On Basilisk Station

David Weber

On Basilisk Station

by David Weber

This is a work of fiction. All the characters and events portrayed in this book are fictional, and any resemblance to real people or incidents is purely coincidental.

Copyright © 1993 by David M. Weber

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form.

A Baen Books Original

Baen Publishing Enterprises

P.O. Box 1403

Riverdale, NY 10471

ISBN: 0-7434-3571-0

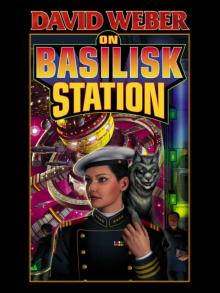

Cover art by David Mattingly

First hardcover printing, March 1999

Distributed by Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Weber, David 1952–

On Basilisk Station / David Weber.

p. cm.

ISBN 0-7434-3571-0

I. Title II. Title: Honor Harrington on Basilisk Station.

PS3573.E21705 1999 98-32222

813'.54—dc21 CIP

Production by Windhaven Press, Auburn, NH

Printed in the United States of America

PROLOGUE

To C. S. Forester,

With thanks for hours of enjoyment,

years of inspiration,

and a lifetime of admiration.

The ticking of the conference room's antique clock was deafening as the Hereditary President of the People's Republic of Haven stared at his military cabinet. The Secretary of the Economy looked away uncomfortably, but the Secretary of War and her uniformed subordinates were almost defiant.

"Are you serious?" President Harris demanded.

"I'm afraid so," Secretary Frankel said unhappily. He shuffled through his memo chips and made himself meet the president's eyes. "The last three quarters all confirm the projection, Sid." He glowered sideways at his military colleague. "It's the naval budget. We can't keep adding ships this way without—"

"If we don't keep adding them," Elaine Dumarest broke in sharply, "the wheels come off. We're riding a neotiger, Mr. President. At least a third of the occupied planets still have crackpot 'liberation' groups, and even if they didn't, everyone on our borders is arming to the teeth. It's only a matter of time until one of them jumps us."

"I think you're overreacting, Elaine," Ronald Bergren put in. The Secretary for Foreign Affairs rubbed his pencil-thin mustache and frowned at her. "Certainly they're arming—I would be, too, in their place—but none of them are strong enough to take us on."

"Perhaps not just now," Admiral Parnell said bleakly, "but if we get tied down elsewhere or any large-scale revolt breaks out, some of them are going to be tempted into trying a smash and grab. That's why we need more ships. And, with all due respect to Mr. Frankel," the CNO added, not sounding particularly respectful, "it isn't the Fleet budget that's breaking the bank. It's the increases in the Basic Living Stipend. We've got to tell the Dolists that any trough has a bottom and get them to stop swilling long enough to get our feet back under us. If we could just get those useless drones off our backs, even for a few years—"

"Oh, that's a wonderful idea!" Frankel snarled. "Those BLS increases are all that's keeping the mob in check! They supported the wars to support their standard of living, and if we don't—"

"That's enough!" President Harris slammed his hand down on the table and glared at them all in the shocked silence. He let the stillness linger a moment, then leaned back and sighed. "We're not going to achieve anything by calling names and pointing fingers," he said more mildly. "Let's face it—the DuQuesene Plan hasn't proved the answer we thought it would."

"I have to disagree, Mr. President," Dumarest said. "The basic plan remains sound, and it's not as if we have any other choice now. We simply failed to make sufficient allowance for the expenses involved."

"And for the revenues it would generate," Frankel added in a gloomy tone. "There's a limit to how hard we can squeeze the planetary economies, but without more income, we can't maintain our BLS expenditures and produce a military powerful enough to hold what we've got."

"How much time do we have?" Harris asked.

"I can't say for certain. I can paper over the cracks for a while, maybe even maintain a facade of affluence, by robbing Peter to pay Paul. But unless the spending curves change radically or we secure a major new source of revenue, we're living on borrowed time, and it's only going to get worse." He smiled without humor. "It's a pity most of the systems we've acquired weren't in much better economic shape than we were."

"And you're certain we can't reduce Fleet expenditures, Elaine?"

"Not without running very grave risks, Mr. President. Admiral Parnell is perfectly correct about how our neighbors will react if we waver." It was her turn to smile grimly. "I suppose we've taught them too well."

"Maybe we have," Parnell said, "but there's an answer to that." Eyes turned to him, and he shrugged. "Knock them off now. If we take out the remaining military powers on our frontiers, we can probably cut back to something more like a peace-keeping posture of our own."

"Jesus, Admiral!" Bergren snorted. "First you tell us we can't hold what we've got without spending ourselves into exhaustion, and now you want to kick off a whole new series of wars? Talk about the mysteries of the military mind—!"

"Hold on a minute, Ron," Harris murmured. He cocked his head at the admiral. "Could you pull it off, Amos?"

"I believe so," Parnell replied more cautiously. "The problem would be timing." He touched a button and a holo map glowed to life above the table. The swollen sphere of the People's Republic crowded its northeastern quadrant, and he gestured at a rash of amber and red star systems to the south and west. "There are no multi-system powers closer than the Anderman Empire," he pointed out. "Most of the single-system governments are strictly small change; we could blow out any one of them with a single task force, despite their armament programs. What makes them dangerous is the probability that they'll get organized as a unit if we give them time."

Harris nodded thoughtfully, but reached out and touched one of the beads of light that glowed a dangerous blood-red. "And Manticore?" he asked.

"That's the joker in the deck," Parnell agreed. "They're big enough to give us a fight, assuming they've got the guts for it."

"So why not avoid them, or at least leave them for last?" Bergren asked. "Their domestic parties are badly divided over what to do about us—couldn't we chop up the other small fry first?"

"We'd be in worse shape if we did," Frankel objected. He touched a button of his own, and two-thirds of the amber lights on Parnell's map turned a sickly gray-green. "Each of those systems is almost as far in the hole economically as we are," he pointed out. "They'll actually cost us money to take over, and the others are barely break-even propositions. The systems we really need are further south, down towards the Erewhon Junction, or over in the Silesian Confederacy to the west."

"Then why not grab them straight off?" Harris asked.

"Because Erewhon has virtual League membership, Mr. President," Dumarest replied, "and going south might convince the League we're threatening its territory. That could be, ah, a bad idea." Heads nodded around the table. The Solarian League had the wealthiest, most powerful economy in the known galaxy, but its foreign and military policies were the product of so many compromises that they virtually did not exist, and no one in this room wanted to irritate the sleeping giant into evolving ones that did.

"So we can't go south," Dumarest went on, "but going west instead brings us right back to Manticore."

"Why?" Frankel asked. "We could take Silesia without ever coming within a hundred light-years of Manticore—

just cut across above them and leave them alone."

"Oh?" Parnell challenged. "And what about the Manticore Wormhole Junction? Its Basilisk terminus would be right in our path. We'd almost have to take it just to protect our flank, and even if we didn't, the Royal Manticoran Navy would see the implications once we started expanding around their northern frontier. They'd have no choice but to try to stop us."

"We couldn't cut a deal with them?" Frankel asked Bergren, and the foreign secretary shrugged.

"The Manticoran Liberal Party can't find its ass with both hands where foreign policy is concerned, and the Progressives would probably dicker, but they aren't in control; the Centrists and Crown Loyalists are. They hate our guts, and Elizabeth III hates us even more than they do. Even if the Liberals and Progressives could turn the Government out, the Crown would never negotiate with us."

"Um." Frankel plucked at his lip, then sighed. "Too bad, because there's another point. We're in bad enough shape for foreign exchange, and three-quarters of our foreign trade moves through the Manticore Junction. If they close it against us, it'll add months to transit times . . . and costs."

"Tell me about it," Parnell said sourly. "That damned junction also gives their navy an avenue right into the middle of the Republic through the Trevor's Star terminus."

"But if we knocked them out, then we'd hold the Junction," Dumarest murmured. "Think what that would do for our economy."

Frankel looked up, eyes glowing with sudden avarice, for the junction gave the Kingdom of Manticore a gross system product seventy-eight percent that of the Sol System itself. Harris noted his expression and gave a small, ugly smile.

"All right, let's look at it. We're in trouble and we know it. We have to keep expanding. Manticore is in the way, and taking it would give our economy a hefty shot in the arm. The problem is what we do about it."

"Manticore or not," Parnell said thoughtfully, "we have to pinch out these problem spots to the southwest." He gestured at the systems Frankel had dyed gray-green. "It'd be a worthwhile preliminary to position us against Manticore, anyway. But if we can do it, the smart move would be to take out Manticore first and then deal with the small fry."

"Agreed," Harris nodded. "Any ideas on how we might do that?"

"Let me get with my staff, Mr. President. I'm not sure yet, but the Junction could be a two-edged sword if we handle it right. . . ." The admiral's voice trailed off, then he shook himself. "Let me get with my staff," he repeated. "Especially with Naval Intelligence. I've got an idea, but I need to work on it." He cocked his head. "I can probably have a report, one way or the other, for you in about a month. Will that be acceptable?"

"Entirely, Admiral," Harris said, and adjourned the meeting.

CHAPTER ONE

The fluffy ball of fur in Honor Harrington's lap stirred and put forth a round, prick-eared head as the steady pulse of the shuttle's thrusters died. A delicate mouth of needle-sharp fangs yawned, and then the treecat turned its head to regard her with wide, grass-green eyes.

"Bleek?" it asked, and Honor chuckled softly.

"'Bleek' yourself," she said, rubbing the ridge of its muzzle. The green eyes blinked, and four of the treecat's six limbs reached out to grip her wrist in feather-gentle hand-paws. She chuckled again, pulling back to initiate a playful tussle, and the treecat uncoiled to its full sixty-five centimeters (discounting its tail) and buried its true-feet in her midriff with the deep, buzzing hum of its purr. The hand-paws tightened their grip, but the murderous claws—a full centimeter of curved, knife-sharp ivory—were sheathed. Honor had once seen similar claws used to rip apart the face of a human foolish enough to threaten a treecat's companion, but she felt no concern. Except in self-defense (or Honor's defense) Nimitz would no more hurt a human being than turn vegetarian, and treecats never made mistakes in that respect.

She extricated herself from Nimitz's grasp and lifted the long, sinuous creature to her shoulder, a move he greeted with even more enthusiastic purrs. Nimitz was an old hand at space travel and understood shoulders were out of bounds aboard small craft under power, but he also knew treecats belonged on their companions' shoulders. That was where they'd ridden since the first 'cat adopted its first human five Terran centuries before, and Nimitz was a traditionalist.

A flat, furry jaw pressed against the top of her head as Nimitz sank his four lower sets of claws into the specially padded shoulder of her uniform tunic. Despite his long, narrow body, he was a hefty weight—almost nine kilos—even under the shuttle's single gravity, but Honor was used to it, and Nimitz had learned to move his center of balance in from the point of her shoulder. Now he clung effortlessly to his perch while she collected her briefcase from the empty seat beside her. Honor was the half-filled shuttle's senior passenger, which had given her the seat just inside the hatch. It was a practical as well as a courteous tradition, since the senior officer was always last to board and first to exit.

The shuttle quivered gently as its tractors reached out to the seventy-kilometer bulk of Her Majesty's Space Station Hephaestus, the Royal Manticoran Navy's premiere shipyard, and Nimitz sighed his relief into Honor's short-cropped mass of feathery, dark brown hair. She smothered another grin and rose from her bucket seat to twitch her tunic straight. The shoulder seam had dipped under Nimitz's weight, and it took her a moment to get the red-and-gold navy shoulder flash with its roaring, lion-headed, bat-winged manticore, spiked tail poised to strike, back where it belonged. Then she plucked the beret from under her left epaulet. It was the special beret, the white one she'd bought when they gave her Hawkwing, and she chivied Nimitz's jaw gently aside and settled it on her head. The treecat put up with her until she had it adjusted just so, then shoved his chin back into its soft warmth, and she felt her face crease in a huge grin as she turned to the hatch.

That grin was a violation of her normally severe "professional expression," but she was entitled. Indeed, she felt more than mildly virtuous for holding herself to a grin when what she really wanted to do was spin on her toes, fling her arms wide, and carol her delight to her no-doubt shocked fellow passengers. But she was almost twenty-four years old—over forty Terran standard years—and it would never, never have done for a commander of the Royal Manticoran Navy to be so undignified, even if she was about to assume command of her first cruiser.

She smothered another chuckle, luxuriating in the unusual sense of complete and simple joy, and pressed a hand to the front of her tunic. The folded sheaf of archaic paper crackled at her touch—a curiously sensual, exciting sound—and she closed her eyes to savor it even as she savored the moment she'd worked so hard to reach.

Fifteen years—twenty-five T-years—since that first exciting, terrifying day on the Saganami campus. Two and a half years of Academy classes and running till she dropped. Four years working her way without patronage or court interest from ensign to lieutenant. Eleven months as sailing master aboard the frigate Osprey, and then her first command, a dinky little intrasystem LAC. It had massed barely ten thousand tons, with only a hull number and not even the dignity of a name, but God how she'd loved that tiny ship! Then more time as executive officer, a turn as tactical officer on a massive superdreadnought. And then—finally!—the coveted commanding officer's course after eleven grueling years. She'd thought she'd died and gone to heaven when they gave her Hawkwing, for the middle-aged destroyer had been her very first hyper-capable command, and the thirty-three months she'd spent in command had been pure, unalloyed joy, capped by the coveted Fleet "E" award for tactics in last year's war games. But this—!

The deck shuddered beneath her feet, and the light above the hatch blinked amber as the shuttle settled into Hephaestus's docking buffers, then burned a steady green as pressure equalized in the boarding tube. The panel slid aside, and Honor stepped briskly through it.

The shipyard tech manning the hatch at the far end of the tube saw the white beret of a starship's captain and the three gold stripes of a full commander on a space-black sleeve and

came to attention, but his snappy response was flawed by a tiny hesitation as he caught sight of Nimitz. He flushed and twitched his eyes away, but Honor was used to that reaction. The treecats native to her home world of Sphinx were picky about which humans they adopted. Relatively few were seen off-world, but they refused to be parted from their humans even if those humans chose space-going careers, and the Lords of Admiralty had caved in on that point almost a hundred and fifty Manticoran years before. 'Cats rated a point-eight-three on the sentience scale, slightly above Beowulf's gremlins or Old Earth's dolphins, and they were empaths. Even now, no one had the least idea how their empathic links worked, but separating one from its chosen companion caused it intense pain, and it had been established early on that those favored by a 'cat were measurably more stable than those without. Besides, Crown Princess Adrienne had been adopted by a 'cat on a state visit to Sphinx. When Queen Adrienne of Manticore expressed her displeasure twelve years later at efforts to separate officers in her navy from their companions, the Admiralty found itself with no option but to grant a special exemption from its draconian "no pets" policy.

Honor was glad of it, though she'd been afraid it would be impossible to find time to spend with Nimitz when she entered the Academy. She'd known going in that those forty-five endless months on Saganami Island were deliberately planned to leave even midshipmen without 'cats too few hours to do everything they had to do. But while Academy instructors might suck their teeth and grumble when a plebe turned up with one of the rare 'cats, they recognized natural forces for which allowances must be made when they saw one. Besides, even the most "domesticated" 'cat retained the independence (and indestructibility) of his cousins in the wild, and Nimitz had seemed perfectly aware of the pressure she faced. All he needed was a little grooming, an occasional wrestling bout, a perch on her shoulder or lap while she pored over the book chips and to sleep curled neatly up on her pillow, and he was happy. Not that he'd been above looking mournful and pitiful to extort tidbits and petting from any unfortunate who crossed his path. Even Chief MacDougal, the terror of the first-form middies, had succumbed, carrying a suitable stash of the celery stalks the otherwise carnivorous treecats craved and sneaking them to Nimitz when he thought no one was looking. And, Honor reflected wryly, running Ms. Midshipman Harrington ragged to compensate for his weakness.