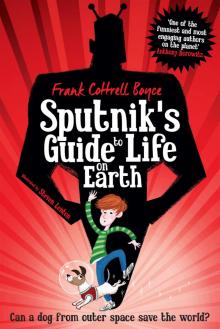

Sputnik's Guide to Life on Earth

Frank Cottrell Boyce

For Keziah and Samuel – the beloved children of Christiana Eke Adah

Contents

1. Spicy Chicken Wings

2. 28 June – Annabel’s Birthday

3. Lightsabers

4. Mooring Hitch Knots

5. Laika

6. The Companion

7. 1kg Plain Flour, 1 Tub Margarine, 500g Mushrooms

8. Milk

9. Chicken-and-Mushroom Pie

10. Spanish Lessons

11. Eggs

12. Concealer

13. Post-It Notes

14. 31 July – St Peter’s Summer Treat

15. TV Remote Control

16. Curtains

17. Jailbreak

18. Geese

19. Be Nice

20. Spaghetti

21. Fire Drill

22. Shangri-La

23. Stairlift

24. Teeth

25. Grandad’s Harmonica

26. Postcards

27. The Sea Chest

Author Note

About the Author

About the Illustrator

Before you start anything, make a list. That’s what my grandad says. If you’re making a cake, make a list. If you’re moving house, make a list. If you’re running away to sea, make a list.

At least, that’s what he used to say. Nowadays who knows what he’s going to say? Sometimes he looks in the mirror and says, ‘Who’s a bonnie boy then, eh?’ Sometimes he looks in the mirror and shouts, ‘Who’s this old bod in my mirror?! What’s he doing in my bedroom?’

Sometimes he comes into the kitchen and says, ‘Tickets, please!’

And it’s no good saying, ‘Grandad, you’re not on a ship any more. This is the kitchen. I don’t need a ticket,’ because that just gets him going.

If he asks for a ticket, I just look in my pocket for a piece of paper, hand it over and wait to see what he does.

Usually it’s ‘That seems to be in order. Take a seat and enjoy your voyage’. Then he gives you a little salute and you salute him back.

Sometimes it’s ‘This is a second-class ticket, not valid in this part of the ship’. Then I have to go out into the sitting room, wait a bit and come back in again.

Today was a ‘Tickets, please!’ day, so I handed him the red notebook I was holding, open as though it was my passport. I said, ‘I think you’ll find this is in order.’

1. Spicy Chicken Wings

2. 28 June – Annabel’s Birthday

3. Lightsabers

4. Mooring Hitch Knots

5. Laika

6. The Companion

7. 1kg Plain Flour, 1 Tub Margarine, 500g Mushrooms

8. Milk

9. Chicken-and-Mushroom Pie

10. Spanish Lessons

11. Eggs

12. Concealer

13. Post-It Notes

14. 31 July – St Peter’s Summer Treat

15. TV Remote Control

16. Curtains

17. Jailbreak

18. Geese

19. Be Nice

20. Spaghetti

21. Fire Drill

22. Shangri-La

23. Stairlift

24. Teeth

25. Grandad’s Harmonica

26. Postcards

27. The Sea Chest

He gave it the hard stare.

Then he gave me the hard stare.

‘I know a list when I see one,’ he said, ‘and this –’ he shoved it back into my hand – ‘is just a shopping list. Mostly.’

‘Now that,’ I said, ‘is where you’re wrong. ‘This is a list of all the startling things that happened this summer.’

‘What happened this summer?’

‘Read it and see. I probably shouldn’t have written it all down. It might get me into trouble. We broke a lot of laws, including some of the laws of physics. But I wrote everything down anyway because I didn’t want to forget any of it.’

1.

Spicy Chicken Wings

I don’t know why I answered the door.

It wasn’t even my own door.

By then I was staying at the Children’s Temporary Accommodation, but in the summer they put you with a family. They put me on a farm called Stramoddie with a family called the Blythes. It’s right down near Knockbrex.

When Mrs Rowland from the Temporary dropped me off, she said, ‘This is Prez. He’s a good boy but he doesn’t talk much. He’s very helpful, but perhaps best not to let him near your kitchen knives.’

‘When you say he doesn’t talk . . .’

‘Hasn’t said a word in months.’

‘Just exactly what we need,’ said the dad. ‘Someone to balance out our Jessie. Jessie does enough talking for ten families.’

That’s one good thing about not talking, by the way – you don’t have to work out what to call the mum and dad. You can’t call them Mum and Dad, because they’re not your mum or your dad. Calling them Mr and Mrs Whatever would be weird. And calling them by their first names is even weirder.

‘Even if you did want to speak, Prez, you wouldn’t get a word in. This is the House of Blether.’

He was not joking. Mostly they talk so much and so loud, you can’t tell who’s saying what. Though mostly it’s Jessie.

‘I hate sitting here.’

‘No phones at the dinner table!’

Then they all drop their heads and say a prayer very quietly. But the second they’ve said amen, they all start shouting again.

Folk think that if you’re not talking you’re not listening. But that’s not true. For instance, I was the only one who heard the doorbell the night that Sputnik came.

It was a Wednesday. Tea was spicy chicken wings, salad and baked potatoes. We’d finished eating and everyone was clearing up in the kitchen.

The doorbell rang.

The family didn’t hear it because they were all shouting.

‘Why is

everyone shouting?’

‘The radio’s too loud.

We have to shout to be heard.’

‘No. The radio is loud so

I can hear it over the shouting.

If there wasn’t shouting,

the radio would be quiet.’

The doorbell rang again.

I never answer doors, because answering doors means you have to speak to someone, sometimes a stranger even.

The doorbell rang again.

Then I thought, What if it’s my grandad?!

I used to live with my grandad, but he got into a wee spot of bother and had to be taken away. That’s how I ended up in the Children’s Temporary. They said that if Grandad could get himself sorted out, he would be allowed to come back and I could go and live with him again.

Maybe this was Grandad – all sorted out and coming to take me back to the flat in Traquair Gardens.

Maybe I was going home.

So I answered the door.

But it wasn’t Grandad. It was Sputnik.

I have to describe him because there’s a lot of disagreement about what he looks like:

Height and age – about the same as me.

Clothes – unusual. For instance: slightly-too-big jumper, kilt, leather helmet like the ones pilots wear in war movies, with massive goggles.

Weapons – a massive pair of scissors stuffed into his belt like a sword. There were other weapons but I didn’t know about them then or I definitely wouldn’t have let him in.

Luggage – a big yellow backpack. I now know he more or less never takes that backpack off.

Name – Sputnik, though that’s not what he said to start with.

Manners – not good. My grandad always says tha

t good manners are important. ‘Good manners tell you what to do when you don’t know what to do,’ he says. Sputnik put his hand out to me, so I shook it. That’s good manners. But Sputnik did not shake back. Instead Sputnik grabbed my hand with both of his and swung himself in through the door, using my arms like a rope.

‘Mellows?’ he said.

Mellows is my second name. So I thought, This must be someone from the Temporary coming to take me back. Maybe Grandad had got himself sorted out. Maybe the family have complained about me.

‘I too . . .’ he said, pushing his goggles up on to the top of his head, ‘am the Mellows.’ He thumped his chest. It sounded like a drum.

Oh. We had the same name.

‘The same name!’ He flung his arms around me. I don’t know much about hugs, but if a hug is so fierce it makes you worry that your lungs might pop out through your nostrils, that’s a big hug.

I didn’t know what to do. The Blythes were noisy, but I was pretty sure they’d notice if I let a stranger in goggles and a kilt into their front room. They seemed easy-going enough, but it had to be against the rules just to let any old stranger walk into the house.

‘Stranger!’ he said, as though he had heard what I was thinking. ‘Stranger! Where’s the stranger?! We have the same name. We. Are. Family!’

He strolled right past me, pulling his goggles back down.

The mum was in the living room about to turn the TV on, with her back to the door. Mellows put his hands on his hips and yelled, ‘I. Am. Starving! Take me to your larder!’ The mum spun round, dropped the remote, stared at him, then stared at me. I thought she was going to scream. But she didn’t.

She smiled the biggest smile I’d ever seen her smile and she said, ‘Ooohhhh, aren’t you lovely?!’

‘Yes,’ said Mellows, ‘I am lovely. Let the loveliness begin for the lovely one is here!’ Then he actually sang, ‘Here comes the Mellows!’ to the tune of The Beatles’ ‘Here Comes the Sun’.

The mum looked at me and said, ‘Is he lost?’ She didn’t wait for me to answer. ‘Everyone, come and see!’ The entire family avalanched into the living room.

‘Amazing!’ yelled Jessie. ‘Did Dad bring him?’

‘No. Prez did.’

‘Prez? Really?’

‘Nice one, Prez.’

Maybe I’d done the right thing.

Mellows strode over and shook Jessie’s hand.

Jessie shouted, ‘Whoa! Did you see that? He shook hands with me!’ She seemed to think shaking hands was a rare and unusual thing, like walking on water or having hair made of snakes.

Annabel waddled past Jessie, saying, ‘Me now, me now.’ She shook hands with him and they all clapped.

Don’t get me wrong. When Mrs Rowland brought me down to Stramoddie, they were all really nice to me. The food was way better than in the Temporary, Ray let me have the top bunk, they gave me my own pair of wellies for walking around the farm, but nobody actually clapped. There was no fighting over whose turn it was to shake hands with me! And no one did what Jessie did to Mellows. She called him a ‘bonnie wee man’ and she rubbed noses with him!

The mum asked him if he was hungry.

‘Got it in one!’ roared Mellows. ‘That’s why I said, “Take me to your larder!” Do it now before I starve to death before your very eyes!’

He flung himself on to the floor as though he was dying there and then. The mum ran into the kitchen and came back with the leftover spicy chicken wings. If you’re going to eat food, it’s good manners to get a plate and a knife and fork and sit down. Unless it’s chips. You can eat chips in the park. But the mum did not give Mellows a knife and fork or a plate or a place at the table. No. She held a spicy chicken wing up in the air. Mellows looked up at it. Then she dropped the chicken right into his mouth. He chewed and sucked at it, then pulled the clean bones out of his mouth.

Not good manners.

I think if I’d done that people would have complained. When Mellows did it, they didn’t complain. They clapped again.

The mum said he was a clever boy!

‘No doubt about that,’ said Mellows. ‘I am a clever boy. I’m a chuffing genius if the truth be told.’

When the dad came in and saw Mellows sprawled on the couch, Jessie said, ‘Can he stay? Can he stay? Please can he stay?’

‘I suppose so,’ said the dad with a big sigh. ‘But just for tonight.’

‘Shake hands with him!’

The dad shook hands with Mellows and asked him his name. Then he asked him his name again, like, ‘What’s his name? What’s his name? What’s his name?’

Mellows pleaded with me to make him stop. ‘Please tell this joker my name before he shakes my hand off!’

Before I could stop myself I said, ‘Mellows,’ out loud.

Everyone stared at me.

‘Yes! I am Mellows,’ said Mellows. He pointed at me. ‘Two merits for listening skills.’

No one looked at Mellows. They were all still staring at me.

‘Mellows?’ said the mum. ‘Like you, Prez? That’s lovely. Well done, Prez.’

I knew she meant, Well done for talking.

Until the night Sputnik came, I used to lie on the top bunk in Ray’s room every night, looking at the ceiling and worrying about Grandad. When Grandad used to go off on his big long walks, for instance, I always went after him to make sure he didn’t get lost. Who would go after him now? Maybe he wasn’t even allowed to go off any more? Maybe they locked him in?

But after Sputnik came I didn’t have time to think about anything but Sputnik. That first night, for instance, I was thinking . . . Sputnik rang the doorbell. But there is no front doorbell at Stramoddie.

2.

28 June – Annabel’s Birthday

One thing that made me feel good when I came to Stramoddie was the lists. They put lists everywhere. They had a shopping list on the fridge door.

A ‘Whose Turn It Is To Do What’ list on the kitchen noticeboard.

Post-it notes about food on the kitchen table.

A whiteboard with ‘Every Single Morning’ written on it:

Empty dishwasher

Feed chickens

Turn out ponies

Check gates

Switch on cow crossing

It had a Sharpie stuck to it so you could put a tick next to each thing when you’d done it.

Grandad used to be a cook on a ship. ‘I’ve cooked for kings and criminals on all the Seven Seas,’ he liked to say. ‘One thing I know is, life is like cooking. Before you start, make a list. That way you know where you’re up to.’ He also says, ‘Make yourself useful. Life is like a kitchen. If you stand around doing nothing, someone is bound to spill something hot on you.’

Those first days, I didn’t know how to make myself useful with chickens or ponies. But I did know how to empty a dishwasher so I did that every morning. And checking the calendar reminded me of being back at Traquair Gardens with Grandad, so I did that every morning too. That’s how I knew that the day after Sputnik arrived was Annabel’s fifth birthday.

Annabel’s Party List

Friends arrive

Musical Bumps/Statues

Pass the Parcel

Musical Chairs

Presents

Food

Playing Out

Cake

Presents. I didn’t want to be the only one not giving her a present. The nearest shops to Stramoddie are about a million miles away, at Kirkcudbright. I thought I could make her a card and maybe find something in my backpack that I could wrap up for her. I just needed some paper and scissors.

The others were putting up a ‘Happy Birthday’ banner in the kitchen and laying out bowls of snacks. The only one who wasn’t helping was Mellows. He was sprawled on the couch with his hands behind his head. I noticed the scissors in his belt.

‘Want to borrow them?’ he said.

– That would be good.

‘No problem.’ Without even looking at me, he s

wiped the scissors out of his belt and flung them across the room. They flashed through the air and stuck, shivering, deep in the wood of the door, right next to my head.

I held my breath.

‘I never miss.’ He grinned. ‘Unless I mean to. What are you going to give her?’

– I’m not sure yet.

‘Food. Everyone loves food. Just give her food.’

– She has loads of food. They’re laying it out in the kitchen. There’s a bowl of Hula Hoops in there you could swim in.

‘Let’s go! Let’s swim!’

– No. I’ve got to go and get her a present.

He followed me up to Ray’s bedroom. I keep everything in my backpack. I never unpack. I emptied all my stuff on to the bed to see if I had anything that would make a good present for little Annabel.

‘You know,’ said Mellows, looking out of the window, ‘this is an excellent little planet. You’re crazy to think of running away.’

– How do you know I’m thinking of running away?

‘Your bag is packed. Including your toothbrush. You might as well be wearing an “I’m Thinking of Running Away from Home” T-shirt.’

– But this isn’t my home. I’m just a visitor. If I ran away, I’d be running back home. I keep my bag packed in case something goes wrong and I get sent back to the Children’s Temporary. Hang on – this is like we’re having a conversation. But I’m not talking.

‘I’m reading your mind. If you won’t speak, you leave me no choice but to read your mind.’

– You can read minds?

‘I can do things you haven’t dreamed of. Can’t you feel me in your mind? Like someone tickling the inside of your skull with a toothbrush?’

– That’s exactly what it feels like. Stop it.

‘Oh, but I’m having such a nice time inside your head. How about these? I bet little Annabel would love these!’

– Those are my underpants.

‘Sorry. Such bright colours. Thought they were some kind of tortilla. Are you sure they’re not edible?’

– They’re definitely not edible.

‘What about this?’

– That’s the chopping knife my grandad gave me. It’s really sharp. It’s exactly the same as his. No one’s supposed to know I’ve got it. Give it back.