Rebecca's Promise

Frances R. Sterrett

Produced by Annie R. McGuire. This book was produced fromscanned images of public domain material from the GooglePrint archive.

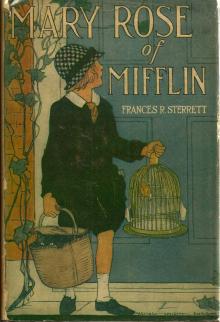

Book Cover]

REBECCA'S PROMISE

By Frances R. Sterrett

Rebecca's Promise Jimmie the Sixth William and Williamina Mary Rose of Mifflin Up the Road with Sallie The Jam Girl

* * * * *

D. APPLETON AND COMPANYPublishers New York

SHE THRUST THE VIOLETS INTO REBECCA'S HAND [page 4]]

REBECCA'SPROMISE

BYFRANCES R. STERRETT

AUTHOR OF "JIMMIE THE SIXTH," "MARY ROSE OF MIFFLIN,""THE JAM GIRL," ETC.

ILLUSTRATED BYE. C. CASWELL

D. APPLETON AND COMPANYNEW YORK LONDON1919

COPYRIGHT, 1919, BYD. APPLETON AND COMPANY

TOLILIAN JOSEPHA STERRETT

who believes in memory insurancefor you and for me.

ILLUSTRATIONS

FACING PAGE She thrust the violets into Rebecca's hand _Frontispiece_ "Do you mean to tell us that we can't go?" 152 "Hello, Kitty!" 302 "I love you, Rebecca Mary" 324

CHAPTER I

"I never should have brought you here," murmured Cousin Susan Wentworth,as she looked across the table at young Cousin Rebecca Mary Wyman, whosat on the other side of the white cloth like a small gray mouse withbright expectant eyes, a pretty pink flush on her cheeks and her headwith its crown of soft yellow brown hair held high. "I should have savedmy money for new kitchen curtains. The curtains in my kitchen are adisgrace to any housekeeper. But life wouldn't be worth much if wedidn't occasionally do something we shouldn't, would it?" And she smiledat pink-cheeked Rebecca Mary. "The memory of this pretty room with thegay crowds of people, the music, the good things to eat will last longerthan any curtains. And I can cut down the old bedroom curtains for thekitchen. Rebecca Mary, did you ever think that is what life really is,cutting down our desires to fit our necessities?"

Rebecca Mary sniffed. She had known that for twenty-two years. She didnot have to be thirty-nine like Cousin Susan to learn that necessitiesalways crowd out desires. And anyway she did not wish to talk ofnecessities, they were stupid and uninteresting, when for once in herlife she was a part of what no one in the wide world could ever considera necessity.

She let Cousin Susan study the card the attentive waiter handed to her,and while Cousin Susan tried to keep her mind from prices and on names,Rebecca Mary's bright eyes roved over the big brilliant room. She hadnever expected to enter it. She had scarcely believed her two pink earswhen they told her that Cousin Susan had said, quite casually, "RebeccaMary, suppose we go to the Waloo for tea?" Rebecca Mary had given astartled gasp, but here she was at the Waloo trying to forget that herold blue serge suit was wide where it should be narrow and narrow whereit should be wide, and that her hat had only been given a good brushingto make it ready for another season.

Afternoon tea was served at the Waloo in the Viking room, a beautifulplace with its scenes from the old Norse sagas on the walls above awainscoting of dark wood and with lights like old ship lanterns hangingfrom the beamed ceiling. The chairs and tables were suggestive of longago days, also, but the linen, the silver, the dainty china, the musicand the guests were very much of to-day.

Rebecca Mary watched the young people almost enviously as Cousin Susanhesitated over _foie gras_ sandwiches, which were expensive andtherefore suitable for an occasion which was to cost her kitchen its newcurtains, and lettuce sandwiches which were cheap and which she madeherself every time the Mifflin Fortnightly Club met with her. RebeccaMary could easily imagine what joy it would be to come to the Vikingroom in smart new clothes and with a young man like--like that tallyoung fellow who was with the girl in the wistaria taffeta. It made thepink in Rebecca Mary's cheeks turn to rose just to think of what joythat would be.

There were any number of girls in the Viking room with whom Rebecca Marywould have changed places in the twinkling of an eye. It hurt almost asmuch as an ulcerated tooth to watch those radiant young people. And whenyou have an ulcerated tooth you don't, unless you are strong-minded orphilosophical or stoical, laugh and chatter gayly; you know you don't.Rebecca Mary wasn't strong-minded nor philosophical nor stoical, she wasjust a girl who had never had anything and, oh, how she did wantsomething, and she wanted it right away. That was why her eyebrowsfrowned yellow-brownly, and the corners of her mouth drooped a bit.

"Oh, Cousin Susan!" she groaned, "why did we ever come here? Why didn'tyou take me to Childs'?"

"Eh?" murmured Cousin Susan, still hovering between expense andcuriosity.

But before she could say another word a little girl ran up to them, anelflike little thing, who held a huge bunch of violets in her hand. Shehad been following a man from the room when she had seen Rebecca Maryand dashed around the tables, just missing a disastrous collision with afat waiter, to arrive breathless beside her.

"Oh, Miss Wyman!" she whispered, her small face aglow with importance."I'm so glad I saw you. This is my birthday, and my daddy brought mehere for tea just as if I were all grown up. He bought me these violets,too, and I've had them all afternoon so I'd like to give them to you nowbecause," her face grew crimson, and her voice rang out above the hum ofvoices, "I love you!" She thrust the violets into Rebecca Mary's handand ran away without giving Rebecca Mary a chance to say one word.

Rebecca Mary just saw a portion of her father's back as he disappearedthrough the door, and she looked down at the violets with an odd flashin her gray eyes. No one ever had given her violets before. She hadalways picked them herself on the sunny slope of the bluff at Mifflin.

"What a dear child," smiled Cousin Susan. "Who is she?"

"One of my pupils, Joan Befort. Yes, she is a dear." Rebecca Mary buriedher hot cheeks in the cool fragrance of the violets for a moment.

When she lifted her head she met the amused glance of an elderly womanat the next table. She must be a grandmother woman, Rebecca Mary thoughtswiftly, although she did not look like any grandmother Rebecca Maryknew with her smart and expensive hat and blue gown, on the front ofwhich was pinned a bunch of violets and an orchid encircled withfoliage. The smile which lurked around the lips of this mostungrandmotherly looking grandmother made Rebecca Mary remember littleJoan Befort's fervent declaration of affection, and she smiled, too. Howfunny it must have sounded in the crowded tea room. "I love you!"Rebecca Mary giggled, she couldn't help it, even if she was mostdreadfully embarrassed.

At the table beside the ungrandmotherly looking grandmother was a youngman the very sight of whom sent Rebecca Mary into a quiver of delight.She had seen his picture in the Gazette too many times not to recognizehim. He was young Peter Simmons, who had left college in his sophomoreyear to drive an ambulance in France during the second year of the greatwar. He had been awarded a _croix de guerre_ for "unusual bravery underfire," and later had gone into the French flying service until he couldfight under his own flag. He had been with the American Army ofOccupation in Germany and had only recently returned to Waloo. No wonderRebecca Mary thrilled all down her back bone as she realized that shewas looking at a hero. She stared and stared for she might never see oneagain, and the hero raised his eyes and saw awed admiration written inhuge letters all over her flushed face.

Evidently young Peter Simmons did not care for awed admiration, perhapshe had had too much of it, perhaps it made him unpleasantlyself-conscious, for he scowled blackly and murmured an impatientsomething to the grandmother which made her look at Rebecca Mary again.Reb

ecca Mary turned a deep crimson and was horribly uncomfortable. Sheknew very well what they were saying, that such a shabby girl had nobusiness among the fine birds in the Viking room, and she scowled, too.She could give scowl for scowl as well as any one. Peter's black frownmade you laugh, but there was something rather pathetic about RebeccaMary's bent yellow-brown brows, perhaps it was because her lower lipquivered as she hastily averted her shamed eyes.

On the other side of young Peter was a girl no older than Rebecca Mary,and she was so prettily and smartly clothed that she made Rebecca Maryfeel like Cousin Susan's kitchen curtains, old and ragged. But every onein the room made her feel like that, she thought miserably, and shetossed her head higher to show how little she cared as her glance roamedon to the man on the other side of the grandmother. Of course thegrandmother must be old Mrs. Peter Simmons, and old Mrs. Peter Simmonswas one of the most important women in Waloo, so important that a poorlittle school teacher like Rebecca Mary could never hope to know her.Rebecca Mary rather liked the face of the man on the other side of Mrs.Peter Simmons. He was older than young Peter, and the most doting friendcould not have called him handsome, but he had something much betterthan perfect features. He was the type of man who would do things, shedecided, and then she saw Mrs. Simmons turn to speak to him and with alittle shrinking feeling of horror Rebecca Mary knew that they weretalking of her, for the man who could do things raised his head andlooked directly at her. For a moment their eyes met. Rebecca Mary wasfurious to feel her cheeks burn and her heart thump. She scowled beforeshe turned her head quickly. She wouldn't look at that table again. Ishould say not!

There were other tables and other family parties, and, oh, dear! othercouples. Old Samuel Johnson knew exactly what he was talking about whenhe said that "envy is almost the only vice which is practicable at alltimes and in every place." Rebecca Mary did find it so very very easy tobe envious. About the only person she did not envy that afternoon was ashort, stout, middle-aged man with a red face, who sat at a table byhimself and consumed vast quantities of hot buttered toast.

Rebecca Mary had never imagined there were so many gay, light-heartedpeople in the world as there were in the Viking room that May afternoonand more would have entered if it had not been for the silken barrierwhich was held in front of the door by two very haughty waiters. RebeccaMary felt blue and depressed to the very toes of her common-senselittle shoes. She felt so hopelessly out of the gay and brilliantpicture. She almost wished that Cousin Susan had not asked her to theWaloo for tea.

"Which shall we have, Rebecca Mary?" Cousin Susan found herself quiteincapable of making such a momentous decision without assistance."Lettuce or _foie gras_."

Rebecca Mary did not hesitate a second. She knew. "_Foie gras_," shesaid promptly. "I've never tasted them, and I've made hundreds oflettuce sandwiches, just thousands of them. What is the use of going tonew places if you don't try new things?" There was just a trace ofimpatience in her low voice as if she thought that Cousin Susan shouldhave known that without being told.

"H-m," murmured Cousin Susan. "The _foie gras_, then. They certainlysound mysterious and adventurous." And having given her order, CousinSusan looked about her. "Isn't this an attractive place? I've read inthe Gazette about the afternoon teas in the Viking room and how popularthey were. I suppose all these people are very rich and important. Noneof them will pay for tea with kitchen curtains." And Cousin Susan's eyestwinkled.

Rebecca Mary's eyes twinkled, too, although really there was nothingvery amusing to her in paying for tea with ten yards of any kind ofmaterial. It was rather sordid to her and poor and generally horrid,like her very existence.

Cousin Susan looked at her frowning little face and fingered the silverin front of her with hands which although well cared for showed thatthey were more for use than ornament. Cousin Susan's hands exactlyillustrated Cousin Susan's heart, which was so big and generous andhelpful that the hands were often overworked. As she looked at RebeccaMary Cousin Susan took a sudden determination and followed an impulse,which was nothing new for her, and which sometimes brought her greatsatisfaction and sometimes nothing but dissatisfaction.

"Don't frown like that, Rebecca Mary," she commanded like a generalspeaking to a very small private. "It is a lot easier to put a wrinklein your forehead than it is to get one out as you'll learn some day. Andwhile we are on the subject of your looks I'm going to take an oldcousin's privilege and tell you what I think of you. It's a shame to doit here," she acknowledged ruefully, "but if I take the six-twenty trainI shan't have another chance. You know," she went on in a firm lowvoice, "I don't like the way you live, and your mother wouldn't like itif she knew. Why, you don't get a thing out of your life, Rebecca Mary,not a thing!"

"I don't see what I can do," murmured Rebecca Mary with a twist of hershoulders and a rebellious flash in her gray eyes. "You needn't think Ilike my life, Cousin Susan. It isn't one I should ever choose. I shouldsay not! But I try to make the best of it."

"But you don't make the best of it. That is just the point. You makesuch a horrid worst of it. Yes, you do!" as Rebecca Mary indignantlydeclared that she didn't. "Listen. I've watched you and I never imagineda girl could detach herself from life, real life, as you have done. Youhaven't any friends, you don't go anywhere but to school, you don't doanything but teach the third grade in the Lincoln school."

At that Rebecca Mary did interrupt and there was a bright red spot oneach of her cheeks, like a poppy in a bed of lilies. "It costs money tohave a share in real life," she said in a suppressed voice which madeyou think how very thin the crust of earth around a volcano must be."And I haven't any money. You know how awfully little we have and howmuch it costs to live now. I have to send something home every month andthere are always taxes and insurance. And I have to provide for my oldage! You have no idea what a nightmare that is," tragically. "I wake upin the night thinking what will happen when I'm too old to teach.It's--it's ghastly!" It was so ghastly that she shivered, and thepoppies left her face so that it was just a field of white lilies.

"You are thinking entirely too much of your old age. You are robbingyour youth for it. It is perfectly ridiculous for you to make such anightmare of the future. I know it isn't entirely your fault. Yourmother is rabid on the subject. She has brought you and Grace up tothink of old age as a blood-thirsty old beast who has to be fed withyouth. Yes, I know all about your Aunt Agnes and your second CousinLucy. But, my dear, they could have saved and saved and their moneymight have been lost just when they needed it. You can't be sure ofkeeping money no matter how you save it. That's why I spend mine." Shelooked at the dainty expensive sandwiches the waiter placed before herand laughed. "It's gospel truth, my dear," she went on soberly, "thatthe only thing you can be sure of taking into the future is what you canremember, the memory of the good times you have had, the people you havemet, the places you have seen, the books you have read, the music youhave heard. Don't you know that youth should enjoy things for old ageto remember? And take it from me, Rebecca Mary, that the old find theirgreatest pleasure in recalling their youth. Will you have cream or lemonin your tea? Lemon always seems more like a party to me."

Rebecca Mary took the lemon while a puzzled frown appeared between hertwo eyebrows. "It isn't that I don't like my work, Cousin Susan," shesaid slowly, "for I do. I love children, and I love to teach. If I had amillion I should want to teach somewhere, in a settlement or a mission,you know. But I'll admit that the future does scare me blue. Suppose Ishould be ill, suppose----"

"Suppose fiddlesticks!" Cousin Susan broke in impatiently.

"It's all very well for you to talk. You have some one to take care ofyou, a husband, and----"

"My dear, you can't guarantee a husband any more than you can a savingsaccount. Women are left penniless widows every day. Don't misunderstandme, Rebecca Mary. I believe in a certain amount of saving, but I don'tbelieve in sacrificing everything in the present to a future you maynever have. How do you know you will live to grow old? How do you kn

owthat a grateful pupil won't leave you an income?--that has happened ifyou can believe the newspapers. How do you know that you won't makeyour own fortune in some marvelous way? That's the loveliest part oflife, Rebecca Mary. You don't know what is waiting for you around thecorner so you might as well expect riches as poverty; better in myopinion. I'd always rather look forward to a fried chicken than a soupbone hashed."

Rebecca Mary had to giggle when Cousin Susan suggested that a gratefulpupil might leave her an income. That was even more improbable than thatshe would make a fortune for herself.

"Cousin Susan," she giggled scornfully, "You are a perfect silly!"

"That may be," admitted Cousin Susan, "but I'm telling you good solidsense. A proper amount of pleasure is as necessary to the realdevelopment of human beings as bread or boots. Every one admits thatnow. And you're not getting a proper amount, my dear. You aren't gettingany! Why, you aren't living, you only breathe, and life is more thanbreathing. You are naturally impulsive. Can't you let yourself enjoylife instead of fear it? Yes, you are afraid of it. I've watched you.And from what you say I imagine that your room-mate was just anotherlike you. I'm glad she has gone home. And your clothes are a scandal.How many years have you worn that suit?"

Rebecca Mary's face turned a bright crimson to match the red-hotindignation inside of her. How dared Cousin Susan talk to her like that?She was doing the best she could. She shouldn't tell Cousin Susan howold her blue serge was. It was none of Cousin Susan's business.

"You wouldn't feel so shut out of the world if you looked like otherpeople and went where other people go. I don't suppose you speak anunprofessional word all day," went on Cousin Susan with growingindignation at what she considered the waste of a perfectly good girl."It's a crime, Rebecca Mary Wyman! A crime! And you needn't boast aboutyour old age provision when you haven't the brains to make a sensibleone. I'm as poor as a church mouse myself. Your Cousin Howard will nevermake more than a decent living, and we have two children to feed andclothe and educate. I hadn't any more business to come here for tea thanI would have to go to the Zoo and buy a baboon for a parlor ornament.But if I don't do something occasionally to make a day stand out,something that it is a pleasure to remember, I never should be able tokeep on patching Elsie's petticoats, and darning Kittie's stockings. Iknow,--I know!--Rebecca Mary, that when you are young you live in thefuture, and when you are old you live in the past. Some one has saidthat memories are the only real fountain of youth. And that's true. Agirl is young such a short time that she has to cram the days full ifshe wants to be sure of a happy old age. I can't imagine anything moreawful than to have no good times to remember. And all pleasures aren'tlike the tea here. Such a lot of them can be had for nothing. You canget such fun just out of companionship, and the world is full of peoplewith whom we were meant to be friends. Why, life now means helping otherpeople to have a good time instead of moping off by yourself. You shouldknow that, Rebecca Mary. I know I sound like a sermon, but it is all sotrue. You must not turn your back to people and hide in a corner. Youmust face the world and take what you can and give what you can. I wishyou would promise me something?" she asked eagerly.

Rebecca Mary didn't look as if she would promise any one anything, butshe asked politely: "What would you like me to promise, Cousin Susan?"

"Just to say 'Yes, thank you' instead of 'No, I can't possibly,' whenyou are asked to do something or go somewhere," begged Cousin Susan,refusing to be discouraged by the scornful toss of Rebecca Mary's head."Please, Rebecca Mary! You talk so much about insurance and that sort ofthing that I'm going to ask you to take out some,"--she hesitated andthen laughed,--"memory insurance. We can't all hope to be money richwhen we are old, but we can all plan to be memory rich. Please promise?"

Rebecca Mary put her violets on the table and stared at her. "Your teais getting cold, Cousin Susan," she said stiffly. She shouldn't promiseanything so foolish. Cousin Susan was the most irresponsible old silly,but Rebecca Mary couldn't be irresponsible. There was too much dependentupon her. She drank her own tea and ate her sandwiches and even had abit of French pastry when Cousin Susan said she was going to try someeven if it did mean going without the new magazine she had planned tobuy to read on the way home.

"I can make the evening paper last longer," she said as she hesitatedbetween a strawberry tart and a cream-filled cornet. "I've read aboutFrench pastry for years, but we don't have it in Mifflin, and I neverhad a chance to taste it before. Isn't it good?"

Rebecca Mary said it was good, but inwardly she sniffed again and triedto think that it was ridiculous for a woman of Cousin Susan's age tobecome hysterical over a piece of pie. She could not understand CousinSusan's enjoyment of little things. She never would have dared to spendher kitchen curtains and new magazine for tea and French pastry. Itwould have been too foolishly extravagant. But she had enjoyed her tea.And it was exhilarating to be a part, even a shabby part, of a world shehad never penetrated before and never would again, she thoughtmournfully. That was the trouble with pleasant experiences, they cameall too seldom and were over far too soon. But Cousin Susan had saidwhen you had had a pleasant experience once you had it for ever. Perhapsthere was something in that thought. Rebecca Mary evidently thoughtthere was for her eyes were like stars as, with the violets pinned toher shabby coat, she followed Cousin Susan from the room.

She found herself in a crush at the door. Beside her was young PeterSimmons. Rebecca Mary thrilled as he brushed against her arm.

"Beg your pardon," he murmured absently, but he never looked at her.

It made Rebecca Mary so furious to be so coolly ignored that she did notsee that Joan Befort and her father pushed by her and that close ontheir heels were Mrs. Simmons and the man who looked as if he would dothings. The chattering laughing throng pressed closer. A hand eventouched Rebecca Mary's fingers. She drew them away with a shrug of hershoulders. She did hate to be jostled.

"My dear, I must fly!" exclaimed Cousin Susan when they had emerged atrifle breathless from the crowd. "But first give me that promise?Please, Rebecca Mary! What is that in your hand?" she broke off to asksuddenly, for something green hung from Rebecca Mary's worn brown glove.

"Why--why----" stammered Rebecca Mary as she opened her hand and found,of all things, a four-leaf clover. She stared from it to Cousin Susan.

"Where did you get that?" Like Rebecca Mary, Cousin Susan scanned thefaces hurrying by. Not one of them looked as if it belonged to a personwho would thrust a four-leaf clover into the fingers of a girl in ashabby blue serge. Four-leaf clovers had been no part of the tabledecorations. They never are. They belong in meadows and are only foundby patient seekers. Even Rebecca Mary had to admit that it was odd andthat it gave her a strange shivery sort of a feeling.

"My, but I'm glad I didn't buy curtains!" Cousin Susan was enchantedwith the mystery. "You simply will have to give me that promise now,Rebecca Mary. You are sure to have adventures if you do. There's thesign." She pointed to the crumpled clover leaf. "There's magic in it!"she whispered. Really, Cousin Susan was a silly.

"I wonder!" Rebecca Mary looked at the talisman. Where could it havecome from? Perhaps there was magic in it. There must have been, forsuddenly Rebecca Mary laughed softly. She straightened her shoulders andlooked into Cousin Susan's kind blue eyes. "Yes, Cousin Susan," she saidswiftly, as if the spell of the clover leaf might be broken if shedidn't speak in a hurry, "I promise to say 'Yes, thank you' instead of'No, I can't possibly.'"

And then before Cousin Susan could say how glad she was, right there onthe crowded avenue, Rebecca Mary put her arm around Cousin Susan andhugged her.

"I haven't been a bit nice this afternoon," she confessed frankly andwith considerable regret. "I've been horrid, but it was because I didfeel so out of place. But I do love you and--and I shall try and be moredecent to people. And if you really want me to take one of your oldmemory insurance policies," she giggled as she thought of Cousin Susanas an insurance agent, "why, of course I shall. Perhaps--" she lookeddown a

t the mysterious clover leaf, and her eyes crinkled--"perhaps thismight make a first payment."