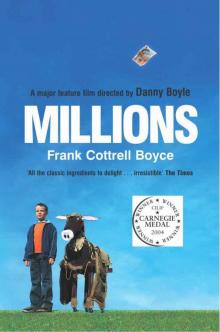

Millions

Frank Cottrell Boyce

Frank Cottrell Boyce is a screenwriter whose films include Welcome to Sarajevo, Hilary and Jackie and 24 Hour Party People. Millions is his first book.

Frank lives in Liverpool with his wife and family of seven children. He is not a millionaire and has no plans to rob a bank. However, during a short-lived career as a Punch and Judy man’s assistant, Frank earned a fortune entirely in small change. He believes this is how he first became interested in the problems created by user-unfriendly cash

Praise for MILLIONS

‘A deliciously funny story given depth by a tinge of bitter sweetness’

Guardian

‘Very funny and touching. Cottrell Boyce has a rare gift for sophisticated comedy’

FT Magazine

‘Written with charm and humour, this is a touching, absorbing oddity of a book about love, grief, avarice and generosity’

Sunday Times

‘Both funny and poignant. What, after all, is money for? Cottrell Boyce is a writer who can engage readers in such questions whilst also making them weep with laughter’

Books for Keeps

Also by Frank Cottrell Boyce

Framed

Many friends have wittingly and unwittingly helped me with this book. I’d like to thank Anand Tucker, Roger Ebert, Julian Farino, Graham Broadbent, Damian O’Donnell and my brilliant editor, Sarah Dudman.

My biggest debts, however, are to Danny Boyle – whose courageous faith in people is a miracle in itself – and to my wife, Denise, who actually is a saint.

I’d also like to thank WaterAid for making the World a better place.

For further information on WaterAid, please see www.wateraid.org

First published 2004 by Macmillan Children’s Books

First published in paperback 2005 by Macmillan Children’s Books

This electronic edition published 2008 by Macmillan Children’s Books

a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited

20 New Wharf Road, London N1 9RR

Basingstoke and Oxford

Associated companies throughout the world

www.panmacmillan.com

ISBN 978-0-330-46347-8 in Adobe Reader format

ISBN 978-0-330-46346-1 in Adobe Digital Editions format

ISBN 978-0-330-46348-5 in Mobipocket format

ISBN 978-0-330-46349-2 in Microsoft Reader format

Copyright © Frank Cottrell Boyce 2004

The right of Frank Cottrell Boyce to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Visit www.panmacmillan.com to read more about all our books and to buy them. You will also find features, author interviews and news of any author events, and you can sign up for e-newsletters so that you’re always first to hear about our new releases.

For Joe, Aidan, Chiara, Gabriella,

Benedict, Heloise and Xavier –

my gold, frankincense and myrrh

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

1

If our Anthony was telling this story, he’d start with the money. It always comes down to money, he says, so you might as well start there. He’d probably put, ‘Once upon a time there were 229,370 , little pounds sterling,’ and go on till he got to, ‘and they all lived happily ever after in a high-interest bank account.’ But he’s not telling this story. I am. Personally, I like to start with the patron saint of whatever it is. For instance, when we had to write about moving house for Literacy Hour, I put:

Moving House

by

Damian Cunningham, Year Five

We have just moved house to 7 Cromarty Close. The patron saint of moving house is St Anne (1st century). She was the Mother of Our Lady. Our Lady did not die but floated up into Heaven while still fairly young. St Anne was upset. To cheer her up, four angels picked up her house and took it to the seaside in Italy, where it can be seen to this day. You can pray to St Anne for help with moving house. She will watch over you, but not do actual removals. Anne is also the patron saint of miners, horse-riding, cabinetmakers and the city of Norwich. While alive, she performed many wonders.

The patron saint of this story is St Francis of Assisi (1181–1226 ), because it all sort of started with a robbery and the first saintish thing he ever did was a robbery. He stole some cloth from his father and gave it to the poor. There is a patron saint of actual robbers – Dismas (1st century) – but I’m not an actual robber. I was only trying to be good.

It was our first day at Great Ditton Primary. The sign outside says, ‘Great Ditton Primary – Creating Excellence for a New Community’.

‘See that?’ said Dad as he left us at the gates. ‘Good isn’t good enough here. Excellence, that’s what they’re after. My instruction for the day is, “Be excellent.” The instructions for supper I’ll leave on the fridge door.’

One thing about me is that I always really try to do whatever Dad tells me. It’s not that I think he’ll go off and leave us if we’re a problem, but why take that risk? So I was excellent first lesson. Mr Quinn was doing ‘People We Admire’ for Art. A huge boy with a freckly neck nominated Sir Alex Ferguson and listed all the trophies United had won under his stewardship. A boy called Jake said players were more important than managers and nominated Wayne Rooney for individual flair. Mr Quinn was looking around the room. To be educational about it, football was not taking him where he wanted to go. I put my hand up. He asked a girl.

‘Don’t know any footballers, sir.’

‘It doesn’t have to be a footballer.’

‘Oh. Don’t know, then, sir.’

I used my other hand to hoist my hand up higher.

‘Damian, who do you admire?’

By now, most of the others were into players versus managers.

I said, ‘St Roch, sir.’

The others stopped talking.

‘Who does he play for?’

‘No one, sir. He’s a saint.’

The others went back to football.

‘He caught the plague and hid in the woods so he wouldn’t infect anyone, and a dog came and fed him every day. Then he started to do miraculous cures and people came to see him – hundreds of people – in his hut in the woods. He was so worried about saying the wrong thing to someone that he didn’t say a word for the last ten years of his life.’

‘We could do with a few like him in this class. Thank you, Damian.’

‘He’s the patron saint of plague, cholera and skin complaints. While alive, he performed many wonders.’

‘Well, you learn something new.’

He was looking for someone else now, but I was enjoying being excellent. Catherine of Alexandria (4th century) came to mind. ‘They wanted her to marry a king, but she said she was married to Chri

st. So they tried to crush her on a big wooden wheel, but it shattered into a thousand splinters – huge sharp splinters – which flew into the crowd, killing and blinding many bystanders.’

‘That’s a bit harsh. Collateral damage, eh? Well, thank you, Damian.’

By now everyone had stopped debating players versus managers. They were all listening to me.

‘After that they chopped her head off. Which did kill her, but instead of blood, milk came spurting out of her neck. That was one of her wonders.’

‘Thank you, Damian.’

‘She’s the patron saint of nurses, fireworks, wheel-makers and the town of Dunstable (Bedfordshire). The Catherine wheel is named after her. She’s a virgin martyr. There are other great virgin martyrs. For instance, St Sexburga of Ely (670–700 ).’

Everyone started laughing. Everyone always laughs at that name. They probably laughed at it in 670–700 too.

‘Sexburga was Queen of Kent. She had four sisters, who all became saints. They were called—’

Before I could say Ethelburga and Withburga, Mr Quinn said, ‘Damian, I did say thank you.’

He actually said thank you three times. If that doesn’t make me excellent, I don’t know what does.

I was also an artistic inspiration, as nearly all the boys painted pictures of the collateral damage at the execution of St Catherine. There were a lot of fatal flying splinters and milk spurting out of necks. Jake painted Wayne Rooney, but he was the only one.

In the dining hall, a boy on Hot Dinners came and waggled his burger under my nose and said, ‘Sexyburger, sexyburger.’ All the people round the table laughed.

I found this very unenlightening and was about to say so when Anthony came and sat by me and they all stopped.

We had ham and tomato sandwiches and two small tubes of Pringles. I said, ‘I’ve been excellent. What about you?’

He whispered, ‘You are making yourself conspicuous. You need to blend in more. People are laughing at you.’

‘I don’t mind being laughed at. Persecution is good for you. They laughed at Joseph of Copertino until he learned to levitate.’

The huge boy with the freckly neck came and sat down. His belly caught the end of the table and tipped it up. My tube of Pringles rolled towards him. He picked it up and opened it.

‘They’re his,’ said Anthony, pointing at me.

‘And who are you?’ asked Freckle Neck.

‘I’m his big brother.’

‘You’re not that big. All Pringles belong to me.’ A dandruff of crumbs fell from his mouth. ‘School policy.’

‘You can’t take his Pringles. He’s got no mum.’

‘How can he have no mum? Everyone’s got a mum. Even people who’ve got no dad have got a mum. I’m enjoying these, by the way.’

‘She’s dead,’ said Anthony.

Freckle Neck stopped crunching and handed my Pringles back. He said his name was Barry.

‘Nice to meet you, Barry.’ Anthony offered him his hand to shake. Anthony believed in making friends. ‘Where do you live?’ he asked.

‘Over the bridge, next to the twenty-four hour.’

‘Now that,’ said Anthony, ‘is a very sought-after area. Very sought-after.’

My brother is very, very interested in real estate.

On the way to the playground, Anthony said, ‘Works every time. Tell them your mum’s dead and they give you stuff.’

In the afternoon, for some reason, I decided to do a St Roch. I forbore all temptation to speak during Numeracy Hour – didn’t put my hand up, didn’t answer a tables question even when pointed at. When Mr Quinn asked me if I was OK, I was tempted to reply, but I just nodded my head instead. I wasn’t contributing to the class, but I was being excellent in a different, less obvious way.

I kept this up all the way home. Dad had left instructions fixed to the fridge door with a Clangers magnet:

Dear Boys

Chicken and asparagus pie. The pie is in the top drawer of the freezer. Put the oven on to 190º. Go and watch Countdown. When Countdown is over, the oven will be warm enough. Put the pie in. Take your uniforms off and put them over the end of your bed. Put your tracksuits on. Then put some oven chips in. I will be home before they’re cooked.

D

I enjoyed being called dear.

When Dad came home, we had the pie, followed by five pieces of fruit and a pint of water each to hydrate our livers. When they were completely hydrated, we did our homework and he sat with us. I still didn’t say a word, but then the phone rang and I accidentally answered it. I don’t know how St Roch kept it up for ten years, although admittedly he had it easier living in a time before phones. Anyway, it was Mr Quinn. My teacher actually rang our actual house. How excellent is that!

Later Dad came and sat on the end of the bed and said, ‘You’re a bit quiet today. Cat got your tongue?’

I shook my head.

‘I heard you were quiet in school too.’

I nodded.

‘Anything you want to tell me?’

Shook again.

‘Right. Well, time for bed.’

He’d nearly closed the door when the temptation to speak finally overwhelmed me. I said, ‘What did Mr Quinn want?’

‘Well you know, a chat really. It was him who was telling me about how quiet you were.’

‘He said thank you to me three times, so I must have been fairly excellent. Did he say I was excellent?’

‘He said . . . Yes, he said you were excellent.’ He ruffled my hair. ‘One of the customers was telling me about this place today. It’s called the Snowdrome. You can toboggan or have a go at skiing. Fancy it?’

I wasn’t sure.

‘For being excellent. As a reward.’

‘OK, then.’

‘OK. So we’ll go straight from school tomorrow, because you’re excellent.’

The Snowdrome was quality completely. It’s real snow inside, made of ice crystals from a big blower. They give you a special snowsuit to wear when you’re in there. You’re not supposed to have two people on a toboggan, but Anthony explained to the man that our mum was dead and he let us do what we liked. We went down twice two together, once on our bellies and three times backwards.

In school next morning, everyone was interested to hear all about it. I explained how the ice blower worked and was giving a demonstration of backward-tobogganing when I smashed into Mr Quinn, who was coming in through the door.

‘Watch it! Watch it!’ he yelled as he dropped all our workbooks.

I helped him pick them up. I saw my own, the one about St Anne. It had a note stuck inside, which he took out and pocketed as he gave me back the book.

‘What d’you think you’re playing at, lad?’

‘The Snowdrome, sir. We went. It was good.’

He suddenly looked all cheery. He said, ‘Well, you could write about that for today’s Literacy Hour, couldn’t you? Give an exciting description of all the fun you had. No patron saint of Snowdromes, I bet.’

Speke Snowdrome

by

Damian Cunningham, Mr Quinn’s Class

Speke Snowdrome is quality. You can skate or toboggan. The patron saint of skating is Lidwina (virgin martyr, 1380–1433), who was injured in a skating accident and spent the rest of her life in bed. She bore her mortification with forbearance and performed several wonders: for instance, eating nothing but Holy Communion wafers for seven years. You can read more about her at www.totallysaints.com/lidwina.html

The truth is, there is always a patron saint. As St Clare of Assisi (1194 –1253) once said to me, ‘Saints are like television. They’re everywhere. But you need an aerial.’

2

Anthony can’t believe I’ve got this far without mentioning European Monetary Union.

European Monetary Union

by

Anthony Cunningham, Year Six

Money was invented in China in 1100 BC. Before that Chinese merchants used knives and spades to trade

with. These were too heavy to carry, so they used model knives and spades instead. These were made of bronze and were the first coins. Soon every country had its own coins. In Europe alone there were the sturdy German Deutschmark, the extravagant Italian lire, the stylish French franc and of course the Great British pound. The pound was first invented in 1489, when it was called a sovereign. On 17 December it will be replaced by the euro.

When you put an old pound in the bank, they put it on a special train that takes it to a secret location to be scrapped. Then the train comes back in the morning with new money. So right now nearly all the money in England is on trains.

You should collect your old coins in separate jam jars – one for five pees, one for tens, one for twenties and so on. When they’re full, take them to the bank to exchange. 17 December is ‘€ Day’, the day we say GOODBYE to the old pound.

Anthony said goodbye to the old pound nearly every day. On the way home from school, he used to run like mad to the middle of the footbridge, then wait there till a train went roaring by beneath us. Then he’d wave and yell until it was out of sight, just like the Railway Children, shouting, ‘Goodbye! Goodbye, old pounds!’

He made it sound like every single ten-pound note was a personal friend. Sometimes you’d think he was going to cry. ‘Just think,’ he’d say, ‘500-odd years of history, up in smoke.’

Other times, he’d seem quite happy about it. ‘Just think,’ he’d say, ‘come Christmas we’ll be able to spend the same money from Galway to Greece.’

Every night before we went to bed, the three of us dropped any small coins we had into a big whisky bottle at the foot of the stairs. On the way to bed, Anthony would nearly weep as he dropped his five pees in. On the way to breakfast, he’d stroke the bottle happily and say, ‘Amazing how fast it mounts up.’

Personally, I think, so what? Money’s just a thing and things change. That’s what I’ve found. One minute something’s really there, right next to you, and you can cuddle up to it. The next it just melts away, like a Malteser.