produced a number of truly outstanding works of sf, including: The Space Merchants (with Cyril Kornbluth) and, most recently Man Plus and Gateway, voted the Best Novels of 1976 and 1977, respectively.

It’s been a long road, from the scruffy Ivory Tower where the Futurians denned to a time when much that was science fiction is now reality—and Fred Pohl retraces it with candor, wit, and abiding love.

A Del Rey Book

Published by Ballantine Books

Copyright © 1978 by Frederik Pohl

Photo credits:

Jay Kay Klein: p. 5, bottom; p. 6, bottom; p. 9; p. 10; p. 11, top; p. 12; p. 13; p. 14, top; p. 16.

All other photographs are from the author’s personal collection.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Ballantine Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Ballantine Books of Canada, Ltd., Toronto, Canada.

Manufactured in the United States of America

First Edition: August 1978

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Pohl, Frederik.

The way the future was.

1. Pohl, Frederik. 2. Authors, American—20th Century—Biography. 3. Science fiction, American—History and criticism. I. Title.

PS3566.036Z47 813'.5'4 [B] 78-19050

ISBN 0-345-27714-7

For Carol,

who shared in so much of it,

and made it so much nicer.

Contents

As It Was in the Beginning

Let There Be Fandom

Science-fiction Samizdat

Boy Bolsheviks

The Futurians

Nineteen Years Old, and God

My Life as a Cardinal Man

Ten Percent of a Writer

Four Pages a Day

The Finest Job in the World

Have Mouth, Will Travel

How I Re-upped with the World

1

As It Was in the Beginning

When I first encountered science fiction, Herbert Hoover was the President of the United States, a plump, perplexed man who never quite figured out what had gone wrong. I was ten years old. I didn’t know what had gone wrong, either.

A boy of ten is not without intelligence. It seems to me that then I was about as educable and perceptive as I was ever going to be in my life. What I did lack was knowledge. Was something bad happening in the world? I had no way of knowing. It was the only world I had ever experienced. I knew we moved a lot. I suspected that it was because we couldn’t pay the rent, but that wasn’t any new thing in my ten-year-old life. My father had always been a plunger. There were times when we lived in suites in luxury hotels, and times when we didn’t live anywhere at all, at least as a family. My father would be in one place, my mother in another, and me with some relative until they could get it together again. The name of the game that year was the Great Depression, but I didn’t know I was playing it. And at some point in that year of 1930 I came across a magazine named Science Wonder Stories Quarterly, with a picture of a scaly green monster on the cover. I opened it up. The irremediable virus entered my veins.

Of course it isn’t really true that there is no cure for the science-fiction addiction, because every year there are thousands of spontaneous remissions. I have wondered from time to time why it is that any number of kids can discover science fiction and some will abandon it in a year, others will keep a casual interest indefinitely but never progress beyond that, while a few, like me, will make it a way of life. I suppose both seed and soil are needed. Damon Knight says that, as children, all we science-fiction writers were toads. We didn’t get along with our peers. We had no close friends and were thus thrown on our own internal resources. Reading, particularly science fiction, filled the gaps. A more charitable explanation might be that most science-fiction readers were precocious kids who got little reward from the chatter of their subteen schoolmates and looked for more stimulating companionship in print. Either way, Damon was hooked, and so was I, and so were some ten or twenty thousand people all over the world who comprise the great collective family called “science fiction.”

I do, however, deny that I was a toad.

Actually, I was quite a good-looking ten- or twelve-year-old. I have the pictures to prove it. My reflexes were okay, and I could handle myself at sports. Never much of a ballplayer, but a good swimmer and a good marksman from the age of ten on. I did not, it is true, spend a great deal of time with my peers. I missed four years out of the beginning of my school career, partly from moving, partly from maternal stubbornness. Every time I went to school I got sick. Not just sniffles or Monday-morning fevers, but thumping good cases of all the UCD. The law said I had to go to school at a certain age, and so obediently my parents sent me off; I got whooping cough and was in bed for a month. They sent me back; I got sick again, with something else; sent me again, and I came home with scarlet fever. In the 1920s, that was no fun. It meant a Board of Health quarantine sign on the door, all my possessions baked in an oven for two hours, and nothing for me, for weeks on end, but to lie in bed and wish I had something to do. Well, I did have something to do. I read. I don’t remember a time when I couldn’t read, and the Bobbsey Twins and Peewee Harris kept me content when I couldn’t go out and skate.

After my mother came to the conclusion that the New York City public-school system was proposing to kill her only child with its diseases, she kept me out of school entirely. It helped that we moved so often. Even so, from time to time the truant officer would come around to complain. She would inform him that she herself was a fully accredited teacher, a graduate of Lehigh State Teachers College and well able to tutor her son at home. Perhaps she was. I don’t remember any lessons, only books in endless supply. But that is not a bad way of getting an education.

When I was around eight the world finally caught up with us, and I started school. They had a little trouble placing me. By age, I should have been a grade or two lower down. In terms of some of the specifics children learn, I was hardly performing at kindergarten level; when the principal asked me to write my name, I smiled sweetly a

nd said, “I’ll print it for you.” (There are no penmanship lessons in Huckleberry Finn.) But in reading and general knowledge of the world I was well up there with the big kids, and so they compromised on 4-A. It wasn’t so bad. The only thing I can find to object to in my grammar-school career was that I don’t remember learning anything in it.

My father, he was a traveling man. When he was around twenty-two he was a machinery salesman, and one of his accounts was Flegenheimer’s iron and steel works, near Allentown, Pennsylvania. There my mother, a redheaded Irish girl two or three years older than he, worked as a secretary. They got married in 1917. The next year my father was drafted. He spent a few weeks in basic training, prepping to go to France to kill off the Kaiser and finish World War I, but the Armistice came before they got around to him. He got out without ever having gone overseas. On the twenty-sixth of November in 1919 I was born. The next week my father left for the Panama Canal, where he had a job waiting. My mother and I followed, and I spent my first Christmas at sea.

They tell me that the Canal Zone was not a bad place to be—assuming, of course, that you were American, employed, and white. We had servants, including one immense black lady whose only job was taking care of me. But we didn’t stay there. My father spent his life convinced there was something better than what he had, if he could only find it. We chased it to places like Texas, New Mexico, and California over the next couple of years. By the time I was old enough to be aware of where I was, we were back in Brooklyn. And there, in one neighborhood or another, we stayed all through my childhood.

Depression or none, Brooklyn was a warm and kindly place to me. There was much to do, and little to fear. I can remember a few rough times—schoolboy fistfights, once or twice a tentative advance from some sad, predatory gay, a time or two when older kids carried a practical joke a touch too far. But nothing that made me afraid. What I remember best are pleasures. Penny candy and Saturday movie-matinees. Sunday drives to my grandparents’ home in Broad Channel, gimcrack little house that old Ernst Pohl had built with his own hands on tidal water, with killies to be seen from the plank walks that reached out to the stilted summer houses behind it. Cattail marshes you could lose yourself in, four or five blocks from my house. Summer camp at Fire Place Lodge, where I learned to ride a horse, paddle a canoe, and hit what I aimed at with a .22. Once or twice a year we would take the Lehigh Railroad to visit my mother’s family in Allentown. All I remember of them are character tags: the leap-year aunt who had had fewer birthdays than I because she was born on the twenty-ninth of February, the uncle who drank (I remember my tiny mother taking a bottle away from her six-foot-four brother and pouring it down the sink), the cousin who played the violin.

A ten-year-old is a piece of unexposed film. I soaked up all the inputs that fell on me without sharing them. I perceived quite early that I was a reader, and most of the people I came in contact with were not. It made a barrier. What they wanted to talk about were things they had eaten, touched, or done. What I wanted to talk about was what I had read.

When it developed that what I was thinking and reading was more and more science fiction, the barrier grew. I don’t want to give the impression that I read only science fiction. Perhaps I would have if I could, but there wasn’t enough of it to meet my needs. Since I had the good luck to learn to read long before I saw the inside of a school and so did not associate it with drudgery, I read quickly and easily; and if I didn’t understand all the words, I could usually get the drift, confident that sooner or later the words would fit themselves into a context. One reason for this catholicity of taste was that I had very little control over what reading matter was available to me. At ten, I had not achieved the sophistication of buying books for myself or belonging to a library; I took what turned up in the house or what I could borrow from friends. That first issue of Science Wonder was heaven, but I didn’t realize that the fact that it was a magazine implied that there would be other issues for me to find. When another science-fiction magazine came my way, a few months later, it was like Christmas. That was an old copy of the Amazing Stories Annual, provenance unknown. Given two examples, I was at last able to deduce the probability of more, and the general concept of “science-fiction magazines” became part of my life.

That Amazing Stories Annual contained the complete text of Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Master Mind of Mars, all red-skinned princesses and mad scientists and huge, four-armed, talking white apes. I doted on it. The cover enslaved me before I turned a page: bright buckeye painting of Ras Thavas, the crazy old organ transplanter of Barsoom, leaning over the sweet, dead form of a beautiful Martian maiden into which he proposed to transplant some rich old hag’s brain. I couldn’t wait to read it; having read it, at once read it again; having all but memorized it, attained the wisdom to go looking for more. I found more. I found back-number magazine stores where I could pick up 1927 Amazings and 1930 Astoundings for the nickel or dime apiece that even my ten-year-old budget could afford. I found second-hand bookstores, scads of them, which turned out to have science-fiction books: all the rest of the Burroughs oeuvre, originally published in the Grosset & Dunlap editions for a dollar and now available to me, hardly damaged, for as little as a dime. It was something of a blow to find that Burroughs had written books about other things than the planet Barsoom. I tried Tarzan as an experiment and didn’t much like it—talking great apes were not wonderful enough for me—but there were half a dozen other Mars books, plus books about Venus, Pellucidar, and the Moon. All of these interesting places appeared to have sensibly organized native civilizations, with beautiful princesses to win and important deeds of valor to do; more, they had useful and exciting inventions, like radium rifles and airships propelled by the secret rays of the sun. I got my first public-library card around then. Although I was ghettoized into the children’s section without appeal, I found tons of Jules Verne and a smattering of H. G. Wells. Verne was bread and butter, enough to survive on, at least; Wells was pure delight. And now that my antennae were sensitized, I discovered children’s books that showed the same stigmata: Carl H. Claudy, Roy Rockwood, even, although contemptibly old-fashioned and watered-down, Tom Swift.

My uncle Bill Mason turned out to be King Midas for me. He was my war-wounded uncle, gassed in the Argonne in World War I and eking out some sort of a livelihood on his disability pension, an occasional job of watch repairing, and what he could grow on a rented acre of ground in Harlem, Pennsylvania. He took me off my parents’ hands now and then in the summer, not so much to give me a vacation as to get me away from the polio scare that enlivened most pre-Salk city summers. I enjoyed going to the farm. We could swim behind the dam in the little brook, hunt ginseng in the woods, engage in butting contests with the neighbor’s bull calves. I was even allowed to fire the family shotgun now and then.

I wasn’t much use as a farmhand, but neither were my two cousins. The three of us put much more effort into the avoiding of work than into the doing of it. When trapped, we could feed the chickens and gather the eggs. We could cut a little brush and pick potato bugs off the vines. What we did as much as we could was hide.

After some research, I found the perfect hiding place in the farmhouse attic. My grandfather lived on the same farm, and he grew his own tobacco. The attic was where he cured it, so that it smelled of ripening tobacco and a sour-salty tang of heat. But that wasn’t the marvelous thing about it. The truly marvelous thing was that in a corner of the attic was a treasure-trove of old pulp magazines, hundreds of them.

Only a few were science-fiction magazines. Quite a lot were Westerns or queer things like submarine stories and sports magazines, but many were golden. Someone had been a big fan of Frank Munsey’s old Argosy, then a weekly pulp magazine selling for a dime, each issue packed with half a dozen shorts and installments of four different serials. And what serials! Borden Chase novels about sandhogs digging the Holland tunnel. Eight-parters about adventure in ancient Greece or Rome. I knew nothing of history, but I knew a go

od story when I read one, and these stories awakened my interest in the classic ages in a way that nothing in school ever did. (I have no doubt that in the long run I owe the fact that I am the Encyclopedia Britannica’s source for the Roman emperor Tiberius to those old pulp novels.) Derring-do among Soviet collective farms and in American steel mills. Medical adventures with Dr. Kildare. Exploration of every corner of the Earth. The literary style was peremptory, and someone was getting hit over the head on every page, but they were grand. And among them was the occasional pure vein of science fiction. I read A. Merritt’s The Moon Pool up in that attic, with the temperature a hundred and four under the eaves, and Ray Cummings and Otis Adelbert Kline, and I only stopped when someone dragged me away. Or when the sun went down. The house had neither electricity nor running water, and after dark there were only limited options. You could sit in the kitchen by the kerosene lantern and listen to Whisperin’ Jack Smith on the battery radio. Or you could go to bed.

So in the two years from age ten to twelve I managed to read every scrap of science fiction I knew to exist: every back issue of Amazing and Wonder and Astounding, most of Weird Tales, all the books I could find in second-hand stores, friends’ homes, and the children’s section of the library; everything. My head was popping with spaceships and winged girls and cloaks of invisibility, and I had no one to share it with.

The house we lived in when I was ten was at 2758 East 26th Street in Brooklyn.

A few months ago I did a nostalgic thing. I was driving to Kennedy Airport in my rented Avis car, about to catch a plane to Budapest and, astonishingly, with an hour or two to spare. On impulse I got off the Belt Parkway at Sheepshead Bay, hunted around, and found that very house, the first time I had seen it since I left it forty-five years earlier.