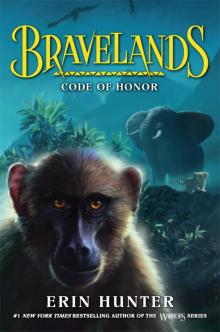

Code of Honor

Erin Hunter

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Special thanks to Clarissa Hutton and Gillian Philip

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Epilogue

Back Ads

About the Author

Books by Erin Hunter

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE

A thin golden glow edged the horizon to the east, bringing the first daylight to the savannah and revealing the flat-topped acacias that dotted the grassland. Another beautiful day, thought Babble the oxpecker: another delicious breakfast. He stretched, preened under a wing, then pecked a fat tick from the hide of the rhino he rode.

This rhinoceros was a talker. He had been arguing with the other members of his crash since before dawn broke. Babble couldn’t understand a word of their strange, ground-plodder language, but the conversation sounded urgent, agitated, and more than a little aggressive.

Babble raised his head and blinked. “Chatter?”

“Wait,” came a muffled voice. All that was visible of Chatter was his tail; the rest of him was deep in the rhino’s flickering ear. His tail wagged, and he popped out, gulping down whatever parasite he’d been digging for. “What is it?”

“I just wondered where you were,” Babble replied. “Is there anything else tasty in that ear? What do you think these rhinos are talking about?”

“No idea. I don’t speak Grasstongue any more than you do.” Chatter fluttered down the rhino’s broad neck. “I think I got the last tick, but you’re bound to find something in his other ear.”

Babble hopped past him, up to the rhino’s head. “I wish they’d stop all the horn-tossing and head-shaking,” he complained. “It’s not very calming. Or easy.”

“It’s a nuisance, but you know what old Prattle says,” Chatter told him, poking under a flap of leathery skin. “Don’t worry about today, because tomorrow there’ll still be insects.”

“Well, I wish Prattle would have a word with these rhinos,” sighed Babble. “They seem very wound up about something. They could learn a thing or two from us oxpeckers.”

“They certainly—oh!” Chatter peered up as the call of a gray crowned crane echoed above them.

The bird soared on vast white-and-black wings, shrieking in penetrating Skytongue: “Great Flock! Great Flock!” He angled his head, staring down at the two friends. “Great Flock!”

As the oxpeckers gazed up in awe, the crane circled and flapped away in the direction of the sunrise. Distantly, they heard him calling the same words over and over, to other birds on the ground and in the trees.

“Great Flock!” chirped Babble in delight.

Chatter blinked his round yellow eyes. “I’ve never been summoned to a Great Flock before. This is exciting!”

“Me neither,” said Babble. “I’ve been hearing stories about Great Flocks since I came out of the egg, but I’ve never been to one.”

“Let’s go, then!” Chatter darted his red beak at a last insect and took off.

Babble fluttered after him. The sun was rising above the horizon now, a half circle of dazzling gold, and the sky was a cool, clear blue that was filling with birds. Crows took off cawing from their rot-flesh feasts, egrets rose in a white-winged mass, and a flock of blue starlings erupted from a thorn tree. A pair of bright green-and-yellow bee-eaters zipped past Babble, almost touching his wing.

“Hey, watch where you’re going!” he chirruped, but he was too excited to be cross. The sky was growing dark with birds; many more were silhouetted against the glow of the rising sun.

“I wonder why a Great Flock’s been called?” exclaimed Chatter.

A shadow raced over them from high above. A great white-backed vulture circled there; the gathered birds rose to swoop and flap around her, their cries hushed to an expectant twittering. A whole flock of vultures flew in the huge bird’s wake, soaring on vast black wings.

“Isn’t that Windrider?” whispered Babble. “The old vulture who speaks with Great Mother?”

“I think so.” Chatter fluttered, watching her in awe.

The strange quietness was pierced by Windrider’s harsh, eerie cry.

“I bring terrible news, birds of Bravelands. Great Mother is dead.”

Screeches and chirrups of horror rose throughout the sky. Crows gave rasping caws of shock, and the mournful hooting of cranes mingled with a burst of disbelieving chittering from the starlings.

“No!” Chatter cried at Babble’s side. “This is terrible news!”

Babble was stunned. “No wonder the rhinos were upset. They must have known already!”

“Follow me.” Windrider’s command silenced the hubbub once more.

No bird argued; the flocks swooped and fluttered into a rough formation behind the vulture, and together the vast horde soared over the savannah, the sun gleaming and glinting on thousands of wings. The riot of colors dazzled Babble.

I wish the Great Flock could have been called for a happier reason, he thought.

Already he could see where Windrider was leading them; ahead and below, a large watering hole sparkled and glinted in the dawn. It was not the peaceful, happy place it should have been. Herds of grass-eaters milled and jostled on its banks, braying and bellowing in distress. As the birds flew lower, Babble saw a great stain on the water; something huge lay half submerged in the lake.

Great Mother.

Babble had never seen the wise old elephant before; now he wished he could never have seen her at all, if it had to be like this. She lay lifeless, torn by wounds that were dark with blood. Other elephants surrounded her, pushing desperately at her body; their enormous feet churned the bloodstained water as they struggled to get her to shore.

One of the elephants stood aside, though, staring at Great Mother. She looked young, thought Babble—smaller than the others, her legs trembling with shock. As he swooped lower he could see her huge dark eyes: filled with grief, but oddly wise for such a youngster.

The young elephant stood as if rooted to the mud, while around her grass-eaters trumpeted and bellowed, rearing up and stampeding. Zebras and wildebeests trotted to the shore, gaping at Great Mother’s corpse, then surged away in a thundering, panicked mass. The squeals of smaller animals rose, then were cut off abruptly as they were trampled underfoot.

Yet the young elephant stood unmoving. She seemed transfixed by the horror of the body.

Every bird was landing now, finding perches on trees and rocks and grassy slopes. The banks of the lake became a flurry of wings as they settled, but there was no clamor of calls; only an eerie, mournful silence. Windrider and her vultures gathered on the body of Great Mother itself, wings raised as if to protect her.

“This,” Windrider cried harshly into the stillness, “this is only the beginning of the turmoil that will come to Bravelands!”

She opened her beak to speak more, but a deafening crack of thunder split the sky. It crashed across the watering hole, rolling and resounding. Every

creature froze in shock; Babble hunched his head into his wings, terrified.

The sky was no longer clear and dawn-blue; it had been blotted out by a dark bank of cloud. Rain exploded, hammering down on the gathered creatures of Bravelands. Babble’s feathers were instantly drenched and sodden.

He stared at Chatter as rain streamed from their beaks and tails and wings. His friend looked as scared as he was.

“The Great Spirit is angry,” moaned Chatter, “because Great Mother is dead!”

Babble tried to shake rain from his wings, then gave up and squatted miserably, enduring the onslaught of the torrent.

“Perhaps Prattle was wrong,” he whispered. “Perhaps tomorrow won’t come after all. . . .”

CHAPTER 1

This rain was the hardest he’d ever known. Thorn staggered away from the watering hole, his paws clumsy in the thick mud, his fur sodden and dripping. He could barely see for the water that streamed down his forehead into his eyes; frantically he wiped it away, over and over again. Even his nostrils were full of it.

What happened? What happened?

Great Mother died. That was what had happened. But it didn’t matter how often he told himself; it still seemed unreal. How? Why?

It didn’t matter; the Great Parent of Bravelands was dead, and she couldn’t help Thorn now.

He’d gone to the watering hole to ask for her advice, her assistance, her wisdom—and because there was no other creature who could help him. Great Mother would have known how to deal with Stinger Crownleaf, he was sure. The enormity of Stinger’s crimes was more than any ordinary creature could comprehend. The devious baboon had murdered Bark Crownleaf, smashing her skull with a rock. He had poisoned Bark’s successor, Grub, with scorpion venom—clearing the way for Stinger himself to lead Brightforest Troop.

But when Thorn had confronted him, filled with righteous rage, Stinger had only laughed. His smirk still haunted Thorn, along with his certainty that he wouldn’t be brought to justice. Do you see how far I will go to protect Brightforest Troop?

Do you see how far I will go . . . ?

Thorn had known exactly what Stinger meant: he’d have no hesitation in killing Thorn, should he try to expose him to the troop. Thorn had had one chance to stop Stinger—one single place to look for help.

Now Great Mother was dead. And Thorn was utterly alone.

Dusk was a miserable, gray fading of the daylight; there was no sunset, no golden rays to stream through the branches of Tall Trees. Thorn crouched on the sodden earth of the Council Glade, mud soaking into his fur as if it were forming a second skin. All of Brightforest Troop was gathered before the Crown Stone; facing them were the Council members and their retinues, who flanked the broad, pale stone itself. Every baboon, from infant to aged councilor, looked drenched and dejected—except for Stinger Crownleaf. He couldn’t stop the rain, and he no doubt wasn’t pleased about his wet fur, but at least he had the Crown Stone to perch on.

“What do you think will happen, Thorn?” whispered Mud Lowleaf.

Thorn squeezed his shoulder. His best friend had always been small, but with his fur soaked through to his hide, he looked scrawnier than ever. “I don’t know, Mud,” he murmured. “Nothing like this has ever happened before.”

“I welcome you all.” Stinger’s commanding voice drew everyone’s attention. As the anxious chatter died away, he gazed around his troop with stern solemnity. “As you know, I would usually meet here only with my councilors, but the events Bravelands has witnessed today are unprecedented. Never—in all the history of these lands—has a Great Parent been murdered.” Stinger raised his eyes to the sky and closed them, as if seeking aid from the Great Spirit itself. “Together we must discuss what it means for us—for all of Brightforest Troop.”

Every baboon craned forward, eager for Stinger’s advice and wisdom. There was anxiety in their eyes, but also respect, and trust. Thorn’s spine felt cold. Just a day ago, I’d have looked at him like that.

“Mango!” called Stinger, gesturing with a long-fingered paw. “You have been scouting for news. Tell us what you have discovered.”

Mango Highleaf splashed forward through the mud and cleared her throat. “My Crownleaf, no one knows for sure what happened. But many animals say that the crocodiles killed Great Mother. The brutes’ tooth marks are on her body.”

“That’s appalling!” cried Moss Middleleaf.

“Those savages!” exclaimed Petal Goodleaf, her voice breaking with emotion.

Stinger spread his paws. “What do we expect of creatures who do not even follow the Great Parent?”

“They don’t even follow the Code!” shouted Splinter Middleleaf angrily. “Only kill to survive; why, we learn it as infants on our mothers’ bellies!”

Beetle Highleaf shuffled forward from the ranks of councilors. He was old and gnarled, and he had a whiff of fermented fruit about him, but all the baboons fell respectfully quiet as he spoke. “I have heard,” he said in his querulous voice, “that many died in the stampede at the watering hole. Such panic was perhaps to be expected—but it will almost certainly spread, rather than lessen.”

Stinger nodded thoughtfully. “The creatures of Bravelands have no guidance,” he murmured.

“And no one knows who the new Great Parent is,” pointed out Mango. “Great Mother did not have time to pass the Great Spirit to her successor, and that’s never happened before. What shall we do?”

Moss piped up in a small, scared voice. “Maybe the Great Spirit died with her.”

There was uproar. Baboons hooted in horror, others pounded the muddy ground, and babies began to wail.

“Quiet, quiet!” Stinger slapped the Crown Stone and rose to his paws. “My troop! Other animals may panic like disturbed ants, but we are baboons! We will stay calm, and keep our dignity!”

The hubbub faded. Mothers hushed their babies, and Moss, looking shamefaced, muttered, “Sorry, Stinger.”

Stinger turned to the baboon closest to him: Mud’s mother. “What does our Starleaf say? What do the Moonstones tell her?”

Starleaf’s white-streaked face was gentle and serene. Even Thorn felt calmer as she methodically laid the Moonstones before her. Each was a pebble of a different color: some were bright blue or green or orange; some were translucent, and sparkled even in the dim light; others were smooth and opaque. One was a broken shard of stone, its hollow insides revealing glittering crystals. One by one Starleaf held the stones up to examine them, her face creased in concentration.

At last she looked up, unsmiling—but then she never did smile when she was reading the Moonstones. Thorn shot an anxious glance at Mud, who nodded confidently.

“Stinger is right to call for calm,” declared Starleaf. “The Great Spirit will find the new Great Parent—of that, the stones are certain.”

“Well, that’s good news,” grunted Mango.

“But what if it’s an animal that’s unfavorable to us?” asked Bud Middleleaf nervously. “What if it’s, say, a cheetah?”

“Or a hyena,” squeaked Moss.

Starleaf gave her a kind but stern look. “The Great Spirit always chooses wisely.”

“That’s all very well,” said Beetle, “but I must say, every animal has its prejudices, and . . .”

As the discussion turned to the merits of various potential Great Parents, Thorn stopped listening. Berry Highleaf was sitting close to her father, Stinger, and she had said nothing so far. She listened to the speakers with an expression of vague concern, but mostly she seemed sad and hurt. And I know why, thought Thorn, with a wrench of guilty misery.

He felt dreadful for wounding her feelings so badly the previous night. If only she knew why he had really done it. When Thorn had told her they should stop seeing each other, it wasn’t because he wanted it that way. I did it to protect you, Berry.

But to do that, to keep her safe, Thorn had had to pretend the reason was their different ranks. He’d told her they couldn’t disobey the troop’s rules anymo

re; they must respect the laws and traditions that said Highleaves could never pair with Middleleaves.

Berry must have despised him for saying it, but he’d had no choice. Thorn was all too aware of what Stinger could do. If he found out that his daughter was involved with the one baboon who knew his secrets, or if Thorn accidentally let slip part of the truth, then Berry would be in terrible danger. Stinger might love his daughter, but he loved himself even more.

“Thorn,” whispered Mud, “what’s happened between you two? Berry hasn’t spoken to you since you got back.”

“It’s nothing.” Thorn shook himself, annoyed that he’d been staring so obviously at Berry.

“It’s my fault, isn’t it?” Mud rubbed his head and groaned. “You’ve fallen out because of me. You’d be a Highleaf right now if I hadn’t beaten you in the Three Feats duel.”

“No,” Thorn said firmly. “Really, Mud, it’s not that.”

“Because I feel bad, and—”

“Hah. No need to feel bad!” A voice interrupted Mud, rather to Thorn’s relief. He turned to see Grass Highleaf. The tall baboon was chewing on his usual grass stalk, eyeing Mud with amused disdain. His skinny friend Fly wore a cruel, chip-toothed grin. Along with Thorn, both had been part of Stinger’s retinue when he was merely Stinger Highleaf, Council member.

“Yeah, don’t feel bad, Mud,” sneered Fly. “You didn’t beat Thorn—he threw the fight to let you win.”

“It was so obvious.” Grass grinned.

“Don’t talk hyena droppings,” snapped Thorn, with a quick glance at Mud’s shocked face. “Mud, don’t listen to them. You won fair and square.”

Fly giggled. “Thorn-y subject?”

Grass hooted and slapped his leg. Thorn glared at the pair of them. The fact was, they were telling the truth. He had thrown the fight. If Mud had lost his final Feat, he’d have been condemned to stay a Deeproot all his life—and that meant a miserable life of cleaning the camp and taking orders from the rest of the troop.

But there was no way Mud could ever know this.

“Get lost, you dung-stirrers!” he snarled at the grinning pair.

“Who’s going to make us—yo— Ow!” Grass clutched his head and staggered back. An unripe mango had struck him right on the forehead.