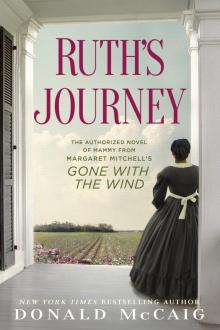

Ruth's Journey: The Authorized Novel of Mammy From Margaret Mitchell's Gone With the Wind

Donald McCaig

Thank you for downloading this Atria Books eBook.

* * *

Sign up for our newsletter and receive special offers, access to bonus content, and info on the latest new releases and other great eBooks from Atria Books and Simon & Schuster.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

For Hattie McDaniel

“My own life even surprises me.”

A huge old woman with the small, shrewd eyes of an elephant. She was shining black, pure African, devoted to her last drop of blood to the O’Haras, Ellen’s mainstay, the despair of her three daughters, the terror of the other house servants.

—MARGARET MITCHELL, GONE WITH THE WIND

Whither thou goest, I will go; and where thou lodgest, I will lodge: thy people shall be my people, and thy God my God: where thou diest, will I die, and there will I be buried.

—BOOK OF RUTH

PART ONE

Saint-Domingue

HER STORY BEGAN with a miracle. It was not a remarkable miracle; the Red Sea did not part and Lazarus didn’t rise up. Hers was one of those everyday miracles that part the quick from the dead.

The miracle happened on a small island which had been a very rich small island. The island’s planters called it the Pearl of the Antilles. Three weeks after The Marriage of Figaro opened in Paris, it played Cap-Français, the small island’s capital city. The island’s planters, overseers, and second sons ruled sugar and coffee plantations that made rich Frenchmen richer and propelled unimportant shipping merchants into the bourgeoisie. Every year the island produced more revenue than all Britain’s North American colonies combined.

But that was olden times. These days fertile cane fields lay fallow under thick black ash, and the broken cornerstones of once grand mansions peeked beneath rude thornbushes.

If they were prudent and kept to the roads, Napoleon’s soldiers could still patrol the Plaine-du-Nord at least as far as Villeneauve. Their ring forts were safe enough.

But when night fell they bivouacked inside those forts or returned to Cap-Français. Day or night, the mountains belonged to feral hogs, goats, insurgents, and Maroons.

* * *

The afternoon of the miracle, the woman who would become the child’s owner and almost mother sat beside her window looking east over the broken rooftops of the capital and the mastheads of the blockaded French fleet to the gentle azure bay because every other vista rejected hope. And Solange Escarlette Fornier turned to hope as the fleur-de-lis inclines persistently to the sun.

Though Solange was young she wasn’t beautiful. Two years ago on her wedding day, in her grandmother’s Flemish lace gown and jewels, Solange had been plain. But those who spared Solange a second glance often found time for a third, lingering on her high cheekbones, her cold gray-green eyes, her arrogant Gallic nose, and her mouth, which promised much it withheld.

That second glance revealed how this young woman’s loneliness made her invulnerable.

Solange Escarlette Fornier had been reared in Saint-Malo, the thriving port on the Breton coast. She understood her home, and when she spoke her hands employed the subtle gestures of the native. Solange knew how Saint-Malo skeins had been wound by what hands and of what wool.

Here, on this small island, Solange Escarlette Fornier was a cipher—a provincial bride without influential Paris kinsmen, married to an undistinguished captain in a dying army. Solange couldn’t understand why these terrible things were happening, and though she blamed her husband, Augustin, she reserved more blame for herself: how could she have been so stupid?

Among Saint-Malo’s bourgeoisie, the Forniers were “considerable” and the Escarlettes “redoubtable.” Henri-Paul Fornier and Solange’s father, Charles, hoped to join their houses with marriage. Henri-Paul’s schooners would carry Escarlette manufactures, while Escarlette influence could tame greedy port officials. Every ship needs two anchors.

Courteously and candidly, the fathers evaluated the prospective bride and groom for, as another Breton saying has it, “love and poverty make an untidy household.”

Love? In the presence of Charles Escarlette’s eldest daughter, young Augustin Fornier was blushing and speechless, and if Solange was indifferent to her suitor, no matter. Doubtless, like countless girls before, Solange would come around.

Poverty? During the fathers’ dotal discussions, the son’s prospects were carefully balanced against the daughter’s substantial dowry.

To the marriage, Augustin would bring ninety percent (Henri-Paul reserved an interest) of a distant plantation: the Sucarie du Jardin of 150 hectares, improved by a great house (“a Versailles!”), and a modern sugar mill (“the whiter the sugar, the better the price, is it not so?”), and forty-three (“docile, loyal”) field hands no younger than fifteen or older than thirty years, not to mention twelve female slaves of childbearing age and numerous children, some of whom would survive to enter the workforce.

Henri-Paul produced records of quarterly receipts deposited in the Banque de France.

“One hundred twenty ecus,” Charles said. “Commendable.” He hummed as he riffled the papers and paused to jot a note. “Very handsome. Have you more recent accounts? From the last three years, perhaps?”

Henri-Paul took his pipe from his pocket, considered but put it away. “Events.”

“Just so. Events . . .”

Charles Escarlette knew there could be no recent accounts, but he’d indulged himself, just a little.

Twenty years earlier, when Henri-Paul mortgaged two small coastal schooners to buy a sugar plantation on a Caribbean island few Saint-Malouins had heard of, Charles Escarlette hadn’t been among the loudest scoffers, but he had raised an eyebrow.

Henri-Paul’s “improvidence” became “sagacity” when European demand for sugar doubled, tripled, and quadrupled. Even the poorest household must have its jams and cakes. No soil was better suited for sugarcane than the small island’s, and no plantation refined whiter sugar than the Sucarie du Jardin. The first year Henri-Paul owned the plantation, his overseer delivered profits which reimbursed the purchase. Subsequently, Henri-Paul had used profits from this venture to expand his fleet to eight coastal vessels (which became his elder son, Leo’s patrimony), and the Forniers were invited to join la Société des Expéditeurs et des Marchand, at whose annual ball Henri-Paul (who’d had one glass too many) clapped Charles Escarlette on the shoulder and addressed him with the familiar “tu.”

That unfortunate “tu” is why Charles asked for accounts which could not possibly be forthcoming.

For ungrateful slaves on that rich small island had revolted against their legitimate owners. As the slave revolt spread, metropolitan Frenchmen independently started a revolution of their own and executed their king. The revolutionary government, those unbusinesslike Jacobins (who lived in Paris and probably didn’t own one cubit of one sucarie!), in an excess of “Liberté! Égalité! Fraternité!” had freed every French slave!

Some years later, with Napoleon Bonaparte controlling the French government, conditions on the small island remained disordered, dangerous, and distinctly unprofitable. A self-appointed Negro governor-general sought to retain ties with France (while distributing its finest plantations to his supporters), and other rebels contested his rule and stole plantations for themselves.

Charles Escarlette understood that Henri-Paul wouldn’t have assigned ninety percent of the Sucarie du Jardin to his son Augustin if profits had been guaranteed, but he smiled in a most agreeable manner and opened a bottle of Armagnac sealed the same year the late lamented Louis ascended the throne. Henri-Paul was appreciative.

On his second glass Henri-Paul noted that Solange’s hips and breasts could produce and nourish strong grandsons but added, “My Augustin won’t wear the pants in that family.”

Charles swirled his Armagnac to savor its bloom. “Augustin will always need guidance.”

Gloomily, “He would have made a good priest.”

Snort. “He doesn’t eye my daughter like a priest!”

“As some priests do, perhaps.”

Instant bonhomie. The two, who’d been anticlerics in their youth, chuckled. Charles Escarlette tumped the cork back in the bottle and offered his hand. “Tomorrow, again?”

“At your convenience.”

* * *

Augustin Fornier was not entirely unsuitable as a prospective son-in-law, but he wouldn’t have been chosen except for that faraway sucarie and the intervention of Napoleon himself.

As Charles and Henri-Paul wanted the Sucarie du Jardin restored to French ownership, Napoleon wanted the small island’s wealth delivered to France instead of enriching quarreling Negroes who had been French property until a stupid Jacobin mistake was made. Moreover, pushy Americans had been sniffing around New Orleans, hub of the enormous Louisiana Territory, and a strong French force on the small island would check American ambitions. The French and British were presently at peace, the seas were open, and Napoleon’s splendid army had very little to do. The First Consul entrusted command of a large expeditionary force to his own brother-in-law, General Charles-Victor-Emmanuel Leclerc.

After his discussion with Fornier, Charles Escarlette interviewed Ricard d’Ageau, who’d lost an arm at Austerlitz, becoming thereby Saint-Malo’s authority on military matters. Ricard gratefully accepted Escarlette’s second best cognac before laying a judicious finger aside his nose and announcing that after Leclerc’s expedition landed and reassembled, there’d be three, perhaps four skirmishes, Leclerc would edify the populace with hangings, and affairs would return to normal within weeks, not months. Faced by French guns manned by Napoleon’s veterans, “Les Nègres will run like Toulouse geese.”

“And then.”

“Ha, ha. To the victor goes the spoils!”

This last prognostication fit all too perfectly with Charles Escarlette’s suspicions, and he spent a restless night and was grumpy at the breakfast table. When Solange asked her “dear Papa” if something was wrong, he replied so sharply, she stared at him as if he were a lunatic encountered on the street.

But not long after, his mind and duty became clear. It only remained to get Henri-Paul (“tu” indeed!) to understand the reality and opportunities of the situation.

Augustin Fornier had spent two chaparoned afternoons with his young potential bride. Though innocent of the fairer sex and life beyond the walled courtyard of the Fornier establishment at 24, rue des Pêcheurs, even Augustin—when his love delirium subsided—even Augustin knew his beloved Solange Escarlette was provincial, haughty, indifferent, and self-absorbed. What of it? Love is no bookkeeper.

He ached for her. The mole beside her left eyebrow was located exactly where the perfect mole should be, Le Bon Dieu had designed her breasts to repose in Augustin’s hands, her plump buttocks were shaped so he could clasp her to him. Imagining that triumphant moment when he’d possess Solange ruined Augustin’s sleep and twisted his sweaty sheets into ropes. Can one build a marriage on desire? Augustin didn’t know and didn’t care.

Solange thought marriage would mean a week of lording it over her unmarried sisters and the tedious duties of the marriage bed with a man she thought nice enough. Duty was duty, not so? Her father had arranged her christening, her schooling to twelve years, and now her marriage. That was how things were done in Saint-Malo.

The deal was struck and the pair wed. With a loan two points above the prime rate, secured by the sucarie, Charles Escarlette purchased a sublieutenant’s commission in the Fifth Légère for his son-in-law.

As a boy, Augustin had been pacific. When other boys flourished wooden sabers, Augustin worried someone might poke his eye out. When those boys became men and their stick swords sabers, the glistening steel made Augustin shudder. But his father-in-law explained: “The Sucarie du Jardin is your entire competence; not so? After General Leclerc breaks this revolt and our Negroes return to work, will the Sucarie du Jardin return to its rightful owners or to one of Leclerc’s favorite officers?”

Charles clapped Augustin on the back. “Don’t worry, my boy. It’ll be over before you know it and”—he coughed—“I’m told Negro women are . . . primitive.”

Augustin, whose possession of his bride had been rather less thrilling than he’d hoped, thought “primitive” might not be the worst thing in the world.

Henri-Paul blamed his son’s “indiscreet ardor” for the “régime de in fiparatum de bient” he’d been forced to accept. Solange Escarlette Fornier’s substantial dowry had been deposited in the Banque de France—in Solange’s name.

“My dear friend,” Charles encouraged his new relation, “they will need that money to restore the sucarie. Before the year is out your ten percent will be earning again.”

Solange thought she might rather enjoy being mistress of a Grand Plantation, and her sisters were quite annoyed at her presumptions. She’d be gracious, kind, and, if not beautiful (Solange was a realist) very, very well dressed.

Sundays after Mass she’d entertain other planters’ wives, serving tea with her grandmother’s cobalt blue and gold Sevres tea set. She’d be wearing her grandmother’s necklace, and a servant would stand behind each chair, fanning her friends.

The new-minted couple embarked in Brest and sailed west through choppy winter seas for forty-two days. Augustin’s sublieutenant rank commanded a bunk in a minuscule cabin the newlyweds shared with two unmarried officers no more important than they. Pretending they didn’t see or hear what inevitably they must was delicacy’s refuge. Since there wasn’t enough room to quarrel, Solange made do with her eyes.

For one splendid moment the morning of January 29, it all seemed possible. On the crowded deck as the small island grew larger, Solange slipped her little hand into her husband’s. Perhaps her sweet dependency brought the tears to Sublieutenant Fornier’s eyes, but perhaps it was the island breeze, spiced with gentle languorous perfumes. It was true! The officer-planter and his bride inhaled the promise of the Pearl of the Antilles.

Since insurrectionists had removed channel markers in Cap-Français’s harbor, General Leclerc’s expedition, including the Fifth Brigade and its novice sublieutenant, sailed down the coast to make their landing and Solange had the minuscule cabin to herself.

While the French fleet waited for Leclerc to strike, insurgents set fire to the capital city and a bitter stench masked the aromatic breezes. To hell with the navigation markers! The admiral sailed in and moored at the quay. The French landing party was sailors, marines, and civilians like Solange, brandishing an unladylike dagger and greeted by several hundred black children calling “Papa Blan, Papa Blan” (White Father). As the landing party looted, Solange commandeered children to carry Fornier baggage to a neighborhood which had been spared the flames.

Solange perched on the stone stoop of a small two-story stone house with her dagger across her knees until that evening, when General Leclerc’s forces arrived to join the looting. Two days later, an officer with proud grenadier’s mustachios informed Solange that not enough houses had survived the fire and hers was required for superior officers.

“Non.”

“Madame?”

“Non. This house is small and dirty and e

verything is broken, but it must suffice.”

“Madame!”

“Will you remove a French planter’s wife by force?”

Later, Augustin made himself scarce when other officers made futile attempts to dislodge his wife.

* * *

For a time Napoleon’s plan succeeded. Many islanders welcomed French help to end the revolt, and many of the governor-general’s black regiments joined the French. Houses were repaired and reroofed, and Cap-Français rose from its ashes. Leclerc sent most of the French fleet home. Many rebel commanders renewed fealty to France and its First Consul. The self-appointed governor-general was enticed to a peace conference, where he was arrested.

The Forniers drove out to inspect their sucarie. It was a cool misty morning on the Plaine-du-Nord, and Solange wore a wool wrap. The plain was dominated by hulking Morne Jean, which gave birth to big and little streams interrupting their passage.

In tiny villages, silent, emaciated children peeked at them and feral dogs slunk away. Some cane fields had been abandoned to brush, some subdivided into the small garden tracts and rude dwellings of the new freedmen; a few were solid with unharvested cane. They forded gurgling creeks and were ferried across the murky Grande-Rivière-du-Nord, whose banks were littered with broken limbs and tree trunks deposited by winter floods.

South of the Segur crossroads, they turned in to their fount of future happiness: the Sucarie du Jardin.

They had read the overseer’s reports, deeds and plats of a remote, mysterious Caribbean plantation; today they left real wheel marks in a disused lane in cool shadow between walls of sugarcane waving above their heads. “Vanilla,” Solange whispered. “It smells like vanilla.”

Cane rustled. Anything might be concealed in that cane, and they were relieved emerging into sunlight on the cobbled drive fronting a two-story plantation house which hadn’t been as grand as their imaginings even before it was burned. Blue-gray sky, punctuated with blackened roof beams, filled upper-story windows. Rubble spewed out of what had been its front door.