Long Ride Home

Elizabeth Hunter

Contents

Long Ride Home

Night One

Day One

Night Two

Day Two

Night Three

Day Three

Also by Elizabeth Hunter

Acknowledgements

About the Author

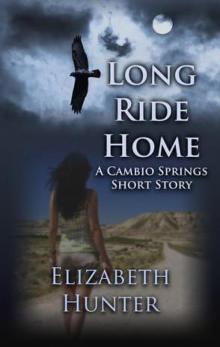

Long Ride Home

A Cambio Springs Short Story

By Elizabeth Hunter

Long Ride Home

Copyright © 2012

by Elizabeth Hunter

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or by any information storage retrieval system without the written permission of the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the products of the author’s imagination, or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Cover Design: Flickers and Frames

Edited by: Amy Eye

Formatted by: E. Hunter

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book via the internet or any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

For more information on Elizabeth Hunter’s work, please visit:

ElizabethHunterWrites.com

To new dreams

Night One

Oregon Coast

April 2007

Jena Crowe McCann was driving down the Oregon coast and breathing in the cool night air when her husband’s ghost appeared to her. She slid her hand along the car door, pressing down the button that would crack the window open so the smell of salt and pine filled the air. Then she took a deep breath, holding the fragrance in her lungs for as long as she could before she let out a long sigh.

Lowell’s ghost kept her company, silently watching the oncoming lights and occasionally glancing over a phantom shoulder at his sons. The boys were sleeping in the backseat, both exhausted after a final day of packing and saying goodbye to friends and the suffocating helpfulness of their neighbors. His ashes rested in a simple urn carved from cedar, which was placed into a box with a few other mementos from his too-short life. Jena would give the box to his parents when she and the boys got home.

Home.

“I’m going to miss that smell,” Lowell said.

Jena glanced over. “Can you smell that? Really?”

His shadowy outline frowned. “I’m not sure if I can smell it, or I just remember the smell of it.”

“Well, that clears everything up.”

“Hey, I’m as new at this being a ghost business as you are at seeing ghosts.”

“I don’t see ghosts. I just see you.”

“Really? Never before?”

“Don’t you think I would have told you if I saw ghosts?”

Lowell smiled and leaned back in the seat, turning his head so he stared at her profile in the low light from the dashboard. “I don’t know. You always had your secrets.”

“I didn’t keep secrets from you.”

“I didn’t say you kept them from me, just that you had them. It’s okay. I like that I never figured you out completely. You were my favorite puzzle.”

A sharp ache pierced her heart. “Am I still going to see you when we get there?”

“I don’t know.”

She drove on in silence, listening to his soft voice as she navigated the twisting roads lined by dark conifers.

“Do you think I’m making a mistake?” Jena asked. “Moving so soon?”

“No. It’s a good move. It’ll be a new start for all of you.”

“I feel like I’m moving backward.”

“Nah.” He grinned. “Moving back, not backward.”

“What’s the difference?”

“You know. You’re just not seeing it.” He crossed his arms. Arms that had once held her tightly. Held their sons. Thrown darts at their favorite pub in college. Arms that had carried her name. The boys’ names. Favorite verses and patterns tattooed permanently onto all too un-permanent skin.

“I miss your arms, Low.”

“I miss your everything.”

She blinked back tears and forced herself to focus on the road. In the rearview mirror, she saw her youngest, Aaron, shift in his seat. Lowell turned his head to stare at the small boy who was the spitting image of himself.

“The boys need this, Jena. They need to be around family. Even my crazy people.”

“Don’t forget mine.”

“Them too. And our friends. And Joe and Allie’s kids. Ted and Ollie and everyone. They need to be in a place where they’re going to be understood. Where they won’t have to hide.”

“I’m afraid for them.”

He frowned. “Because of me? That’s not how it works; you know that.”

“Still, I worry.”

“You’re a mom. It’s part of your job.”

She sniffed. “Damn straight it is.”

Lowell grinned again. “That’s my girl. You’ll watch them like a hawk.”

“Haha.”

He took a deep breath, letting it out slowly as he watched the road ahead. “It’s the right move. The boys need to go to your mom and dad’s diner every day after school for a milkshake and help with their homework. They need to go fishing with my dad or pull weeds with my mom at the park while she lectures them about native plant species and water conservation. They need all that stuff. And you do, too.”

“I’m pretty well educated about water conservation already, thanks.”

He laughed. “You know what I mean.”

“I do.” She swallowed the lump in her throat. “I’m going to end up working the grill at Dad’s diner.”

“You’ll class up the place.”

“It’s not exactly why I went to culinary school.”

“I don’t know.” He settled back, turning his eyes toward the dark road ahead. “You liked Cartwright well enough. It’s as small as the Springs.”

“Nothing’s as small as the Springs. And Cartwright was a college town. It may have been small, but there were plenty of food snobs with disposable incomes to experiment on.”

He shifted again, and Jena had to pinch herself. There was no sound when he moved, except the expected whistle of the night wind at the window and the soft snoring of eight-year-old Low Jr. in the backseat.

“Well, now you’ll have truckers, farmers, and desert eccentrics to experiment on. The town could use a little shake-up. You’re just the woman to bring it. Your dad won’t bat an eye when you add duck confit hash to the breakfast menu. It’ll go great with a side of your mom’s gravy.”

Jena winced. “That’s wrong on so many levels. I’m not even going to respond.”

Lowell laughed, the rich, welcome sound echoing in the tightly packed car. He looked over his shoulder at the sleeping boys. He watched them silently for a few moments, then looked around the car before his green eyes settled on Jena.

“I’m glad we spent the money on the Subaru. You’ll like the all-wheel drive out in the desert. This thing will last a long time. Really safe, too.”

Jena looked over to meet his eyes when the road straightened out. A smile lingered on his lips and blond hair fell over his forehead. He looked the same. He looked better. Like he had when he was a vibrant young man, before the cancer had ravaged his body and stolen the light from his eyes.

“Mom?”

<

br /> Jena blinked away her tears, and he was gone. She looked into the rearview mirror at her five-year-old son. “What’s up?”

Aaron yawned, his round cheeks stretching as his arms reached out, whacking his older brother, who grunted and shifted away.

“I need to go potty. When do we get there?”

“Not for a while, Bear. We’ll stop for a break, okay?”

“Okay.”

Jena stared at the urn in the passenger seat for a moment before she turned her eyes back to the road and kept driving.

Day One

Northern California

Out of the corner of her eye, Jena saw Aaron blow hot breath on the window before his small finger squeaked out the figure of a tree that matched the towering pines soaring along the side of the road.

“Mom, will there be trees there?”

Low Jr. said, “Stupid, you’ve been there before. We’re just moving to Grandpa and Grandma Crowe’s house.”

“Mom! He called me—”

“Low, don’t call your brother stupid. And yes, there are trees but not this many.”

“Mostly weird Joshua trees,” Low mumbled. “They’re not really trees. Not real ones. I told you, Aaron. It’s the same place we go every Christmas.”

Aaron’s small forehead wrinkled. “But we didn’t live there, then.”

Low sighed and his voice softened. “Bear, a place doesn’t change just because you’re moving there instead of visiting.”

“Well, I didn’t know that. I’ve never moved before.”

“Yeah, you have. We moved four years ago.”

Jena glanced up. “You remember that, Low? You were only four.”

Her oldest son slumped down. “No.” He looked out the window. “Dad told me about it.”

Jena didn’t say anything. Lowell and she had planned the move back to their childhood home as soon as he was diagnosed, resigned that they hadn’t managed to outrun the peculiar curse that had kept them away for so long. If he’d lasted longer, Lowell would have joined them, but the cancer that attacked his brain had shown no mercy. Her husband was gone within five months.

“If you were four, then how old was I?” Aaron asked.

“One.” Jena smiled. “And you wanted to get down and walk everywhere. We put your portable crib up in the living room and you chattered to every one of our friends who were helping us move.”

“But you liked it, right Mom?”

She smiled. “Yep. You were telling me stories even then; I just didn’t understand ‘em.”

Aaron grinned. “What did you do, Low?”

Low was still staring out the window sullenly, so Jena answered. “He mostly hung out with Daddy and Grandpa Max.”

Thick as thieves. Despite their different temperaments, her oldest son and her husband had been inseparable. She saw Low blinking hard and tried to distract him. “Hey, Low, Grandpa Max says he has a fishing trip all planned out for next weekend.”

Aaron piped up. “Can I go, too?”

“I think so.”

Low finally spoke. “I don’t know. It might be a real fishing trip. Not one for babies.”

“Mom! Low called me a—”

“Don’t call your brother a baby, Lowell.”

The boy muttered, “Don’t call me Lowell, Jena.”

A red haze fell over her eyes and Jena swung the car to the curb with a jerk. Thank God they were on a wide stretch of road. She shut off the car and got out, walking around to pull open her son’s door. She could already see the embarrassed tears in Low’s eyes as he unbuckled his seatbelt. Aaron stared at them both, open-mouthed.

She slammed the door after he stepped out, marched him to the back of the car, beyond the sight of his younger brother, then spun on him.

“Not in a million years, Lowell McCann! Not in a million years do you talk to me that way. Do you understand?”

He blinked hard and the tears rolled down his red cheeks. “Yes, ma’am,” he whispered.

“What do you think your father would say if he heard you?”

“He’d be mad.”

“You bet he would.” Jena was blinking away her own tears as she stood in front of her son with her hands on her hips. His shoulders were slumped, and he was sniffing and wiping his nose with the sleeve of his T-shirt. In a second, Jena swept him into her arms and held tight. She could feel Low’s tears soaking her collar as she bent down to his ear.

“Aaron doesn’t understand any of this, buddy. And I know there’s a lot that you don’t understand either. Hell—don’t use that word—there’s a lot I don’t understand, but I know this is the right thing. And it’s what your dad wanted. I know you miss your friends and—”

“It’s not about my friends,” he mumbled.

Jena stroked his thick brown hair, so like her own. “I know it’s not. But you’re giving up a lot more in this move than Aaron is. I know that.”

“Why did he want us to move, Mom? He loved it in Oregon.”

“I know.” She paused and watched the Subaru rock as a truck drove past, then peeked inside to see Aaron craning his neck to watch them. “He did, but he loved us more. And he knew…” Oh, Lowell, what did you think you knew? Why were you so adamant about going back to a place we tried so hard to leave?

Low was still looking at her like a lost child. Jena said, “Your dad knew the Springs were going to be the best place for us. That we needed to be there, I guess.”

“But why?”

So many reasons. But Jena said, “For family. You’ll find out when we get there. And as much as I’m not looking forward to it, I think Dad was right. I think we need to go back. Otherwise, we wouldn’t be doing this.”

They stood in silence, Jena’s arms still wrapped around her tall boy. Low finally said, “I’m sorry, Mom.”

“I know.”

“You only called Dad ‘Lowell.’”

“That’s not completely true. I call you ‘Lowell’ when I’m really mad at you.”

He sniffed again. “Are you still mad?”

“You ever going to call me Jena again?”

“Only if we’re at the grocery store, and you’re not answering to ‘Mom.’”

“Promise?”

“Promise.”

She ruffled his hair and walked him back to his side of the car, reaching into the front seat to grab a bunch of Kleenex. She handed a few to Low, then blew her own nose, closing her eyes as she sent up a silent plea. Oh, Lowell, I hope you know what you’re doing. By the time she walked back to the driver’s seat, Aaron and Low were talking again.

“—but there are trees, right?”

“There’s not a lot, but there’s a few. And there’s more by the Springs and the river where Grandpa will take us fishing. Not just Joshua trees. But Joshua trees are really kind of cool.” Low glanced at Jena as she started the car. “They look like some of those weird trees in Dr. Seuss books.”

“Cool! Can we have one in our yard?” Aaron asked.

“You mean Grandpa and Grandma’s yard?”

Jena said, “Hey, we’re going to have our own yard eventually.”

“Mom, can we have a Joshua tree for a Christmas tree?”

Low snorted. “Goof, you can’t use a Joshua tree for Christmas.”

“Mom! Low called me a—”

“Aaron, let it go.”

She heard Low cackle from the backseat as Aaron huffed and slumped down below her line of vision in the rear view mirror.

It was going to be a long ride home.

Night Two

Central California Coast

“You knew going into this that I wasn’t a good long-term prospect, Jena.”

“You’re an awful big smart-ass for a ghost.”

“You always had a weakness for smart-asses.” Low grinned again. In that moment, he was the boy who threw toads at her while she was in her Easter dress. The awkward twelve-year-old who was shorter than her and pissed-off about it. The rangy high school boy who gave Jen

a her first kiss. The boy she married at eighteen, crazy in love and knowing in her heart that she didn’t have long.

His grin turned into a soft smile and ghostly fingers trailed down her cheek. “We had long enough.”

“No, we didn’t.”

He glanced over his shoulder at the sunburned, sandy boys, who had played hard on the beach in Monterey after a visit to the aquarium. They would stop the next morning at a college friend’s house in Santa Barbara. Jena still felt like driving at night with the window cracked open to the night air. That night, the scent of cedar and eucalyptus filled the salty ocean air as they drove along Highway One. She was tired, but if she drove at night, she knew Lowell would keep her company. Once again, in her heart, she knew she didn’t have long.

“You know, if we’d had longer,” he said, “I probably would have knocked you up at least twice more. We have very cool kids.”

She managed a smile. “We do. They’re loud and obnoxious and brilliant.”

“And completely ours.”

She glanced at him, noticing the look of quiet awe. He’d always watched the boys that way when they slept, like he couldn’t quite imagine that they existed. In a way, it was extraordinary they did.

“We had longer than most,” she whispered.

“Yeah.”

She tried to lighten the heavy atmosphere in the car before she choked up. “And really, the fact that you survived until adulthood is a miracle in itself, considering how clumsy you were.”

He scowled. “I wasn’t clumsy.”

“Tree house. That’s all I’m gonna say.”

“That was not an accident! I—I pushed you.”

Jena threw her head back and laughed. “Only you would try to cover up clumsiness as aggression! You didn’t have a mean bone in your body, Lowell McCann, and you would never have pushed a girl out of a tree house on purpose. Clumsy.”

“I was devious.” He nodded, and his lower lip stuck out thoughtfully. “I was so devious that I made everyone think I was a nice kid.”